Seaman-Drake Arch

| Seaman-Drake Arch | |

|---|---|

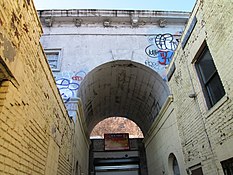

From the street. only the upper part of the arch can be seen over the commercial buildings that obscure it from full view (2015) | |

| General information | |

| Status | semi-abandoned, not landmarked |

| Address | 5065 Broadway at West 216th Street Inwood, Manhattan, New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°52′14″N 73°54′55″W / 40.87056°N 73.91528°W |

| Construction started | 1855 |

| Client | Seaman family |

| Height | 35 feet (10.67 m) |

| Dimensions | |

| Other dimensions | depth: 20 feet (6.10 m) width: 40 feet (12.19 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Material | Inwood marble |

The Seaman-Drake Arch, also known as the Inwood Arch, is a remnant of a hilltop estate built in 1855 in the Inwood neighborhood of Manhattan, New York City by the Seaman family. Located at 5065 Broadway at West 216th Street, the arch was built from Inwood marble quarried nearby. It is 35 feet (10.67 m) tall, 20 feet (6.10 m) deep, and 40 feet (12.19 m) wide, and was once the gateway to the estate.[1]

Today, the arch, which is said to be modeled on the Arc de Triomphe in Paris,[2] is partially obscured from view by low-rise commercial buildings, and has been tagged by graffitists; its soft marble facade is decaying.[1] The south side of the structure is used for storage by the transmission repair shop it is behind.[3]

History and description[edit]

The Seaman family, led by Captain John Seaman, emigrated from the United Kingdom and settled in what is now Hempstead on Long Island in 1647 or 1653.[1][2] The family eventually acquired 12,000 acres (4,900 ha) there.[4]

In 1851 John Ferris Seaman[5] and his brother Valentine – the sons of Dr. Valentine Seaman, who in the early 1800s was one of the men who brought Edward Jenner's smallpox vaccine to the United States[2][4] – bought 25 acres (10.12 ha)[2] of hilltop property in Upper Manhattan near Kingsbridge Road (now Broadway), between what would become West 214th and 218th Streets.[6] The site was about a half-mile north of the Dyckman homestead,[1] and the property ran down to Spuyten Duyvil Creek.[6] At the top of the hill, the Seamans built a marble mansion around 1855, apparently intending it as a country home, as the family had another residence in lower Manhattan.[1] The mansion originally featured a domed tower, but this was later converted into a square one.[4]

The arch was built from the same marble as the house, and stood at the beginning of a road which wound up and around the hill to the mansion. It originally had large iron gates, the pivots for which are still extant, and probably quarters inside for a gatekeeper. The arch has two niches intended for statues, which are now empty.[1]

The mansion house, sometimes referred to as the "Seaman Castle",[7] – and the estate as "Seaman's Folly"[8] – was principally occupied by John Ferris Seaman, a merchant, who married Ann Drake. Ferris died in 1872 and Ann in 1878, leaving no children.[5] Ann Drake Seaman willed the estate – "my marble house, grounds and outbuildings ... furniture and plate"[1] – to her nephew,[9] Lawrence Drake;[1] 145 relatives contested the will,[2] which was not settled until around 1893.[10]

By 1895,[7] the house had become the headquarters of the Suburban Riding and Driving Club, of which Lawrence Drake was a member.[1] The estate originally had a large marble stable, but additional stables and sheds were added for the use of the members' horses. The interior of the mansion was altered for its new role as a clubhouse, with bedrooms becoming private dining rooms, dining halls and parlors becoming a café and reception area, and the house's conservatory becoming a smoking and sun room. The club spent more than $10,000 in the conversion from residence to clubhouse.[7] The club would undoubtedly have found the mansion's location convenient, as it was near the Harlem Speedway, which was built in 1894-98 from West 155th Street to Dyckman Street for the exclusive use of horse-drawn carriages and horseback riders.[11][12]

In 1905, the house was sold to Thomas Dwyer, who lived in the mansion and used the quarters in the arch for his business,[1] which he christened the Marble Arch Company.[2] Dwyer was a contractor, and is known for having built the Soldiers' and Sailors' Monument and part of the Metropolitan Museum of Art.[1]

Dwyer sold the Seaman-Drake estate in 1938 for the development of a five-building apartment complex.[1] The 400-unit[13] Park Terrace Gardens on Park Terrace East and West between West 215th and 217th Streets stands on the plot where the mansion was once located.[7] The arch was not part of the sale, and by that time, in fact as early as 1912, low brick buildings had sprung up around the arch – some of them car dealerships which used the archway as an entrance. Since the 1960s, the arch has been part of an auto-body shop.[1]

