Cleveland Street scandal

The Cleveland Street scandal occurred in 1889, when a homosexual male brothel and house of assignation on Cleveland Street, London, was discovered by police. The government was accused of covering up the scandal to protect the names of aristocratic and other prominent patrons.

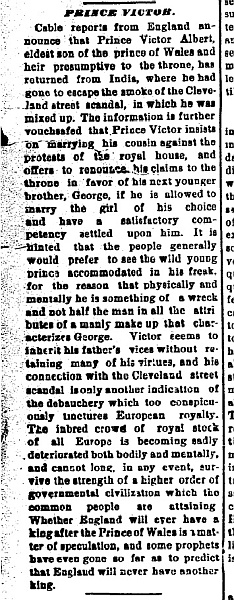

At the time, sexual acts between men were illegal in Britain, and the brothel's clients faced possible prosecution and absolute social rejection if discovered. It was rumoured that Prince Albert Victor, the eldest son of the Prince of Wales and second-in-line to the British throne, had visited the brothel, though this has never been substantiated. Unlike overseas newspapers, the British press never named Albert Victor, but the allegation influenced the handling of the case by the authorities[1] and has coloured biographers' perceptions of him since.

The police acquired testimonies that Lord Arthur Somerset, an equerry to the Prince of Wales, was a patron.[2] Both he and the brothel keeper, Charles Hammond, managed to flee abroad before a prosecution could be brought. The male prostitutes, who also worked as telegraph messenger boys for the General Post Office, were given light sentences and no clients were prosecuted. After Henry James FitzRoy, Earl of Euston, was named in the press as a client, he successfully sued for libel. The scandal fuelled the attitude that male homosexuality was an aristocratic vice that corrupted lower-class youths. Such perceptions were still prevalent in 1895 when the Marquess of Queensberry accused Oscar Wilde of posing as a sodomite.

Male brothel[edit]

In July 1889, Police Constable Luke Hanks was investigating a theft from the London Central Telegraph Office. During the investigation, a fifteen-year-old telegraph boy named Charles Thomas Swinscow was discovered to be in possession of fourteen shillings, equivalent to several weeks of his wages. At the time, messenger boys were not permitted to carry any personal cash in the course of their duties, to prevent their own money being mixed with that of the customers. Suspecting the boy's involvement in the theft, Constable Hanks brought him in for questioning. After hesitating, Swinscow admitted that he earned the money working as a prostitute for a man named Charles Hammond, who operated a male brothel at 19 Cleveland Street. According to Swinscow, he was introduced to Hammond by a General Post Office clerk, eighteen-year-old Henry Newlove. In addition, he named two seventeen-year-old telegraph boys who also worked for Hammond: George Alma Wright and Charles Ernest Thickbroom. Constable Hanks obtained corroborating statements from Wright and Thickbroom and, armed with these, a confession from Newlove.[3]

Constable Hanks reported the matter to his superiors and the case was given to Detective Inspector Frederick Abberline. Inspector Abberline went to the brothel on 6 July with a warrant to arrest Hammond and Newlove for violation of Section 11 of the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. The Act made all homosexual acts between men, as well as procurement or attempted procurement of such acts, punishable by up to two years' imprisonment with or without hard labour. He found the house locked and Hammond gone, but Abberline was able to apprehend Newlove at his mother's house in Camden Town.[4] In the time between his statement to Hanks and his arrest, Newlove had gone to Cleveland Street and warned Hammond, who had consequently escaped to his brother's house in Gravesend.[5]

Notable clients[edit]

On the way to the police station, Newlove named Lord Arthur Somerset and Henry FitzRoy, Earl of Euston, as well as a British Army colonel by the name of Jervois, as visitors to Cleveland Street.[6] Somerset was the head of the Prince of Wales's stables. Although Somerset was interviewed by police, no immediate action was taken against him, and the authorities were slow to act on the allegations of Somerset's involvement.[7] A watch was placed on the now-empty house and details of the case shuffled between government departments.[8]

