German torpedo boat Seeadler

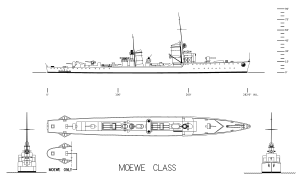

Right elevation and plan of the Type 23

| |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name | Seeadler |

| Namesake | Sea eagle |

| Builder | Reichsmarinewerft Wilhelmshaven |

| Yard number | 103 |

| Laid down | 5 October 1925 |

| Launched | 15 July 1926 |

| Commissioned | 15 March 1927 |

| Fate | Torpedoed and sunk, 14 May 1942 |

| General characteristics (as built) | |

| Class and type | Type 23 torpedo boat |

| Displacement | |

| Length | 87.7 m (287 ft 9 in) (o/a) |

| Beam | 8.25 m (27 ft 1 in) |

| Draft | 3.65 m (12 ft) |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | 2 × shafts; 2 × geared steam turbine sets |

| Speed | 32–34 knots (59–63 km/h; 37–39 mph) |

| Range | 1,800 nmi (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph) |

| Complement | 120 |

| Armament |

|

Seeadler was the second of six Type 23 torpedo boats built for the German Navy (initially called the Reichsmarine and then renamed as the Kriegsmarine in 1935). The boat made multiple non-intervention patrols during the Spanish Civil War in the late 1930s. During World War II, she played a minor role in the Battle of Kristiansand during the Norwegian Campaign of 1940. Seeadler spent the next couple of years escorting minelayers as they laid minefields and laying minefields herself. She also spent the latter half of 1941 escorting convoys through the Skaggerak. The boat returned to France in 1942 and was one of the escorts for the capital ships sailing from France to Germany through the English Channel in the Channel Dash. Seeadler then helped to escort one commerce raider through the Channel and was sunk by British forces while escorting another blockade runner in May.

Design and armament[edit]

Derived from the World War I-era large torpedo boat SMS H145,[Note 1] the Type 23 torpedo boat was slightly larger, but had a similar armament and speed.[1] The Type 23 had an overall length of 87.7 meters (287 ft 9 in) and was 85.7 meters (281 ft 2 in) long at the waterline.[2] The ships had a beam of 8.25 meters (27 ft 1 in), and a mean draft of 3.65 meters (12 ft). They displaced 923 long tons (938 t) at standard load and 1,290 long tons (1,310 t) at deep load.[3] Seeadler was fitted with a pair of Germania geared steam turbine sets, each driving one propeller, that were designed to produce 23,000 shaft horsepower (17,000 kW) using steam from three water-tube boilers which would propel the ship at 33 knots (61 km/h; 38 mph).[4] The torpedo boats carried enough fuel oil to give them an intended range of 3,600 nautical miles (6,700 km; 4,100 mi) at 17 knots (31 km/h; 20 mph),[1] but it proved to be only 1,800 nmi (3,300 km; 2,100 mi) at that speed in service. Their crew consisted of 4 officers and 116 sailors.[3]

As built, the Type 23s mounted three 10.5 cm (4.1 in) SK L/45[Note 2] guns, one forward and two aft of the superstructure; the aft superfiring gun was on an open mount while the others were protected by gun shields.[6] They carried six above-water 50 cm (19.7 in) torpedo tubes in two triple mounts[2] and could also carry up to 30 mines. After 1931, the torpedo tubes were replaced by 533-millimeter (21 in) tubes[1] and a pair of 2-centimeter (0.8 in) C/30[Note 3] anti-aircraft guns were added. During the war another pair of 2 cm guns may have been added before her loss.[8]

Construction and career[edit]

Named after the sea eagle, the boat was laid down at the Reichsmarinewerft Wilhelmshaven (Navy Yard) on 15 July 1926[4] as yard number 103,[9] launched on 15 March 1927 and commissioned on 15 May 1928.[4] By the end of 1936 Seeadler was assigned to the 2nd Torpedo Boat Flotilla and the boat made several deployments to Spain during the Spanish Civil War. The boat ran aground leaving Cadiz harbor in November 1936 and had to be escorted home for repairs by her sister ship Albatros. After the heavy cruiser Deutschland was hit by two bombs from Republican aircraft on 29 May 1937, Adolf Hitler ordered the heavy cruiser Admiral Scheer to bombard the Republican-held city of Almería in retaliation. On 31 May the ship did so, accompanied by the four boats of the 2nd Flotilla, targeting Republican coastal artillery, naval building and ships in the harbor, killing nineteen people.[10] Seeadler and Albatros participated in the bombardment and the former was near-missed by coast-defense guns.[11] Around June 1938, she was transferred to the newly formed 4th Torpedo Boat Flotilla.[12]

Second World War[edit]

