A Voyage Round the World

Title page from the first edition of A Voyage Round the World | |

| Author | Georg Forster |

|---|---|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Travel literature |

| Publisher | Benjamin White |

Publication date | 17 March 1777 |

| Publication place | England |

| Pages | 1200 (in two volumes) |

| OCLC | 311900474 |

A Voyage Round the World (complete title A Voyage Round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5) is Georg Forster's[nb 1] report on the second voyage of the British explorer James Cook. During the preparations for Cook's voyage, the expedition's naturalist Joseph Banks had withdrawn his participation, and Georg's father, Johann Reinhold Forster, had taken his place at very short notice, with his seventeen-year-old son as his assistant. They sailed on HMS Resolution with Cook, accompanied by HMS Adventure under Tobias Furneaux. On the voyage, they circumnavigated the world, crossed the Antarctic Circle and sailed as far south as 71° 10′, discovered several Pacific islands, encountered diverse cultures and described many species of plants and animals.

When they returned to England after more than three years, disagreement about the publication rights for a narrative of the journey arose. After plans agreed with John Montagu, 4th Earl of Sandwich, the First Lord of the Admiralty, to publish a joint work with contributions by both Cook and Reinhold Forster had fallen through, Georg, who was not bound by any agreement with the Admiralty, began writing Voyage in July 1776. He published on 17 March 1777, six weeks before Cook's A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World appeared. While 63 copper engravings, paid for by the Admiralty, illustrated Cook's account, only a chart of the Southern Hemisphere showing the expedition ships' courses illustrated Forster's Voyage, which was sold for the same price.

While Forster organised Voyage chronologically, he wrote it as entertaining literature, focusing not on the nautical aspects of the voyage but on scientific observations and on the cultural encounters with the peoples of the South Pacific. This was well received by critics, who praised the writing, especially in contrast to Cook's book, but sales were slow. Controversy continued after the publication. Resolution astronomer William Wales suspected Reinhold Forster of being the true author and published many accusations in his Remarks on Mr Forster's Account of Captain Cook's last Voyage round the World that prompted a Reply to Mr Wales's Remarks in which Georg defended his father against the attacks. Voyage brought Georg Forster great fame, especially in Germany. It is regarded as a seminal book in travel writing, considered a major influence on the explorer Alexander von Humboldt, and has become a classic of travel literature.

Background

[edit]

The Royal Society of London suggested James Cook's first voyage, 1768–1771, to observe the 1769 transit of Venus from Tahiti.[8][9] Following proposals by the geographer Alexander Dalrymple, the scope was widened to a voyage of discovery that was hoped to find the hypothetical continent of Terra Australis Incognita.[10] Cook circumnavigated New Zealand, proving it was not attached to a landmass farther south, and mapped the east coast of Australia but had not found evidence for a large southern continent. After Cook's return, a second voyage was commissioned with the aim of circumnavigating the globe as far south as possible to finally find this famed continent.[11][12] In the preparations for Cook's second voyage, Joseph Banks, the botanist on the first voyage, had been designated as the main scientific member of the crew. He asked for major changes to the expedition ship, HMS Resolution, which made it top-heavy and had to be mostly undone. Subsequently, dissatisfied with the ship, Banks announced on 24 May 1772 his refusal to go on the expedition.[13][14]

On 26 May 1772,[15] Johann Reinhold Forster, who had attempted unsuccessfully to become part of Banks's scientific entourage,[16] was visited by the naval surgeon and inventor Charles Irving, who told Forster of Banks's decision and asked whether he would go instead.[15][17] Forster accepted but requested that his seventeen-year-old son Georg should accompany him as his assistant.[18][19] Irving relayed this to the First Secretary of the Admiralty, Philip Stephens. Forster was supported by the Royal Society's vice president Daines Barrington, whose friendship he had cultivated.[20] The First Lord of the Admiralty, Lord Sandwich obtained the king's assent for Forster's appointment on 5 June, pre-empting attempts by Banks to force the Admiralty to comply with his demands.[21][22] Financial questions still needed to be resolved. Barrington attempted to secure for Forster the £4,000 that Parliament had approved for Banks's would-be companion, James Lind. After Lord Sandwich recommended Forster to the prime minister, Lord North, as "one of the fittest persons in Europe for such an undertaking", mentioning Georg as a "very able draughtsman and designer",[23] Lord North obtained the King's approval for a payment of £1,795 for equipment that Forster received on 17 June, as the first instalment of the £4,000.[24][25] Additionally, despite not having a written contract and relying on Barrington's word only, Reinhold Forster believed he would be allowed to publish a narrative of the journey.[26]

The second voyage of James Cook began with Resolution and Adventure sailing from Plymouth on 13 July 1772.[27] Other than sailing to the Cape of Good Hope and back, the journey can be broken up into three "ice edge cruises" during the Southern hemisphere summers, where Cook attempted to find Terra Australis, broken up by "tropical sweeps" in the South Pacific and stays at a base in New Zealand.[28] While they did not reach mainland Antarctica, they made the first recorded crossing of the Antarctic Circle on 17 January 1773.[29] They discovered New Caledonia, South Georgia and the South Sandwich Islands. Finally, Cook's ship returned to England on 30 July 1775.[30] An abstract of one of Forster's letters to Barrington summarised the achievements for Banks as "260 new Plants, 200 new Animals – 71° 10′ farthest Sth – no continent – Many Islands, some 80 Leagues long – The Bola Bola savage an [in]corrigible Blockhead – Glorious Voyage – No man lost by sickness."[31][nb 2]

Publication rights dispute

[edit]After the return of Cook's expedition, there was disagreement about who should write the official account of the journey. After Cook's first voyage in 1768, the writer and editor John Hawkesworth had compiled a report, An Account of the Voyages, from the journals of Cook and Banks. He had been recommended to Lord Sandwich by their mutual friend Charles Burney and received compensation of £6,000.[34] Hawkesworth's report was poorly received by critics.[35] Cook was also dissatisfied with gross inaccuracies in the report,[36] which according to Hawkesworth had been approved by him.[37] After this experience, Cook decided to publish his own account.[38] Reinhold Forster believed he would be allowed to write the official report of the voyage and reap the expected financial rewards from it. Both Cook and Forster had kept journals for this purpose and reworked them in the winter of 1775–76. In April 1776, Sandwich brokered a compromise that both sides agreed to: Cook would write the first volume, containing a narrative of the journey, the nautical observations, and his own remarks on the natives. The elder Forster was to write the second volume concerning the discoveries made in natural history and ethnology and his "philosophical remarks". Costs and profits were to be shared equally, but the Admiralty was to pay for the engravings.[39][40] However, when Forster had completed a sample chapter, Sandwich was dissatisfied with it and asked Richard Owen Cambridge to revise the manuscript.[41] Forster, who mistakenly assumed that Barrington wanted to correct his work,[42] was furious about this interference with his writing and refused to submit his drafts for corrections. He offered to sell his manuscripts to the Admiralty for £200,[43] which Cook and Barrington supported, but Sandwich refused.[44] In June 1776, it was decided that Cook would publish his report alone,[45][46] giving Cook the full financial benefit of the publication.[47] Reinhold Forster's agreements with Sandwich made it impossible for him to publish a separate narrative.[48]

Writing and publication

[edit]

Not bound by his father's agreements with the Admiralty, Georg Forster began to write A Voyage Round the World in July 1776, which fully engaged him for nine months.[48][49][50] His father's journals were the main source for the work.[43] The facts about what they saw and did are typically taken from these journals but recast into Georg's own style, with a different ordering of the details and additional connecting material.[51] Some parts were based on segments of Cook's journals that Forster's father had accessed while preparing his samples for Sandwich.[52][53] Georg used his own notes and recollections,[54] including his own memorandum Observationes historiam naturalem spectantes quas in navigationes ad terras australes institutere coepit G. F. mense Julio, anno MDCCLXXII, which contains botanical and biological observations up to 1 January 1773.[55][nb 3]