On 19 August, an arrest warrant was issued in the name of George Veck, an acquaintance of Hammond's who pretended to be a clergyman. Veck had actually worked at the Telegraph Office, but had been sacked for "improper conduct" with the messenger boys.[9] A seventeen-year-old youth found in Veck's London lodgings revealed to the police that Veck had gone to Portsmouth and was returning shortly by train. The police arrested Veck at London Waterloo railway station. In his pockets they discovered letters from Algernon Allies. Abberline sent Constable Hanks to interview Allies at his parents' home in Sudbury, Suffolk. Allies admitted to receiving money from Somerset, having a sexual relationship with him, and working at Cleveland Street for Hammond.[10] On 22 August, police interviewed Somerset for a second time, after which Somerset left for Bad Homburg,[11] where the Prince of Wales was taking his summer holiday.[12]

On 11 September, Newlove and Veck were committed for trial. Their defence was handled by Somerset's solicitor, Arthur Newton, with Willie Mathews appearing for Newlove, and Charles Gill for Veck. Somerset paid the legal fees.[13] By this time, Somerset had moved on to Hanover, to inspect some horses for the Prince of Wales, and the press was referring to "noble lords" implicated in the trial.[14] Newlove and Veck pleaded guilty to indecency on 18 September and the judge, Sir Thomas Chambers, a former Liberal Member of Parliament who had a reputation for leniency, sentenced them to four and nine months' hard labour respectively.[15] The boys were also given sentences that were considered at the time to be very lenient.[16] Hammond escaped to France, but the French authorities expelled him after pressure from the British. Hammond moved on to Belgium from where he emigrated to the United States. Newton, acting for Somerset, paid for Hammond's passage.[17] On the advice of the Prime Minister, Lord Salisbury, no extradition proceedings were attempted, and the case against Hammond was quietly dropped.[18]

Somerset returned to Britain in late September to attend horse sales at Newmarket but suddenly left for Dieppe on 26 September, probably after being told by Newton that he was in danger of being arrested.[19] He returned again on 30 September. A few days later, his grandmother, Emily Somerset, Dowager Duchess of Beaufort, died and he attended her funeral.[20] The Hon. Hamilton Cuffe, Assistant Treasury Solicitor, and James Monro, Commissioner of Police, pressed for action to be taken against Somerset, but the Lord Chancellor, Lord Halsbury, blocked any prosecution.[21] Rumours of Somerset's involvement were circulating, and on 19 October Somerset fled back to France. Lord Salisbury was later accused of warning Somerset through Sir Dighton Probyn, who had met Lord Salisbury the evening before, that a warrant for his arrest was imminent.[22] This was denied by Lord Salisbury[23] and the Attorney General, Sir Richard Webster.[24] Probyn's informant may have been the Assistant Commissioner of Police, Richard Pearson.[25] The Prince of Wales wrote to Lord Salisbury, expressing satisfaction that Somerset had been allowed to leave the country and asking that if Somerset should "ever dare to show his face in England again", he would remain unmolested by the authorities,[26] but Lord Salisbury was also being pressured by the police to prosecute Somerset. On 12 November, a warrant for Somerset's arrest was finally issued.[27] By this time, Somerset was already safely abroad, and the warrant caught little public attention.[28] After an unsuccessful search for employment in Turkey and Austria-Hungary, Somerset settled down to live anonymously in France, at first in Paris then in Hyères on the French Riviera.[29] Other names mentioned by the press were Lord Ronald Gower and Lord Errol.[30] Also implicated was the prominent social figure Alexander Meyrick Broadley,[31][32] who fled abroad for four years.[33][34] The Paris Figaro even alleged that Broadley took General Georges Boulanger and Henri Rochefort to the house.[35] The allegation against Boulanger was later challenged by his supporters.[36] In December 1889 it was reported that both the Prince and Princess of Wales were being "daily assailed with anonymous letters of the most outrageous character" bearing upon the scandal.[37] By January 1890 sixty suspects had been identified, twenty-two of whom had fled the country.[38]

