List of climate change controversies: Difference between revisions

→Funding: moved |

→Litigation: moved to climate change litigation |

||

| Line 854: | Line 854: | ||

}} |

}} |

||

</ref> UVA filed a court petition and the judge dismissed Cuccinelli's demand on the grounds that no justification had been shown for the investigation.<ref name="ucsusa.org">{{cite web| url = http://www.ucsusa.org/news/press_release/judge-dismisses-ken-cuccinelli-mann-0437.html| title = Judge Dismisses Ken Cuccinelli's Misguided Investigation of Michael Mann {{!}} Union of Concerned Scientists<!-- Bot generated title -->| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100902015145/http://www.ucsusa.org/news/press_release/judge-dismisses-ken-cuccinelli-mann-0437.html| archive-date = 2 September 2010}}</ref> Cuccinelli then issued a revised subpoena, and appealed the case to the Virginia Supreme Court which ruled in March 2012 that Cuccinelli did not have the authority to make these demands. The outcome was hailed as a victory for academic freedom.<ref name="Wapo 020312">{{Cite news | last = Kumar | first = Anita | title = Va. Supreme Court tosses Cuccinelli's case against former U-Va. climate change researcher – Virginia Politics | url = https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/virginia-politics/post/va-supreme-court-tosses-cuccinellis-case-against-u-va/2012/03/02/gIQAeOqjmR_blog.html | publisher = The Washington Post blogs | date = 2 March 2012 | access-date = 2 March 2012 }}</ref><ref name="Graun 020312">{{Cite news | last = Goldenberg | first = Suzanne | title = Virginia court rejects sceptic's bid for climate science emails : Environment | url = https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/mar/02/virginia-court-sceptic-access-climate-emails | newspaper = The Guardian | date = 2 March 2012 | access-date = 2 March 2012 | location=London}}</ref> |

</ref> UVA filed a court petition and the judge dismissed Cuccinelli's demand on the grounds that no justification had been shown for the investigation.<ref name="ucsusa.org">{{cite web| url = http://www.ucsusa.org/news/press_release/judge-dismisses-ken-cuccinelli-mann-0437.html| title = Judge Dismisses Ken Cuccinelli's Misguided Investigation of Michael Mann {{!}} Union of Concerned Scientists<!-- Bot generated title -->| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20100902015145/http://www.ucsusa.org/news/press_release/judge-dismisses-ken-cuccinelli-mann-0437.html| archive-date = 2 September 2010}}</ref> Cuccinelli then issued a revised subpoena, and appealed the case to the Virginia Supreme Court which ruled in March 2012 that Cuccinelli did not have the authority to make these demands. The outcome was hailed as a victory for academic freedom.<ref name="Wapo 020312">{{Cite news | last = Kumar | first = Anita | title = Va. Supreme Court tosses Cuccinelli's case against former U-Va. climate change researcher – Virginia Politics | url = https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/virginia-politics/post/va-supreme-court-tosses-cuccinellis-case-against-u-va/2012/03/02/gIQAeOqjmR_blog.html | publisher = The Washington Post blogs | date = 2 March 2012 | access-date = 2 March 2012 }}</ref><ref name="Graun 020312">{{Cite news | last = Goldenberg | first = Suzanne | title = Virginia court rejects sceptic's bid for climate science emails : Environment | url = https://www.theguardian.com/environment/2012/mar/02/virginia-court-sceptic-access-climate-emails | newspaper = The Guardian | date = 2 March 2012 | access-date = 2 March 2012 | location=London}}</ref> |

||

=== Litigation === |

|||

Several lawsuits have been filed over global warming. For example, ''[[Massachusetts v. Environmental Protection Agency]]'' before the [[Supreme Court of the United States]] allowed the [[United States Environmental Protection Agency|EPA]] to [[Regulation of greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act|regulate greenhouse gases under the Clean Air Act]]. A similar approach was taken by California Attorney General [[Bill Lockyer]] who filed a lawsuit ''[[California v. General Motors Corp.]]'' to force car manufacturers to reduce vehicles' emissions of carbon dioxide. This lawsuit was found to lack legal merit and was tossed out.<ref>{{cite news |last=Lifsher |first=Marc |newspaper=Los Angeles Times |title=Global warming lawsuit dismissed |url=https://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/18/business/fi-warmsuit18 |url-status=live |archive-date=4 October 2009 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20091004161743/http://articles.latimes.com/2007/sep/18/business/fi-warmsuit18 |date=18 September 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite news |last=Tanner |first=Adam |work=Reuters |title=Calif. suit on car greenhouse gases dismissed |url=https://www.reuters.com/article/us-california-autos-idUSN1736580020070918 |url-status=live |archive-date=15 February 2013 |archive-url=https://web.archive.org/web/20130215065243/https://www.reuters.com/article/2007/09/18/us-california-autos-idUSN1736580020070918 |date=18 September 2007}}</ref> A third case, ''[[Comer v. Murphy Oil USA, Inc.]]'', a class action lawsuit filed by Gerald Maples, a trial attorney in Mississippi, in an effort to force fossil fuel and chemical companies to pay for damages caused by global warming. Described as a [[Frivolous litigation|nuisance lawsuit]], it was dismissed by District Court.<ref>{{cite web|first=Justin R.|last=Pidot|publisher=[[Georgetown University Law Center]]|year=2006|url=http://www.law.stanford.edu/program/centers/enrlp/pdf/GlobalWarmingLit_CourtsReport.pdf|title=Global Warming in the Courts – An Overview of Current Litigation and Common Legal Issues|access-date=13 April 2007| archive-url = https://web.archive.org/web/20070604183808/http://www.law.stanford.edu/program/centers/enrlp/pdf/GlobalWarmingLit_CourtsReport.pdf| archive-date = 4 June 2007}}</ref> However, the District Court's decision was overturned by the [[United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit]], which instructed the District Court to reinstate several of the plaintiffs' climate change-related claims on 22 October 2009.<ref>http://www.ca5.uscourts.gov/opinions/pub/07/07-60756-CV0.wpd.pdf {{full citation needed|date=November 2012}}</ref> The [[Sierra Club]] sued the U.S. government over failure to raise [[Fuel economy in automobiles|automobile fuel efficiency standards]], and thereby decrease carbon dioxide emissions.<ref>{{cite web|title=Proposed Settlement Agreement, Clean Air Act Citizen Suit|url=http://www.epa.gov/fedrgstr/EPA-AIR/2005/August/Day-12/a16037.htm|publisher=[[United States Environmental Protection Agency]]|date=12 August 2005|access-date=13 April 2007}}</ref><ref>{{cite court|litigants=The [[Sierra Club]] vs. [[Stephen L. Johnson]] ([[United States Environmental Protection Agency]])|court=[[United States Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit]]|date=20 January 2006|opinion=03-10262|url=http://www.ca11.uscourts.gov/opinions/ops/200310262.pdf|access-date=13 April 2007}}</ref> |

|||

==== ''Kelsey Cascade, Rose Juliana et. al. vs. United States'' ==== |

|||

In a lawsuit organized by activist organization Our Children's Trust, a group of plaintiffs aged 8–19 sued the U. S. Federal Government, claiming "the government has known for decades that carbon dioxide ({{CO2}}) pollution has been causing catastrophic climate change and has failed to take necessary action to curtail fossil fuel emissions." On 8 April 2016, U.S. Magistrate Judge Thomas Coffin denied defendant's motion to dismiss, arguing plaintiffs have standing to sue because they will be disproportionately affected by the alleged damages. "The intractability of the debates before Congress and state legislatures and the alleged valuing of short term economic interest despite the cost to human life," argued Coffin, "necessitates a need for the courts to evaluate the constitutional parameters of the action or inaction taken by the government".<ref>{{cite web| url = http://ourchildrenstrust.org/sites/default/files/16.04.08.OrderDenyingMTD.pdf| title = Findings and Recommendation 6:15-cv-1517-TC}}</ref> |

|||

== See also == |

== See also == |

||

Revision as of 23:29, 8 November 2023

It has been suggested that this article be merged into History of climate change policy and politics. (Discuss) Proposed since November 2023. |