A fire in 1970 seriously damaged the structure of the arch, and left it roofless and open to the elements; one can see into the arch from higher buildings on either side.[1] Inside, the marble walls, which are covered with vines of ivy, block out most of the ambient city noise, creating a "tranquil retreat".[14]

Rental and preservation[edit]

There was an effort made in 2003 to provide some legal protection for the arch by landmarking it, which received support from New York City Councilman Robert Jackson, but the campaign never came to fruition.[15]

In 2009, the commercial property that the arch is a part of was listed for rent at $17,000 a month for about 7,000 square feet (650 m2). The owner explained that he did not want to sell it because he inherited it from his father, who was given the property, including the Seaman-Drake Arch, by a man whose life he saved in World War II. One potential buyer was interested in turning the buildings into a nightclub,[3] while others sought the property for a catering firm and a hair salon.[16] By 2014, the auto body shop that had been renting the space had been evicted, and the property was again listed for rent, this time at $17,500. Potential renters had expressed interest in using it for a bowling alley or, again, a nightclub. The owner of the property expressed a commitment to not raze the arch, saying "Nobody will take the arch down ever."[17]

As of 2015, the commercial property remains a transmission repair shop and an auto body shop; the Seaman-Drake Arch has not been landmarked by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission, and it is not listed on the National Register of Historic Places.[3][18]

In 1988, Christopher Gray of The New York Times said about the arch:

The marble is decaying, depositing small piles of silvery grains where water drips, and the entire structure is as worn as the steps of an ancient cathedral. ... There is not much real estate development in Inwood, and nothing left to burn inside the arch itself; the main threat to the arch's survival seems to be New York's acidic atmosphere and rain. Until it falls or is taken down, the venerable Seaman-Drake Arch will probably continue to serve as a gateway, though of a quite different sort than that originally imagined.[1]

Gallery[edit]

-

The Seaman-Drake mansion in 1896, when it had become the clubhouse of the Suburban Riding and Driving Club

-

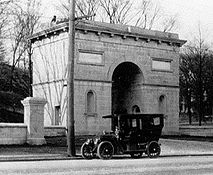

The arch in 1910

-

The arch as seen from across the street

(2015) -

The arch as seen from below

(2015)

See also[edit]

- List of New York City Designated Landmarks in Manhattan above 110th Street

- National Register of Historic Places listings in Manhattan above 110th Street

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Gray, Christopher "Streetscapes: Seaman-Drake Arch; Encrusted Relic of a Mid-19th-Century Inwood Estate" The New York Times (June 5, 1988)

- ^ a b c d e f Thompson, Cole. "The Old Seaman Mansion" My Inwood

- ^ a b c "19th Century Marble Arch for Rent in Inwood, Needs a Little TLC" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine DNAinfo (October 14, 2009)

- ^ a b c Renner, James. "Seaman-Drake Arch" Hudson Heights Owners Coalition website

- ^ a b "John Ferris Seaman"

- ^ a b "Inwood, Manhattan" Forgotten NY (January 31, 2010)

- ^ a b c d Thompson, Cole. "The Inwood Arch and Mansion: Circa 1896" My Inwood

- ^ Thompson, Cole. "Seaman-Drake Arch" My Inwood

- ^ The relationship between Lawrence and Ann Drake is not clear; he may have been a second cousin. See "Ann Drake"

- ^ "Ann Drake"

- ^ Robinson, Lauren. "How Harlem River Speedway Became Harlem River Drive" Museum of the City of New York (February 28, 2012)

- ^ "Harlem River Drive: An Historic Overview". NYCRoads.com.

- ^ Alberts, Hana R. "Why a 19th-Century Marble Arch Sits Inside an NYC Auto Shop" Curbed (June 4, 2013)

- ^ Carr, Nick. "How A Beautiful 19th-Century Marble Archway In Manhattan Became An Auto Body Shop" Scouting New York (June 4, 2013)

- ^ Wagner, Lindsay. "Inwood Residents Push for Preservation" The Uptowner (November 17, 2011)

- ^ Carlson, Jen. "Historic Arch for Rent in Inwood" Archived 2016-07-13 at the Wayback Machine Gothamist (November 11, 2009)

- ^ Chiwaya, Nigel. "Nightclub, Bowling Alley in Talks to Rent Historic Inwood Arch, Broker Says" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine DNAinfo (June 17, 2014)

- ^ Zanoni, Carla. "Inwood Chosen as One of Six Neighborhoods That Deserve Historic Preservation" Archived 2015-04-02 at the Wayback Machine DNAinfo (December 29, 2010) Quote: "Volunteers for Isham Park, a local Inwood preservation group, which will work with HDC in the coming year to identify neighborhood landmarks to propose for the landmarking, which will likely include historic sites surrounding the Park Terrace area of Inwood, including Isham Park and the Seaman-Drake arch."

External links[edit]

- Contemporary and historical images

- 1924 aerial photograph, shows the Seaman-Drew Mansion, but within the Inwood street grid