Public revelations[edit]

Because the press initially barely covered the story, the affair would have faded quickly from public memory if not for journalist Ernest Parke. The editor of the obscure politically radical weekly The North London Press, Parke got wind of the affair when one of his reporters brought him the story of Newlove's conviction. Parke began to question why the prostitutes had been given such light sentences relative to their offence (the usual penalty for "gross indecency" was two years) and how Hammond had been able to evade arrest. His curiosity aroused, Parke found out that the boys had named prominent aristocrats. He subsequently ran a story on 28 September hinting at their involvement but without detailing specific names.[39] It was only on 16 November that he published a follow-up story specifically naming Henry Fitzroy, Earl of Euston, in "an indescribably loathsome scandal in Cleveland Street".[40] He further alleged that Euston may have gone to Peru and that he had been allowed to escape to cover up the involvement of a more highly placed person,[41] who was not named but was believed by some to be Prince Albert Victor, the son of the Prince of Wales.[42]

Euston was in fact still in England and immediately filed a case against Parke for libel. At the trial, Euston admitted that when walking along Piccadilly a tout had given him a card which read "Poses plastiques. C. Hammond, 19 Cleveland Street". Euston testified that he went to the house believing Poses plastiques meant a display of female nudes. He paid a sovereign to get in but upon entering Euston said he was appalled to discover the "improper" nature of the place and immediately left. The defence witnesses contradicted each other, and could not describe Euston accurately.[43] The final defence witness, John Saul, was a male prostitute who had earlier been involved in a homosexual scandal at Dublin Castle, and featured in a clandestinely published erotic novel The Sins of the Cities of the Plain which was cast as his autobiography.[44] Delivering his testimony in a manner described as "brazen effrontery", Saul admitted to earning his living by leading an "immoral life" and "practising criminality", and detailed his alleged sexual encounters with Euston at the house.[45] The defence did not call either Newlove or Veck as witnesses, and could not produce any evidence that Euston had left the country. On 16 January 1890, the jury found Parke guilty and the judge sentenced him to twelve months in prison.[46] One historian considers Euston was telling the truth and only visited Cleveland Street once because he was misled by the card.[47] However, another has alleged Euston was a well-known figure in the homosexual underworld, and was extorted so often by the notorious blackmailer Robert Cliburn, that Oscar Wilde had quipped Cliburn deserved the Victoria Cross for his tenacity.[48] Saul stated that he told the police his story in August, which provoked the judge to enquire rhetorically why the authorities had not taken action.[49]

The judge, Sir Henry Hawkins, had a distinguished career, although after his death a former Solicitor General for England and Wales, Sir Edward Clarke, wrote: "Sir Henry Hawkins was the worst judge I ever knew or heard of. He had no notion whatever of what justice meant, or of the obligations of truth or fairness."[50] The prosecuting counsels, Charles Russell and Willie Mathews, went on to become Lord Chief Justice and Director of Public Prosecutions, respectively. The defence counsel, Frank Lockwood, later became Solicitor General, and he was assisted by H. H. Asquith, who became Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twenty years later.[51]

While Parke's conviction cleared Euston, another trial began on 16 December 1889 when Newlove's and Somerset's solicitor, Arthur Newton, was charged with obstruction of justice. It was alleged that he conspired to prevent Hammond and the boys from testifying by offering or giving them passage and money to go abroad. Newton was defended by Charles Russell, who had prosecuted Ernest Parke, and the prosecutor was Sir Richard Webster, the Attorney General. Newton pleaded guilty to one of the six charges against him, claiming that he had assisted Hammond to flee merely to protect his clients, who were not at that time charged with any offence or under arrest, from potential blackmail. The Attorney General accepted Newton's pleas and did not present any evidence on the other five charges.[52] On 20 May, the judge, Sir Lewis Cave, sentenced Newton to six weeks in prison,[53] which was widely considered by members of the legal profession to be harsh. A petition signed by 250 London law firms was sent to the Home Secretary, Henry Matthews, protesting at Newton's treatment.[54]

