LGBTQ culture in Leeds

| Part of a series on |

| LGBTQ rights in the United Kingdom |

|---|

|

| By location |

| Policy aspects |

| Legislation |

| Culture |

| Organisations |

| History |

LGBT culture in Leeds, England, involves an active community of people who identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender/transsexual. A BBC News Online article published in 2012 stated that, while Leeds City Council has not published statistics relating to the number of LGBT residents, the figure can be estimated at 10% of the overall population,[1] which currently suggests a total of at least 77,000. The tenth year of the Leeds Pride march and celebration, held in 2016, was attended by over 40,000 people.[2]

History

[edit]A comprehensive social history of LGBT communities and culture in Leeds has yet to be compiled, and this was an aim of the Queer Stories project, a partnership between Yorkshire MESMAC, Leeds Museums and Galleries, and the West Yorkshire Archive Service.[3] An awareness-raising exhibition curated by the project group was hosted at Leeds City Museum between November 2015 and May 2016,[4] and included a mixture of objects and testimonies.[5]

With funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund, the project grew into West Yorkshire Queer Stories, which went on to collect 200 oral history interviews from LGBT people in the region between 2018 and 2020. These are available on the project's website.[6]

Pre-1970

[edit]Pubs and bars catering to LGBT customers have traditionally centred around The Calls and Lower Briggate, an area sometimes referred to as Leeds Gay Quarter, #gayleeds, Leeds' gay village[7] or Freedom Quarter.[8] In the 1930s, the Pelican Social Club in Blayd’s Yard, off Lower Briggate, was reportedly "frequented by effeminate men who called each other by female Christian names and two of whom wore women’s clothing".[9] The Mitre pub on Commercial Street (formerly the Horse and Jockey, dating back to 1744)[10] welcomed gay male customers in the evenings throughout the 1950s, and was also regularly visited by sympathetic police officers before closing in 1961.[11] The Royal Hotel, off Lower Briggate, was another gay-friendly venue during the 1960s.[12]

The city's longest-running gay pub is The New Penny, formerly known as the Hope and Anchor, which has "provided a safe venue for the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Trans* community" since 1953, according to the blue plaque placed there by Leeds Civic Trust in 2016.[13] In March 1968, following the UK's decriminalisation of homosexual acts, the Hope and Anchor was featured in an exposé-style article in the local Union News,[14] which paid particular attention to the behaviour and habits of its gay clientele:

Around the room, men sit cuddling and kissing, or are dancing clumsily together, as they hug each other tightly. Others walk around greeting friends who have just arrived, always touching their bodies and sometimes picking one another up.

The piece also described Saturday as "the big night of the week" and reported that couples tended to move on to coffee bars after the pub's closing time, where they would remain until around 1 a.m.[14]

The pub was targeted and "completely wrecked" by football fans following the Leeds United v. Glasgow Rangers match at Elland Road on 9 April 1968.[15] A period of closure followed, after which it reopened as The New Penny.[16]

1970s-1990s

[edit]The activities of Leeds-based gay rights organisations have been reported in newspapers as far back as 1971.[17] The University of Leeds branch of the national Gay Liberation Front, known as the Gay Liberation Society, distributed leaflets at events saying "there is nothing wrong in loving people of the same sex".[18] The group was also photographed demonstrating in solidarity with the people of Northern Ireland, following the events of Bloody Sunday (1972).[19] Its headquarters, which opened on Woodhouse Lane in December 1972, were ransacked within weeks: a member reported to the Yorkshire Evening Post that a window was smashed, books were ripped, and decorations torn down.[20] While the wider Gay Liberation Front movement disbanded in 1974, the Leeds society continued for several more years.[21]

Existing gay pubs remained in business throughout the 1970s, while the White Hart in nearby Pool-in-Wharfedale offered a countryside escape for older gay men seeking meals and companionship on Sunday afternoons and evenings.[12]

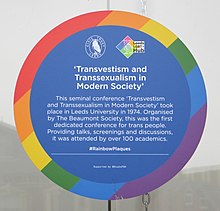

In March 1974, the University of Leeds hosted what was billed as the country's first national conference for transvestite and transsexual people.[22] Titled Transvestism and Transsexualism in Modern Society, it attracted 102 attendees and included talks and a screening of the 1968 documentary The Queen, filmed on New York's underground drag scene.[22]