At the beginning of the war, the 4th Flotilla was disbanded and Seeadler was transferred to the 6th Torpedo Boat Flotilla where she supported the North Sea mining operations that began on 3 September 1939. On 13, 18 and 19 November, the 6th Flotilla and one or two light cruisers met destroyers returning from minelaying missions off the English coast. Two days later the flotilla patrolled the Skagerrak to inspect neutral shipping for contraband goods before returning to port on the 25th. From 14 to 16 December, Seeadler and the torpedo boat Jaguar made contraband patrols in the Skaggerak, impounding six ships. In retaliation for the Altmark Incident where the Royal Navy seized captured British sailors from the German tanker Altmark in neutral Norwegian waters on 16 February, the Kriegsmarine organized Operation Nordmark to search for Allied merchant ships in the North Sea as far north as the Shetland Islands. The 2nd Destroyer Flotilla, Seeadler and the torpedo boat Luchs escorted the battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Admiral Hipper during the initial stages of the sortie on 18 February before patrolling the Skaggerak until the 20th.[13]

During the Invasion of Norway in April 1940, the boat was assigned to Group 4 under Kapitän zur See (Captain) Friedrich Rieve on the light cruiser Karlsruhe, tasked to capture Kristiansand. They departed Wesermünde on the morning of 8 April and arrived off Kristiansand the following morning, delayed by heavy fog. They had been spotted approaching the city and the alerted coast-defense guns at Odderøya Fortress opened fire on Karlsruhe at 05:32. The cruiser, Seeadler and Luchs returned fire. Neither side inflicted any damage on the other, although several of Karlsruhe's shells missed their targets and impacted in the city. With only his forward guns able to bear and his ships loaded with troops, Rieve ordered them to turn away and lay a smoke screen to cover their withdrawal at 05:45. Shortly afterwards, a flight of six Heinkel He 111 bombers from Kampfgeschwader 4 (Bomber Wing) attacked the fortress. Most of their bombs fell outside the fortifications, but one blew up the western ammunition dump and another near the signal station, killing two men and cutting most external communication lines. Encouraged by sight of the blast from the annumition dump and the numerous hits all over the island on which the fortress was built, Rieve ordered his ships to make another try at 05:55, this time at an angle so that all guns could bear. Accuracy for both sides was better this time, but no German ship was damaged and only a couple of shells from Karlsruhe landed inside the fort, wounding several gunners. With no discernable effect on the Norwegian defenses, Rieve was forced to withdraw again at 06:23. He now conceived the idea of bombarding the fortress at long range where he could use plunging fire to attack the guns from above and Karlsruhe would be out of range of the defending guns. The ship opened fire at 06:50 and Rieve ordered Seeadler and Luchs to steam through the narrows, but the fog closed in before they could get there and he had to cancel his order. The cruiser's fire was generally ineffective, with more shells landing in the city, so Rieve withdrew around 07:30 and requested additional air support.[14]

Around that time a British reconnaissance aircraft overflew Kristiansand, but failed to see the German ships off shore. The naval commander of the area queried the supreme command whether British forces should be engaged or not and received the order to let them pass. He passed that order to Odderøya at 08:05. Rieve made another attempt to force the narrows around 09:00 when the fog briefly lifted, but nearly ran Karlsruhe aground and withdrew again. Getting desperate, Rieve ordered his troops loaded onto four of his small E-boats when the fog began to lift again at 09:25 and ordered them to storm the harbor regardless of casualties. An hour later, the Norwegians spotted the incoming German ships with Seeadler and Luchs approaching at high speed, followed by the four E-boats. They were reported at two cruisers and their approach from a different direction caused some observers to think that they were not German, especially since there had been a rumor earlier of British ships spotted in the Skaggerak. The confusion was compounded when observers reported that they were flying the French tricolor flag, confusing it with a Kriegsmarine signal flag of similar color. This caused the Norwegians to think that they were being saved by Allied ships and their guns did not open fire so the Germans landed without resistance and occupied the defenses beginning around 10:45.[15]

Rieve was under orders to return to Kiel as soon as possible, so Karlsruhe sailed at 18:00, escorted by Seeadler, her sister Greif, and Luchs. At 18:58, one torpedo from the British submarine Truant struck the cruiser amidships, knocking out all power, steering and the pumps. Luchs evaded the other nine torpedoes and followed them to their origin and began depth charging the submarine for the next several hours, joined by the other two torpedo boats. Truant was damaged, but survived their attacks. Rieve ordered his crew aboard the torpedo boats and sent Seeadler and Luchs ahead while he remained with Greif to finish off Karlsruhe with a pair of torpedoes. After the heavy cruiser Lützow had been crippled by a British submarine off the Danish coast on 11 April, Seeadler, Greif and Luchs, among other ships, arrived the following morning to render assistance.[16]

