Climate change and civilizational collapse

Climate change and civilizational collapse refers to a hypothetical risk of the impacts of climate change reducing global socioeconomic complexity to the point complex human civilization effectively ends around the world, with humanity reduced to a less developed state. This hypothetical risk is typically associated with the idea of a massive reduction of human population caused by the direct and indirect impacts of climate change, and often, it is also associated with a permanent reduction of the Earth's carrying capacity. Finally, it is sometimes suggested that a civilizational collapse caused by climate change would soon be followed by human extinction.

Some researchers connect historical examples of societal collapse with adverse changes in local and/or global weather patterns. In particular, the 4.2-kiloyear event, a millennial-scale megadrought which took place in Africa and Asia between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago, has been linked with the collapse of the Old Kingdom in Egypt, the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia, the Liangzhu culture in the lower Yangtze River area and the Indus Valley Civilization.[2][3] In Europe, the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century, which was defined by events such as crop failure and the Thirty Years' War, took place during the Little Ice Age. In 2011, a general connection was proposed between adverse climate variations and long-term societal crises during the preindustrial times.[4] However, all of these events were limited to individual human societies: a collapse of the entire human civilization would be historically unprecedented.

Some of the more extreme warnings of civilizational collapse caused by climate change, such as a claim that civilization is highly likely to end by 2050, have attracted strong rebutals from scientists. [5][6] The 2022 IPCC Sixth Assessment Report projects that human population would be in a range between 8.5 billion and 11 billion people by 2050. By the year 2100, the median population projection is at 11 billion people, while the maximum population projection is close to 16 billion people. The lowest projection for 2100 is around 7 billion, and this decline from present levels is primarily attributed to "rapid development and investment in education", with those projections associated with some of the highest levels of economic growth.[7] However, a minority of climate scientists have argued that higher levels of warming—between about 3 °C (5.4 °F) to 5 °C (9.0 °F) over preindustrial temperatures—may be incompatible with civilization, or that the lives of several billion people could no longer be sustained in such a world.[8][9][10][11] In 2022, they have called for a so-called "climate endgame" research agenda into the probability of these risks, which had attracted significant media attention and some scientific controversy.[12][13][14]

Some of the most high-profile writing on climate change and civilizational collapse has been written by non-scientists. Notable examples include "The Uninhabitable Earth"[15] by David Wallace-Wells and "What if we stopped pretending?" by Jonathan Franzen,[16] which were both criticized for scientific inaccuracy.[17][18] Climate change in popular culture is commonly represented in a highly exaggerated manner as well. Opinion polling has provided evidence that people across the world believe that the outcomes of civilizational collapse or human extinction are much more likely than the scientists believe them to be.[19][20]

Suggested historical examples[edit]

Archeologists identified signs of a megadrought for a millennium between 5,000 and 4,000 years ago in Africa and Asia. The drying of the Green Sahara not only turned it into a desert but also disrupted the monsoon seasons in South and Southeast Asia and caused flooding in East Asia, which prevented successful harvest and the development of complex culture. It coincided with and may have caused the decline and the fall of the Akkadian Empire in Mesopotamia and the Indus Valley Civilization.[21] The dramatic shift in climate is known as the 4.2-kiloyear event.[22]

The highly advanced Indus Valley Civilization took roots around 3000 BC in what is now northwestern India and Pakistan and collapsed around 1700 BC. Since the Indus script has yet to be deciphered, the causes of its de-urbanization[23] remain a mystery, but there is some evidence pointing to natural disasters.[24] Signs of a gradual decline began to emerge in 1900 BC, and two centuries later, most of the cities had been abandoned. Archeological evidence suggests an increase in interpersonal violence and in infectious diseases like leprosy and tuberculosis.[25][26] Historians and archeologists believe that severe and long-lasting drought and a decline in trade with Egypt and Mesopotamia caused the collapse.[27] Evidence for earthquakes has also been discovered. Sea level changes are also found at two possible seaport sites along the Makran coast which are now inland. Earthquakes may have contributed to decline of several sites by direct shaking damage or by changes in sea level or in water supply.[28][29][30]