During Newton's trial, a motion in Parliament sought to investigate Parke's allegations of a cover-up. Henry Labouchère, a Member of Parliament from the Radical wing of the Liberal Party, was staunchly against homosexuality and had campaigned successfully to add the "gross indecency" amendment (known as the "Labouchère Amendment") to the Criminal Law Amendment Act 1885. He was convinced that the conspiracy to cover up the scandal went further up the government than assumed. Labouchère made his suspicions known in Parliament on 28 February 1890. He denied that "a gentleman of very high position"—presumably Prince Albert Victor—was in any way involved with the scandal, but accused the government of conspiracy to pervert the course of justice. He suggested that the Prime Minister Lord Salisbury and other officials colluded to hamper the investigation,[55] allowing Somerset and Hammond to escape, delaying the trials and failing to prosecute the case with vigour. Labouchère's accusations were rebutted by the Attorney General, Sir Richard Webster, who was also the prosecutor in the Newton case. Charles Russell, who had prosecuted Parke and was defending Newton, sat on the Liberal benches with Labouchère but refused to be drawn into the debate. After an often passionate debate over seven hours, during which Labouchère was expelled from Parliament after saying "I do not believe Lord Salisbury" and refusing to withdraw his remark, the motion was defeated by a wide margin, 206–66.[56] In a subsequent speech to the House of Lords, Salisbury bore witness against himself by suggesting his memory of his handling of the affair was defective.[55]

Aftermath[edit]

Public interest in the scandal eventually faded. Nevertheless, newspaper coverage reinforced negative attitudes about male homosexuality as an aristocratic vice, presenting the telegraph boys as corrupted and exploited by members of the upper class. That attitude reached its climax a few years later when Oscar Wilde was tried for gross indecency as the result of his affair with Lord Alfred Douglas.

Oscar Wilde may have alluded to the scandal in The Picture of Dorian Gray, first published in 1890.[57] Reviews of the novel were hostile. In a clear reference to the Cleveland Street scandal, one reviewer called it suitable for "none but outlawed noblemen and perverted telegraph boys".[58][59][60] Wilde's 1891 revision of the novel omitted certain key passages, which were considered too homoerotic.[60][61] In 1895, Wilde unsuccessfully sued Lord Alfred's father, the Marquess of Queensberry, for libel. Sir Edward Carson, Lord Queensberry's counsel, used quotes from the novel against Wilde and questioned him about his associations with young working men.[62] After the failure of his suit, Wilde was charged with gross indecency, found guilty, and subsequently sentenced to two years' hard labour. He was prosecuted by Charles Gill, who had defended Veck in the Cleveland Street case.[63]

Prince Albert Victor died in 1892, but society gossip about his sex life continued. Sixty years after the scandal, the official biographer of King George V, Harold Nicolson, was told by Lord Goddard, who was a twelve-year-old schoolboy at the time of the scandal, that Prince Albert Victor "had been involved in a male brothel scene, and that a solicitor had to commit perjury to clear him. The solicitor was struck off the rolls for his offence, but was thereafter reinstated."[64] In fact, none of the lawyers involved in the case was convicted of perjury or struck off at the time, and most had very distinguished careers. However, Arthur Newton was struck off for 12 months for professional misconduct in 1910 after falsifying letters from another of his clients—the notorious murderer Harvey Crippen.[65] In 1913, he was struck off indefinitely and sentenced to three years' imprisonment for obtaining money by false pretences.[66] Newton may have invented and spread the rumours about Prince Albert Victor in an attempt to protect his clients from prosecution by forcing a cover-up.[67]