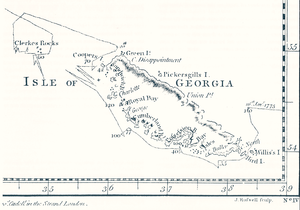

Unlike the systematic approach of Johann Reinhold Forster's later book Observations Made during a Voyage round the World (1778), A Voyage Round the World is a chronology of the voyage,[57] but written as entertaining literature, including the use of quotations from classical literature to frame the narrative,[58] instead of a dry collection of facts.[59] Among the first books using such scientific-literary techniques, it is regarded as a seminal book in the history of travel writing[60] and has been described as "unambiguously the finest of the Cook voyage narratives".[61] The Oxford astronomer Thomas Hornsby proofread the book's manuscript.[62][63][64] Georg Forster drew a chart for the book, which was engraved by William Whitchurch. It shows most of the Southern Hemisphere in stereographic projection from the intersection of the Arctic Circle and the meridian of Greenwich. The chart shows the tracks of the expedition's ships more clearly than the one printed in Cook's account, which included those of other navigators.[65] Reinhold Forster attempted to access the plates with the engravings that were made for Cook's account, but was refused by the publishers. Nevertheless, Georg had seen proofs of these plates, frequently mentioned and commented on in Voyage.[50]

The book appeared on 17 March 1777,[66] printed in two volumes totalling 1200 pages by the publisher Benjamin White. Cook's official account of the voyage, A Voyage Towards the South Pole and Round the World, appeared six weeks later. Cook's book included 63 copper engravings,[67] some of which were based on Georg Forster's drawings, while A Voyage Round the World was not illustrated except for the chart. Nevertheless, both books were sold at the same price of 2 guineas.[68] Forster's book sold slowly; in 1778, 570 of about 1000 copies were still unsold,[67] and the Forsters had to sell most of their collection of Pacific artefacts and Georg's drawings to alleviate their debts. Some of the drawings were not published until 2007, when they appeared in an illustrated German edition of Voyage.[69]

Content

[edit]

The book is structured as a travelogue, chronologically retelling the events and observations of the journey. Unlike Cook's report, it does not focus on the nautical aspects of the voyage, but on the scientific and ethnological observations. Forster describes encounters with the peoples and cultures of the South Seas and the corrupting impact of the contact with European sailors.[70] Peoples described include the Tahitians, the Maori of New Zealand, and the Fuegians of Tierra del Fuego, whose technologies and societies Forster analysed and compared.[71]

The following is a summary of the contents of each chapter, following the journey of the Resolution under Cook, which was accompanied for parts of the journey by the Adventure under the command of Tobias Furneaux.

Preface

[edit]The greatest navigator of his time, two able astronomers, a man of science to study nature in all her recesses, and a painter to copy some of her most curious productions, were selected at the expence of the nation. After completing their voyage, they have prepared to give an account of their respective discoveries, which cannot fail of crowning, their employers at least, with immortal honour.[72]

Forster explains the history of the work, including the agreements between his father, Cook and Sandwich. He proceeds with an apology for producing a work separate to Cook's, and gives an account of the life in England of Tahitian native Omai, who had arrived in Europe on Adventure in 1774.

Book I

[edit]

Chapter I. Departure—Passage from Plymouth to Madeira—Description of that Island.

[edit]The Forsters travel from London to Plymouth. After final works on the Resolution have been completed, the sea voyage begins. They sail along the coast of Spain, then spend some days in Madeira. Forster describes the island on several pages.

Chapter II. The Passage from Madeira to the Cape Verd Islands, and from thence to the Cape of Good Hope.

[edit]The voyage passes the Canary Islands, then crosses the Tropic of Cancer. They visit Cape Verde. Forster comments on its inhabitants and their wretchedness, which he blames on "despotic governors, bigotted priests, and indolence on the part of the court of Lisbon".[73] On the way south, they encounter dolphins, flying fish, and some luminous sea creatures.

Chapter III. Stay at the Cape of Good Hope.—Account of that Settlement.

[edit]The voyagers spend three weeks in Cape Town. Forster describes the colony, which he finds far superior to the Portuguese colony at Cape Verde. They meet Anders Sparrman, a Swedish naturalist, who agrees to accompany them.

Chapter IV. Run from the Cape to the Antarctic Circle; first season spent in high Southern Latitudes.—Arrival on the Coast of New Zeeland.

[edit]

The voyagers sail south, into unknown waters. As the weather gets colder, Cook provides the seamen with warm clothing. At 51° 5′ South, they encounter icebergs. William Wales and Forster's father get lost in the fog in a small boat, but eventually manage to return to the ship. The sailors are drunk at Christmas. Ice is brought on board to be melted. On 17 January 1773, they cross the Antarctic Circle:

On the 17th, in the forenoon, we crossed the antarctic circle, and advanced into the southern frigid zone, which had hitherto remained impenetrable to all navigators. ... About five o'clock in the afternoon, we had sight of more than thirty large islands of ice a-head; and perceived a strong white reflexion from the sky over the horizon. Soon after we passed through vast quantities of broken ice, which looked honey-combed and spungy, and of a dirty colour. This continually thickened about us, so that the sea became very smooth, though the wind was fresh as before. An immense field of solid ice extended beyond it to the south, as far as the eye could reach from the mast-head. Seeing it was impossible to advance farther that way, Captain Cook ordered the ships to put about, and stood north-east by north, after having reached 67° 15′ south latitude, where many whales, snowy, grey, and antarctic petrels, appeared in every quarter.[74]

The voyage continues eastwards, with occasional attempts to go further south. They lose contact with the Adventure. Several sailors suffer from symptoms of scurvy. They arrive in New Zealand at the end of February, "after a space of four months and two days, out of sight of land".[75]

Chapter V. Stay at Dusky Bay; description of it, and account of our transactions there.

[edit]

Resolution arrives at Dusky Bay, where they meet some natives and make several excursions. There are plenty of fish and many ducks to shoot. They leave some geese to breed and restock with water and timber. They stay for some days at Long Island. After six weeks in the area, Forster concludes:

The climate of Dusky Bay, is I must own, its greatest inconvenience, and can never be supposed a healthy one. During the whole of our stay, we had only one week of continued fair weather, all the rest of the time the rain predominated. But perhaps the climate was less noxious to Englishmen than to any other nation, because it is analogous to their own.[76]

Chapter VI. Passage from Dusky Bay to Queen Charlotte's Sound—Junction with the Adventure.—Transactions during our stay there.

[edit]The voyagers encounter a waterspout. At Queen Charlotte Sound, they are rejoined by the Adventure, and Forster reports on its journey to New Zealand via Tasmania. Again, they make several excursions, including one to another Long Island, where Cook has some seeds planted. Forster comments on the geology and concludes the existence of volcanoes in New Zealand. They trade with natives and invite them on board the ship, and the unmarried women are forced into prostitution by the natives:

Our crews, who had not conversed with women since our departure from the Cape, found these ladies very agreeable; ... However their favours did not depend upon their own inclination, but the men, as absolute masters, were always to be consulted upon the occasion; if a spike-nail, or a shirt, or a similar present had been given for their connivance, the lady was at liberty to make her lover happy, and to exact, if possible, the tribute of another present for herself. Some among them, however, submitted with reluctance to this vile prostitution; and, but for the authority and menaces of the men, would not have complied with the desires of a set of people who could, with unconcern, behold their tears and hear their complaints. ... Encouraged by the lucrative nature of this infamous commerce, the New Zeelanders went through the whole vessel, offering their daughters and sisters promiscuously to every person's embraces, in exchange for our iron tools, which they knew could not be purchased at an easier rate.[77]

Forster comments on the moral corruption inflicted upon the natives by the Europeans. The voyagers spend several more days in the areas and converse with the natives, and Cook shows one of them the seed garden on Long Island.

Chapter VII. Run from New Zeeland to O-Taheitee.

[edit]The ships pass through Cook's Strait and turn to the northeast. Forster reports on consumption of dog meat and on the relatively better health of the crew on board the Resolution as compared to the Adventure.

Chapter VIII. Anchorage in O-Aitepeha harbour, on the lesser peninsula of O-Taheitee.—Account of our stay there.—Removal to Matavai Bay.