More generally, recent research pointed to climate change as a key player in the decline and fall of historical societies in China, the Middle East, Europe, and the Americas. In fact, paleoclimatogical temperature reconstruction suggests that historical periods of social unrest, societal collapse, and population crash and significant climate change often occurred simultaneously. A team of researchers from Mainland China and Hong Kong were able to establish a causal connection between climate change and large-scale human crises in pre-industrial times. Short-term crises may be caused by social problems, but climate change was the ultimate cause of major crises, starting with economic depressions.[31] Moreover, since agriculture is highly dependent on climate, any changes to the regional climate from the optimum can induce crop failures.[32]

A more recent example is the General Crisis of the Seventeenth Century in Europe, which was a period of inclement weather, crop failure, economic hardship, extreme intergroup violence, and high mortality because of the Little Ice Age. The Maunder Minimum involved sunspots being exceedingly rare. Episodes of social instability track the cooling with a time lap of up to 15 years, and many developed into armed conflicts, such as the Thirty Years' War (1618–1648),[31] which started as a war of succession to the Bohemian throne. Animosity between Protestants and Catholics in the Holy Roman Empire (in modern-day Germany) added fuel to the fire. Soon, it escalated to a huge conflict that involved all major European powers and devastated much of Germany. When the war had ended, some regions of the empire had seen their populations drop by as much as 70%.[33][34] However, not all societies faced crises during this period. Tropical countries with high carrying capacities and trading economies did not suffer much because the changing climate did not induce an economic depression in those places.[31]Modern discussion[edit]

2000s[edit]

As early as in 2004, a book titled Ecocriticism explored the connection between apocalypticism as expressed in religious contexts, and the secular apocalyptic interpretations of climate and environmental issues.[35] It argued that the tragic (preordained, with clearly delineated morality) or comic (focused on human flaws as opposed to inherent inevitability) apocalyptic framing was seen in the past works on environment, such as Rachel Carson's Silent Spring (1962), Paul and Anne Ehrlich's The Population Bomb (1972), and Al Gore's Earth in the Balance (1992).[36][37]

In the mid-2000s, James Lovelock gave predictions to the British newspapers The Independent and The Guardian, where he suggested that much of Europe will have turned to desert and "billions of us will die and the few breeding pairs of people that survive will be in the Arctic where the climate remains tolerable" by the end of the 21st century.[38][39] In 2008, he was quoted in The Guardian as saying that 80% of humans will perish by 2100, and that the climate change responsible for that will last 100,000 years.[40] By 2012, he admitted that climate change had proceeded slower than he expected.[41]

2010s-present[edit]

In late 2010s, several articles have attracted attention for their predictions of apocalyptic impacts caused by climate change. Firstly, there was "The Uninhabitable Earth",[15] a July 2017 New York magazine article by David Wallace-Wells, which had become the most-read story in the history of the magazine,[42] and was later adapted into a book. Another was "What if we stopped pretending?", an article written for The New Yorker by Jonathan Franzen in September 2019.[16] Both articles were heavily criticized by the fact-checking organization Climate Feedback for the numerous inaccuracies about tipping points in the climate system and other aspects of climate change research.[17][18]

Other examples of this genre include "What Comes After the Coming Climate Anarchy?", a year 2022 article for TIME magazine by Parag Khanna, which had asserted that hundreds of millions of people dying in the upcoming years and the global population standing at 6 billion by the year 2050 was a plausible worst-case scenario.[43] Further, some reports, such as "the 2050 scenario" from the Australian Breakthrough – National Centre for Climate Restoration[44] and the self-published Deep Adaptation paper by Jem Bendell[45] had attracted substantial media coverage by making allegations that the outcomes of climate change are underestimated by the conventional scientific process.[46][47][48][49][50][51] Those reports did not go through the peer review process, and the scientific assessment of these works finds them of very low credibility.[5][52]

Notably, subsequent writing by David Wallace-Wells had stepped back from the claims he made in either version of The Uninhabitable Earth. In 2022, he authored a feature article for The New York Times, which was titled "Beyond Catastrophe: A New Climate Reality Is Coming Into View".[53] The following year, Kyle Paoletta argued in Harper's Magazine that the shift in tone made by David Wallace-Wells was indicative of a larger trend in media coverage of climate change taking place.[54]

Scientific consensus and controversy[edit]

