Wikipedia:Reference desk/Archives/Science/2012 November 8

| Science desk | ||

|---|---|---|

| < November 7 | << Oct | November | Dec >> | November 9 > |

| Welcome to the Wikipedia Science Reference Desk Archives |

|---|

| The page you are currently viewing is an archive page. While you can leave answers for any questions shown below, please ask new questions on one of the current reference desk pages. |

November 8[edit]

Melatonin[edit]

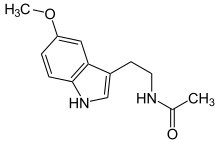

I am unclear in reading the article on Melatonin about its chemical properties:

- Is the carbon ring structure an aromatic/benzene ring, or just alternating single/double bonds?

- Is there a name for the structure of the carbon rings, the one similar to purine but not a purine?

- Is melatonin technically an ether?

- Is melatonin technically a ketone?

75.73.226.36 (talk) 02:25, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- The ring is aromatic, via Hückel's rule any ring is aromatic if it is planar and has 4n+2 electrons which can participate in pi-bonding. That fused 6-and-5 member rings with the nitrogen on the 5 membered ring has 10 pi-electrons (8 via double bonds, and 2 from the lone pair on nitrogen), which meets Hückel's rule (4*2+2 = 10). That ring structure is called Indole. There is an ether (the methoxy group attached to the indole) but there isn't a ketone group. The carbonyl attached to the amine is actually called an amide. --Jayron32 02:35, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- OK, I should have known about the amide factor. And I'm used to seeing aromatic rings as a circle within a hexagon. Is there any distinctive properties of melatonin that it gets from having the amide and ether groups? I am aware that the indole formation comes from the fact that it derives from the neurotransmitter serotonin. What makes it different? 75.73.226.36 (talk) 02:42, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Have a look at the Melatonin receptor agonist article. The "Structure-activity relationship (SAR)" section talks about the effect of various structural changes, which tells you about the possible roles of the parts of the structure, and the "Binding and pharmacophore" section talks in more detail about those roles. DMacks (talk) 02:49, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- OK, I should have known about the amide factor. And I'm used to seeing aromatic rings as a circle within a hexagon. Is there any distinctive properties of melatonin that it gets from having the amide and ether groups? I am aware that the indole formation comes from the fact that it derives from the neurotransmitter serotonin. What makes it different? 75.73.226.36 (talk) 02:42, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- More questions this raises! I see how ramelteon acts to promote melatonin reception, slightly, but now I have run into a

new mystery. What is the term for the dotted-line bond between the tricyclic carbon formation and the rest of the compound? I know some stuff about organic chemistry but this is new and unclear to me. Is there any specific factors this bond plays in ramelteon? 75.73.226.36 (talk) 03:08, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- See Skeletal structure#Stereochemistry for what this notation means. I have no idea what biochemical effect this specific stereochemistry plays, but given the synthesis of the drug, "it's almost certainly important" because the route appears to go to special effort to pick this particular one. DMacks (talk) 03:14, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Thank you much! However, why don't more molecules include stereochemical markings in their structural diagrams? You can't tell me that all other molecules are two-dimensional. Are these connected to stereoisomers; that is, would solely a change in the direction of the stereo-bond change the chemical identity of the substance? 75.73.226.36 (talk) 03:22, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- In biologically active molecules, stereochemistry always matters. Levomethamphetamine is a nasal decongestant. Dextromethamphetamine is speed. The difference is the stereochemistry around the one stereogenic carbon. In melatonin, there are no stereogenic carbons, so you don't see any dashes or wedges. In Ramelteon there is a stereogenic carbon, and it matters, so it is shown as a dash (away from the viewer). --Jayron32 05:59, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- The markings for stereochemistry are only shown when they're relevant. If you look at the article on isobutane, the very simple formula at top is all that is used by normal standards. The one at bottom with all the hydrogens depicted is more for teaching, and even that doesn't bother to show which hydrogens are pointed toward you or away. That's because all those bonds can move - the molecule is achiral. It takes specific circumstances for the conformation to matter, such as a double bond that doesn't freely rotate, or the existence of a chiral center with four different ligands that can't be mirror-imaged onto itself. Wnt (talk) 16:47, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- In biologically active molecules, stereochemistry always matters. Levomethamphetamine is a nasal decongestant. Dextromethamphetamine is speed. The difference is the stereochemistry around the one stereogenic carbon. In melatonin, there are no stereogenic carbons, so you don't see any dashes or wedges. In Ramelteon there is a stereogenic carbon, and it matters, so it is shown as a dash (away from the viewer). --Jayron32 05:59, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Thank you much! However, why don't more molecules include stereochemical markings in their structural diagrams? You can't tell me that all other molecules are two-dimensional. Are these connected to stereoisomers; that is, would solely a change in the direction of the stereo-bond change the chemical identity of the substance? 75.73.226.36 (talk) 03:22, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- See Skeletal structure#Stereochemistry for what this notation means. I have no idea what biochemical effect this specific stereochemistry plays, but given the synthesis of the drug, "it's almost certainly important" because the route appears to go to special effort to pick this particular one. DMacks (talk) 03:14, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Proposed Essay on zealotry and non-science[edit]