[edit]

Forster describes the arrival in Tahiti:

It was one of those beautiful mornings which the poets of all nations have attempted to describe, when we saw the isle of O-Taheite, within two miles before us. The east-wind which had carried us so far, was entirely vanished, and a faint breeze only wafted a delicious perfume from the land, and curled the surface of the sea. The mountains, clothed with forests, rose majestic in various spiry forms, on which we already perceived the light of the rising sun: nearer to the eye a lower range of hills, easier of ascent, appeared, wooded like the former, and coloured with several pleasing hues of green, soberly mixed with autumnal browns. At their foot lay the plain, crowned with its fertile bread-fruit trees, over which rose innumerable palms, the princes of the grove. Here every thing seemed as yet asleep, the morning scarce dawned, and a peaceful shade still rested on the landscape.[78]

The natives are friendly, and come to the ship unarmed and in large numbers. Forster finds the language very easy to pronounce, and notices that the letter "O" that many words seem to begin with is just an article.

In the afternoon the captains, accompanied by several gentlemen, went ashore the first time, in order to visit O-Aheatua, whom all the natives thereabouts acknowledged as aree, or king. Numbers of canoes in the mean while surrounded us, carrying on a brisk trade with vegetables, but chiefly with great quantities of the cloth made in the island. The decks were likewise crouded with natives, among whom were several women who yielded without difficulty to the ardent sollicitations of our sailors. Some of the females who came on board for this purpose, seemed not to be above nine or ten years old, and had not the least marks of puberty. So early an acquaintance with the world seems to argue an uncommon degree of voluptuousness, and cannot fail of affecting the nation in general. The effect, which was immediately obvious to me, was the low stature of the common class of people, to which all these prostitutes belonged.[79]

They continue to trade, and an incident of theft is resolved after Cook confiscates a canoe. The Forsters go ashore to collect plants, and the natives help them, but do not sell their hogs, stating these belong to the king. They continue to enjoy the natives' hospitality and meet a very fat man who appears to be a leader. Some days later, Cook and his crew are granted an audience with the local chief, attended by 500 natives. Forster reports on the recent political history. They continue to Matavai Bay, where Cook had stayed during his previous visit to Tahiti.

Chapter IX. Account of our Transactions at Matavaï Bay.

[edit]

The voyagers meet the local king O-Too. An exchange of presents ensues, including several live animals. On excursions, the Forsters encounter more hospitality, including a type of refreshing massage. After two weeks, they leave Tahiti, and Forster remarks on the society of Tahiti, which he perceives as more equal than that of England, while still having class distinctions.

Chapter X. Account of our Transactions at the Society Islands.

[edit]Forster reports that some seamen have caught venereal diseases from their sexual encounters in Tahiti. They arrive at Huahine, and there is a welcoming ceremony for Cook. On an excursion, Forster and Sparrman notice a woman breastfeeding a puppy; upon inquiry, they find out she lost her child. The interactions with local chief Oree are described. Soon after, on Bora Bora, they shoot some kingfishers, which makes the women unhappy, and the local chief asks them not to kill kingfishers or herons, while allowing them to shoot other species. They discuss the nearby islands with the natives. Forster describes a dance performance. They visit O-Tahà, and Forster describes a feast, the local alcoholic beverages, and another dance performance.

Book II

[edit]Chapter I. Run from the Society Isles to the Friendly Isles, with an Account of our Transactions there.

[edit]Fully restocked, and with a crew that is healthy except for venereal diseases, the voyagers continue eastwards. Cook discovers Hervey's Isle. They meet the natives at Middelburg Island. Forster criticises related images by Hodges and Sherwin. The natives sing a song for them, a transcription of which is given in the book. Forster comments on the inhabitants' houses and their diet, and describes their tattoos and ear piercings. As there is little opportunity to trade, they continue to Tongatapu. Here again, the natives are friendly, and Forster sees one of their priests. During daytime, many women prostitute themselves on board the ship, all of them unmarried. Forster describes the natives' boats and their habit of colouring their hair with powders. The priest is seen drinking a kava-based intoxicating beverage and shares some with the travellers. Forster compares the Tahitians and the Tongans.

Chapter II. Course from the Friendly Isles to New Zeeland.—Separation from the Adventure.—Second stay in Queen Charlotte's Sound.

[edit]The ships sail back to New Zealand, where some natives in Hawke's Bay perform a war dance for them. A storm hinders them from passing west through Cook's Strait, and they have a terrible night, in which most of the beds are under water and the Forsters hear the curses of the sailors "and not a single reflection bridled their blasphemous tongues".[81] They lose sight of the Adventure, but finally manage to pass through Cook's Strait and return to Queen Charlotte's Sound on South Island. Forster describes various trades and excursions, and comments on the treatment of women:

Among all savage nations the weaker sex is ill-treated, and the law of the strongest is put in force. Their women are mere drudges, who prepare raiment and provide dwellings, who cook and frequently collect their food, and are requited by blows and all kinds of severity. At New Zeeland it seems they carry this tyranny to excess, and the males are taught from their earliest age, to hold their mothers in contempt, contrary to all our principles of morality.[82]

A shipmate buys the head of a victim of a recent fight, and takes it on board, where other natives proceed to eat the cheeks, proving the existence of cannibalism in New Zealand. Forster describes the mixed reactions of the company on board; the most shocked is Mahine, a native of Bora Bora, who accompanies them. They take provisions to continue their journey, with the "hope of completing the circle round the South-Pole in a high latitude during the next inhospitable summer, and of returning to England within the space of eight months".[83]

Chapter III. The second course towards the high southern latitudes from New Zeeland to Easter Island.

[edit]

Resolution sails south. Forster describes Mahine's reaction to seeing snow for the first time and to life on board. They observe Christmas at the Antarctic Circle, with icebergs often hindering their progress south. Going east and north again, they have finally "proved that no large land or continent exists in the South Sea within the temperate zone, and that if it exists at all, we have at least confined it within the antarctic circle".[84] Forster comments on the hardship of the voyage. When they turn south again, they are stopped at 71° 10′ south by "a solid ice-field of immense extent".[85] They turn north again towards the tropics; many crew are afflicted with scurvy, and the captain with other illnesses. They sail to Easter Island.

Chapter IV. An Account of Easter Island, and our Stay there.

[edit]As the voyagers come to Easter Island, the natives provide them with fresh bananas, which are very welcome to the crew that has lacked fresh provisions. Trade with the natives is not very successful, as they do not have much, and sometimes attempt to cheat. The sailors buy sexual favours fairly cheaply. Forster quotes from his father's journal, which describes seeing the moai (statues) and meeting the king. Forster closes with the observation by their companion Mahine, "the people were good, but the island very bad".[86]

Chapter V. Run from Easter Island to the Marquesas—Stay in Madre-de-Dios harbour on Waitahoo—Course from thence through the Islands to Taheitee.

[edit]As they sail slowly northwest towards the Marquesas Islands, many of the crew are sick again, including the captain. Forster's father has his dog killed to provide better food for Cook. When they arrive at the Marquesas, they trade with the natives for food. A native who has attempted to steal is shot dead by one of the officers. Forster describes the inhabitants and finds them overall very similar to those of the Society Islands. They sail to the King George Islands, discover the Palliser Islands, and return to Tahiti.

Chapter VI. An account of our second visit to the island of o-Taheitee.

[edit]

Forster describes a war fleet of canoes and some of the background of the war. Red feathers are highly valued by the natives, leading to offers of prostitution from higher-ranked women than before. Mahine marries a Tahitian girl, and the ceremony is witnessed by a midshipman, who can not relate any details; Forster laments the lost opportunity to observe the local customs. Forster describes the recent political and military history of the island. He concludes with a comparison of life in England and in Tahiti.

Chapter VII. The second stay at the Society Islands.

[edit]On their way from Tahiti to Huahine, they have a stowaway on board. Arrived at the island, they trade again, and there are various incidents involving theft. They encounter the arioi, a venerated religious order of people who remain childless by killing their newborn. It turns out that Mahine is a member of this order, but he is persuaded not to kill any of his own children. Forster describes more encounters and more of the religion and calendar of the natives.

Chapter VIII. Run from the Society to the Friendly Islands.