This article needs to be updated. The reason given is: much of this content discusses the controversy from 20 years ago with sources from that time. It needs the inclusion of more recent retrospectives and subsequent context. (September 2022) |

| Part of a series on |

| Climate change and society |

|---|

The global warming controversy concerns the public debate over whether global warming is occurring, how much has occurred in modern times, what has caused it, what its effects will be, whether any action can or should be taken to curb it, and if so what that action should be. In the scientific literature, there is a very strong consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.[1][2][3][4][5][6] No scientific body of national or international standing disagrees with this view,[7] though a few organizations with members in extractive industries hold non-committal positions,[8] and some have tried to persuade the public that climate change is not happening, or if the climate is changing it is not because of human influence,[9][10] attempting to sow doubt in the scientific consensus.[11]

As of 2022[update] the U.S. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration says the global yearly average temperature has been warming at rate of 0.18 °C (0.32 °F) per decade since 1981.[12]

The controversy is, by now, political rather than scientific: there is a scientific consensus that global warming is happening and is caused by human activity.[13] Disputes over the key scientific facts of global warming are more prevalent in the media than in the scientific literature, where such issues are treated as resolved, and such disputes are more prevalent in the United States and Australia than globally.[9][14][15]

Political and popular debate concerning the existence and cause of global warming includes the reasons for the increase seen in the instrumental temperature record, whether the warming trend exceeds normal climatic variations, and whether human activities have contributed significantly to it. Scientists have answered these questions decisively in favor of the view that the current warming trend exists and is ongoing, that human activity is the cause, and that it is without precedent in at least 2000 years.[16] Public disputes that also reflect scientific debate include estimates of how responsive the climate system might be to any given level of greenhouse gases (climate sensitivity), how the climate will change at local and regional scales, and what the consequences of global warming will be.

Global warming remains an issue of widespread political debate, often split along party political lines, especially in the United States.[17] Many of the issues that are settled within the scientific community, such as human responsibility for global warming, remain the subject of politically or economically motivated attempts to downplay, dismiss or deny them—an ideological phenomenon categorized by academics and scientists as climate change denial. The sources of funding for those involved with climate science opposing mainstream scientific positions have been questioned. There are debates about the best policy responses to the science, their cost-effectiveness and their urgency. Climate scientists, especially in the United States, have reported government and oil-industry pressure to censor or suppress their work and hide scientific data, with directives not to discuss the subject in public communications. Legal cases regarding global warming, its effects, and measures to reduce it have reached American courts. The fossil fuels lobby has been identified as overtly or covertly supporting efforts to undermine or discredit the scientific consensus on global warming.[9][18]

History

Public opinion

The theory that increases in greenhouse gases would lead to an increase in temperature was first proposed by the Swedish chemist Svante Arrhenius in 1896, but climate change did not arise as a political issue until the 1990s. It took many years for this particular issue to attract any type of popular attention.[27]

In the United States, the mass media devoted little coverage to global warming until the drought of 1988, and James E. Hansen's testimony to the Senate, which explicitly attributed "the abnormally hot weather plaguing our nation" to global warming. Global warming in the U.S. gained more attention after the release of the 2006 documentary An Inconvenient Truth, featuring Al Gore.[28]

The British press also changed its coverage at the end of 1988, following a speech by Margaret Thatcher to the Royal Society advocating action against human-induced climate change.[29] According to Anabela Carvalho, an academic analyst, Thatcher's "appropriation" of the risks of climate change to promote nuclear power, in the context of the dismantling of the coal industry following the 1984–1985 miners' strike was one reason for the change in public discourse. At the same time environmental organizations and the political opposition were demanding "solutions that contrasted with the government's".[30] In May 2013 Charles, Prince of Wales took a strong stance criticising both climate change deniers and corporate lobbyists by likening the Earth to a dying patient. "A scientific hypothesis is tested to absolute destruction, but medicine can't wait. If a doctor sees a child with a fever, he can't wait for [endless] tests. He has to act on what is there."[31]

Many European countries took action to reduce greenhouse gas emissions before 1990. West Germany started to take action after the Green Party took seats in Parliament in the 1980s. All countries of the European Union ratified the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. Substantial activity by NGOs took place as well.[32] The United States Energy Information Administration reports that, in the United States, "The 2012 downturn means that emissions are at their lowest level since 1994 and over 12% below the recent 2007 peak."[33]

In Europe, the notion of human influence on climate gained wide acceptance more rapidly than in the United States and other countries.[34][35] A 2009 survey found that Europeans rated climate change as the second most serious problem facing the world, between "poverty, the lack of food and drinking water" and "a major global economic downturn". 87% of Europeans considered climate change to be a very serious or serious problem, while ten per cent did not consider it a serious problem.[36]

In 2007, the BBC announced the cancellation of a planned television special Planet Relief, which would have highlighted the global warming issue and included a mass electrical switch-off.[37] The editor of BBC's Newsnight current affairs show said: "It is absolutely not the BBC's job to save the planet. I think there are a lot of people who think that, but it must be stopped."[38] Author Mark Lynas said "The only reason why this became an issue is that there is a small but vociferous group of extreme right-wing climate 'sceptics' lobbying against taking action, so the BBC is behaving like a coward and refusing to take a more consistent stance."[39]

The authors of the 2010 book Merchants of Doubt, provide documentation for the assertion that professional deniers have tried to sow seeds of doubt in public opinion in order to halt any meaningful social or political progress to reduce the impact of human carbon emissions. The fact that only half of the American population believes global warming is caused by human activity could be seen as a victory for these deniers.[15] One of the authors' main arguments is that most prominent scientists who have been voicing opposition to the near-universal consensus are being funded by industries, such as automotive and oil, that stand to lose money by government actions to regulate greenhouse gases.[40]

A compendium of poll results on public perceptions about global warming is below.[41][42][43]

| Statement | % agree | Year |

|---|---|---|

| (US) Global Warming is very/extremely important[42] | 49 | 2006 |

| (International) Climate change is a serious problem.[44] | 90 | 2006 |

| (International) Human activity is a significant cause of climate change.[43] | 79 | 2007 |

| (US) It's necessary to take major steps starting very soon.[43] | 59 | 2007 |

| (US) The Earth is getting warmer because of human activity[45] | 49 | 2009 |

In 2007, a report on public perceptions in the United Kingdom by Ipsos MORI[46] reported that:

- There is widespread recognition that the climate, irrespective of the cause, is changing—88% believe this to be true.

- However, the public is out of step with the scientific community, with 41% believing that climate change is being caused by both human activity and natural processes. 46% believe human activity is the main cause.

- Only a small minority reject anthropogenic climate change, while almost half (44%) are very concerned. However, there remains a large proportion who are not fully persuaded and hold doubts about the extent of the threat.

- There is still a strong appetite among the public for more information, and 63% say they need this to come to a firm view on the issue and what it means for them.

- The public continue to externalize climate change to other people, places and times. It is increasingly perceived as a major global issue with far-reaching consequences for future generations—45% say it is the most serious threat facing the World today and 53% believe it will impact significantly on future generations. However, the issue features less prominently nationally and locally, indeed only 9% believe climate change will have a significant impact upon them personally.