I would like to post an essay on this with reference to global warming and passive smoking. It there someone who could read this essay, advise if the subject has been covered before etc? Thanks in advance SmokeyTheCat 12:56, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Please read Wikipedia:What Wikipedia is not#Wikipedia is not a publisher of original thought, especially item #3, as well as Wikipedia:No original research#Synthesis of published material that advances a position. Your proposed article sounds like it would run afoul of either of these long-standing and strongly enforced Wikipedia content policies. --Jayron32 14:43, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Hmmm... it sounds like he's asking for a list of possible reviewers. Now to begin with, if the essay is descriptive of sources rather than personal opinion, and if you're willing to release it for copying and modification by anyone, it might be Wikipedia material, (or at least Wikiversity material. :) ) If not, we have a List of internet forums that is much less than satisfactory - it doesn't mention http://www.physicsforums.com for example (though I doubt that's quite what you want). Somebody help me out here - there must be a good resource listing lots of options for serious writers of pieces like this. Wnt (talk) 17:27, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- If you publish it on your blog, and announce it in a suitable place, I trust you'll get at least a few comments. —Tamfang (talk) 19:55, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Actually this http://www.numberwatch.co.uk/religion.htm says most what I was proposing to say about global warming. SmokeyTheCat 06:04, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Law of Conservation of Energy[edit]

I suppose such things would be improbably constructed in real life, but couldn't water be pumped to height X and then allowed to travel on an exceedingly long track of slide so as to trigger/interact with so very many water wheels etc. that more power is generated than it took to raise the water to the height X? Or is the universe constructed in a way such that, by definition, the conditions of the track of slide I propose (i.e. its relative lack of slope, etc.) would counteract my proposal by causing the water to proceed so slowly that little energy is produced because the wheels barely move. I'm not a formula guy, but is it this sort of logical manner of understanding the problem a good reason for why this won't work? DRosenbach (Talk | Contribs) 13:16, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, each wheel slows down the water so that the net effect is that significantly less energy is generated than the amount used to pump up the water. The only way you can get "more than 100% back" is to pump the water up at high tide and release it at low tide, though the "extra energy" in this case ultimately comes from the combined kinetic and potential energy of the earth-moon system. Dbfirs 13:40, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- (ec) I think you answered your own question quite well. The mechanical work that is done by a force on an object depends only on the distance that the object travels in the direction of the force. So because gravity pulls objects downwards, only the vertical component of the distance traveled can be converted to mechanical energy. Whether gravity works directly on the water, giving it speed, or whether the water transfers that work to e.g. a wheel does not matter here. - Lindert (talk) 13:45, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Eventually, the water will be slowed so much by interacting with each wheel that it cannot turn the lower wheels at all, and starts to spill over the edge of its trough. AlexTiefling (talk) 14:43, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- And if you're hoping that each wheel is so small that its effect on the flow is negligible, that is unfortunately not the case. Suppose you make each wheel as small as you like. The amount of effect it has on the flow is subsequently "very small" - and so is the energy it can collect. Now, add up each miniscule contribution for each of your zillions of tiny waterwheels... and we've stumbled on the limit definition of the integral, without using any squiggly symbols. The mathematically-inclined observer will quickly make several critical observations: even very small quantities have a magnitude, and that magnitude can be compared to other very small quantities; and we've stumbled onto an epsilon-delta proof that no matter how small you make your water wheel paddles, they will each lose more energy than they gain. When you add up a large number of these water paddles, your total system cannot get more energy than its input. If you like to phrase it in this way, these mathematical facts correspond to physical observables; but the mathematics follow directly from our most fundamental axioms: in other words, most of us believe the universe is "constructed" in such a way that these facts cannot be incorrect (even if it takes a good deal of mental wrangling to deduce the consequences from first principles).

- Incidentally, this is the argument I use to refute the apparent thermodynamic conundrum of Maxwell's demon. No matter how small you make the demon, his gate has to be larger than the atoms he wishes to trap. (Put another way, his potential energy barrier must be larger than the energy of the molecules). Therefore, each time he opens or closes the door, the demon must expend more energy than he recuperates using his "paradoxical" thermodynamic trap. The laws of thermodynamics are circumvented when you conveniently forget to count the lossy parts of the system - no matter how small the individual losses, they add up! Feynman elaborates on this model by endowing the door with Brownian motion, once again solidly demonstrating that the rules of thermodynamics - including conservation of energy in a closed system - are consequences of statistical mechanics and cannot be beaten. Nimur (talk) 15:27, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Jeuming tree[edit]

In a poem by China's 8th-century poet, Du Fu (or Tu Fu), translated into English as "Autumn Rains Lament 1," the subject of the poem is a man trying to save his 'jeuming tree' from being uprooted by winds. In various translations of the poem, 'jeuming tree' is the agreed-upon translated spelling. Yet, I can't find it either in my desk dictionary or in Wikipedia, "Flora of China."

