World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights

The World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights is a declaration of rights adopted in 1985 to protect sex workers' rights (or prostitutes' rights) worldwide.[1][2] It was adopted on 15 February 1985 at the first World Whores Congress in Amsterdam by the newly formed International Committee for Prostitutes' Rights (ICPR).[2][3] The Charter established a human rights-based approach to prostitution, demanding that sex workers be guaranteed freedom of speech, travel, immigration, work, marriage, motherhood, health, and housing, amongst other things.[4] This approach has subsequently been further elaborated by the sex workers' rights movement.[4]

Background[edit]

The World Charter emerged from the prostitutes' / sex workers' rights movement starting in the mid-1970s.[1] The distinction between voluntary and forced prostitution was developed by the movement in response to feminists and others who saw all prostitution as abusive. The World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights calls for the decriminalisation of "all aspects of adult prostitution resulting from individual decisions."[5] The World Charter further states that prostitutes should be guaranteed "all human rights and civil liberties", including the freedom of speech, travel, immigration, work, marriage, and motherhood, and the right to unemployment insurance, health insurance and housing.[6] Furthermore, the World Charter calls for protection of "work standards", including the abolition of laws which impose any systematic zoning of prostitution, and calls for prostitutes having the freedom to choose their place of work and residence, and to "provide their services under the conditions that are absolutely determined by themselves and no one else."[6] The World Charter calls for prostitutes to pay regular taxes "on the same basis as other independent contractors and employees," and to receive the same benefits for their taxes.[6]

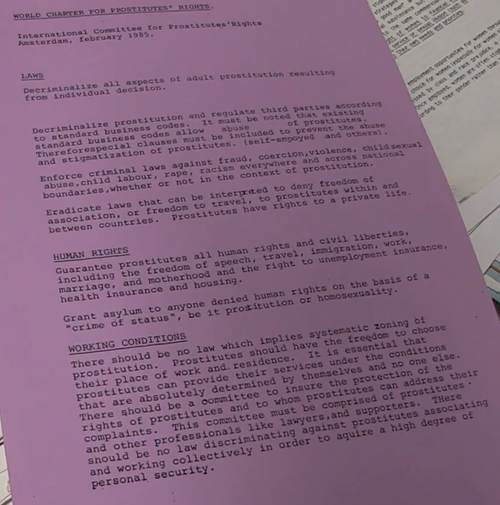

Text[edit]

- Decriminalize all aspects of adult prostitution resulting from individual decision.

- Decriminalize prostitution and regulate third parties according to standard business codes. Existing standard business codes allow abuse of prostitutes. Therefore, special clauses must be included to prevent the abuse and stigmatization of prostitutes (self-employed and others).

- Enforce criminal laws against fraud, coercion, violence, child sexual abuse, child labor, rape, racism everywhere and across national boundaries, whether or not in the context of prostitution.

- Eradicate laws that can be interpreted to deny freedom of association, or freedom to travel, to prostitutes within and between countries. Prostitutes have rights to a private life.

Human Rights

- Guarantee prostitutes all human rights and civil liberties, including the freedom of speech, travel, immigration, work, marriage, and motherhood and the right to unemployment insurance, health insurance and housing.

- Grant asylum to anyone denied human rights on the basis of a "crime of status," be it prostitution or homosexuality.

Working Conditions

- There should be no law which implies systematic zoning of prostitution. Prostitutes should have the freedom to choose their place of work and residence. It is essential that prostitutes can provide their services under the conditions that are absolutely determined by themselves and no one else.

- There should be a committee to insure the protection of the rights of the prostitutes and to whom prostitutes can address their complaints. This committee must be comprised of prostitutes and other professionals like lawyers and supporters.

- There should be no law discriminating against prostitutes associating and working collectively in order to acquire a high degree of personal security.

Health

- All women and men should be educated to periodical health screening for sexually transmitted diseases. Since health checks have historically been used to control and stigmatize prostitutes, and since adult prostitutes are generally even more aware of sexual health than others, mandatory checks for prostitutes are unacceptable unless they are mandatory for all sexually active people.

Services

- Employment, counseling, legal, and housing services for runaway children should be funded in order to prevent child prostitution and to promote child well-being and opportunity.

- Prostitutes must have the same social benefits as all other citizens according to the different regulations in different countries.

- Shelters and services for working prostitutes and re-training programs for prostitutes wishing to leave the life should be funded.

Taxes

- No special taxes should be levied on prostitutes or prostitute businesses.

- Prostitutes should pay regular taxes on the same basis as other independent contractors and employees, and should receive the same benefits.

Public Opinion

- Support educational programs to change social attitudes which stigmatize and discriminate against prostitutes and ex-prostitutes of any race, gender or nationality.

- Develop educational programs which help the public to understand that the customer plays a crucial role in the prostitution phenomenon, this role being generally ignored. The customer, like the prostitute, should not, however, be criminalized or condemned on a moral basis.

- We are in solidarity with workers in the sex industry.

Organization

- Organizations of prostitutes and ex-prostitutes should be supported to further implementation of the above charter.