The Canadian science broadcaster and environmental activist David Suzuki reports that focus groups organized by the David Suzuki Foundation in 2006 showed that the public has a poor understanding of the science behind global warming.[48] This is despite publicity through different means, including the films An Inconvenient Truth and The 11th Hour.[49][50]

An example of the poor understanding is public confusion between global warming and ozone depletion or other environmental problems.[51][52]

A 15-nation poll conducted in 2006, by Pew Global found that there "is a substantial gap in concern over global warming—roughly two-thirds of Japanese (66%) and Indians (65%) say they personally worry a great deal about global warming. Roughly half of the populations of Spain (51%) and France (46%) also express great concern over global warming, based on those who have heard about the issue. But there is no evidence of alarm over global warming in either the United States or China—the two largest producers of greenhouse gases. Just 19% of Americans and 20% of the Chinese who have heard of the issue say they worry a lot about global warming—the lowest percentages in the 15 countries surveyed. Moreover, nearly half of Americans (47%) and somewhat fewer Chinese (37%) express little or no concern about the problem."[53]

A 47-nation poll by Pew Global Attitudes conducted in 2007, found, "Substantial majorities 25 of 37 countries say global warming is a 'very serious' problem."[54]

There are differences between the opinion of scientists and that of the general public.[55][56] A 2009 poll, in the US by Pew Research Center found "[w]hile 84% of scientists say the earth is getting warmer because of human activity such as burning fossil fuels, just 49% of the public agrees".[45] A 2010 poll in the UK for the BBC showed "Climate scepticism on the rise".[57] Robert Watson found this "very disappointing" and said "We need the public to understand that climate change is serious so they will change their habits and help us move towards a low carbon economy."[57] A 2012 Canadian poll, found that 32% of Canadians said they believe climate change is happening because of human activity, while 54% said they believe it's because of human activity and partially due to natural climate variation. 9% believe climate change is occurring due to natural climate variation, and only 2% said they do not believe climate change is occurring at all.[58]

Related controversies

Many of the critics of the consensus view on global warming have disagreed, in whole or part, with the scientific consensus regarding other issues, particularly those relating to environmental risks, such as ozone depletion, DDT, and passive smoking.[59][60] Chris Mooney, author of The Republican War on Science, has argued that the appearance of overlapping groups of "skeptical" scientists, commentators and think tanks in seemingly unrelated controversies results from an organized attempt to replace scientific analysis with political ideology. Mooney says that the promotion of doubt regarding issues that are politically, but not scientifically, controversial became increasingly prevalent under the George W. Bush administration, which, he says, regularly distorted and/or suppressed scientific research to further its own political aims. This is also the subject of a 2004 book by environmental lawyer Robert F. Kennedy, Jr. titled Crimes Against Nature: How George W. Bush and Corporate Pals are Plundering the Country and Hijacking Our Democracy (ISBN 978-0060746872). Another book on this topic is The Assault on Reason by former Vice President of the United States Al Gore. The Heat Is On by Ross Gelbspan chronicles how Congress tied climate change denial to attacks on the scientific bases for ozone depletion and asbestos removal, among other topics.[61]

Some critics of the scientific consensus on global warming have argued that these issues should not be linked and that reference to them constitutes an unjustified ad hominem attack.[62] Political scientist Roger Pielke, Jr., responding to Mooney, has argued that science is inevitably intertwined with politics.[63]

In 2015, according to The New York Times and others, oil companies knew that burning oil and gas could cause global warming since the 1970s but, nonetheless, funded deniers for years.[64][65]

Scientific consensus

There is a nearly unanimous scientific consensus that the Earth has been consistently warming since the start of the Industrial Revolution, that the rate of recent warming is largely unprecedented,[66]: 8 [67]: 11 and that this warming is mainly the result of a rapid increase in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) caused by human activities. The human activities causing this warming include fossil fuel combustion, cement production, and land use changes such as deforestation,[68]: 10–11 with a significant supporting role from the other greenhouse gases such as methane and nitrous oxide.[66]: 7 This human role in climate change is considered "unequivocal" and "incontrovertible".[66]: 4 [67]: 4

Nearly all actively publishing climate scientists say humans are causing climate change.[69][70] Surveys of the scientific literature are another way to measure scientific consensus. A 2019 review of scientific papers found the consensus on the cause of climate change to be at 100%,[71] and a 2021 study concluded that over 99% of scientific papers agree on the human cause of climate change.[72] The small percentage of papers that disagreed with the consensus often contained errors or could not be replicated.[73]

The evidence for global warming due to human influence has been recognized by the national science academies of all the major industrialized countries.[74] In the scientific literature, there is a very strong consensus that global surface temperatures have increased in recent decades and that the trend is caused by human-induced emissions of greenhouse gases.[75] No scientific body of national or international standing disagrees with this view.[76] A few organizations with members in extractive industries hold non-committal positions,[77] and some have tried to persuade the public that climate change is not happening, or if the climate is changing it is not because of human influence,[78][79] attempting to sow doubt in the scientific consensus.[80]

Lines of argument by those who disagree with the scientific consensus

Among opponents of the mainstream scientific assessment, some say that while there is agreement that humans do have an effect on climate, there is no universal agreement about the quantitative magnitude of anthropogenic global warming (AGW) relative to natural forcings and its harm-to-benefit ratio.[82] Other opponents assert that some kind of ill-defined "consensus argument" is being used, and then dismiss this by arguing that science is based on facts rather than consensus.[83] Some highlight the dangers of focusing on only one viewpoint in the context of what they say is unsettled science, or point out that science is based on facts and not on opinion polls or consensus.[84][85]

Dennis T. Avery, a food policy analyst at the Hudson Institute, wrote an article titled "500 Scientists Whose Research Contradicts Man-Made Global Warming Scares"[86] published in 2007, by the Heartland Institute. The list was immediately called into question for misunderstanding and distorting the conclusions of many of the named studies and citing outdated, flawed studies that had long been abandoned. Many of the scientists included in the list demanded their names be removed.[87][88] At least 45 scientists had no idea they were included as "co-authors" and disagreed with the conclusions of the document.[89] The Heartland Institute refused these requests, stating that the scientists "have no right—legally or ethically—to demand that their names be removed from a bibliography composed by researchers with whom they disagree".[89]

A 2010 paper in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences analyzed "1,372 climate researchers and their publication and citation data to show that (i) 97–98% of the climate researchers most actively publishing in the field support the tenets of ACC [anthropogenic climate change] outlined by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, and (ii) the relative climate expertise and scientific prominence of the researchers unconvinced of ACC are substantially below that of the convinced researchers".[90][91] Judith Curry has said "This is a completely unconvincing analysis", whereas Naomi Oreskes said that the paper shows "the vast majority of working [climate] research scientists are in agreement [on climate change]... Those who don't agree, are, unfortunately—and this is hard to say without sounding elitist—mostly either not actually climate researchers or not very productive researchers."[91][92] Jim Prall, one of the coauthors of the study, acknowledged "it would be helpful to have lukewarm [as] a third category."[91]

A 2013 study, published in the peer-reviewed journal Environmental Research Letters analyzed 11,944 abstracts from papers published in the peer-reviewed scientific literature between 1991 and 2011, identified by searching the ISI Web of Science citation index engine for the text strings "global climate change" or "global warming". The authors found that 3974 of the abstracts expressed a position on anthropogenic global warming, and that 97% of those endorsed the consensus that humans are causing global warming. The authors found that of the 11,944 abstracts, 3896 endorsed that consensus, 7930 took no position on it, 78 rejected the consensus, and 40 expressed uncertainties about it.[93]

Authority of the IPCC

The "standard" view of climate change has come to be defined by the reports of the IPCC, which is supported by many other science academies and scientific organizations. In 2001, sixteen of the world's national science academies made a joint statement on climate change and gave their support for the IPCC.[94]

Opponents have generally attacked either the IPCC's processes, people[95] or the Synthesis and Executive summaries; the full reports attract less attention. Some of the controversy and criticism has originated from experts invited by the IPCC to submit reports or serve on its panels.