[edit]As they leave the Society Islands, about half of the crew suffer from venereal diseases. Forster discusses their prevalence and states that there is now proof that they existed before contact with Europeans. They discover Palmerston Island but do not go ashore. They continue to Savage Island, where they are attacked and retreat. They continue to Nomuka and other of the Friendly Islands, where people are similar to those of Tongatapu, and Forster describes their houses and their trade. The sailors celebrate the second anniversary of their departure by drinking.

Book III

[edit]

Chapter I. An account of our stay at Mallicollo, and discovery of the New Hebrides.

[edit]The voyagers sail in the vicinities of Aurora Island, Lepers Island and Whitsun Island. After seeing the volcano on Ambrym, they turn to Mallicollo, where they engage with the natives. Forster reports their language as different from all South Sea dialects they have encountered, especially in its use of consonants. The natives are described as intelligent and perceptive, and an account is given of their body modifications and clothing, their food and their drums. As the voyagers sail south, some of the officers suffer from poisoning after eating a red fish. They discover the Shepherd Islands and then Sandwich Island, and continue south to Erromango. There they attempt to land to obtain fresh water but are attacked by the natives. They see the light from a volcano at night and then anchor close to it at Tanna Island.

Chapter II. Account of our stay at Tanna, and departure from the New Hebrides.

[edit]

At Tanna, they meet the natives. As a demonstration of might, Cook has a cannon fired. When a man tries to steal the buoy, they fire more shots, without harming the natives. They manage to land and, after giving some presents to the natives and receiving coconuts in return, ask to take some fresh water and wood, which is granted. The next day, the natives come aboard to trade. When a man tries to take what he was bartering for without payment, Cook again uses firearms to punish the theft. Many natives gather on the shore in two groups, but Cook scares them away:

One of them, standing close to the water's edge, was so bold as to turn his posteriors towards us, and slap them with his hand, which is the usual challenge with all the nations of the South Sea. Captain Cook ordered another musket to be shot into the air, and, at this signal, the ship played her whole artillery, consisting of five four-pounders, two swivels, and four musketoons. The balls whistled over our heads, and making some havock among the coco-palms, had the desired effect, and entirely cleared the beach in a few moments.[87]

They stake out an area that the natives should not enter and have no more trouble with them. Forster describes their hairstyle, bodypaint, and scars as well as their weaponry. Forster and his father make several excursions on the island and learn the names of several nearby islands from the natives. Whenever they approach a certain area, they are stopped by the natives who threaten to eat them. They do not succeed in approaching the volcano but measure temperatures at solfataras (shallow craters) and hot springs. A native is shot dead by a marine despite Cook's orders. After 16 days, they depart. Forster comments at length on the island's geography, plants, animals and people. They sail near islands called Irronan and Anattom. Cook names the island group the New Hebrides. They sail north to Espiritu Santo and discover additional small islands off its eastern coast. Again, at Espiritu Santo, the language is different from those previously encountered.

Chapter III. Discovery of New Caledonia.—Account of our stay there.—Range along the coast to our departure.—Discovery of Norfolk Island.—Return to New Zeeland.

[edit]Sailing south, they discover New Caledonia, come in contact with the natives and go ashore. Forster describes the clothes, earrings, and tattoos of the natives. With their help, they find a watering place. William Wales and Cook observe a solar eclipse. Forster observes some native women cooking, but they send him away. Cook's clerk purchases a fish that the Forsters identify as a Tetraodon and warn against the possibility that it might be poisonous, but as Cook claims to have eaten the same fish before, a meal is made of its liver. The liver is so oily that Cook and the Forsters eat very little of it but still suffer symptoms of poisoning. When natives come aboard and see the fish, they make signs it is bad and suggest throwing it in the sea. The poisoning makes excursions difficult, and Forster apologises for the lack of interesting content, asking the reader "to consider our unhappy situation at that time, when all our corporeal and intellectual faculties were impaired by this virulent poison".[88] They meet an albino native. When the natives observe the travellers eating a large beef bone, they are surprised and assume that this is a sign of cannibalism, as they have never seen large quadrupeds. They depart, and Forster compares the people of New Caledonia with others they have encountered. They continue eastwards along the coast of New Caledonia, aiming for New Zealand, discovering further small islands and catching a dolphin. Sailing south, they discover Norfolk Island. They quickly sail onwards to arrive at Queen Charlotte Sound in New Zealand.

Chapter IV. Third and last stay at Queen Charlotte's Sound, in New Zeeland.

[edit]Resolution stays in Queen Charlotte's Sound for repairs and restocking. They learn that there has been a battle between natives and some Europeans, with many dead, and are concerned for the Adventure. Forster reports on what they found out later: a boat with 10 people had gone ashore to collect celery and scurvy-grass when natives stole one of their jackets. The Europeans fired at them until their ammunition was spent and were then killed by the natives. Forster reports on incidents of killings between New Zealanders and Europeans from other journeys. They make further excursions and interact and trade with the natives. Forster comments on their music, with some excerpts in musical notation. Having restocked with fish and antiscorbutics, they depart.

Chapter V. The course from New Zeeland to Tierra del Fuego.—Stay at Christmas Harbour.

[edit]They sail east towards Tierra del Fuego. They drop anchor in a small cove, 41 days after their departure from New Zealand. They make excursions and meet the natives, who Forster finds extraordinarily wretched. They sail on around Cape Horn, pass the eastern side of Tierra del Fuego and sail eastwards to the small islands near Staten Islands that Cook calls New Year's Islands.

Chapter VI. Stay at the New Year's Islands. Discovery of lands to the southward. Return to the Cape of Good Hope.

[edit]

Forster describes large seals called sea-lions. The crew hunt sea-lions and penguins. They sail to the east and discover Willis Islands and claim South Georgia for Great Britain. They sail around South Georgia, proving it is an island. They continue southward, but are stopped by ice fields, "greatly to the satisfaction of all the crew, who were at present thoroughly tired of this dreadful climate".[89] They sail east and discover Southern Thule and various other islands that Cook names Sandwich Land. Having exhausted their supply of antiscorbutic sauerkraut, they sail on to the Cape of Good Hope.

Chapter VII. Second stay at the Cape of Good Hope.—Run from thence to the Islands of St. Helena and Ascension.

[edit]At the Cape of Good Hope, they are restored to full health and hear news from Europe. They go on some excursions while the ship is repaired. A German stowaway is found on board, who is first punished, then allowed to stay. They sail on to Saint Helena, where Cook learns of its incorrect description by Hawkesworth. They are invited by the governor and to a ball. The next stop is Ascension, which Forster finds dreary. They encounter a ship from New York and catch turtles for food.

Chapter VIII. Run from Ascension, past the Island of Fernando da Noronha, to the Açores.—Stay at Fayal.—Return to England.

[edit]From Ascension, they sail west, coming in sight of Fernando de Noronha and exchanging salutes with forts there. They cross the equator after two years and nine months in the Southern hemisphere. Their next stop is the Azores, where they anchor at Fayal, and visit the town of Horta, where they stay in the house of the deputy consul. Forster proceeds to describe the Azores. They soon continue to England.