A young records clerk at Leeds General Infirmary, Paul Furness, first brought the World Health Organization's classification of homosexuality as a disease to the attention of Tom Robinson of the Tom Robinson Band in 1978. The singer made many references to this fact during concerts and included the classification number 302.0 on the sleeve of the Rising Free EP, which included the song "Glad to Be Gay".[23]

Gay women received support from the Leeds Lesbian Line, a telephone switchboard that opened in May 1982. By the time of its first anniversary, it was being staffed by six women and was available for two hours on Tuesday evenings, receiving on average six calls a night.[24]

The 1980s saw a proliferation of LGBT-friendly pubs and nightclubs in Leeds,[12] including The Bridge Inn (on Bridge End); Ye Old Red Lion (at the corner of Meadow Lane/Hunslet Road); Charlie's Club and Bananas Bar (in Lambert's Yard/Queens Court); and Rockshots 2 (on Lower Briggate). These were joined in the 1990s by Primo's and Primo's II (New York Street/Back New York Street); Queens Court, which replaced Charlie's Club; Bar Fibre (Lower Briggate); and Blayd's Bar (in Blayds Yard), which was popular with lesbians.[12]

Gay-friendly club nights also became popular in the 1990s. Running from 1993 to 1996, Vague was a "mixed" (i.e. gay and straight) night at Leeds nightclub The Warehouse.[25] It was followed by SpeedQueen, which began at The Warehouse, before moving to Stinky's Peephouse,[26] where its Saturday night gatherings attracted 350 clubbers each week and featured an outdoor terrace and giant bed.[26] In 2003, SpeedQueen returned to The Warehouse,[27] but moved again to Gatecrasher,[28] and to Mint Warehouse in 2016.[29] Both Vague and SpeedQueen "blended a kitsch theme with an artistic underbelly which saw clubbers return to some of the outlandish costumes which characterised the late 70s", according to Yorkshire Evening Post journalist Rod McPhee.[30]

Post-2000

[edit]Leeds saw one of the country's very first civil partnerships, which took place at 8 a.m. on 21 December 2005, between entrepreneur Terry George and Michael Rothwell. The couple signed the register at Bar Fibre on Lower Briggate after being granted a special licence.[31]

The first Leeds Gay Pride was held on 6 August 2006, and saw a parade and open-topped pink bus make their way through the streets of the city centre.[32] Taking place every year since, the event has grown to involve many local businesses and increasing numbers of attendees, reported at over 40,000 in 2016.[33] In the same year, its contribution to the city's economy was calculated at over £3 million.[34]

LGBT students at the city's universities continue to be politically active. In March 2017, they rallied in Victoria Gardens against gay concentration camps in Chechnya.[35]

Female students organized a "women-centric queer dance party" called Scissors at Leeds University Union in January 2017.[36] The publicity stated: "It’s no secret that too often the LGBTQ+ scene focuses on white, gay, slim, and able-bodied men; we aim to offset this balance creating a space where everyone can feel free to be themselves and dance."[36]

On 26 September 2018, The Hyde Park Book Club, a venue in Hyde Park, Leeds, held an event called LGBTQ The Music 2, presented by Come Play With Me,[37] celebrating LGBTQ+ people in music.[38]

In January 2019, Leeds-based brewery Anthology created a new beer to celebrate LGBT History Month, with 10p from every pint donated to Stonewall.[39]

Leeds Freedom Bridge

[edit]

Plans to repaint the railway bridge over Lower Briggate in rainbow colours, reflecting the design of the LGBT pride flag, were announced in September 2016 by LGBT activist and Leeds campaigner Thomas Wales after the project had remained in the LGBT political wilderness for years.[40] Work was completed by Network Rail in February 2017 and Councillor Jonathan Pryor said, "This bridge represents a tremendous show of support for the city’s LGBT community. Not only will the Leeds Freedom Bridge be an eye-catching addition ... it will also make a huge statement to our many visitors. We embrace and celebrate diversity and the contribution it makes to ensuring Leeds is such a warm, welcoming and successful city".[41]

The term Freedom Bridge was coined by fellow LGBT campaigner and community website editor Ross McCusker who took inspiration from San Francisco artist Gilbert Baker's Freedom Flag.