State papers on the case in the Public Record Office, released to the public in the 1970s, provide no information on the prince's involvement other than Newton's threat to implicate him.[68] Hamilton Cuffe wrote to the Director of Public Prosecutions, Sir Augustus Stephenson, "I am told that Newton has boasted that if we go on a very distinguished person will be involved (PAV). I don't mean to say that I for one instant credit it—but in such circumstances as this one never knows what may be said, be concocted or be true."[69] Surviving private letters from Somerset to his friend Lord Esher, confirm that Somerset knew of the rumours but did not know if they were true. He writes, "I can quite understand the Prince of Wales being much annoyed at his son's name being coupled with the thing ... we were both accused of going to this place but not together ... I wonder if it is really a fact or only an invention."[70] In his correspondence, Sir Dighton Probyn refers to "cruel and unjust rumours with regard to PAV" and "false reports dragging PAV's name into the sad story".[71] When Prince Albert Victor's name appeared in the American press, the New York Herald published an anonymous letter, almost certainly written by Charles Hall, saying "there is not, and never was, the slightest excuse for mentioning the name of Prince Albert Victor."[72] Biographers who believe the rumours suppose that Prince Albert Victor was bisexual,[73] but that is strongly contested by others, who refer to him as "ardently heterosexual" and his involvement in the rumours as "somewhat unfair".[74]

In 1902, an American newspaper alleged that Lord Arthur Somerset, having learned in some way that 19 Cleveland Street was under police surveillance and that he may have been identified as a visitor, contrived to bring the prince to the house on an innocent pretext in the hope that the police, seeing him cross the threshold, would be afraid to take the case any further. The report alleged the ruse Somerset used was the prince's fondness for boulle furniture: he invited him to inspect a boulle cabinet which was in the house, and the prince remained there for no more than five minutes.[75]

The warrant for Somerset's arrest remained open, and he never returned to England. For more than thirty years he lived incognito in his self-imposed exile, until his death in 1926. He was buried in the town cemetery of Hyères, and his headstone gave his true name and paternity.[76]

House[edit]

The site of the brothel at 19 Cleveland Street, Marylebone, and its historical context within the homosexual and other transgressive communities of London's Fitzrovia and neighbouring Soho and Bloomsbury, has become the subject of academic study and general interest.[77][78][79] In Parliament, Labouchère indignantly described 19 Cleveland Street as "in no obscure thoroughfare, but nearly opposite the Middlesex Hospital".[80] The house, which was located on the western side of Cleveland Street, no longer survives: it was demolished in the 1890s for an extension of the hospital,[81][82] which itself was bulldozed in 2005.[83] Two sketches of the house were published by The Illustrated Police News.[84]

It has occasionally been claimed that the house survives. This theory proposes that, following a renumbering of the street, No. 19 was deleted from the Land Survey to suppress its existence, and that the house is the current No. 18 on the eastern side of the street.[85][86] Cleveland Street was indeed renumbered: the southernmost end was originally Norfolk Street. (For example, the current number 22 Cleveland Street, was originally 10 Norfolk Street, and for a time was the home of Charles Dickens.)[87] However, the renumbering of Cleveland Street was ordered in 1867, long before the scandal, by the Metropolitan Board of Works: "the odd numbers, commencing with 1 and ending with 175, being assigned to the houses on the Western side; that the even numbers, commencing with 2 and ending with 140, to those on the Eastern side; that such numbers do commence at the Southern end."[88] An Ordnance Survey of 1870 also shows No. 19 and its adjacent houses on the street's western side.[89] In an 1894 Ordnance Survey these properties have been subsumed by the new Middlesex Hospital wing.[90]

See also[edit]

Notes and sources[edit]

- ^ Aronson, p. 177.