The IPCC Sixth Assessment Report projects that human population would be in a range between 8.5 billion and 11 billion people by 2050; the median population projection for the year 2100 is at 11 billion people, while the maximum population projection is close to 16 billion people. The lowest projection for 2100 is around 7 billion, and this decline from present levels is primarily attributed to "rapid development and investment in education", with those projections associated with some of the highest levels of economic growth.[7] In November 2021, Nature surveyed the authors of the first part of the IPCC assessment report: out of 92 respondents, 88% have agreed that the world is experiencing a "climate crisis", yet when asked if they experience "anxiety, grief or other distress because of concerns over climate change?" just 40% answered "Yes, infrequently", with a further 21% responding "Yes, frequently", and the remaining 39% answering "No".[55] Similarly, when a high-profile paper warning of "the challenges of avoiding a ghastly future" was published in Frontiers in Conservation Science, its authors have noted that "even if major catastrophes occur during this interval, they would unlikely affect the population trajectory until well into the 22nd Century", and "there is no way—ethically or otherwise (barring extreme and unprecedented increases in human mortality)—to avoid rising human numbers and the accompanying overconsumption."[56][57]

Only a minority of publishing scientists have been more open to apocalyptic rhetoric. In 2009, Hans Joachim Schellnhuber, the Emeritus Director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, stated that if global warming reached 4 °C (7.2 °F) over the present levels, then the human population would likely be reduced to 1 billion.[8] In 2015, he complained that this remark was frequently misinterpreted as a call for active human population control rather than a prediction.[58] In a January 2019 interview for The Ecologist, he claimed that if we find reasons to give up on action, then there's a very big risk of things turning to an outright catastrophe, with the civilization ending and almost everything which had been built up over the past two thousand years destroyed.[9]

In May 2019, The Guardian interviewed several climate scientists about a world where 4 °C (7.2 °F) of warming over the preindustrial has occurred by 2100: one of them was Johan Rockström, who was reported to state "It’s difficult to see how we could accommodate a billion people or even half of that" in such a scenario.[10] Around the same time, similar claims were made by the Extinction Rebellion activist Roger Hallam, who said in a 2019 interview that climate change may "kill 6 billion people by 2100"—a remark which was soon questioned by the BBC News presenter Andrew Neil[59] and criticized as scientifically unfounded by Climate Feedback.[6] In November 2019, The Guardian article was corrected, acknowledging that Rockström was misquoted and his real remarks were "It’s difficult to see how we could accommodate eight billion people or maybe even half of that".[10]

Climate endgame[edit]

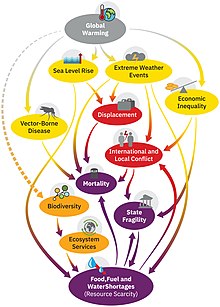

In August 2022, Schellnhuber, Rockström and several other researchers, many of whom were associated with Centre for the Study of Existential Risk at the University of Cambridge, have published a paper in PNAS which argued that a lack of what they called "integrated catastrophe assessment" meant that the risk of societal collapse, or even eventual human extinction caused by climate change and its interrelated impacts such as famine (crop loss, drought), extreme weather (hurricanes, floods), war (caused by the scarce resources), systemic risk (relating to migration, famine, or conflict), and disease was "dangerously underexplored".[13][12] The paper suggested that the following terms should be actively used in the future research.

| Term | Definition |

|---|---|

| Latent risk | Risk that is dormant under one set of conditions but becomes active under another set of conditions. |

| Risk cascade | Chains of risk occurring when an adverse impact triggers a set of linked risks. |

| Systemic risk | The potential for individual disruptions or failures to cascade into a system-wide failure. |

| Extreme climate change | Mean global surface temperature rise of 3 °C (5.4 °F) or more above preindustrial levels by 2100. |

| Extinction risk | The probability of human extinction within a given timeframe. |

| Extinction threat | A plausible and significant contributor to total extinction risk. |

| Societal fragility | The potential for smaller damages to spiral into global catastrophic or extinction risk due to societal vulnerabilities, risk cascades, and maladaptive responses. |

| Societal collapse | Significant sociopolitical fragmentation and/or state failure along with the relatively rapid, enduring, and significant loss capital, and systems identity; this can lead to large-scale increases in mortality and morbidity. |

| Global catastrophic risk | The probability of a loss of 25% of the global population and the severe disruption of global critical systems (such as food) within a given timeframe (years or decades). |

| Global catastrophic threat | A plausible and significant contributor to global catastrophic risk; the potential for climate change to be a global catastrophic threat can be referred to as "catastrophic climate change". |

| Global decimation risk | The probability of a loss of 10% (or more) of global population and the severe disruption of global critical systems (such as food) within a given timeframe (years or decades). |

| Global decimation threat | A plausible and significant contributor to global decimation risk. |

| Endgame territory | Levels of global warming and societal fragility that are judged sufficiently probable to constitute climate change as an extinction threat. |

| Worst-case warming | The highest empirically and theoretically plausible level of global warming. |