Christopher Landsea, a hurricane researcher, said of "the part of the IPCC to which my expertise is relevant" that "I personally cannot in good faith continue to contribute to a process that I view as both being motivated by pre-conceived agendas and being scientifically unsound,"[96] because of comments made at a press conference by Kevin Trenberth of which Landsea disapproved. Trenberth said "Landsea's comments were not correct";[97] the IPCC replied "individual scientists can do what they wish in their own rights, as long as they are not saying anything on behalf of the IPCC" and offered to include Landsea in the review phase of the AR4.[98] Roger Pielke, Jr. commented "Both Landsea and Trenberth can and should feel vindicated ... the IPCC accurately reported the state of scientific understandings of tropical cyclones and climate change in its recent summary for policy makers."[97]

In 2005, the House of Lords Economics Committee wrote, "We have some concerns about the objectivity of the IPCC process, with some of its emissions scenarios and summary documentation apparently influenced by political considerations." It doubted the high emission scenarios and said that the IPCC had "played-down" what the committee called "some positive aspects of global warming".[99] The main statements of the House of Lords Economics Committee were rejected in the response made by the United Kingdom government.[100]

Speaking to the difficulty of establishing scientific consensus on the precise extent of human action on climate change, John Christy, a contributing author, wrote:

Contributing authors essentially are asked to contribute a little text at the beginning and to review the first two drafts. We have no control over editing decisions. Even less influence is granted the 2,000 or so reviewers. Thus, to say that 800 contributing authors or 2,000 reviewers reached consensus on anything describes a situation that is not reality.[101]

On 10 December 2008, a report was released by the U.S. Senate Committee on Environment and Public Works Minority members, under the leadership of the Senate's most vocal global warming denier Jim Inhofe. The timing of the report coincided with the UN global warming conference in Poznań, Poland. It says it summarizes scientific dissent from the IPCC.[102] Many of its statements about the numbers of individuals listed in the report, whether they are actually scientists, and whether they support the positions attributed to them, have been disputed.[103][104][105]

While some critics have argued that the IPCC overstates likely global warming, others have made the opposite criticism. David Biello, writing in the Scientific American, argues that, because of the need to secure consensus among governmental representatives, the IPCC reports give conservative estimates of the likely extent and effects of global warming.[106] Science editor Brooks Hanson states in a 2010 editorial: "The IPCC reports have underestimated the pace of climate change while overestimating societies' abilities to curb greenhouse gas emissions."[107] Climate scientist James E. Hansen argues that the IPCC's conservativeness seriously underestimates the risk of sea-level rise on the order of meters—enough to inundate many low-lying areas, such as the southern third of Florida.[108] Roger A. Pielke Sr. has also stated "Humans are significantly altering the global climate, but in a variety of diverse ways beyond the radiative effect of carbon dioxide. The IPCC assessments have been too conservative in recognizing the importance of these human climate forcings as they alter regional and global climate."[109]

Greenhouse gases

One argument brought forward against the existence of global warming says that rising levels of carbon dioxide (CO2) and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) do not correlate with global warming.[110] For example, studies of the Vostok ice core show that at the "beginning of the deglaciations, the CO2 increase either was in phase or lagged by less than ~1000 years with respect to the Antarctic temperature, whereas it clearly lagged behind the temperature at the onset of the glaciations".[111] Recent warming is followed by carbon dioxide levels with only a five-month delay.[112] The time lag has been used to argue that the current rise in CO2 is a result of warming and not a cause.

While it is generally agreed that variations before the industrial age are mostly timed by astronomical forcing,[113] a main part of current warming is found to be timed by anthropogenic releases of CO2, having a much closer time relation not observed in the past (thus returning the argument to the importance of human CO2 emissions). Analysis of carbon isotopes in atmospheric CO2 shows that the recent observed CO2 increase cannot have come from the oceans, volcanoes, or the biosphere, and thus is not a response to rising temperatures as would be required if the same processes creating past lags were active now.[114]

Solar variation

The consensus position is that solar radiation may have increased by 0.12 W/m2 since 1750, compared to 1.6 W/m2 for the net anthropogenic forcing.[115] The IPCC Third Assessment Report found that, "The combined change in radiative forcing of the two major natural factors (solar variation and volcanic aerosols) is estimated to be negative for the past two, and possibly the past four, decades."[116]

A few studies say that the present level of solar activity is historically high as determined by sunspot activity and other factors. Solar activity could affect climate either by variation in the Sun's output or, more speculatively, by an indirect effect on the amount of cloud formation. Solanki and co-workers suggest that solar activity for the last 60 to 70 years may be at its highest level in 8,000 years, however they said "that solar variability is unlikely to have been the dominant cause of the strong warming during the past three decades", and concluded that "at the most 30% of the strong warming since [1970] can be of solar origin".[117] Muscheler et al. disagreed with the study, suggesting that other comparably high levels of activity have occurred several times in the last few thousand years.[118] They concluded that "solar activity reconstructions tell us that only a minor fraction of the recent global warming can be explained by the variable Sun."[119]

Another point of controversy is the correlation of temperature with solar variation.[120]

Mike Lockwood and Claus Fröhlich reject the statement that the warming observed in the global mean surface temperature record since about 1850 is the result of solar variations.[121] Lockwood and Fröhlich conclude, "the observed rapid rise in global mean temperatures seen after 1985 cannot be ascribed to solar variability, whichever of the mechanisms is invoked and no matter how much the solar variation is amplified."[121]

Aerosols forcing

The hiatus in warming from the 1940s to 1960s is generally attributed to cooling effect of sulphate aerosols.[122][123] More recently, this forcing has (relatively) declined, which may have enhanced warming, though the effect is regionally varying. See global dimming. Another example of this is in Ruckstuhl's paper who found a 60% reduction in aerosol concentrations over Europe causing solar brightening:[124]

... the direct aerosol effect had an approximately five times larger impact on climate forcing than the indirect aerosol and other cloud effects. The overall aerosol and cloud induced surface climate forcing is ~ 1 W m−2 decade−1 and has most probably strongly contributed to the recent rapid warming in Europe.

Analysis of temperature records

Instrumental record of surface temperature

There have been attempts to raise public controversy over the accuracy of the instrumental temperature record on the basis of the urban heat island effect, the quality of the surface station network, and assertions that there have been unwarranted adjustments to the temperature record.[126][127]

Weather stations that are used to compute global temperature records are not evenly distributed over the planet, and their distribution has changed over time. There were a small number of weather stations in the 1850s, and the number did not reach the current 3000+ until the 1951 to 1990 period[128]

The 2001 IPCC Third Assessment Report (TAR) acknowledged that the urban heat island is an important local effect, but cited analyses of historical data indicating that the effect of the urban heat island on the global temperature trend is no more than 0.05 °C (0.09 °F) degrees through 1990.[129] Peterson (2003) found no difference between the warming observed in urban and rural areas.[130]

Parker (2006) found that there was no difference in warming between calm and windy nights. Since the urban heat island effect is strongest for calm nights and is weak or absent on windy nights, this was taken as evidence that global temperature trends are not significantly contaminated by urban effects.[131] Pielke and Matsui published a paper disagreeing with Parker's conclusions.[132]

In 2005, Roger A. Pielke and Stephen McIntyre criticized the US instrumental temperature record and adjustments to it, and Pielke and others criticized the poor quality siting of a number of weather stations in the United States.[133][134] In 2007, Anthony Watts began a volunteer effort to photographically document the siting quality of these stations.[135] The Journal of Geophysical Research – Atmospheres subsequently published a study by Menne et al. which examined the record of stations picked out by Watts' Surfacestations.org and found that, if anything, the poorly sited stations showed a slight cool bias rather than the warm bias which Watts had anticipated.[136][137]

The Berkeley Earth Surface Temperature group carried out an independent assessment of land temperature records, which examined issues raised by deniers, such as the urban heat island effect, poor station quality, and the risk of data selection bias. The preliminary results, made public in October 2011, found that these factors had not biased the results obtained by NOAA, the Hadley Centre together with the Climatic Research Unit (HadCRUT) and NASA's GISS in earlier studies. The group also confirmed that over the past 50 years the land surface warmed by 0.911 °C, and their results closely matched those obtained from these earlier studies. The four papers they had produced had been submitted for peer review.[138][139][140][141]