Would you kindly locate and provide me with an online source for this tree?Speer46 (talk) 14:41, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Thank you, Stanton Hager

- This is a hard one to answer properly.

- 阶下决明颜色鲜 jiē xià jué míng yán sè xiān

- 著叶满枝翠羽盖 zhù yè mǎn zhī cuì yǔ gài

- 开花无数黄金钱 kāi huā wú shù huáng jīn qián

- Below the steps, the jueming's colour is fresh.

- Full green leaves cover the stems like feathers,

- And countless flowers bloom like golden coins.[1]

- 决明 is related to the genus Cassia (as confirmed by our zh.wikipedia entry [2] ) However, these are ill-defined groupings of plants. I am immensely tempted to point at the Golden Shower Tree (Cassia fistula, above) which is widely distributed and loved for its beauty [3], and sometimes flowers in fall [4] - however, the general location of Xi'an is at best marginal for growing it. (Then again, that might be the point) However, it is completely irresponsible for me to do so since it could really be one of hundreds of species of Cassia, Cinnamomum, or Senna. Wnt (talk) 16:07, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Not sure if this is the same, but List of kampo herbs identifies 決明子 (jué míng zǐ)as Senna obtusifolia. That article also quotes the same poem. (Disclaimer: I have zero knowledge of Chinese). - Lindert (talk) 16:25, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- The wikt:子 is just "seed", the part used for that application; it's one of the many forms of "cassia" (maybe the same as Cassia tora, Senna tora, etcetera, maybe not). But looking at this I just don't feel poetic. Wnt (talk) 16:38, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Not sure if this is the same, but List of kampo herbs identifies 決明子 (jué míng zǐ)as Senna obtusifolia. That article also quotes the same poem. (Disclaimer: I have zero knowledge of Chinese). - Lindert (talk) 16:25, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- I'm not sure if this is any help. It apparently quotes the poem above and has some nice pictures of flowers - a bit more like "golden coins" than the one shown above. Alansplodge (talk) 17:28, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Hmmm... some things mentioned:

- 野决明 (wild cassia) = Thermopsis lupinoides (Linn.) [5]

- 西决明 (western cassia) or 望江南 (looks like cassia) = Cassia occidentalis L. [6] vs. [7]

- 茳芒决明 = Senna sophera [8] (ARS: [9])

- 槐叶决明 = Senna sophera [10]

Hmmm.... I'm seeing more shrubs and weeds here than trees. What I don't see is an answer about what this tree actually was. Indeed, the bottom line is that unless he mentioned it somewhere else, all we have is a poem about "cassia", and the precise nature of that is unobtainable. In the lack of a way to reason it out with any confidence, I'm going to stick to my perhaps poetic notion of it being a heroic effort to grow a Golden Shower Tree in Xi'an, even though the average low temperature in Xi'an is 21 F [11] and the seeds are only sold rated for Hardiness Zone 9b which has a minimum of 25 F minimum (i.e. central Florida) [12] or maybe even 10a [13]. To me the beauty of the plant and the difficulty of keeping one would seem to justify the poem. Wnt (talk) 19:02, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Please help a new owner of a United Motors Matrix 150 motor-scooter?[edit]

| Please don't post the same question on multiple desks. Any further responses will be added to the section on the Miscellaneous page |

|---|

| The following discussion has been closed. Please do not modify it. |

Hello. I just bought this motor-scooter from a private seller on Craigslist for $700. The model-year was 2006, and has almost 2700 miles. (The scooter allegedly cost $2400 brand-new.) I am allegedly the 4th owner now. After test-driving it for some time, I noticed that the braking power has weakened. I tried to send it to a Motorcycle Supply establishment in town, but the lead mechanic took a look and said that it’s an “oddball scooter,” like having bought a Russian car. He stated the difficulty to getting parts, and would rather not charge me the $60/hour just to find reliable parts sourcers online; he’d rather be paid to actually fix bikes. He took it on me to find the parts myself, and supply them to him once I have. The most critical parts I need are brake rotors and brake-lines (He said cables, IIRC.) This is because the brake-lines were “tightened to their limits.” (I didn’t ask, “So how does one loosen them again?” But I hope you can answer that as question #3.) He also mentioned something about a hydraulic going out for the front. Who knew that brakes were hydraulically-operated on the front, but cable-operated on the rear? (<-- #4) Now you see, my problem with finding parts suppliers, for this ‘’obscure’’ model, first off, would be by making sure they’re reputable, reliable and genuine. Google isn’t exactly all that great at telling how shady or legitimate these parts suppliers are. Therefore, 1. What can you tell me about your experiences with United Motors motor-scooters? 2. What parts suppliers would you find trustworthy who supply for United Motors motor-scooters, and how did they earn your trust in the first place? (Caveat: This should go without saying, but I must order from them online.) 3. (See remark about loosening “tightened” brakes.) 4. (See pointed-at remark.) I don’t care too much about cosmetic damage, as long as all important functions work right, and the Matrix 150 still gets me to my destinations on-time. Thanks kindly. --129.130.238.45 (talk) 16:39, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

|

Process, Protuberance, Condyle[edit]