Thus, after escaping innumerable dangers, and suffering a long series of hardships, we happily completed a voyage, which had lasted three years and sixteen days; in the course of which, it is computed we run over a greater space of sea than any ship ever did before us; since, taking all our tracks together, they form more than thrice the circumference of the globe. We were likewise fortunate enough to lose only four men; three of whom died by accident, and one by a disease, which would perhaps have brought him to the grave much sooner had he continued in England. The principal view of our expedition, the search after a southern continent within the bounds of the temperate zone, was fulfilled; we had even searched the frozen seas of the opposite hemisphere, within the antarctic circle, without meeting with that vast tract of land which had formerly been supposed to exist.[90]

Reception and influence

[edit]Contemporary reviews

[edit]While it did not sell well, Voyage was well received critically in Britain, with many favourable reviews,[91] some of which included quotations from both Forster's and Cook's report that demonstrated the superior style of the former.[92] For example, the Critical Review found fault with many mistakes in the engravings in Cook's book and with Cook's inclusion of nautical details, and after presenting lengthy sections where Forster's presentation is superior, concluded, "We now leave the reader to judge for himself on the merits of each of these performances".[93] In the Monthly Review, an author identified by Robert L. Kahn, the editor of the 1968 edition of Voyage, as William Bewley[94] reviewed Voyage in the April and June issues, mostly summarizing the Preface in April[95] and of the rest of the voyage in June.[96] The reviewer concludes by "acknowledging the pleasure we have received from the perusal of this amusing and well-written journal; which is rendered every where interesting by the pleasing manner in which the Author relates the various incidents of the voyage in general; as well as those which occurred to himself, in particular, during his several botanical excursions into the country".[96] In The Lady's Magazine, two anonymous "Letters to the Editor" are followed by excerpts, first from Forster's Tahiti episode,[97] then from Cook's and Forster's description of the arrival at Middelburg Island.[98] The letter-writer praises Forster's writing and the engravings in Cook's work, concluding: "In our opinion it is worth every gentleman's while to purchase both, in order to compare the prints of the one, with the descriptions of the other; but where one must be rejected, the choice of the reader will fall on Mr. Forster's narrative, whilst those who delight in pretty pictures, will prefer Cook's."[98]

Two opinions of other readers are known.[99] James Boswell spoke favourably of the book, while Samuel Johnson was less impressed:

I talked to him of Forster's Voyage to the South Seas, which pleased me; but I found he did not like it. 'Sir, (said he,) there is a great affectation of fine writing in it.' BOSWELL. 'But he carries you along with him.' JOHNSON. 'No, Sir; he does not carry ME along with him: he leaves me behind him: or rather, indeed, he sets me before him; for he makes me turn over many leaves at a time.'

Post-publication controversy

[edit]

William Wales, who had been the astronomer on board the Resolution, took offence at the word "was" in the statement that "[Arnold's watch] was unfortunately stopped immediately after our departure from New Zeeland in June 1773",[101] reading it as a claim that he as the keeper of the watch had deliberately sabotaged it. An exchange of letters ensued, with Wales asking for a recantation.[102] Wales, who had quarrelled with Reinhold on the voyage, later published what the editor of Cook's journals, John Beaglehole called "an octavo pamphlet of 110 indignant pages"[103] attacking the Forsters. In this book, Remarks on Mr Forster's Account of Captain Cook's last Voyage round the World,[104] Wales considered Johann Reinhold Forster to be the true author,[48][105][106] and accused him of lies and misrepresentations.[107] Georg Forster responded with a Reply to Mr Wales's Remarks,[108] containing some factual corrections and defending his father against the attacks. He claimed Wales was motivated by jealousy or acting on behalf of Sandwich.[109] In June 1778, this was followed up by a Letter to the Right Honourable the Earl of Sandwich, portraying Reinhold as victim of Sandwich's malice and claiming that the latter's mistress, Martha Ray, had caused this. The letter also apportioned blame to Barrington, and openly questioned his mistaken belief that sea water could not freeze.[110][111][nb 4] After this publication, there was no more possibility of reconciliation with the Admiralty, and the Forsters worked on plans to move to Germany.[113]

Authorship

[edit]The extent of Georg's authorship of Voyage continued to be a subject of debate after Wales's attacks. Beaglehole refers to Georg's claims of originality as "not strictly truthful" in his biography of Cook.[62] Kahn calls the book a "family enterprise" and a joint work based on Reinhold's journals, stating "probably sixty percent of it was finally written by George".[114] According to Leslie Bodi, the style and philosophy both point towards Georg.[105] Thomas P. Saine similarly states in his biography of Georg Forster that the quality of the English writing is too good to be Reinhold's work, and the comments and observations "reveal more of the youthful enthusiasm and attitude to be expected from Georg than of the more scientific temperament to be expected of Reinhold".[115] In her 1973 thesis, which has been described as the most reliable account of the history of writing and publication of Voyage,[116] Ruth Dawson describes the style of the work as "convincing evidence" for Georg's authorship and notes that his father was "involved in other matters" during the six months of writing.[117] On sources, she states: "While the role which J. R. Forster personally played in the writing of Voyage round the World and Reise um die Welt is a limited one, his records are the major source for almost all the facts and events described."[118] Her overall conclusion is: "It seems certain however that it was Georg Forster who wrote the account."[119] Philip Edwards, while pointing out many observations that clearly are Georg's, calls Voyage a "collaborative, consensual work; a single author has been created out of the two minds involved in the composition".[120] Nicholas Thomas and Oliver Berghof, the editors of the 2000 edition, find Kahn's conclusions unpersuasive and state the text is "in effect an independent account, an additional source for the events of Cook's second voyage, rather than simply a revised version of another primary source", differentiating Voyage from earlier publications where Georg had been his father's assistant.[121]

Translations

[edit]

Georg Forster and Rudolf Erich Raspe translated the book into German as Reise um die Welt.[122] The translation included some additional material taken from Cook's report.[123] After publication of the German edition, excerpts of which were published in Wieland's influential journal Der Teutsche Merkur, both Forsters became famous, especially Georg, who was celebrated upon his arrival in Germany.[124][125] Reise um die Welt let Georg Forster become one of the most widely read writers in Germany.[126][127] Both Forsters eventually obtained professorships in Germany: Georg at the Collegium Carolinum in Kassel in 1778 and his father at Halle in 1780.[128] The first German edition, published by Haude und Spener in Berlin in two volumes in 1778 and 1780,[129] sold out in 1782 and was followed by a second edition in 1784, and has become a classic of travel literature, reprinted in many editions.[130][nb 5] Voyage was also translated into other European languages. Before 1800, translations into Danish,[132] French, Russian, and Swedish appeared; additionally, a Spanish translation contained parts of Cook's official account.[133]

Influence

[edit]

Georg Forster and his works, especially Voyage, had a great influence on Alexander von Humboldt and his Voyage aux régions equinoxiales du Nouveau Continent (Personal Narrative of Travels to the Equinoctial Regions of the New Continent).[134] In the article on Georg Forster in the 9th edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica, Richard Garnett wrote about Voyage: "His account of Cook's voyage is almost the first example of the glowing yet faithful description of natural phenomena which has since made a knowledge of them the common property of the educated world, a prelude to Humboldt, as Humboldt to Darwin and Wallace."[135][136] Humboldt himself wrote about Forster, "through him has been commenced a new era of scientific travelling, having for its object the comparative knowledge of nations and of nature in different parts of the earth's surface".[137]

The book has been studied as one of the sources for Samuel Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner, which according to the Australian academic Bernard Smith has been influenced by reports of Cook's second journey including Forster's, possibly because William Wales was one of Coleridge's teachers at Christ's Hospital.[138] The literary scholar Arnd Bohm even goes as far as claiming that there are "details of imagery and wording that suggest Forster as the strongest influence".[139]

Modern reception

[edit]There has been a large body of literature studying Voyage since the 1950s,[140] including the PhD thesis of Ruth Dawson,[141] which contains the most extensive account of the genesis of the text.[142] The most widely studied part of the work is the content relating to Tahiti.[143] Despite making up less than five per cent of the text, almost half of the literature about Voyage has focused exclusively on this part of the journey, often studying Forster's comparisons of European and Tahitian culture and of civilisation and nature.[144] Other authors portrayed his moral disdain for Tahitian sexual indulgence as European self-discipline,[145] in contrast to the first reports about Tahiti by French explorer Louis Antoine de Bougainville that had started the European perception of the South Pacific as a place of sexual freedom.[146]

In the 1968 edition, the first English edition since the 18th century, part of the East German Academy of Sciences' edition of Forster's collected works, Kahn found high praise for his subject, stating: "I consider the Voyage to be the finest work with regard to style and presentation to come out of the three expeditions of Cook and one of the greatest travelogues written in any tongue or age."[147]