Tropospheric temperature

General circulation models and basic physical considerations predict that in the tropics the temperature of the troposphere should increase more rapidly than the temperature of the surface. A 2006 report to the U.S. Climate Change Science Program noted that models and observations agreed on this amplification for monthly and interannual time scales but not for decadal time scales in most observed data sets. Improved measurement and analysis techniques have reconciled this discrepancy: corrected buoy and satellite surface temperatures are slightly cooler and corrected satellite and radiosonde measurements of the tropical troposphere are slightly warmer.[142] Satellite temperature measurements show that tropospheric temperatures are increasing with "rates similar to those of the surface temperature", leading the IPCC to conclude that this discrepancy is reconciled.[143]

Antarctica cooling

There has been a public dispute regarding the apparent contradiction in the observed behavior of Antarctica, as opposed to the global rise in temperatures measured elsewhere in the world. This became part of the public debate in the global warming controversy, particularly between advocacy groups of both sides in the public arena, as well as the popular media.[144][145][146]

In contrast to the popular press, there is no evidence of a corresponding controversy in the scientific community. Observations unambiguously show the Antarctic Peninsula to be warming. The trends elsewhere show both warming and cooling but are smaller and dependent on season and the timespan over which the trend is computed.[147] A study released in 2009, combined historical weather station data with satellite measurements to deduce past temperatures over large regions of the continent, and these temperatures indicate an overall warming trend. One of the paper's authors stated, "We now see warming is taking place on all seven of the earth's continents in accord with what models predict as a response to greenhouse gases."[148] According to 2011 paper by Ding, et al., "The Pacific sector of Antarctica, including both the Antarctic Peninsula and continental West Antarctica, has experienced substantial warming in the past 30 years."[149][150]

This controversy began with the misinterpretation of the results of a 2002 paper by Doran et al.,[151][152] which found "Although previous reports suggest slight recent continental warming, our spatial analysis of Antarctic meteorological data demonstrates a net cooling on the Antarctic continent between 1966 and 2000, particularly during summer and autumn."[151] Later the controversy was popularized by Michael Crichton's 2004 fiction novel State of Fear,[153] who advocated "skepticism" of global warming.[154][155] This novel has a docudrama plot based upon the idea that there is a deliberately alarmist conspiracy behind global warming activism. One of the characters argues "data show that one relatively small area called the Antarctic Peninsula is melting and calving huge icebergs... but the continent as a whole is getting colder, and the ice is getting thicker." As a basis for this plot twist, Crichton cited the peer reviewed scientific article by Doran, et al.[151] Peter Doran, the lead author of the paper cited by Crichton, stated "... our results have been misused as 'evidence' against global warming by Crichton in his novel State of Fear ... 'Our study did find that 58 percent of Antarctica cooled from 1966 to 2000. But during that period, the rest of the continent was warming. And climate models created since our paper was published have suggested a link between the lack of significant warming in Antarctica and the ozone hole over that continent."[156]

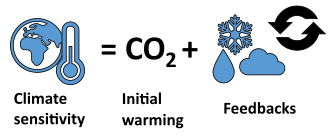

Climate sensitivity

Climate sensitivity is a key measure in climate science and describes how much Earth's surface will warm for a doubling in the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration.[157][158] Its formal definition is: "The change in the surface temperature in response to a change in the atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2) concentration or other radiative forcing."[159]: 2223 This concept helps scientists understand the extent and magnitude of the effects of climate change.

The Earth's surface warms as a direct consequence of increased atmospheric CO2, as well as increased concentrations of other greenhouse gases such as nitrous oxide and methane. The increasing temperatures have secondary effects on the climate system. These secondary effects are called climate feedbacks. Self-reinforcing feedbacks include for example the melting of sunlight-reflecting ice as well as higher evapotranspiration. The latter effect increases average atmospheric water vapour, which is itself a greenhouse gas.

Scientists do not know exactly how strong these climate feedbacks are. Therefore, it is difficult to predict the precise amount of warming that will result from a given increase in greenhouse gas concentrations. If climate sensitivity turns out to be on the high side of scientific estimates, the Paris Agreement goal of limiting global warming to below 2 °C (3.6 °F) will be difficult to achieve.[160]

There are two main kinds of climate sensitivity: the transient climate response is the initial rise in global temperature when CO2 levels double, and the equilibrium climate sensitivity is the larger long-term temperature increase after the planet adjusts to the doubling. Climate sensitivity is estimated by several methods: looking directly at temperature and greenhouse gas concentrations since the Industrial Revolution began around the 1750s, using indirect measurements from the Earth's distant past, and simulating the climate.Infrared iris hypothesis

In 2001, Richard Lindzen proposed a system of compensating meteorological processes involving clouds that tend to stabilize climate change; claiming that increased sea surface temperatures will ultimately lead to more infrared radiation from earth's atmosphere.[161] He tagged this the "Iris hypothesis", or "Infrared Iris".[162] This work has been discussed in a number of papers[163]

Roy Spencer et al. suggested "a net reduction in radiative input into the ocean-atmosphere system" in tropical intraseasonal oscillations "may potentially support" the idea of an "Iris" effect, although they point out that their work is concerned with much shorter time scales.[164]

Other analyses have found that the iris effect is positive feedback rather than the negative feedback proposed by Lindzen.[165]

Temperature projections

James Hansen's 1984 climate model projections versus observed temperatures are updated each year by Dr Mikako Sato of Columbia University.[167] The RealClimate website provides an annual update comparing both Hansen's 1988 model projections and the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report (AR4) climate model projections with observed temperatures recorded by GISS and HadCRUT. The measured temperatures show continuing global warming.[166]

Conventional projections of future temperature increases depend on estimates of future anthropogenic GHG emissions (see SRES), those positive and negative climate change feedbacks that have so far been incorporated into the models, and the climate sensitivity. Models referenced by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) predict that global temperatures are likely to increase by 1.1 to 6.4 °C (2.0 to 11.5 °F) between 1990 and 2100. Others have proposed that temperature increases may be higher than IPCC estimates. One theory is that the climate may reach a "tipping point" where positive feedback effects lead to runaway global warming; such feedbacks include decreased reflection of solar radiation as sea ice melts, exposing darker seawater, and the potential release of large volumes of methane from thawing permafrost.[168] In 1959, Bert Bolin, in a speech to the National Academy of Sciences, predicted that by the year 2000, there would be a 25% increase in carbon dioxide in the atmosphere compared to the levels in 1859. The actual increase by 2000 was about 29%.[169]

In a NASA report published in January 2013, Hansen and Sato noted "the 5-year mean global temperature has been flat for a decade, which we interpret as a combination of natural variability and a slowdown in the growth rate of the net climate forcing."[170][171] Ed Hawkins, of the University of Reading,[172] stated that the "surface temperatures since 2005 are already at the low end of the range of projections derived from 20 climate models. If they remain flat, they will fall outside the models' range within a few years."[170][173] Using the long-term temperature trends for the earth scientists and statisticians conclude that it continues to warm through time.[174]

Forecasts confidence

The IPCC states it has increased confidence in forecasts coming from General Circulation Models or GCMs. Chapter 8 of AR4 reads:

There is considerable confidence that climate models provide credible quantitative estimates of future climate change, particularly at continental scales and above. This confidence comes from the foundation of the models in accepted physical principles and from their ability to reproduce observed features of current climate and past climate changes. Confidence in model estimates is higher for some climate variables (e.g., temperature) than for others (e.g., precipitation). Over several decades of development, models have consistently provided a robust and unambiguous picture of significant climate warming in response to increasing greenhouse gases.[175]

Certain scientists believe this confidence in the models' ability to predict future climate is not earned.[176]

Data archiving and sharing

Scientific journals and funding agencies generally require authors of peer-reviewed research to provide information on archives of data and share sufficient data and methods necessary for a scientific expert on the topic to reproduce the work.[177]