Hello. In anatomy, what is the difference between a process, a protuberance, and a condyle? Thanks in advance. --Mayfare (talk) 16:42, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- A protuberance is anything that protrudes, i.e., sticks out -- it is not really a technical term. A process is an extension that attaches to something else or connects to something else. A condyle is specifically a protuberance on the end of a bone. Looie496 (talk) 16:58, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Is global warming necessarily bad for us?[edit]

I don't want to enter into the more basic questions like whether it's really happening or whether it's man made. I believe both to be true, although for me its existence is easier to prove than that man is at fault. Anyway, where is the evidence that it's necessarily a bad thing? And not neutral or positive at times? Or only marginally negative? OsmanRF34 (talk) 18:06, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Well, it depends on how you define "us". For some places, there will likely be positive benefits, as agriculture will improve, for example, or places become more "livable". However, since most of the world lives within a few scant feet of sea level, most of the world is likely to see serious disruption to their lives. A city like Venice is already essentially unlivable, except that nostalgia keeps people from abandoning it entirely. Look what an extra 12 feet of water did to New York City. And that was just a storm surge, not a permanent situation. Imagine just raising 12 feet of water permanently. There's also the idea that extra heat in general leads to more energy within the weather/climate systems, leading to more dramatic swings between highs and lows of all sorts. Global warming doesn't just lead to universally warmer temperatures and nothing else: many models indicate that global warming leads to more variation in climate: rather than relatively uniform temperatures and rainfall from year to year, we could find years of extreme heat followed by extreme cold, years of drought followed by years of floods, more extreme at both ends. That level of unpredictability is hard to deal with. There's also the idea that increasing temperatures generally will increase storm activity: storms form because of rising warm air off of warm oceans; warmer earth means warmer oceans means more storms on average. Again, however, that doesn't mean that every single square inch of the earth will end up worse off. Some places which are now desolate wastelands without any agricultural productivity could turn into major farming belts, for example. --Jayron32 18:23, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Also see The FAQ Q19. The speed of current climate change may seem slow to individual humans, but probably is unprecedented in nature. Ecosystems have problems adjusting at matching speed. Just imagine how long an oak forest needs to reach maturity, or how much smaller the ecosystem for marmots become if their preferred climate zone moves up a mountain. --Stephan Schulz (talk) 18:37, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Canada, for example, should benefit. In addition to vast areas becoming farmable, there's the opening up of the northwest passage for shipping. And most of their major cities aren't near sea level (Toronto, Quebec City, Ottawa). There are a few, though, like Vancouver and parts of Montreal. StuRat (talk) 18:41, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- There was a report that came out recently that many of the northern countries - US and northern Europe - would suffer little if any economic damage, but the warmer parts of the world would be very severely affected.

I'll see if I can run it down later.Wnt (talk) 19:04, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- There was a report that came out recently that many of the northern countries - US and northern Europe - would suffer little if any economic damage, but the warmer parts of the world would be very severely affected.