Recreation

[edit]The tourist information service Visit Leeds promotes LGBT tourism, including nightlife, and produces a Leeds LGBT* Map. Among the LGBT-friendly venues it lists in the city centre are The Viaduct Showbar, The New Penny, Blayd’s Bar, Wharf Chambers, Tunnel, The Bridge, Queens Court and Bar Fibre. The latter two co-host popular Bank Holiday 'Courtyard Parties' during the summer.[42]

LGBT-inclusive sports clubs are numerous in Leeds.[43] The athletics club Leeds FrontRunners describes itself as "an all-inclusive club, welcoming anyone who identifies as LGBT*, their friends and even people who just love running and are happy to look beyond labels".[44] The Yorkshire Terriers Football Club was one of the first gay-friendly teams to be established in the UK.[45] Leeds Hunters Rugby is an inclusive rugby club which aims to provide a safe environment for any adult male to play Rugby Union irrespective of race, sexual orientation, ethnicity and level of fitness or experience, and any person over the age of 18 to access touch rugby. The club was established in 2016 and train in North Leeds.[46] Marching Out Together is the Leeds United FC supporters group for LGBTQ fans; they were officially endorsed by the club in 2017.[47][48]

Leeds has its own Queer Film Festival, which first took place in 2005, then 2010, and annually since 2013. As well as screening films such as The Watermelon Woman and Set It Off, the event has included talks, zine-making and letter-writing workshops.[49]

The gay lifestyle magazine Bent was published in Leeds.[50]

The LGBT community website #gayyorkshire is based in Leeds and helps to promote the Leeds LGBT night-time economy, organisations and events as well as providing other LGBT information from across the wider county of Yorkshire.[citation needed]

Notable LGBT people from Leeds

[edit]- Nicola Adams, professional boxer.[51]

- Marc Almond, vocalist of Soft Cell.[52]

- Alan Bennett, writer and actor.[53]

- Jack Birkett, dancer and performer.[54]

- Thomas Wales, LGBT activist and Leeds Freedom Bridge campaigner.[55]

- Terry George, entrepreneur.[56]

- Robert Hawthorn Kitson, artist.[57]

- Cyril Livingstone, theatre actor, director, critic and couturier, commemorated in a Rainbow Plaque[58]

- Mark Michalowski, author and founder of Shout! magazine.[59]

- Angela Morley, composer and conductor.[60]

- Anthony Morley, the first Mr Gay UK and a convicted murderer.[61]

- John Riley (poet)

- Sophie Wilson, computer scientist.[62]

LGBT links with Leeds

[edit]The banker and MP Ernest Beckett, 2nd Baron Grimthorpe, who resided at Kirkstall Grange, Headingley, in the latter half of the nineteenth century, is believed to have been the father of Violet Trefusis, who is remembered for a same-sex affair with the poet Vita Sackville-West. Their relationship was documented in a series of passionate letters between 1912 and 1922.[63]

References

[edit]- ^ "Leeds gay quarter proposals examined by council". BBC News. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Leeds LGBT 2016 Impact Survey". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "West Yorkshire Queer Stories". West Yorkshire Queer Stories - About Us. Retrieved 20 April 2023.

- ^ "Leeds City Museum hosts new exhibition Leeds Queer Stories". Leeds City Council website. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ FiliptheFlea. "Queer Stories: Leeds LGBT*IQ Social History Project". Yarn Community. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Welcome to West Yorkshire Queer Stories". West Yorkshire Queer Stories. West Yorkshire Archive Service. Retrieved 10 July 2020.

- ^ "Visit Leeds: LGBT*". Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "About Freedom Quarter". Freedom Quarter. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "The Piquant Past", Yorkshire Evening Post, 4 March 1985.

- ^ "Horse and Jockey Hotel, number 48 Commercial Street". Leodis: A Photographic Archive of Leeds. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ cobbydaler. "Mitre Pub". Secret Leeds. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ a b c d "Gay bars". Secret Leeds. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "New Penny Blue Plaque". Retrieved 17 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b Dalton, John (8 March 1968). "The Ones in Twenty". Union News.

- ^ Edwards, Gary (2003). Paint it white : following Leeds everywhere. Edinburgh: Mainstream. ISBN 1840187298.

- ^ Trojan. "Pubs worth celebrating". Secret Leeds. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Davison, Colin (23 March 1971). "Liberating the Gay". Yorkshire Evening Post.

- ^ "Boy (12) handed 'gay' leaflets". Yorkshire Evening Post. 1 November 1971.

- ^ "Solidarity March, The Headrow". Leodis: A Photographic Archive of Leeds. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Gay Lib HQ ransacked". Yorkshire Evening Post. 17 December 1972.