The 2000 edition was well received by critics. In his review of it, the anthropologist John Barker praises both Forster's "marvelous narrative" and the editors and ends "... modern scholars, Pacific islanders and casual readers alike are greatly in their debt for bringing this wonderful text out of the archives and making it available in this beautifully produced edition".[148] The historian Kay Saunders notes the "ethnographic sophistication that was in many respects remarkably free of contemporary Eurocentrism", and praises the editors, stating "commentary over such a vast range of disciplines that defy modern scholarly practice requires an extraordinary degree of competency".[149] The welcoming review of historian Alan Frost discusses the importance of Cook's second journey at length. Forster's writing is described as the "most lyrical of all the large narratives of Europe's reconnaissance of the Pacific", but also "stilted and his literary analogies too frequent and forced".[150] The historian Paul Turnbull notes the book has been "overshadowed for 200 years by Cook's lavishly illustrated account" and praises the editors, contrasting their approach against received Eurocentric Cook scholarship.[151] The anthropologist Roger Neich, calling the edition "magnificent", comments that the "narrative initiated a stage in the evolution of travel writing as a literary genre, representing an insightful empiricism and empathy showing that the 'Noble Savage' was not a complete description".[152] The cultural historian Rod Edmond, while calling Cook's report "often dull" and Reinhold Forster's Observations "a meditation on the voyage but not the thing itself", states the book "combines the immediacy of experience with developed reflection upon it, and is much better written than anything by either Cook or his own father".[153] The review of James C. Hamilton, a historian and Cook scholar, states: "George Forster's enjoyable narrative serves as a valuable record of the Second Voyage and a useful reference for persons interested in Captain Cook."[70]

English editions

[edit]Other than an unauthorised reprint of both Cook's and Forster's reports that appeared in Dublin in 1777, the book was not reprinted in English for almost two centuries.[nb 6] In 1968, it appeared (edited by the Rice University professor of German studies Robert L. Kahn) as the first volume of an edition of Forster's collected works, published by the East German Akademie-Verlag. Finally, in 2000 the University of Hawaiʻi Press published an edition by Nicholas Thomas and Oliver Berghof.[155] The list of all editions is as follows:

- Forster, George (1777). A Voyage Round the World: In His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. I. London: B. White.

- Forster, George (1777). A Voyage Round the World: In His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. II. London: B. White.

- Cook, James; Forster, Georg (1777). A voyage round the world, performed in His Britannic Majesty's ships the Resolution and Adventure, in the years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. Dublin: Printed for W. Whitestone, S. Watson, R. Cross, J. Potts, J. Hoey, L.L. Flin, J. Williams, W. Colles, W. Wilson, R. Moncrieffe, T. Armitage, T. Walker, C. Jenkin, W. Hallhead, G. Burnett, J. Exshaw, L. White, and J. Beatty. OCLC 509240258.

- Forster, Georg (1968). Kahn, R. L. (ed.). Werke: A voyage round the world. Akademie-Verlag. OCLC 310001820.

- Forster, George (2000). Thomas, Nicholas; Berghof, Oliver (eds.). A voyage round the world. Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. ISBN 9780824861308. JSTOR j.ctvvn739. OCLC 70765538.

Notes

[edit]- ^ Forster, whose full name was Johann George Adam Forster, is known both as "George Forster" and as "Georg Forster". The German form of his name is also common in English (for example, Thomas P. Saine's English-language biography is titled Georg Forster),[1] which helps to distinguish him from George Forster, a contemporaneous English traveller.[2]

- ^ "No man lost by sickness" was not completely correct: The marine Isaac Taylor, who had been afflicted with consumption since the departure from England, died on Tahiti in August 1773.[32] Cook's own journal stated "I lost but four men and only one of them by sickness."[30][33]

- ^ Despite the Latin title, which means "Observations on natural history, begun by G. F. in July 1772 on a voyage to the southern lands", this memorandum is written in English. It is reprinted in Volume IV of Georg Forster's collected works.[56]

- ^ Barrington, like the Swiss geographer Samuel Engel, claimed that the ice found in the sea was not frozen sea water, but came from the rivers breaking up each summer.[112]

- ^ The 1970 Bibliography of Captain James Cook additionally lists German editions appearing in 1785–89, 1922, 1926, 1960, 1963, and 1965–66.[131]

- ^ Many excerpts and summaries were published that were based on Voyage, often combined with parts of Cook's account, some of them listed by Kahn.[154]

References

[edit]Footnotes

[edit]- ^ Saine 1972.

- ^ Rosove 2015.

- ^ a b Engledow 2009.

- ^ Mariss 2019, p. 166.

- ^ Beaglehole 1992, p. viii.

- ^ Wilke 2013, p. 265.

- ^ Royal Academy 1781, p. 5.

- ^ Hough 2003, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Beaglehole 1968, p. cv.

- ^ Nicandri 2020, p. 50.

- ^ Nicandri 2020, p. 80.

- ^ Saine 1972, p. 21.

- ^ O'Brian 1997, p. 156.

- ^ Hoare 1982, p. 49.

- ^ a b Hoare 1976, p. 73.

- ^ Hoare 1982, p. 48.

- ^ Paisey 2011, p. 111.

- ^ Steiner 1977, p. 13.

- ^ Rosove 2015, p. 611.

- ^ Hoare 1982, pp. 43–46.

- ^ Hoare 1982, pp. 50–51.

- ^ O'Brian 1997, p. 160.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 681.

- ^ Hoare 1976, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Gordon 1975, pp. 155–157.

- ^ Hoare 1982, p. 69.

- ^ Thomas & Berghof 2000, p. xix.

- ^ Beaglehole 1969, pp. xlix–l.

- ^ Beaglehole 1969, p. lxii.

- ^ a b Beaglehole 1992, p. 441.

- ^ Hoare 1982, p. 58.

- ^ Beaglehole 1969, p. 200.

- ^ Beaglehole 1969, p. 682.

- ^ Abbott 1970, p. 341.

- ^ Edwards 2004, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Görbert 2020, p. 248.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 88.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 112.

- ^ Williams 2013, pp. 113–114.

- ^ Beaglehole 1992, p. 465.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 160.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 161.

- ^ a b Hoare 1982, p. 66.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 18.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 162.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 119.

- ^ Saine 1972, p. 23.

- ^ a b c Thomas & Berghof 2000, p. xxviii.

- ^ Williams 2013, p. 114.

- ^ a b Joppien & Smith 1985, p. 107.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 34.

- ^ Görbert 2017, pp. 72–73, 78–80.

- ^ Dawson 1973, pp. 30–34.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 115.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 26.

- ^ Forster & Kahn 1989, pp. 93–107.

- ^ Görbert 2014, pp. 73–74.

- ^ Görbert 2015.

- ^ Goldstein 2019, p. 25.

- ^ Hoare 1967.

- ^ Thomas 2016, p. 102.

- ^ a b Beaglehole 1992, p. 470.

- ^ Feingold 2017, p. 212.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 698.

- ^ David 1992, pp. lxxx–lxxxii.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 169.

- ^ a b Enzensberger 1996, p. 87.

- ^ Thomas & Berghof 2000, p. xxvi.

- ^ Oberlies 2008.

- ^ a b Hamilton 2010.

- ^ Edwards 2004, p. 120.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. iv.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 36.

- ^ Forster 1777a, pp. 108–109.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 120.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 187.

- ^ Forster 1777a, pp. 211–212.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 253.

- ^ Forster 1777a, pp. 264–265.

- ^ Smith 1985, p. 74.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 488.

- ^ Forster 1777a, pp. 510–511.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 526.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 540.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 544.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 601.

- ^ Forster 1777b, p. 272.

- ^ Forster 1777b, p. 411.

- ^ Forster 1777b, p. 575.

- ^ Forster 1777b, pp. 604–605.

- ^ Williams 2013, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Kahn 1968, pp. 704–705.

- ^ Critical review 1777.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 703.

- ^ Bewley 1777a.

- ^ a b Bewley 1777b.

- ^ Lady's Magazine 1777a.

- ^ a b Lady's Magazine 1777b.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 700.

- ^ Boswell 1791, p. 161.

- ^ Forster 1777a, p. 554.

- ^ Hoare 1976, pp. 174–175.

- ^ Beaglehole 1969, pp. cli–clii.

- ^ Wales 1778.

- ^ a b Bodi 1959.

- ^ Wales 1778, p. 2.

- ^ Mariss 2019, p. 3.

- ^ Forster 1778.

- ^ Hoare 1976, p. 179.

- ^ Hoare 1976, pp. 179–180.

- ^ Thomas & Berghof 2000, p. xxvii.

- ^ Williams 2002, p. 323.

- ^ Uhlig 2004, p. 103.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 696-697.