- I wouldn't include the US on that list. With major cities on the sea, like New York City, New Orleans, Miami, Pearl Harbor, Los Angeles, San Francisco, Seattle, Washington, DC, etc., and most of it subject to both hurricanes and tornadoes, it stands to lose quite a bit. Only Alaska will improve. StuRat (talk) 19:13, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Stu, your comment that Canada "should benefit" is way off base. Climate change is likely to increase the incidence of droughts, floods, heat waves, and forest fires in Canada. That is bad for agriculture, not good. The IPCC is the authoritative body for scientific implications of global warming, and covers several of these topics. In fact, Canada has already suffered increased economic damages due to global warming, via the mountain pine beetle In fact [14], there is evidence that this process is a positive feedback to global warming. SemanticMantis (talk) 23:58, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Unless global warming does at least 10,000 years worth of erosion to the Canadian shield and increases PPFD, warmer weather will not open up any land in Canada for agriculture. Also, the migration of typically southern pests north, and a faster maturation period for insect pests already here, will hurt Canadian agriculture. 50.101.137.171 (talk) 01:05, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- plus, you can't just take plants that evolved to grow in one latitude and grow them in a higher latitude, just because the temp is the same, since they tend to time their growth cycles, maturity, etc. by length of day (which is much less variable than temperature, and therefore less likely to trigger the plant into trying to go to seed in a warm May rather than the usual August, etc.). Onions, for instance, which come in long day and short day varieties. Anecdotal evidence: a friend of mine who attempted small-scale farming in northern Alberta, and claims to have grown vegetables which didn't have enough time to polymerize all the sugars into starch, cellulose, etc. and would break down into slush/dishwater at any attempt to cook them. Gzuckier (talk) 03:20, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- You should use crops which grow in warm places at the same latitude, then. Due to the Gulf Stream, Northern Europe is relatively warm, despite the northern latitude, so try those crops. StuRat (talk) 04:48, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- PPFD - photosynthetic photon flux density, or the related, Photosynthetically active radiation, here's a world map of PAR by month, [15] Even in July, light levels are too low in the northern half of Canada for plant agriculture. And yes, most of Canada's soil is not arable, class 7 land. [16] All the pink in that map will never be used for agriculture, and that's a map of Ontario. The last ice age scrapped away the soil, leaving only the rock underneath. 50.101.137.171 (talk) 16:31, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- One option would be to move soil there from once fertile lands to the south, which are now subject to drought. That soil map also seems to show that the soil is poor at mid-latitudes, but again improves at northern latitudes. (BTW, what were they thinking, using yellow to mean 3 different things, instead of using a different color for each ? Maybe they were originally different colors, but the pic was lowered to 16 colors when saved once.) I'd also like to see the soil quality map for the rest of Canada. StuRat (talk) 17:31, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Umm, Canada is a little bit on the large size, you might need to take about all the soil in Europe to cover up the Canadian shield and tundra. The colours really are that poorly chosen, I've read the original books. For other provinces, see [17]. 50.101.137.171 (talk) 20:43, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I wonder, since China has a building boom right now, are they being smart and avoiding building on the coast ? StuRat (talk) 19:15, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- oh dear, now i wish your question hadn't impelled me to search that out. "Nuclear construction set for coast by 2015" Gzuckier (talk) 03:26, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- And are they building it just like the Fukushima Daiichi Nuclear Power Plant ? StuRat (talk) 17:31, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I'm guessing they're built entirely out of Chinese drywall. Gzuckier (talk) 19:25, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Yes, there is evidence that global warming is "bad" (in terms of economic damages to human society, not to mention many other factors). For a brief overview, take a look at the latest IPCC report. SemanticMantis (talk) 00:07, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- There can also be sudden events that could cause our civilization to collapse. E.g. if due to droughts and floodings, agriculture fails for a few years in a row in China, India and Russia, then that will cause big problems, because the total food production then isn't sufficient to meet the demand. Countries will then have to close their markets to prevent everything from exported away to China, but then that would lead to the collapse of the World economy. If e.g. Saudi Arabia can't buy grain using their oil dollars, there is no point in selling any oil. Count Iblis (talk) 01:50, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- The main thing you may think is that: "I am living up in the hills, I won't be impacted by raising sea levels". But one thing you can be absolutely sure, is that the coast-living people will flood towards you, to seek refuge, and beleive me, millions and millions of refuges arriving in your area will seriously change you life. On top of this, you need to take into account that there will much less farmland available, which means food prices will raise automatically.--Lgriot (talk) 09:33, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I found that report I mentioned. Reading through this can be exasperating, but you can eventually get to a hundred pages about the methodology; it's not all colored circles and ideograms. The gist is that U.S. Russia, Europe, Australia, Argentina are OK, but Africa and Southeast Asia are screwed. Wnt (talk) 17:33, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Note that rapid global climate change is the real problem. If it happens slowly enough; plants, animals, and humans will be able to adapt. StuRat (talk) 17:55, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- So long as we don't go nearly as far as Venus or Mars temperature wise, or have a climate like some planets where 700km/h wind storms are common... 50.101.137.171 (talk) 20:43, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- What climate that is better or worse is of course subjective but our current civilisation have extremely big investments that are adopted to the current climate. Not only the physical structures eg. cities but also organizational capital in the organization of the society. If the fertile and best habitable areas in the world got shifted around over the continents the cost following the mass migration of billions of people and the conflicts it creates can be substantial. Gr8xoz (talk) 20:53, 10 November 2012 (UTC)

- I don't think what climate is best for people is subjective. You can look at which climates historically supported the largest populations of people, and conclude that those climates are best, if your goal is to keep humans alive. I'd say that subtropical and tropical climates are best, with arctic/antarctic climates only sparsely populated. StuRat (talk) 02:13, 13 November 2012 (UTC)

Perfect circles[edit]

This is a purely theoretical question, I understand perfect circles do not exist and probably never shall, but could someone answer this for me?

If perfect circles existed, as in Aristotle's wheel paradox, then a small circles circumference could be made to trace a ridiculous length by being attached to a larger circle. My question is this, would this make it possible to create infinite energy?

Different sized cogs turn at different rates due to the way their teeth are arranged. This is due to how many teeth fit on cogs relative to their size and the size of the cogs around them, right?