On 18 April, Seeadler and her sisters Möwe, Greif, and the torpedo boat Wolf escorted minelayers as they laid anti-submarine minefields in the Kattegat. The boat began a refit at Wesermünde that lasted from May to August after which she was transferred to France. Now assigned to the 5th Flotilla, Seeadler and her sisters, Greif, Falke, and Kondor laid a minefield in the English Channel on 30 September – 1 October. Reinforced by Wolf and Jaguar, the flotilla made an unsuccessful sortie off the Isle of Wight on 8–9 October. They made a second, more successful, sortie on 11–12 October, sinking two Free French submarine chasers and two British trawlers. The 5th Flotilla was transferred to St. Nazaire later that month and its ships laid a minefield off Dover on 3–4 December and another one in the Channel on 21–22 December.[17]

Seeadler, the torpedo boat Iltis and the destroyer Z4 Richard Beitzen were the escorts for a minelaying mission at the northern entrance to the Channel on 23–24 January 1941. The boat was refitted in Rotterdam, Netherlands, from March to May 1941. She was transferred afterwards to the Skagerrak where she was on convoy escort duties. The boat was again refitted in Rotterdam from December 1941 to February 1942 before rejoining the 5th Flotilla. They joined the escort force for Scharnhorst, Gneisenau and the heavy cruiser Prinz Eugen on 12 February 1942 off Cap Gris-Nez during the Channel Dash. From 12 March to 2 April, the flotilla escorted the commerce raider Michel through the Channel despite heavy British attacks, damaging the British destroyers HMS Walpole and Fernie. The flotilla escorted the commerce raider Stier through the English Channel from 12 to 19 May. In heavy fighting on the 13th, British motor torpedo boats torpedoed Seeadler, which capsized and then broke in half with the loss of 85 crewmen.[18]

Notes[edit]

- ^ "SMS" stands for "Seiner Majestät Schiff" (German: His Majesty's Ship).

- ^ In Imperial German Navy gun nomenclature, "SK" (Schnelladekanone) denotes that the gun is quick firing, while the L/45 denotes the length of the gun. In this case, the L/45 gun is 45 caliber, meaning that the gun is 45 times as long as it is in diameter.[5]

- ^ In Kriegsmarine gun nomenclature, SK stands for Schiffskanone (ship's gun), C/30 stands for Constructionjahr (construction year) 1930.[7]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Gröner, p. 191

- ^ a b Sieche, p. 237

- ^ a b Whitley 1991, p. 202

- ^ a b c Whitley 2000, p. 57

- ^ Friedman, pp. 130–131

- ^ Whitley 1991, p. 45

- ^ Campbell, p. 219

- ^ Whitley 1991, pp. 47, 202; Whitley 2000, p. 57

- ^ Gröner, p. 192

- ^ Haar 2013, pp. 32–33

- ^ Whitley 1991, p. 79

- ^ Whitley 1991, pp. 77–79

- ^ Rohwer, pp. 2, 8–11, 15

- ^ Haar 2009, pp. 81, 201–206

- ^ Haar 2009, pp. 207–214

- ^ Haar 2009, pp. 377–379, 382

- ^ Rohwer, pp. 20, 43, 45, 51–52; Whitley 1991, pp. 109, 208

- ^ Gröner, p. 193; Rohwer, pp. 57, 143, 151, 165; Whitley 1991, pp. 120–121, 208

Bibliography[edit]

- Campbell, John (1985). Naval Weapons of World War II. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-0-87021-459-2.

- Friedman, Norman (2011). Naval Weapons of World War One: Guns, Torpedoes, Mines and ASW Weapons of All Nations; An Illustrated Directory. Barnsley, UK: Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84832-100-7.

- Gröner, Erich (1990). German Warships 1815–1945. Vol. 1: Major Surface Warships. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 0-87021-790-9.

- Haarr, Geirr H. (2013). The Gathering Storm: The Naval War in Northern Europe September 1939 – April 1940. Annapolis: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-331-4.

- Haarr, Geirr H. (2009). The German Invasion of Norway, April 1940. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 978-1-59114-310-9.

- Rohwer, Jürgen (2005). Chronology of the War at Sea 1939–1945: The Naval History of World War Two (Third Revised ed.). Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-59114-119-2.

- Sieche, Erwin (1980). "Germany". In Chesneau, Roger (ed.). Conway's All the World's Fighting Ships 1922–1946. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-146-7.

- Whitley, M. J. (2000). Destroyers of World War Two: An International Encyclopedia. London: Cassell & Co. ISBN 1-85409-521-8.

- Whitley, M. J. (1991). German Destroyers of World War Two. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1-55750-302-8.