- ^ Saine 1972, p. 24.

- ^ Peitsch 2001, p. 216.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 24.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 25.

- ^ Dawson 1973, p. 252.

- ^ Edwards 2004, pp. 115–116.

- ^ Thomas & Berghof 2000, pp. xxviii–xxix.

- ^ Harpprecht 1990, p. 180.

- ^ Görbert & Peitsch 2016, p. 136.

- ^ Uhlig 2004, p. 107.

- ^ Liebersohn 2005.

- ^ Steiner 1977, p. 22.

- ^ Hahn & Fischer 1993, p. 15.

- ^ Craig 1969.

- ^ Steiner 1977, p. 17.

- ^ Lepenies 1983.

- ^ Beddie 1970, pp. 230–232.

- ^ Beddie 1970, p. 231.

- ^ Kahn 1968, pp. 702–704.

- ^ Ackerknecht 1955.

- ^ Garnett 1879.

- ^ Merz 1896, p. 179.

- ^ Humboldt 1849, p. 70.

- ^ Smith 1956.

- ^ Bohm 1983.

- ^ Peitsch 2001, pp. 215–222.

- ^ Dawson 1973.

- ^ Görbert 2015, p. 2.

- ^ Görbert 2015, p. 1.

- ^ Peitsch 2001, pp. 219–220.

- ^ Peitsch 2001, pp. 220.

- ^ Zhang 2013, p. 271.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 677.

- ^ Barker 2001.

- ^ Saunders 2000.

- ^ Frost 2001.

- ^ Turnbull 2003.

- ^ Neich 2001.

- ^ Edmond 2001.

- ^ Kahn 1968, p. 701.

- ^ Thomas & Berghof 2000, p. xlv.

Sources

[edit]- Abbott, John L. (1970). "John Hawkesworth: Friend of Samuel Johnson and Editor of Captain Cook's Voyages and of the Gentleman's Magazine". Eighteenth-Century Studies. 3 (3): 339–350. doi:10.2307/2737875. ISSN 0013-2586. JSTOR 2737875.

- Ackerknecht, Erwin H. (1955). "George Forster, Alexander von Humboldt, and Ethnology". Isis. 46 (2): 83–95. doi:10.1086/348401. ISSN 0021-1753. JSTOR 227120. PMID 13242231. S2CID 26981757.

- Barker, John (2001). "Review of A Voyage Round the World. Volumes I & II". Pacific Affairs. 74 (4): 630–632. doi:10.2307/3557841. ISSN 0030-851X. JSTOR 3557841.

- Beaglehole, John C. (1968) [1955]. The journals of Captain James Cook: the voyage of the Endeavour, 1768–1771. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press : Hakluyt Society. OCLC 223185477.

- Beaglehole, John C. (1969) [1961]. The journals of Captain James Cook on his voyages of discovery. II. Cambridge: Published for the Hakluyt Society at the University Press. OCLC 1052665808.

- Beaglehole, J. C. (1 April 1992) [1974]. The Life of Captain James Cook. Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-8047-2009-0.

- Beddie, M. K (1970). Bibliography of Captain James Cook. Sydney: Council of the Library of New South Wales. ISBN 978-0-7240-9999-3. OCLC 1087403602.

- Bewley, William (April 1777a). "Art. X. A Voyage Round the World". The Monthly Review. LVI: 266–270.

- Bewley, William (June 1777b). "Art. VII. A Voyage Round the World". The Monthly Review. LVI: 456–467.

- Bodi, Leslie (1 May 1959). "Georg Forster: The 'Pacific expert' of eighteenth-century Germany". Historical Studies: Australia and New Zealand. 8 (32): 345–363. doi:10.1080/10314615908595136. ISSN 0728-6023.

- Bohm, Arnd (1983). "Georg Forster's A Voyage Round the World as a Source for The Rime of the Ancient Mariner: A Reconsideration". ELH. 50 (2): 363–377. doi:10.2307/2872821. ISSN 0013-8304. JSTOR 2872821.

- Boswell, James (1791). The Life of Samuel Johnson. Henry Baldwin.

- Craig, Gordon A. (1969). "Engagement and Neutrality in Germany: The Case of Georg Forster, 1754–94". The Journal of Modern History. 41 (1): 2–16. doi:10.1086/240344. ISSN 0022-2801. JSTOR 1876201. S2CID 143853614.

- David, Andrew (1992). The charts and coastal views of Captain Cook's voyages. Vol. 2. London: Hakluyt Society. ISBN 978-0-904180-31-2. OCLC 165493844.

- Dawson, Ruth (1973). Georg Forster's Reise um die Welt. A Travelogue in its Eighteenth-Century Context (PhD thesis). University of Michigan. OCLC 65229601.

- Edmond, Rod (November 2001). "A voyage round the world". Journal for Maritime Research. Archived from the original on 24 December 2004. Retrieved 4 September 2021.

- Edwards, Philip (20 May 2004). The Story of the Voyage: Sea-Narratives in Eighteenth-Century England. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-60426-0.

- Engledow, Sarah (1 December 2009). "To the end of the earth". Portrait. No. 34. ISSN 1446-3601.

- Feingold, Mordechai (25 July 2017). History of Universities: Volume XXX / 1–2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-253372-2.

- Enzensberger, Ulrich (1996). Georg Forster: ein Leben in Scherben (in German). Eichborn. ISBN 978-3-8218-4139-7.

- Forster, George (1777a). A Voyage Round the World: In His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. I. London: B. White.

- Forster, George (1777b). A Voyage Round the World: In His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, During the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5. Vol. II. London: B. White.

- Forster, Johann Georg Adam (1778). Reply to Mr Wales's Remarks. B. White.

- Forster, Georg; Kahn, Robert L (1989) [1972]. Georg Forsters Werke. 4. Streitschriften und Fragmente zur Weltreise. Berlin: Akad.-Verl. ISBN 978-3-05-000857-8. OCLC 312552078.

- Frost, Alan (2001). "Review of A Voyage Round the World: I and II". The International History Review. 23 (1): 144–148. ISSN 0707-5332. JSTOR 40108615.

- Garnett, Richard (1879). . Encyclopædia Britannica (Ninth ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons – via Wikisource.

- Goldstein, Jürgen (27 March 2019). Georg Forster: Voyager, Naturalist, Revolutionary. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-47481-6.

- Görbert, Johannes (2014). Die Vertextung der Welt: Forschungsreisen als Literatur bei Georg Forster, Alexander von Humboldt und Adelbert von Chamisso (in German). De Gruyter. pp. 73–74. ISBN 978-3-11-037411-7.

- Görbert, Johannes (12 January 2015). ""Ein Morgen war's, schöner hat ihn schwerlich je ein Dichter beschrieben." Zur Textgenese von Georg Forsters literarischer Tahiti-Inszenierung". Georg-Forster-Studien (in German). XX. Kassel University Press: 1–16. doi:10.19211/KUP9783737600576.

- Görbert, Johannes (2017). "Textgeflecht Dusky Bay. Varianten einer Weltumsegelung bei James Cook, Johann Reinhold und Georg Forster.". In Görbert, Johannes; Kumekawa, Mario; Schwarz, Thomas (eds.). Pazifikismus. Poetiken des Stillen Ozeans (in German). Würzburg: Königshausen & Neumann. pp. 71–95.

- Görbert, Johannes (7 September 2020). "James Cook and George Forster, Journals and Travel Reports from Their "Voyage Round the World" (1777)". In Schiff, Barbara (ed.). Handbook of British Travel Writing. De Gruyter. pp. 247–266. doi:10.1515/9783110498974-015. ISBN 978-3-11-049897-4. S2CID 243697496.

- Görbert, Johannes; Peitsch, Helmut (2016). "Georg Forsters Positionen zu James Cook.". In Knapp, Lore; Kronshage, Eike (eds.). Britisch-deutscher Literaturtransfer 1756–1832. De Gruyter. pp. 127–151. doi:10.1515/9783110498141-008. ISBN 978-3-11-050004-2.

- Gordon, Joseph Stuart (1975). Reinhold and Georg Forster in England, 1766–1780 (Thesis). Ann Arbor: Duke University. OCLC 732713365.