In political controversy over the 1998 and 1999 historic temperature reconstructions widely publicised as the "hockey stick graphs", Mann, Bradley and Hughes as authors of the studies were sent letters on 23 June 2005 from Rep. Joe Barton, chairman of the House Committee on Energy and Commerce and Ed Whitfield, Chairman of the Subcommittee on Oversight and Investigations, demanding full records on the research.[178][179][180] The letters told the scientist to provide not just data and methods, but also personal information about their finances and careers, information about grants provided to the institutions they had worked for, and the exact computer codes used to generate their results.[181]

Sherwood Boehlert, chairman of the House Science Committee, told his fellow Republican Joe Barton it was a "misguided and illegitimate investigation" seemingly intended to "intimidate scientists rather than to learn from them, and to substitute congressional political review for scientific review". The U.S. National Academy of Sciences (NAS) president Ralph Cicerone wrote to Barton proposing that the NAS should appoint an independent panel to investigate. Barton dismissed this offer.[182][183]

On 15 July, Mann wrote giving his detailed response to Barton and Whitfield. He emphasized that the full data and necessary methods information was already publicly available in full accordance with National Science Foundation (NSF) requirements, so that other scientists had been able to reproduce their work. NSF policy was that computer codes are considered the intellectual property of researchers and are not subject to disclosure, but notwithstanding these property rights, the program used to generate the original MBH98 temperature reconstructions had been made available at the Mann et al. public FTP site.[184]

Many scientists protested Barton's demands.[182][185] Alan I. Leshner wrote to him on behalf of the American Association for the Advancement of Science stating that the letters gave "the impression of a search for some basis on which to discredit these particular scientists and findings, rather than a search for understanding", He stated that Mann, Bradley and Hughes had given out their full data and descriptions of methods.[186][187] A Washington Post editorial on 23 July which described the investigation as harassment quoted Bradley as saying it was "intrusive, far-reaching and intimidating", and Alan I. Leshner of the AAAS describing it as unprecedented in the 22 years he had been a government scientist; he thought it could "have a chilling effect on the willingness of people to work in areas that are politically relevant".[181] Congressman Boehlert said the investigation was as "at best foolhardy" with the tone of the letters showing the committee's inexperience in relation to science.[186]

Barton was given support by global warming sceptic Myron Ebell of the Competitive Enterprise Institute, who said "We've always wanted to get the science on trial ... we would like to figure out a way to get this into a court of law," and "this could work".[186] In his Junk Science column on Fox News, Steven Milloy said Barton's inquiry was reasonable.[188] In September 2005 David Legates alleged in a newspaper op-ed that the issue showed climate scientists not abiding by data access requirements and suggested that legislators might ultimately take action to enforce them.[189]

Boehlert commissioned the U.S. National Academy of Sciences to appoint an independent panel which investigated the issues and produced the North Report which confirmed the validity of the science. At the same time, Barton arranged with statistician Edward Wegman to back up the attacks on the "hockey stick" reconstructions. The Wegman Report repeated allegations about disclosure of data and methods, but Wegman failed to provide the code and data used by his team, despite repeated requests, and his report was subsequently found to contain plagiarized content. The "hockey stick" reconstructions and issues of data archiving and sharing subsequently became central features of the Climatic Research Unit email controversy.

Funding for scientists who are skeptics or deniers

The Global Climate Coalition was an industry coalition that funded several scientists who expressed skepticism about global warming. In the year 2000, several members left the coalition when they became the target of a national divestiture campaign run by John Passacantando and Phil Radford at Ozone Action. According to The New York Times, when Ford Motor Company was the first company to leave the coalition, it was "the latest sign of divisions within heavy industry over how to respond to global warming".[190][191] After that, between December 1999 and early March 2000, the GCC was deserted by Daimler-Chrysler, Texaco, energy firm the Southern Company and General Motors.[192] The Global Climate Coalition closed in 2002, or in their own words, 'deactivated'.[193]

Documents obtained by Greenpeace under the US Freedom of Information Act show that the Charles G. Koch Foundation gave climate change denier Willie Soon two grants totaling $175,000 in 2005/6 and again in 2010. Multiple grants to Soon from the American Petroleum Institute between 2001 and 2007, totaled $274,000, and from ExxonMobil totaled $335,000 between 2005 and 2010. Other coal and oil industry sources which funded him include the Mobil Foundation, the Texaco Foundation and the Electric Power Research Institute. Soon, acknowledging that he received this money, stated unequivocally that he has "never been motivated by financial reward in any of my scientific research".[18] In February 2015, Greenpeace disclosed papers documenting that Soon failed to disclose to academic journals funding including more than $1.2 million from fossil fuel industry related interests including ExxonMobil, the American Petroleum Institute, the Charles G. Koch Charitable Foundation and the Southern Company.[194][195][196] In 2003, The Independent Institute release a study that reported the evidence for imminent global warming found during the Clinton administration was based on now-dated satellite findings and wrote off the evidence and findings as a product of "bad science". It was noted that ExxonMobil's contributions to The Independent Institute totaled $20,000 since 2002.[197] The George C. Marshall Institute received $630,000 in funding for climate change research from ExxonMobil between 1998 and 2005. Exxon Mobil also gave $472,000 in funding to The Board of Academic and Scientific Advisors for the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow from 1998 to 2005. Frederick Seitz, well known as "the godfather of global warming skepticism", served as both Chairman Emeritus of The George C. Marshall Institute and a board member of the Committee for a Constructive Tomorrow from 1998 to 2005.[198]

To investigate how widespread such hidden funding was, senators Barbara Boxer, Edward Markey and Sheldon Whitehouse wrote to a number of companies. Koch general counsel refused the request and said it would infringe the company's first amendment rights.[199]

The Greenpeace research project ExxonSecrets, and George Monbiot writing in The Guardian, as well as various academics,[200][201] have linked several scientists who are climate deniers—Fred Singer, Fred Seitz and Patrick Michaels—to organizations funded by ExxonMobil and Philip Morris for the purpose of promoting global warming denial. These organizations include the Cato Institute and the Heritage Foundation.[202] Similarly, groups employing global warming deniers, such as the George C. Marshall Institute, have been criticized for their ties to fossil fuel companies.[203]

On 2 February 2007, The Guardian stated[204][205] that Kenneth Green, a visiting scholar with AEI, had sent letters[206] to scientists in the UK and the U.S., offering US$10,000 plus travel expenses and other incidental payments in return for essays with the purpose of "highlight[ing] the strengths and weaknesses of the IPCC process", specifically regarding the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report.[207]

A furor was raised when it was revealed that the Intermountain Rural Electric Association (an energy cooperative that draws a significant portion of its electricity from coal-burning power plants) donated $100,000 to Patrick Michaels and his group, New Hope Environmental Services, and solicited additional private donations from its members.[208][209][unreliable source?][210]

The Union of Concerned Scientists produced a report titled 'Smoke, Mirrors & Hot Air',[211] that criticizes ExxonMobil for "underwriting the most sophisticated and most successful disinformation campaign since the tobacco industry" and for "funnelling about $16 million between 1998 and 2005 to a network of ideological and advocacy organizations that manufacture uncertainty on the issue". In 2006, Exxon said that it was no longer going to fund these groups[212] though that statement has been challenged by Greenpeace.[213]

The Center for the Study of Carbon Dioxide and Global Change, a denialist group, when confronted about the funding of a video they put together ($250,000 for "The Greening of Planet Earth" from an oil company) stated, "We applaud Western Fuels for their willingness to publicize a side of the story that we believe to be far more correct than what at one time was 'generally accepted'. But does this mean that they fund The Center? Maybe it means that we fund them!"[214]

Donald Kennedy, editor-in-chief of Science, has said that deniers such as Michaels are lobbyists more than researchers, and "I don't think it's unethical any more than most lobbying is unethical," he said. He said donations to deniers amounts to "trying to get a political message across".[215]