But if perfect circles existed, surely systems could be developed where cogs were replaced with completely circular pieces of metal or wood (as a circle could be described as a cog with an infinite amount of infinitesimal teeth), right? And if this was so different sized circular pieces, unlike cogs, could turn at the same rates regardless of their size. Going by set theory both would have an amount of points in their circumference and the teeth could be put into 1-1 correspondence.

Now, my question is this, given that all cogs/circles could turn at the same rate regardless, could a cog-based device be created that gave infinite energy? If so how? Equations would be greatly welcomed!

Note: If you disagree with the idea that the points on the cogs/circles would be able to be put into one-to-one correspondence, please just humor me and assume that all circles could turn at the same rate regardless to address the question!

(I have also posted this in the math desk as I was unsure if it was a math or physics question)

— Preceding unsigned comment added by 31.52.169.134 (talk) 19:24, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- A perfect circle is a mathematical abstraction. You can't build physical objects out of ideas. μηδείς (talk) 19:34, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

I realize this is not a real world question that is directly applicable to our surroundings but in a universe where all the laws of physics were exactly the same except perfect circles exist, would this be possible? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 109.157.115.249 (talk) 19:38, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Regardless if you use circles or cogs, and regardless of whether they are perfect circles, a cog system does not create any energy. The only thing it does is transfer energy from one cog to the other. By using differently sized cogs/circles it is theoretically possible to create an infinite amount of torque, or to make an infinitesimally small circle spin at 'infinite' speeds (disregarding relativity for convenience), but the amount of energy put into the system is what you can get out of it, minus the energy lost due to friction. - Lindert (talk) 19:42, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

The premise of the question is flawed, in any event. Even if the center circle were perfect and contained an infinite number of cogs, they are still slipping. I assume you got this idea from the last sentence of the article you linked, but the infiniteness of the points on either wheel is irrelevant to the fallacy. Someguy1221 (talk) 19:52, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

I actually got it from this book:

It contains a much more detailed description of the paradox and highlights the flaws in all current theories and explanations to the paradox. That page does not give as much detail as this. Does anyone have an equation for energy transfer between cogs? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 109.157.115.249 (talk) 20:01, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

This is one of Zeno's paradoxes that he didn't get around to. The idea is that a cog of any size, turning, goes through an infinite number of positions, so they all have potentially the same number of teeth. However, the limit of the number of teeth with finer and finer cogs is always according to their sizes, and this mathematical abstraction remains irrelevant. The comical way to put it is - the cogs have an infinite number of teeth, which each mesh with their counterparts at a different moment -- therefore it takes an infinite amount of time for them to complete a revolution... :) Wnt (talk) 20:33, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

Didn't Zeno show that an arrow can go through an infinite amount of positions in a finite amount of time though? Surely this concept could be replicated? If you have a small cog and spin it, the speed isn't effected by the number of teeth is it? — Preceding unsigned comment added by 109.157.115.249 (talk) 21:37, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Well, I was being somewhat humorous - the point of the paradox is that an infinite series can have a finite sum; that the duration of a moment can be infinitesimally small. Nonetheless, in relativity, space and time can be exchanged in different frames of reference. If infinity meant a one-to-one correspondence, then the infinite number of teeth in the cog would correspond to an equal infinite number of moments in the progression from past to future ... which are defined, I suppose, in terms of the period being considered. In other words, it's just absurd. Put it this way: infinity of any given type, multiplied by 5.2, equals what? Infinity. So the cogs have a truly undefined and undefinable gearing ratio when they have infinite numbers of teeth - there's no way to say how fast they turn or how fast relative to one another - it's all just a singularity in your equations. The way physics deals with that is to pick some other set of equations. Wnt (talk) 17:44, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- The OP has said he's not looking for a real world answer, so, here it is, a hat. μηδείς (talk) 23:30, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- The OP did not ask for either an opinion or a prediction about a future event, so your hat comment is, at best, misleading. It's completely legitimate to ask about an ideal universe, because every single scientific law ever invented is only true in an ideal universe. Newton's laws, for example, are only approximations that aren't even good enough for everyday purposes (like GPS); do you plan on hatting every question that asks about Newton's laws, on the grounds that they don't apply to the real world?

- First, I want to point out that ideal circles can exist in a Newtonian, special relativistic, or general relativistic world, but in the first 2 cases, conservation of energy is a result of something much more fundamental than different-sized circles: Noether's theorem. If any physical laws are symmetric with respect to time, then no matter what the laws actually are, conservation of energy holds. Energy is not conserved in general relativity, but an excellent approximation of it holds on small scales. Only when you get to cosmological scales where the Hubble expansion dominates is the conservation of energy obviously violated.