- Hahn, Andrea; Fischer, Bernhard (1993). "Alles ... von mir!: Therese Huber (1764–1829) (in German). Marbach am Neckar: Deutsche Schillergesellschaft. ISBN 3-929146-05-3. OCLC 231965804.

- Hamilton, James C. (2010). "A Voyage Round the World Forster, George. (Edited by Nicholas Thomas and Oliver Berghof, assisted by Jennifer Newell.) 2000". Cook's Log. 33 (3). The Captain Cook Society (CCS): 41. Archived from the original on 27 September 2019. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Harpprecht, Klaus (1990). Georg Forster oder Die Liebe zur Welt: eine Biographie (in German). Rowohlt Verlag. ISBN 978-3-499-12634-5.

- Hoare, M. E. (1967). "Johann Reinhold Forster: The Neglected 'Philosopher' of Cook's Second Voyage (1772–1775)". The Journal of Pacific History. 2: 215–224. doi:10.1080/00223346708572117. ISSN 0022-3344. JSTOR 25167919.

- Hoare, Michael Edward (1976). The Tactless Philosopher: Johann Reinhold Forster (1729–98). Hawthorne Press. ISBN 978-0-7256-0121-8.

- Hoare, Michael Edward (1982). The Resolution journal of Johann Reinhold Forster, 1772–1775. Hakluyt Society. ISBN 978-0-904180-10-7.

- Hough, Richard (2003). Captain James Cook. London: Coronet. ISBN 0-340-82556-1. OCLC 51106748.

- Humboldt, Alexander von (1849). Cosmos. Longmans & Murray.

- Joppien, Rüdiger; Smith, Bernard (1985). The art of Captain Cook's voyages. Vol. 2. Melbourne: Oxford University Press in association with the Australian Academy of the Humanities. ISBN 978-0-19-554456-5. OCLC 191992050.

- Kahn, R. L. (1968). "The History of the Work". Werke: A voyage round the world. By Forster, Georg. Kahn, R. L. (ed.). Akademie-Verlag. pp. 676–709. OCLC 310001820.

- Lepenies, Wolf (25 February 1983). "Georg Forster: Reise um die Welt". Die Zeit (in German). ISSN 0044-2070. Archived from the original on 9 January 2018. Retrieved 27 September 2019.

- Liebersohn, Harry (January 2005). "A Radical Intellectual with Captain Cook: George Forster's world voyage". Common-Place. Archived from the original on 6 July 2019. Retrieved 23 September 2019.

- Mariss, Anne (9 September 2019). Johann Reinhold Forster and the Making of Natural History on Cook's Second Voyage, 1772–1775. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-4985-5615-6.

- Merz, John Theodore (1896). A History of European Thought in the Nineteenth Century by John Theodore Merz. W. Blackwood and Sons.

- Neich, Roger (2001). "Review of A Voyage Round the World: George Forster. 2 vols". The Journal of the Polynesian Society. 110 (2): 225–227. ISSN 0032-4000. JSTOR 20706996.

- Nicandri, David L. (2020). Captain Cook Rediscovered: Voyaging to the Icy Latitudes. UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-7748-6222-6.

- Oberlies, Anke (April 2008). "Reise um die Welt: Illustriert von eigener Hand Forster, Georg. 2007". Cook's Log. 31 (2). The Captain Cook Society (CCS): 39. ISSN 1358-0639. Archived from the original on 25 September 2019. Retrieved 25 September 2019.

- O'Brian, Patrick (1997). Joseph Banks: A Life. Harvill Press. ISBN 978-1-86046-406-5.

- Paisey, David (1 September 2011). "Letters by Johann Reinhold Forster about Captain Cook's First Voyage and the Preparations for the Second". Terrae Incognitae. 43 (2): 99–133. doi:10.1179/008228811X13079576458410. ISSN 0082-2884. S2CID 170494865.

- Peitsch, Helmut (2001). Georg Forster: A History of His Critical Reception. P. Lang. pp. 215–222. ISBN 978-0-8204-4925-8.

- Rosove, Michael H. (2015). "The folio issues of the Forsters' Characteres Generum Plantarum (1775 and 1776): a census of copies". Polar Record. 51 (6): 611–623. Bibcode:2015PoRec..51..611R. doi:10.1017/S0032247414000722. ISSN 0032-2474. S2CID 129922206.

- Saine, Thomas P. (1972). Georg Forster. Twayne Publishers.

- Saunders, Kay (2000). "Book Reviews. George Forster, A Voyage around the World". Australian Journal of Politics & History. 46 (3): 428. doi:10.1111/1467-8497.00107. ISSN 1467-8497.

- Smith, Bernard (1956). "Coleridge's Ancient Mariner and Cook's Second Voyage". Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes. 19 (1/2): 117–154. doi:10.2307/750245. ISSN 0075-4390. JSTOR 750245. S2CID 192306717.

- Smith, Bernard (1985). European vision and the South Pacific. New Haven : Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-02815-7.

- Steiner, Gerhard (1977). Georg Forster (in German). Stuttgart: J.B. Metzler. ISBN 978-3-476-10156-3. OCLC 462099778.

- Thomas, Nicholas; Berghof, Oliver (2000). Introduction. A voyage round the world. By Forster, George. Thomas, Nicholas; Berghof, Oliver (eds.). Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press. pp. xix–xliii. ISBN 978-0-8248-6130-8. OCLC 70765538.

- Thomas, Nicholas (November 2016). "Part Two. 1772–1775.". The Voyages of Captain James Cook: The Illustrated Accounts of Three Epic Pacific Voyages. By Cook, James; Hawkesworth, John; Forster, Georg; King, James. Thomas, Nicholas (ed.). Voyageur Press. p. 102. ISBN 978-0-7603-5029-4.

- Turnbull, Paul (1 June 2003). "Book Reviews. A Voyage Round the World". The Journal of Pacific History. 38 (1): 137–146. doi:10.1080/00223340306075. ISSN 0022-3344. S2CID 219627361.

- Uhlig, Ludwig (2004). Georg Forster: Lebensabenteuer eines gelehrten Weltbürgers (1754–1794) (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 107. ISBN 978-3-525-36731-5.

- Wales, William (1778). Remarks on Mr. Forster's account of Captain Cook's last voyage round the world, in the years 1772, 1773, 1774, and 1775. By William Wales, F.R.S. Astronomer on Board the Resolution, in that Voyage, under the Appointment of the Board of Longitude. OCLC 836741035.

- Wilke, Sabine (2013). "Toward an Environmental Aesthetics: Depicting Nature in the Age of Goethe". Goethe's Ghosts: Reading and the Persistence of Literature. By Richter, Simon; Block, Richard A. Boydell & Brewer. pp. 262–275. ISBN 978-1-57113-567-4.

- Williams, Glyndwr (2002). Voyages of delusion : the Northwest Passage in the age of reason. London : HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-00-257181-4.

- Williams, Glyn (22 October 2013). Naturalists at Sea: Scientific Travellers from Dampier to Darwin. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-18073-2.

- Zhang, Chunjie (2013). "Georg Forster in Tahiti: Enlightenment, Sentiment and the Intrusion of the South Seas". Journal for Eighteenth-Century Studies. 36 (2): 263–277. doi:10.1111/j.1754-0208.2012.00545.x. ISSN 1754-0208.

- Critical review (1777). "Cook's and Forster's Voyage Round the World". The Critical Review, Or, Annals of Literature. 43: 370–380. hdl:2027/njp.32101045234745.

- Lady's Magazine (April 1777a). "Extract from Forster's Voyage". The Lady's Magazine Or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex: Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement. 8. Baldwin, Cradock & Joy: 193–197.

- Lady's Magazine (May 1777b). "Captain Cook's Account of his late Voyage". The Lady's Magazine Or Entertaining Companion for the Fair Sex: Appropriated Solely to Their Use and Amusement. 8. Baldwin, Cradock & Joy: 260–263.

- Royal Academy (1781). The exhibition of the Royal Academy, MDCCLXXXI. The thirteenth. London: T. Cadell.

External links

[edit]- Complete text at Digital Archives and Pacific Cultures.

- Scan and transcript of the German first edition: vol. 1, vol. 2