- ^ Lees-Milne, James (1986). The Enigmatic Edwardian. Sidgwick and Jackson. p. 82.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 8–10, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 20–23.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 11, 16–17, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 23–24.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 23.

- ^ Aronson, p. 11, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 25.

- ^ Aronson, p. 135.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 26–33.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 11, 133, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 25.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 134–135, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 34–35.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 35.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 38.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 35, 45, 47.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 42, 46.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 47–53.

- ^ Aronson, p. 137

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 74–77.

- ^ Aronson, p. 136, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 27, 34.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 61.

- ^ Aronson, p. 140, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 82–86.

- ^ Aronson, p. 142.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 93.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 94.

- ^ Ridley, Jane (2013). The Heir Apparent. Random House. p. 657, n. 84.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 97.

- ^ Aronson, p. 144, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 98–99.

- ^ Aronson, p. 150.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 134-35 and 246.

- ^ "The London Scandals", The Press (New Zealand), Volume XLVI, Issue 7418, 9 December 1889, p. 6.

- ^ "The West End Scandal: Another Flight", Evening News (Sydney, Australia), Tuesday 14 January 1890.

- ^ "Another London Society Leader Gone", The Salt Lake Herald, Wednesday 1 January 1890.

- ^ "La Marquise de Fontenoy" (pseudonym of Marguerite Cunliffe-Owen), Chicago Tribune, 8 May 1916.

- ^ "Vanity Fair" by J.M.D., The Australasian (Melbourne), 22 September 1894.

- ^ "Boulanger Mixed Up in a Scandal", Chicago Tribune, 2 February 1890, p. 4.

- ^ "Brevities by Cable", Chicago Tribune, 1 August 1890.

- ^ "Notes on Current Topics", The Cardiff Times 7 December 1889, p. 5.

- ^ "The Cleveland Street Scandal", The Press (Canterbury, New Zealand), Volume XLVII, Issue 74518, 6 February 1890, p. 6.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 106–107.

- ^ North London Press, 16 November 1889, quoted in Hyde, The Other Love, p. 125.

- ^ Aronson, p. 150, and Hyde, The Other Love, p. 125.

- ^ Hyde, The Other Love, p. 123.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 151–159, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 113–116, 139–143.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 108.

- ^ Saul quoted in Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 146–147.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 151–159, and Hyde, The Other Love, pp. 125–127.

- ^ Hyde, The Other Love, p. 127.

- ^ Aronson, p. 160.

- ^ "Lord Euston's Libel Case", South Australian Register, 18 February 1890, p. 5.

- ^ "The Worst Judge I Ever Knew", The Argus (Melbourne), 15 May 1915.

- ^ Aronson, p. 153, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 135.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 162–207.

- ^ Aronson, p. 173.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 208–212.

- ^ a b Mr Labouchere's Suspension, Northampton Mercury 8 March 1890, p. 5.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, pp. 215–231.

- ^ In chapter 12 of the original 1890 version, one of the characters, Basil Hallward, refers to "Sir Henry Ashton, who had to leave England, with a tarnished name". See Bristow, Joseph (2006). "Explanatory Notes" In: Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oxford World's Classic, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280729-8. p. 221.

- ^ "Reviews and Magazines". Scots Observer, 5 July 1890, p. 181.

- ^ Bristow, Joseph (2006). "Introduction" In: Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Oxford World's Classic, Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-280729-8. p. xxi.

- ^ a b Ackroyd, Peter (1985). "Appendix 2: Introduction to the First Penguin Classics Edition" In: Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Penguin Classics, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-043784-3. pp. 224–225.

- ^ Mighall, Robert (2000). "Introduction" In: Wilde, Oscar. The Picture of Dorian Gray. Penguin Classics, Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-043784-3. p. xvi.

- ^ Kaplan, Morris B. (2004). "Literature in the Dock: The Trials of Oscar Wilde". Journal of Law and Society 31: (No. 1) 113–130.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 45.