The paper was very high-profile, receiving extensive media coverage[13][60] and over 180,000 page views by 2023. It was also the subject of several response papers from other scientists, all of which were also published at PNAS. Most have welcomed its proposals while disagreeing on some of the details of the suggested agenda.[61][62][63][64] However, a response paper authored by Roger Pielke Jr. and fellow University of Colorado Boulder researchers Matthew Burgess and Justin Ritchie was far more critical. They have argued that one of the paper's main arguments—the supposed lack of research into higher levels of global warming—was baseless, as on the contrary, the scenarios of highest global warming called RCP 8.5 and SSP5-8.5 have accounted for around half of all mentions in the "impacts" section of the IPCC Sixth Assessment Report, and SSP3-7, the scenario of slightly lower warming used in some of the paper's graphics, had also assumed greater emissions and more extensive coal use than what had been projected by the International Energy Agency. They have also argued that just as the past projections of overpopulation were used to justify one-child policy in China, a disproportionate focus on apocalyptic scenarios may be used to justify despotism and fascist policies.[14] In response, the authors of the original paper wrote that in their view, catastrophic risks may occur even at lower levels of warming due to risks involving human responses and societal fragility. They also suggested that instead of the one-child policy, a better metaphor for responses to extreme risks research would be the 1980s exploration of the impacts of nuclear winter, which had spurred nuclear disarmament efforts.[65]

Public opinion[edit]

Some public polling shows that beliefs in civilizational collapse or even human extinction have become widespread amongst the general population in many countries. In 2021, a publication in The Lancet surveyed 10,000 people aged 16–25 years in ten countries (Australia, Brazil, Finland, France, India, Nigeria, Philippines, Portugal, the UK, and the US): one of its findings was 55% of respondents agreeing with the statement "humanity is doomed".[19]

In 2020, a survey by a French think tank Jean Jaurès Foundation found that in five developed countries (France, Germany, Italy, the UK and the US), a significant fraction of the population agreed with the statement that "civilization as we know it will collapse in the years to come"; the percentages ranged from 39% in Germany and 52% or 56% in the US and the UK to 65% in France and 71% in Italy.[20]

References[edit]

- ^ "Hint to Coal Consumers". The Selma Morning Times. Selma, Alabama, US. October 15, 1902. p. 4."Carbonic acid" refers to carbon dioxide when dissolved in water.

- ^ Gibbons, Ann (1993). "How the Akkadian Empire Was Hung Out to Dry". Science. 261 (5124): 985. Bibcode:1993Sci...261..985G. doi:10.1126/science.261.5124.985. PMID 17739611.

- ^ Li, Chun-Hai; Li, Yong-Xiang; Zheng, Yun-Fei; Yu, Shi-Yong; Tang, Ling-Yu; Li, Bei-Bei; Cui, Qiao-Yu (August 2018). "A high-resolution pollen record from East China reveals large climate variability near the Northgrippian-Meghalayan boundary (around 4200 years ago) exerted societal influence". Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 512: 156–165. Bibcode:2018PPP...512..156L. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2018.07.031. ISSN 0031-0182. S2CID 133896325.

- ^ Zhang, David D.; Lee, Harry F.; Wang, Cong; Li, Baosheng; Pei, Qing; Zhang, Jane; An, Yulun (18 October 2011). "The causality analysis of climate change and large-scale human crisis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (42): 17296–17301. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104268108. PMC 3198350. PMID 21969578. S2CID 33451915.