- ^ "Gay Liberation Front". LGBT Archive. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ a b Elkins, Richard; King, Dave (Autumn 2007). "The First UK Transgender Conferences, 1974 and 1975". GENDYS Journal (39). Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Furness, Paul; Woods, Jude; Marek, Romaniszyn. "302.0: Glad to Be Gay". Queer Beyond London. Retrieved 15 July 2017.

- ^ Wark, Penny (2 May 1983). "Crossing the Line". Yorkshire Post.

- ^ Collard, James (23 October 2011). "United Kingdom of Dance". 20 October 1994. The Daily Telegraph Newspaper. Retrieved 5 June 2014.

- ^ a b Tiley, Zenobia. "Speedqueen". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ Tiley, Zenobia. "Speedqueen comes home". BBC.co.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ McPhee, Rod. "The faces of modern Leeds". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "SpeedQueen Party at Mint Warehouse". Leeds City Magazine. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ McPhee, Rod. "The Warehouse: Leeds nightclub memories". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- ^ "History made as Yorkshire gay couple tie the knot". The Yorkshire Post. Retrieved 18 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ "Leeds Pride 2006, Photographs, Leeds, United Kingdom". Leeds-uk.com. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Leeds LGBT 2016 Impact Survey". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Leeds LGBT 2016 Impact Survey". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Students organise Leeds rally against Chechnyan 'gay prison camps'". The Gryphon. Leeds University Union. 12 April 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b "Scissors – LUU hosts first women-centred LGBTQ+ club night". The Gryphon. Leeds University Union. February 2017. Archived from the original on 7 December 2021. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "DEBBIE GOOGE HELPS LAUNCH LGBTQ THE MUSIC 2". M Magazine. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "LGBTQ The Music 2". Hyde Park Book Club. Retrieved 27 February 2019.

- ^ "History Month Pale". Untappd. Untappd, Inc. Retrieved 1 March 2019.

- ^ Newton, Grace. "Leeds Railway Bridge Gets Landmark Paint Job". Yorkshire Evening Post. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ Besanvalle, James (18 February 2017). "Leeds hopes to bridge equality with new rainbow building". Gay Star News. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Visit Leeds: LGBT*". Visit Leeds. Archived from the original on 23 January 2018. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "LGBT Sports Clubs". Active Leeds. Leeds City Council. Archived from the original on 19 July 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Leeds FrontRunners". Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Our Story". Yorkshire Terriers FC. Archived from the original on 22 October 2017. Retrieved 18 June 2017.

- ^ "Who are Leeds Hunters". Leeds Hunters Rugby. Retrieved 15 March 2022.

- ^ "A message from the board of Marching Out Together". www.leedsunited.com. 29 November 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Marching Out Together: England's newest LGBT supporters' club at Leeds United". Sky Sports. Retrieved 25 November 2022.

- ^ "Leeds Queer Film Festival website: History". Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Bent magazine website

- ^ Khaleeli, Homa (9 August 2014). "Nicola Adams: 'It always felt like boxing was my path'". The Guardian. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ Almond, M., Tainted Life – the autobiography, Sidgwick and Jackson, 1999, p122

- ^ "Inside Bennett's fridge". The Telegraph. 30 October 2004. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ^ "Jack Birkett obituary". The Guardian. 28 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 April 2023.

- ^ "Leeds Freedom Bridge project completed". Retrieved 21 November 2018.

- ^ Rosalind, Renshaw. "Good times, tough times". thetimes.co.uk. Retrieved 12 August 2015.

- ^ Leslie, Charles. "A Memory of Taormina". leslielohman.org. Archived from the original on 11 June 2017. Retrieved 6 July 2017.

- ^ Johnson, Kristian (3 August 2018). "Rainbow Plaque Trail unveiled ahead of Leeds Pride 2018". leedslive. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- ^ Michalowski, Mark. "About Me". Across the Maps of Heaven. Blogspot. Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "Musical Variations: The Life of Angela Morley". BBC. Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- ^ "Cannibal chef jailed for 30 years". CNN.com. 20 October 2008. Archived from the original on 23 October 2008. Retrieved 21 October 2008.

- ^ Bagulay, Richard (8 May 2018). "Sophie Wilson: ARM and How Making Things Simpler Made Them Faster & More Efficient". Hackaday. Hackaday.com. Retrieved 23 June 2018.

- ^ Leaska, edited by Mitchell A.; Leaska, John Phillips; with an introduction by Mitchell A. (1991). Violet to Vita : the letters of Violet Trefusis to Vita Sackville-West, 1910-21. New York, N.Y., USA: Penguin Books. ISBN 0140157964.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help)CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)