Global warming denier Reid Bryson said in June 2007, "There is a lot of money to be made in this ... If you want to be an eminent scientist you have to have a lot of grad students and a lot of grants. You can't get grants unless you say, 'Oh global warming, yes, yes, carbon dioxide'."[216] Similar positions have been advanced by University of Alabama, Huntsville climate scientist Roy Spencer, Spencer's University of Alabama, Huntsville colleague and IPCC contributor John Christy, University of London biogeographer Philip Stott,[217] Accuracy in Media,[218] and Ian Plimer.[219]

Richard Lindzen, the Alfred P. Sloan Professor of Meteorology at MIT, said, "[in] the winter of 1989 Reginald Newell, a professor of meteorology [at MIT], lost National Science Foundation funding for data analyses that were failing to show net warming over the past century." Lindzen also suggested that four other scientists "apparently" lost their funding or positions after questioning the scientific underpinnings of global warming.[220] Lindzen himself has been the recipient of money from energy interests such as OPEC and the Western Fuels Association, including "$2,500 a day for his consulting services",[221] as well as funding from US federal sources including the National Science Foundation, the Department of Energy, and NASA.[222]

Political questions

In the U.S. global warming is often a partisan political issue.[226] Republicans tend to oppose action against a threat that they regard as unproven, while Democrats tend to support actions that they believe will reduce global warming and its effects through the control of greenhouse gas emissions.[227]

Climate change is also a highly politicised issue in Australia, to the point that it is sometimes referred to as a "culture war".[228][229][230] Australian conservatives, with the support of strongly climate-skeptical media, have long opposed climate change mitigation and changes to energy policy. This is partly a strategy to foster the support of the country's coal and the fossil fuel industry, which are highly influential and a large employer in the country.[228][229]

When discussing the politicisation of IPCC assessment reports climatologist Kevin E. Trenberth stated:

The SPM [Summary for policymakers] was approved line by line by governments ... The argument here is that the scientists determine what can be said, but the governments determine how it can best be said. Negotiations occur over wording to ensure accuracy, balance, clarity of message, and relevance to understanding and policy. The IPCC process is dependent on the good will of the participants in producing a balanced assessment. However, in Shanghai, it appeared that there were attempts to blunt, and perhaps obfuscate, the messages in the report, most notably by Saudi Arabia. This led to very protracted debates over wording on even bland and what should be uncontroversial text ... The most contentious paragraph in the IPCC (2001) SPM was the concluding one on attribution. After much debate, the following was carefully crafted: "In the light of new evidence, and taking into account the remaining uncertainties, most of the observed warming over the last 50 years is likely to have been due to the increase in greenhouse-gas concentrations."[231]

As more evidence has become available over the existence of global warming, debate has moved to further controversial issues,[232] including:

- The social and environmental impacts

- The appropriate response to climate change

- Whether decisions require less uncertainty

The single largest issue is the importance of a few degrees rise in temperature:

Most people say, "A few degrees? So what? If I change my thermostat a few degrees, I'll live fine." ... [The] point is that one or two degrees is about the experience that we have had in the last 10,000 years, the era of human civilization. There haven't been—globally averaged, we're talking—fluctuations of more than a degree or so. So we're actually getting into uncharted territory from the point of view of the relatively benign climate of the last 10,000 years, if we warm up more than a degree or two. (Stephen H. Schneider[233])

There is debate[until when?] on whether action (such as the restrictions on the use of fossil fuels to reduce carbon-dioxide emissions) should be taken now or in the near future. Because of the economic ramifications of such restrictions, there are those, including the Cato Institute, a libertarian think tank, who argue that the negative economic effects of emission controls outweigh the environmental benefits.[234] They state that even if global warming is caused solely by the burning of fossil fuels, restricting their use would have more damaging effects on the world economy than the increases in global temperature:[235]

The linkage between coal, electricity, and economic growth in the United States is as clear as it can be. And it is required for the way we live, the way we work, for our economic success, and for our future. Coal-fired electricity generation. It is necessary. (Fred Palmer, President of Western Fuels Association[235])

Conversely, others argue that early action to reduce emissions would help avoid much greater economic costs later, and would reduce the risk of catastrophic, irreversible change.[236] In his December 2006 book, Hell and High Water, Joseph J. Romm:

discusses the urgency to act and the sad fact that America is refusing to do so...

On a local or regional level, some specific effects of global warming might be considered beneficial.[237]

Council on Foreign Relations senior fellow Walter Russell Mead argues that the 2009 Copenhagen Summit failed because environmentalists have changed from "Bambi to Godzilla". According to Mead, environmentalists used to represent the skeptical few who made valid arguments against big government programs which tried to impose simple but massive solutions on complex situations. Environmentalists' more recent advocacy for big economic and social intervention against global warming, according to Mead, has made them, "the voice of the establishment, of the tenured, of the technocrats" and thus has lost them the support of a public which is increasingly skeptical of global warming.[238]

Debate over most effective response to warming

In recent years some climate change skeptics have changed their positions regarding global warming. Ronald Bailey, author of Global Warming and Other Eco-Myths (published by the Competitive Enterprise Institute in 2002), stated in 2005, "Anyone still holding onto the idea that there is no global warming ought to hang it up."[239] By 2007, he wrote "Details like sea level rise will continue to be debated by researchers, but if the debate over whether or not humanity is contributing to global warming wasn't over before, it is now.... as the new IPCC Summary makes clear, climate change Pollyannaism is no longer looking very tenable."[240]

"There are alternatives to its [the climate-change crusade's] insistence that the only appropriate policy response is steep and immediate emissions reductions.... a greenhouse-gas-emissions cap ultimately would constrain energy production. A sensible climate policy would emphasize building resilience into our capacity to adapt to climate changes.... we should consider strategies of adaptation to a changing climate. A rise in the sea level need not be the end of the world, as the Dutch have taught us." says Steven F. Hayward of American Enterprise Institute, a conservative think-tank.[241] Hayward also advocates the use of "orbiting mirrors to rebalance the amounts of solar radiation different parts of the earth receive"—the space sunshade example of so-called geoengineering for solar radiation management.[citation needed]

In 2001, Richard Lindzen, asked whether it was necessary to try to reduce CO2 emissions, said that responses needed to be prioritized. "You can't just say, 'No matter what the cost, and no matter how little the benefit, we'll do this'. If we truly believe in warming, then we've already decided we're going to adjust...The reason we adjust to things far better than Bangladesh is that we're richer. Wouldn't you think it makes sense to make sure we're as robust and wealthy as possible? And that the poor of the world are also as robust and wealthy as possible?"[242]

Others argue that if developing nations reach the wealth level of the United States this could greatly increase CO2 emissions and consumption of fossil fuels. Large developing nations such as India and China are predicted to be major emitters of greenhouse gases in the next few decades as their economies grow.[243][244]

The conservative National Center for Policy Analysis whose "Environmental Task Force" contains a number of climate change deniers including Sherwood Idso and S. Fred Singer[245] says, "The growing consensus on climate change policies is that adaptation will protect present and future generations from climate-sensitive risks far more than efforts to restrict CO2 emissions."[246]

The adaptation-only plan is also endorsed by oil companies like ExxonMobil, "ExxonMobil's plan appears to be to stay the course and try to adjust when changes occur. The company's plan is one that involves adaptation, as opposed to leadership,"[247] says this Ceres report.[248]

Gregg Easterbrook characterized himself as having "a long record of opposing alarmism". In 2006, he stated, "based on the data I'm now switching sides regarding global warming, from skeptic to convert."[249]