- ^ a b "Claim that human civilization could end in 30 years is speculative, not supported with evidence". Climate Feedback. June 4, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "Prediction by Extinction Rebellion's Roger Hallam that climate change will kill 6 billion people by 2100 is unsupported". Climate Feedback. August 22, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Mycoo, M., M. Wairiu, D. Campbell, V. Duvat, Y. Golbuu, S. Maharaj, J. Nalau, P. Nunn, J. Pinnegar, and O. Warrick, 2022: Chapter 3: Mitigation pathways compatible with long-term goals. In Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change [ K. Riahi, R.Schaeffer, J.Arango, K. Calvin, C. Guivarch, T. Hasegawa, K. Jiang, E. Kriegler, R. Matthews, G. P. Peters, A. Rao, S. Robertson, A. M. Sebbit, J. Steinberger, M. Tavoni, D. P. van Vuuren]. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, United Kingdom and New York, NY, USA, pp. 463–464 |doi= 10.1017/9781009157926.005

- ^ a b Kanter, James (13 March 2009). "Scientist: Warming Could Cut Population to 1 Billion". The New York Times. Retrieved 4 May 2010.

- ^ a b "'It's nonlinearity - stupid!'". The Ecologist. 3 January 2019. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ a b c Vince, Gaia (May 18, 2019). "The heat is on over the climate crisis. Only radical measures will work". The Observer. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Carrington, Damian (30 September 2023). "We're not doomed yet': climate scientist Michael Mann on our last chance to save human civilisation". The Guardian. Retrieved 2023-10-19.

- ^ a b c d e f Kemp, Luke; Xu, Chi; Depledge, Joanna; Ebi, Kristie L.; Gibbins, Goodwin; Kohler, Timothy A.; Rockström, Johan; Scheffer, Marten; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim; Steffen, Will; Lenton, Timothy M. (23 August 2022). "Climate Endgame: Exploring catastrophic climate change scenarios". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (34): e2108146119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11908146K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2108146119. PMC 9407216. PMID 35914185.

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

Text was copied from this source, which is available under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

- ^ a b c "Climate endgame: risk of human extinction 'dangerously underexplored'". The Guardian. 1 August 2022. Retrieved 15 September 2022.

- ^ a b c Burgess, Matthew G.; Pielke Jr., Roger; Ritchie, Justin (October 10, 2022). "Catastrophic climate risks should be neither understated nor overstated" (PDF). Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (42): e2214347119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11914347B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2214347119. PMID 36215483.

- ^ a b David Wallace-Wells (July 10, 2017). "The Uninhabitable Earth". New York. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ^ a b Franzen, Jonathan (2019-09-08). "What if We Stopped Pretending the Climate Apocalypse Can Be Stopped?". The New Yorker. Retrieved 2020-01-02.

- ^ a b "Scientists explain what New York Magazine article on "The Uninhabitable Earth" gets wrong". Climate Feedback. July 12, 2017. Retrieved July 13, 2017.

- ^ a b "2°C is not known to be a "point of no return", as Jonathan Franzen claims". Climate Feedback. September 17, 2019. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ a b Hickman, Caroline; Marks, Elizabeth; Pihkala, Panu; Clayton, Susan; Lewandowski, Eric; Mayall, Elouise E; Wray, Britt; Mellor, Catriona; van Susteren, Lise (1 December 2021). "Climate anxiety in children and young people and their beliefs about government responses to climate change: a global survey". The Lancet Planetary Health. 5 (12): e863–e873. doi:10.1016/S2542-5196(21)00278-3. PMID 34895496. S2CID 263447086.

- ^ a b Spinney, Laura (October 11, 2020). "'Humans weren't always here. We could disappear': meet the collapsologists". The Guardian. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Choi, Charles (24 August 2020). "Ancient megadrought may explain civilization's 'missing millennia' in Southeast Asia". Science Magazine. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Collapse of civilizations worldwide defines youngest unit of the Geologic Time Scale". News and Meetings. International Commission on Stratigraphy. Retrieved 15 July 2018.

- ^ Pillalamarri, Akhilesh (2 June 2016). "Revealed: The Truth Behind the Indus Valley Civilization's 'Collapse'". The Diplomat – The Diplomat is a current-affairs magazine for the Asia-Pacific, with news and analysis on politics, security, business, technology and life across the region. Retrieved 10 April 2022.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Robbins-Schug, G.; Gray, K.M.; Mushrif, V.; Sankhyan, A.R. (November 2012). "A Peaceful Realm? Trauma and Social Differentiation at Harappa" (PDF). International Journal of Paleopathology. 2 (2–3): 136–147. doi:10.1016/j.ijpp.2012.09.012. PMID 29539378. S2CID 3933522.

- ^ Robbins-Schug, G.; Blevins, K. Elaine; Cox, Brett; Gray, Kelsey; Mushrif-Tripathy, Veena (December 2013). "Infection, Disease, and Biosocial Process at the End of the Indus Civilization". PLOS ONE. 0084814 (12): e84814. Bibcode:2013PLoSO...884814R. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0084814. PMC 3866234. PMID 24358372.