- ^ Lees-Milne, p. 231.

- ^ Cook, pp. 284–285.

- ^ Cook, pp. 285–286, and Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 253.

- ^ Prince Eddy: The King We Never Had. Channel 4. Accessed 1 May 2010.

- ^ Cook, pp. 172–173.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 55.

- ^ Lord Arthur Somerset to Reginald Brett, 2nd Viscount Esher, 10 December 1889, quoted in Cook, p. 197.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 127.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 129.

- ^ Aronson, pp. 116–120, 170, 217.

- ^ Bradford, p. 10.

- ^ "Assails King's Dead Son", Chicago Tribune, 12 September 1902.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, p. 246-7.

- ^ Houlbrook, Matt (2006). Queer London: Perils and Pleasures in the Sexual Metropolis, 1918–1957, University of Chicago Press, p. 4.

- ^ Hallam, Paul (1993). The Book of Sodom, London: Verso, pp. 13–96.

- ^ Delgado, Anne (2007) "Scandals In Sodom: The Victorian City's Queer Streets" in Studies in the Literary Imagination, vol. 40, no. 1.

- ^ Cook, Matt (2003). London and the Culture of Homosexuality, 1885–1914. Cambridge University Press. p. 56.

- ^ Inwood, Stephen (2008). Historic London: An Explorer's Companion, Macmillan, p. 327.

- ^ Duncan, Andrew (2006). Andrew Duncan's Favourite London Walks, New Holland Publishers, p. 93.

- ^ Foot, Tom (25 September 2015) "Glowing reviews! Fitzrovia chapel reopens to the public after £2million restoration" Archived 16 February 2016 at the Wayback Machine, West End Extra.

- ^ Hyde, The Cleveland Street Scandal, between pp 208 and 209.

- ^ Gwyther, Matthew (21 October 2000) "Inside Story: 19 Cleveland Street", Daily Telegraph.

- ^ Glinert, Ed (2003). The London Compendium, Penguin Books.

- ^ "Plaque unveiled to identify Charles Dickens first London home", Fitzrovia News, 10 June 2013.

- ^ Minutes of Proceedings of the Metropolitan Board of Works, July–December 1867, p. 983

- ^ Ordnance Survey 1870: London (City of Westminster; St Marylebone; St Pancras), National Library of Scotland, View map

- ^ Ordnance Survey 1894: London, Sheet VII, National Library of Scotland, View map

References[edit]

- Aronson, Theo (1994). Prince Eddy and the Homosexual Underworld. London: John Murray. ISBN 0-7195-5278-8

- Bradford, Sarah (1989). King George VI. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-79667-4

- Cook, Andrew (2006). Prince Eddy: The King Britain Never Had. Stroud, Gloucestershire: Tempus Publishing Ltd. ISBN 0-7524-3410-1

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1970). The Other Love: An Historical and Contemporary Survey of Homosexuality in Britain. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0-434-35902-5

- Hyde, H. Montgomery (1976). The Cleveland Street Scandal. London: W. H. Allen. ISBN 0-491-01995-5

- Lees-Milne, James (1981). Harold Nicolson: A Biography. Volume 2: 1930–1968 London: Chatto & Windus. ISBN 0-7011-2602-7

Further reading[edit]

- Simpson, Colin; Chester, Lewis and Leitch, David (1976). The Cleveland Street Affair. Boston: Little, Brown.

- Zanghellini, Aleardo (2015). The Sexual Constitution of Political Authority: The 'Trials' of Same-Sex Desire. London: Routledge. ISBN 978 0-415-82740-9

- 1889 in London

- 19th century in LGBT history

- 19th-century scandals

- LGBT history in England

- Male prostitution

- Prostitution in England

- Fitzrovia

- History of gay men in the United Kingdom

- Political sex scandals in the United Kingdom

- LGBT-related political scandals

- Prince Albert Victor, Duke of Clarence and Avondale