- Second, I don't know whether the points could be put into 1-to-1 correspondence, but that is completely irrelevant. A transfer of energy is accomplished by work, and work is force applied over a finite distance. Right away that should tell you that you can't analyze points; you should be starting out by analyzing some finite distance, then take the limit as the distance goes to 0. --140.180.252.244 (talk) 05:04, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Um no, scientific law are true in this world, as well as an ideal world. Newton's laws don't work for GPS as he didn't know about relativity (ie they are wrong for fast moving objects and high gravitational fields). Einstein corrected this error by coming up with general relativity which does allow GPS to work in this universe (which is not an ideal one). But Newton's laws do work at low speed and low gravitational fields (in this world as well as an ideal one). Thermodynamics work in this universe ( which is not an ideal universe). Laws of science work here, if they don't work here then they are wrong, or we don't have a full picture. Otherwise we wouldn't be able to predict anything. Dja1979 (talk) 15:20, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- This looks like it's related to the somewhat elastic size of countable infinity, in that there are an infinite number of points in the circumference of both circles, and you can make a 1:1 correspondence between them, but that doesn't mean they get to the end (i.e. one full rotation) at the same time, since you never reach the end of your count. Kind of like Hilbert's paradox of the Grand Hotel. Just off the top of my head. Gzuckier (talk) 19:22, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Could dark matter be individual quarks?[edit]

To my knowledge most matter consists of arrangements of 3 quarks . The quarks are held together by the color force and have not yet been detected individually as the color force is so strong.

Dark matter particles do not interact with us except through gravitation so could dark matter simply be individual quarks that are not bound together via the color force?

The individual quarks could perhaps have been formed along with hydrogen in the early universe.

31.51.239.254 (talk) 20:16, 8 November 2012 (UTC) ap

- Quarks have more than color force: they also all have electromagnetic charge, so unbound quarks would still interact with other matter even if they could be found in an unbound state. --Jayron32 20:23, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Isn't by definition a quark s a fermion that interacts via the colour force. A fermion that doesn't interact via the colour force is called a lepton. Dja1979 (talk) 20:35, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- Only neutron and proton consist of quarks, not electron. Quarks make only nucleus, not the entire atom. So, arrangement of 3 quarks don't make most of the matter since electron is also a part of matter. Sunny Singh (DAV) (talk) 07:02, 12 November 2012 (UTC)

- According to most mainstream models of quantum mechanics, quarks simply cannot exist individually -- so far, all attempts to find individual quarks have failed, and all attempts to create them artificially have only resulted in the creation of additional quark-antiquark pairs given off as mesons. 24.23.196.85 (talk) 23:06, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- At my local particle accelerator, they often invite expert scientists to give public lectures about dark matter. Here's the last one I attended, Deep Science: Mining for Dark Matter (full video available online - you might enjoy watching it). I recall walking away that evening somewhat with the dismal impression that most dark matter is just very low density, low temperature hydrogen whose blackbody temperature peak wavelength is very long and whose radiated intensity is very low. In other words, it's large quantities of boring, cold, non-interacting gas. It sounds a lot more boring when phrased that way! We can speculate ad infinitum about properties of matter we can't see, and speculate how it might interact with things it will never encounter; but at some point such speculation ceases to be scientific. Anyway, at least a distinction should be made between "dark matter" in the general sense, and rare exotic weakly-interacting particles (such as the WIMP, in all of the many speculative and potentially non-baryonic forms that it takes). One of the hard parts about observational cosmology is that you can't see things that are dark - so you've got to draw scientific conclusions from very rigorous theoretical study, and a lot of careful consideration of the null hypothesis. Nimur (talk) 23:41, 8 November 2012 (UTC)