The George W. Bush administration also voiced support for an adaptation-only policy in the US in 2002. "In a stark shift for the Bush administration, the United States has sent a climate report [U.S. Climate Action Report 2002] to the United Nations detailing specific and far-reaching effects it says global warming will inflict on the American environment. In the report, the administration also for the first time places most of the blame for recent global warming on human actions—mainly the burning of fossil fuels that send heat-trapping greenhouse gases into the atmosphere." The report however "does not propose any major shift in the administration's policy on greenhouse gases. Instead it recommends adapting to inevitable changes instead of making rapid and drastic reductions in greenhouse gases to limit warming."[250] This position apparently precipitated a similar shift in emphasis at the COP 8 climate talks in New Delhi several months later,[251] "The shift satisfies the Bush administration, which has fought to avoid mandatory cuts in emissions for fear it would harm the economy. 'We're welcoming a focus on more of a balance on adaptation versus mitigation', said a senior American negotiator in New Delhi. 'You don't have enough money to do everything.'"[252][253] The White House emphasis on adaptation was not well received however:

Despite conceding that our consumption of fossil fuels is causing serious damage and despite implying that current policy is inadequate, the Report fails to take the next step and recommend serious alternatives. Rather, it suggests that we simply need to accommodate to the coming changes. For example, reminiscent of former Interior Secretary Hodel's proposal that the government address the hole in the ozone layer by encouraging Americans to make better use of sunglasses, suntan lotion and broad-brimmed hats, the Report suggests that we can deal with heat-related health impacts by increased use of air-conditioning ... Far from proposing solutions to the climate change problem, the Administration has been adopting energy policies that would actually increase greenhouse gas emissions. Notably, even as the Report identifies increased air conditioner use as one of the 'solutions' to climate change impacts, the Department of Energy has decided to roll back energy efficiency standards for air conditioners.

— Letter from 11 State Attorneys General to George W. Bush., [254]

Some find this shift and attitude disingenuous and indicative of an inherent bias against prevention (i.e. reducing emissions/consumption) and for the prolonging of profits to the oil industry at the expense of the environment. "Now that the dismissal of climate change is no longer fashionable, the professional deniers are trying another means of stopping us from taking action. It would be cheaper, they say, to wait for the impacts of climate change and then adapt to them" says writer and environmental activist George Monbiot[255] in an article addressing the supposed economic hazards of addressing climate change. Others argue that adaptation alone will not be sufficient.[256] See also Copenhagen Consensus.

Though not emphasized to the same degree as mitigation, adaptation to a climate certain to change has been included as a necessary component in the discussion as early as 1992,[257] and has been all along.[citation needed] However it was not to the exclusion, advocated by the deniers, of preventive mitigation efforts, and therein, say carbon cutting proponents, lies the difference.[258]

Another highly debated potential climate change mitigation strategy is carbon emission trading (Cap and Trade) due to its direct relationship with the economy.[259]

In November 2016, the Paris Agreement went into effect.[260]

Political pressure on scientists

Actions under the Bush Administration

A survey of climate scientists which was reported to the US House Oversight and Government Reform Committee in 2007, noted "Nearly half of all respondents perceived or personally experienced pressure to eliminate the words 'climate change', 'global warming' or other similar terms from a variety of communications." These scientists were pressured to tailor their reports on global warming to fit the Bush administration's climate change denial. In some cases, this occurred at the request of former oil-industry lobbyist Phil Cooney, who worked for the American Petroleum Institute before becoming chief of staff at the White House Council on Environmental Quality (he resigned in 2005, before being hired by ExxonMobil).[261] In June 2008, a report by NASA's Office of the Inspector General concluded that NASA staff appointed by the White House had censored and suppressed scientific data on global warming in order to protect the Bush administration from controversy close to the 2004 presidential election.[262]

Officials, such as Philip Cooney repeatedly edited scientific reports from US government scientists,[263] many of whom, such as Thomas Knutson, were ordered to refrain from discussing climate change and related topics.[264][265][266]

Climate scientist James E. Hansen, director of NASA's Goddard Institute for Space Studies, wrote in a widely cited New York Times article[267] in 2006, that his superiors at the agency were trying to "censor" information "going out to the public". NASA denied this, saying that it was merely requiring that scientists make a distinction between personal, and official government views, in interviews conducted as part of work done at the agency. When multiple scientists working at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration made similar complaints;[268] government officials again said they were enforcing long-standing policies requiring government scientists to clearly identify personal opinions as such when participating in public interviews and forums.[citation needed]

In 2006, the BBC current affairs program Panorama investigated the issue, and was told, "scientific reports about global warming have been systematically changed and suppressed."[269]

According to an Associated Press release on 30 January 2007:

Climate scientists at seven government agencies say they have been subjected to political pressure aimed at downplaying the threat of global warming.

The groups presented a survey that shows two in five of the 279 climate scientists who responded to a questionnaire complained that some of their scientific papers had been edited in a way that changed their meaning. Nearly half of the 279 said in response to another question that at some point they had been told to delete reference to "global warming" or "climate change" from a report.[270]

The survey was published as a joint report the Union of Concerned Scientists and the Government Accountability Project.[271]

Pressure from the general public and private organizations

Scientists who agree with the consensus view have sometimes expressed concerns over what they view as sensationalism of global warming by interest groups and the press. For example, Mike Hulme, director of the Tyndall Centre for Climate Research, wrote how increasing use of pejorative terms like "catastrophic", "chaotic" and "irreversible", had altered the public discourse around climate change: "This discourse is now characterised by phrases such as 'climate change is worse than we thought', that we are approaching 'irreversible tipping in the Earth's climate', and that we are 'at the point of no return'. I have found myself increasingly chastised by climate change campaigners when my public statements and lectures on climate change have not satisfied their thirst for environmental drama and exaggerated rhetoric."[272]

In addition, many prominent climate scientists have reported increasingly severe hostility from members of the public. The FBI told ABC News that it was looking into a spike in threatening emails sent to climate scientists, while a white supremacist website posted pictures of several climate scientists with the word "Jew" next to each image. One climate scientist interviewed by ABC had a dead animal dumped on his doorstep and now frequently has to travel with bodyguards.[273]

2010 Virginia Attorney General investigation

In April 2010, then Virginia Attorney General and Republican Ken Cuccinelli claimed that leading climate scientist Michael E. Mann had possibly violated state fraud laws, and without providing any evidence of wrongdoing, filed the Attorney General of Virginia's climate science investigation. As part a civil investigation, Cuccinelli's office served the University of Virginia with subpoenas demanding they provide a wide range of records broadly related to five research grants Mann had obtained as an assistant professor at the university from 1999 to 2005. This litigation was widely criticized in the academic community as politically motivated and likely to have a chilling effect on future research.[274][275] UVA filed a court petition and the judge dismissed Cuccinelli's demand on the grounds that no justification had been shown for the investigation.[276] Cuccinelli then issued a revised subpoena, and appealed the case to the Virginia Supreme Court which ruled in March 2012 that Cuccinelli did not have the authority to make these demands. The outcome was hailed as a victory for academic freedom.[277][278]

See also

- Global warming hiatus

- Attitude polarization

- Climatic Research Unit documents

- Climatic Research Unit email controversy

- Criticism of the IPCC Fourth Assessment Report

- Global warming conspiracy theory

- Manufactured controversy

- Science wars

- Global cooling

- Skeptical Science

- Environmental skepticism

- Right-wing antiscience

- Politicization of science

Notes

- ^

Oreskes, Naomi (December 2004). "Beyond the Ivory Tower: The Scientific Consensus on Climate Change". Science. 306 (5702): 1686. doi:10.1126/science.1103618. PMID 15576594.

Such statements suggest that there might be substantive disagreement in the scientific community about the reality of anthropogenic climate change. This is not the case. [...] Politicians, economists, journalists, and others may have the impression of confusion, disagreement, or discord among climate scientists, but that impression is incorrect.

- ^

America's Climate Choices: Panel on Advancing the Science of Climate Change; National Research Council (2010). Advancing the Science of Climate Change. Washington, D.C.: The National Academies Press. ISBN 978-0-309-14588-6. Archived from the original on 29 May 2014. Retrieved 19 February 2014.