- ^ Lawler, A. (6 June 2008). "Indus Collapse: The End or the Beginning of an Asian Culture?". Science Magazine. 320 (5881): 1282–1283. doi:10.1126/science.320.5881.1281. PMID 18535222. S2CID 206580637.

- ^ Grijalva, K.A.; Kovach, L.R.; Nur, A.M. (1 December 2006). "Evidence for Tectonic Activity During the Mature Harappan Civilization, 2600-1800 BCE". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2006: T51D–1553. Bibcode:2006AGUFM.T51D1553G.

- ^ Prasad, Manika; Nur, Amos (1 December 2001). "Tectonic Activity during the Harappan Civilization". AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts. 2001: U52B–07. Bibcode:2001AGUFM.U52B..07P.

- ^ Kovach, Robert L.; Grijalva, Kelly; Nur, Amos (1 October 2010). Earthquakes and civilizations of the Indus Valley: A challenge for archaeoseismology. Geological Society of America Special Papers. Vol. 471. pp. 119–127. doi:10.1130/2010.2471(11). ISBN 978-0-8137-2471-3.

- ^ a b c Zhang, David D.; Lee, Harry F.; Wang, Cong; Li, Baosheng; Pei, Qing; Zhang, Jane; An, Yulun (18 October 2011). "The causality analysis of climate change and large-scale human crisis". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 108 (42): 17296–17301. doi:10.1073/pnas.1104268108. PMC 3198350. PMID 21969578. S2CID 33451915.

- ^ Zhang, David D.; Brecke, Peter; Lee, Harry F.; He, Yuan-Qing; Zhang, Jane (4 December 2007). Ehrlich, Paul R. (ed.). "Global climate change, war, and population decline in recent human history". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 104 (49): 19214–19219. Bibcode:2007PNAS..10419214Z. doi:10.1073/pnas.0703073104. PMC 2148270. PMID 18048343.

- ^ National Geographic 2007, pp. 190–191.

- ^ See the end of the section 'Demographic dynamics' for a chart of the death rate (per 100,000) of the Thirty Years' War compared to other armed conflicts between 1400 and 2000.

- ^ Garrard, Greg (2004). Ecocriticism. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 85–87. ISBN 9780415196925.

- ^ Garrard, Greg (2004). Ecocriticism. New York, New York: Routledge. pp. 93–104. ISBN 9780415196925.

- ^ Foust, Christina R.; O'Shannon Murphy, William (2009). "Revealing and Reframing Apocalyptic Tragedy in Global Warming Discourse". Environmental Communication. 3 (2): 151–167. Bibcode:2009Ecomm...3..151F. doi:10.1080/17524030902916624. S2CID 144658834.

- ^ Lovelock J (16 January 2006). "The Earth is about to catch a morbid fever that may last as long as 100,000 years". The Independent. Archived from the original on 8 April 2006. Retrieved 4 October 2007.

- ^ Jeffries S (15 March 2007). "We should be scared stiff". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Aitkenhead D (1 March 2008). "James Lovelock: 'Enjoy life while you can: in 20 years global warming will hit the fan'". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 July 2022. Retrieved 28 July 2022.

- ^ Johnston I (23 April 2012). "'Gaia' scientist James Lovelock: I was 'alarmist' about climate change". MSNBC. Archived from the original on 24 April 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ^ Miller, Laura (26 July 2017). "What Kind of Novel Do You Write When You Believe Civilization Is Doomed?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 23 May 2020.

'The Uninhabitable Earth,' the most-read story in New York magazine's history

- ^ Khanna, Parag (August 15, 2022). "What Comes After the Coming Climate Anarchy?". TIME. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Spratt, David; Dunlop, Ian T. (May 2019). "Existential climate-related security risk: A scenario approach". breakthroughonline.org.au. Breakthrough - National Centre for Climate Restoration.

- ^ Bendell, Jem (27 July 2018). "Deep adaptation: a map for navigating climate tragedy". Occasional Papers. 2. Ambleside, UK: University of Cumbria: 1–31.

- ^ Hunter, Jack (16 March 2020). "The 'climate doomers' preparing for society to fall apart". BBC News. Retrieved 8 October 2020.