Impact[edit]

In an article announcing the adoption of the World Charter, the United Press International reported: "Women from the world's oldest profession, some wearing exotic masks to protect their identity, appealed Friday at the world's first international prostitutes' convention for society to stop treating them like criminals."[8][dead link][citation needed]

Support: development of a human rights approach[edit]

The World Charter, together with the two World Whores Congresses held in Amsterdam (February 1985) and Brussels (October 1986), epitomised a worldwide prostitutes' rights movement and politics.[1][9] The Charter established a human rights-based approach to prostitution, which has subsequently been further elaborated by the sex workers' rights movement.[4]

In 1999, the Santa Monica Mirror commented on the popularization of the term "sex worker" as an alternative to "whore" or "prostitute" and credited the World Charter, among others, for having "articulated a global political movement seeking recognition and social change."[10]

In 2000, the Carnegie Council published a report commenting on the results of the World Charter, fifteen years after its adoption.[4] The report concluded that the human rights approach embodied in the World Charter had proven "extremely useful for advocates seeking to reduce discrimination against sex workers."[4] For example, human rights advocates in Australia utilized the language of human rights to resist "mandatory health tests" for sex workers and to require that information regarding health be kept confidential.[4] However, the report also found that efforts from anti-prostitution activists to define prostitution (as a whole) as a human rights abuse might open the way some governments to try and "abolish the sex industry".[4]

And in 2003, Kimberly Klinger in The Humanist noted that the World Charter had become "a template used by human rights groups all over the world."[11]

Opposition[edit]

In other circles, the World Charter was initially met with scepticism and ridicule. The Philadelphia Daily News asked, "Does it contain a layoff clause?"[12] Another writer referred to it derisively as "a Magna Carta for whores".[13] When the second World Whores Congress was held in Brussels in 1986, Time reported: "Just what were all those hookers doing in the hallowed halls of the European Parliament in Brussels last week? The moral outrage echoing in the corridors may have suggested that a re-creation of Sodom and Gomorrah was being staged. Reason: about 125 prostitutes, including three men, were attending the Second World Whores Congress."[9]

The Charter remains controversial, as some feminists consider prostitution to be one of the most serious problems facing women, particularly in developing countries. In Jessica Spector's 2006 book Prostitution and Pornography, Vednita Carter and Evelina Giobbe offer the following critique of the Charter:

"Pretending prostitution is a job like any other job would be laughable if it weren't so serious. Leading marginalized prostituted women to believe that decriminalization would materially change anything substantive in their lives as prostitutes is dangerous and irresponsible. There are no liberating clauses in the World Charter. Pimps are not 'third party managers.'"[14]

See also[edit]

- A Vindication of the Rights of Whores

- COYOTE

- Decriminalisation of sex work

- International Day to End Violence Against Sex Workers

- Margo St. James

- Sex workers' rights

- Sex worker

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Kempadoo & Doezema 1998, p. 19–20.

- ^ a b c Ditmore 2006, p. 625.

- ^ Wotton 2016, p. 66–67.

- ^ a b c d e f g Saunders 2000.

- ^ Kempadoo & Doezema 1998, p. 37.

- ^ a b c [1] World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights

- ^ International Committee for Prostitutes' Rights (ICPR), Amsterdam 1985, Published in Pheterson, G (ed.), A Vindication of the Rights of Whores. Seattle: Seal Press, 1989. (p.40)

- ^ "Prostitutes Appeal For Decriminalization". St. Petersburg Times. 16 February 1986.

- ^ a b "World Notes Belgium". Time. 13 October 2006. Archived from the original on 21 December 2008.

- ^ Amalia Cabezos (4 August 1999). "Hookers in the House of the Lord". Santa Monica Mirror. Archived from the original on 20 August 2008.

- ^ Kimberly Klinger (January–February 2003). "Prostitution humanism and a woman's choice – Perspectives on Prostitution". The Humanist. American Humanist Association. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- ^ "Does It Contain A Layoff Clause?". Philadelphia Daily News. 15 February 1985.

- ^ "House of ill repute". The Daily Pennsylvanian. 6 March 1996.

- ^ Jessica Spector, ed. (2006). Prostitution and Pornography: Philosophical Debate about the Sex Industry, p. 35. Stanford University Press. ISBN 0-8047-4938-8.

Bibliography[edit]

- Ditmore, Melissa Hope (2006). Encyclopedia of Prostitution and Sex Work. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 782. ISBN 0-313-32968-0.

- Kempadoo, Kamala; Doezema, Jo (1998). Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance, and Redefinition. Routledge. p. 294. ISBN 9780415918299.

- Saunders, Penelope (6 August 2000). "Fifteen Years after the World Charter for Prostitutes' Rights". Human Rights Dialogue (1994–2005). 2 (3). Carnegie Council. Retrieved 11 December 2022.

- Wotton, Rachel (September 2016). "Sex workers who provide services to clients with disability in New South Wales, Australia" (PDF). ses.library.usyd.edu.au. University of Sydney. Retrieved 10 December 2022.