- ^ "'High likelihood of human civilisation coming to end' by 2050, report finds". The Independent. 2019-06-04. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ Hollingsworth, Julia (4 June 2019). "Global warming could devastate civilization by 2050: report". CNN. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ Ahmed, Nahfeez (November 22, 2019). "The Collapse of Civilization May have Already Begun". VICE. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Best, Shivali (2019-06-05). "Human civilisation 'will collapse by 2050' if we don't tackle climate change". mirror. Retrieved 2019-12-21.

- ^ Bromwich, Jonah E. (26 December 2020). "The Darkest Timeline". The New York Times. Retrieved October 8, 2021.

- ^ Nicholas, Thomas; Hall, Galen; Schmidt, Colleen (14 July 2020). "The faulty science, doomism, and flawed conclusions of Deep Adaptation". openDemocracy. Retrieved 8 October 2021.

- ^ Wallace-Wells, David (October 26, 2022). "Beyond Catastrophe: A New Climate Reality Is Coming Into View". New York Times. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Paoletta, Kyle (April 2023). "The Incredible Disappearing Doomsday". Harper's Magazine. Retrieved 5 October 2023.

- ^ "Top climate scientists are sceptical that nations will rein in global warming". Nature. 1 November 2021. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021. Retrieved 4 October 2023.

- ^ Bradshaw, Corey J. A.; Ehrlich, Paul R.; Beattie, Andrew; Ceballos, Gerardo; Crist, Eileen; Diamond, Joan; Dirzo, Rodolfo; Ehrlich, Anne H.; Harte, John; Harte, Mary Ellen; Pyke, Graham; Raven, Peter H.; Ripple, William J.; Saltré, Frédérik; Turnbull, Christine; Wackernagel, Mathis; Blumstein, Daniel T. (2021). "Underestimating the Challenges of Avoiding a Ghastly Future". Frontiers in Conservation Science. 1. doi:10.3389/fcosc.2020.615419.

- ^ Weston, Phoebe (January 13, 2021). "Top Scientists Warn of 'Ghastly Future of Mass Extinction' and Climate Disruption". The Guardian. Retrieved February 13, 2021.

- ^ Pentin, Edward (June 19, 2015). "German Climatologist Refutes Claims He Promotes Population Control". National Catholic Register. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Adedokun, Naomi (October 19, 2019). "Andrew Neil dismantles Extinction Rebellion's claim that 'billions of children would die'". Daily Express. Retrieved January 20, 2023.

- ^ Kraus, Tina; Lee, Ian (3 August 2022). "Scientists say the world needs to think about a worst-case "climate endgame"". CBS News. Retrieved 11 August 2022.

- ^ Steel, Daniel; DesRoches, C. Tyler; Mintz-Woo, Kian (October 6, 2022). "Climate change and the threat to civilization". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (42): e2210525119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11910525S. doi:10.1073/pnas.2210525119. hdl:10468/13756.

- ^ Kelman, Ilan (October 10, 2022). "Connecting disciplines and decades". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (42): e2213953119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11913953K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2213953119. PMID 36215476.

- ^ Bhowmik, Avit; McCaffrey, Mark S.; Roon Varga, Juliette (November 2, 2022). "From Climate Endgame to Climate Long Game". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (45): e2214975119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11914975B. doi:10.1073/pnas.2214975119. PMC 9659379. PMID 36322727.

- ^ Ruhl, J. B.; Craig, Robin Kundis (November 29, 2022). "Designing extreme climate change scenarios for anticipatory governance". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (49): e2216155119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11916155R. doi:10.1073/pnas.2216155119. PMC 9894176. PMID 36445959.

- ^ Kemp, Luke; Xu, Chi; Depledge, Joanna; Ebi, Kristie L.; Gibbins, Goodwin; Kohler, Timothy A.; Rockström, Johan; Scheffer, Marten; Schellnhuber, Hans Joachim; Steffen, Will; Lenton, Timothy M. (October 10, 2022). "Reply to Burgess et al: Catastrophic climate risks are neglected, plausible, and safe to study". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 119 (42): e2214884119. Bibcode:2022PNAS..11914884K. doi:10.1073/pnas.2214884119. PMC 9586271. PMID 36215481.

Works cited[edit]

- Essential Visual History of the World. Washington, D.C.: National Geographic. 2007. ISBN 978-1-4262-0091-5. OCLC 144922970.