- The CMB shows that it isn't "large quantities of boring, cold, non-interacting gas" it is something else. Other evedence is bullet cluster which show that the centre of mass is differnt to the centre of light (hydrogen gas) of two super clusters of galaxies that have travelled through each other. This means the majority of the mass is made of something that very weakly or doesn't at all interact (except through gravity) with itself or other particles. The only discovered particle that fits this discription is the neutrino but the CMB data tells us that the ordinary (3 types of) neutrino is not the answer so must be something else not discovered yet. Dja1979 (talk) 01:12, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I beg to differ. The cosmic microwave background doesn't show anything. The bullet cluster doesn't show anything. Cosmologists look at these things. The CMB is just an observed effect we see when we look into space, and as it is not alive, it is unable to perform scientific demonstrations for us. Scientists draw conclusions by observing the CMB, and other observable effects. You can agree with whichever scientific conclusion you believe rests most solidly on the observational evidence; but I consider it invalid to state that the evidence itself shows anything. Many scientists believe that these observations support theories of exotic matter. I am not convinced. Nimur (talk) 15:42, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- The bullet cluster does show something. The majority of the mass is in a place that is different from the majority of the stars. This can be explained by the majority of the mass being an unknown particle that doesn't interact with anything much, so passing through relativly unimpeded, and the gas and dust of the galaxies that passed through each other causing drag so seperating from the mass. How does mostly hydrogen do this? The CMB agains shows something, okay you can't interact with it but it holds information which a theory has to explain. If you don't have dark matter then the data doesn't fit the theory of the big bang with only ordanry matter. So if you don't believe that dark matter causes the difference, then you have to come up with another way of explaning the data (the oscillations in the power spectrum of the CMB). Dja1979 (talk) 17:41, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- You place a higher degree of confidence in the evidence of gravitational lensing than I do. And you are not alone: a very large number of very prominent scientists agree with you - including the lecturer I linked above. In fact, NASA even published the phrase "direct proof" of dark matter in one of their Bullet Cluster press-release, attributed to a researcher affiliated with the Chandra program. However strong these words are, and despite my immense respect for many of these researchers, I am still not convinced. Nimur (talk) 20:21, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- When someone disagrees with the overwhelming consensus of the experts in the field, and said person is not an expert himself, it's his responsibility to demonstrate why the experts are wrong. It's not the experts' responsibility to disprove his theories. Otherwise, science can't progress, because there's always someone who will invent theories with no support and say "prove me wrong". --140.180.252.244 (talk) 22:38, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Hi Nimur, I place confidence in the gravitational lensing, as this is predicted by General Relativity (GR), so to say that gravitational lensing is wrong, is to say that GR is wrong. As all Earth based tests have shown GR to be right (and assumeing that the laws of physics are the same throughout the universe). So it's not just a case of I don't believe one set of data you have to say why it's wrong and then come up with a theory that will produce all the observed effects of the said thing you have said is wrong (need to rewrite GR so the GPS system etc still works), not just one (gravitational lensing). Dja1979 (talk) 23:20, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- You misunderstood me. Of course I believe that gravitational lensing can and does occur. I've studied physics for a long time, and have a high degree of confidence in most of the modern formulations of relativity. Perhaps I should have been more clear. I am skeptical that we are able to use specific observations of remote objects, and to make inferences about mass distributions of unknown objects, guided entirely by statistical models about distribution of other extragalactic objects. I am skeptical because I have studied imaging and numerical inversion for some time, and do not believe that the problems posed by gravitational lensing are well-formed, in the strict mathematical sense. Whether I am an expert in this subject is moot; and whether I can prove or substantiate my opinions is moot; Wikipedia is the wrong forum for me to put forth original research; and I have already provided links to content from recognized experts in the field. All I hope to do here is provide resources for enthusiasts who find the topic as exciting as I do. Perhaps when I get home I can dig up a few of my workbooks on gravitational lensing; I seem to recall taking an entire project-course where we simulated these effects in MATLAB. The interested reader might want to experiment for themselves: in fact, Chandra observational data are available free of charge to the public. In fact, here is the Bullet Cluster from the UKST Schmidt and its metadata, and here in X-ray, from Chandra. Perhaps you would like to invert for the mass distribution that obviously follows from this set of observations, and get back to me on my talk-page? You need not even waste any time implementing the hard parts of the code, like the data-management or the image-processing; all that is open-source and free software provided by the program office. All you have to do is implement the physics. Nimur (talk) 02:48, 10 November 2012 (UTC)

- You place a higher degree of confidence in the evidence of gravitational lensing than I do. And you are not alone: a very large number of very prominent scientists agree with you - including the lecturer I linked above. In fact, NASA even published the phrase "direct proof" of dark matter in one of their Bullet Cluster press-release, attributed to a researcher affiliated with the Chandra program. However strong these words are, and despite my immense respect for many of these researchers, I am still not convinced. Nimur (talk) 20:21, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- The bullet cluster does show something. The majority of the mass is in a place that is different from the majority of the stars. This can be explained by the majority of the mass being an unknown particle that doesn't interact with anything much, so passing through relativly unimpeded, and the gas and dust of the galaxies that passed through each other causing drag so seperating from the mass. How does mostly hydrogen do this? The CMB agains shows something, okay you can't interact with it but it holds information which a theory has to explain. If you don't have dark matter then the data doesn't fit the theory of the big bang with only ordanry matter. So if you don't believe that dark matter causes the difference, then you have to come up with another way of explaning the data (the oscillations in the power spectrum of the CMB). Dja1979 (talk) 17:41, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I beg to differ. The cosmic microwave background doesn't show anything. The bullet cluster doesn't show anything. Cosmologists look at these things. The CMB is just an observed effect we see when we look into space, and as it is not alive, it is unable to perform scientific demonstrations for us. Scientists draw conclusions by observing the CMB, and other observable effects. You can agree with whichever scientific conclusion you believe rests most solidly on the observational evidence; but I consider it invalid to state that the evidence itself shows anything. Many scientists believe that these observations support theories of exotic matter. I am not convinced. Nimur (talk) 15:42, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- Nimur, please don't speculate about things you know nothing about. It's absolutely not true that any substantial portion of dark matter could be hydrogen gas. In fact, there's very little doubt that dark matter is made up of WIMPs--weakly interacting massive particles. I'll try to summarize the evidence, but basically Dja1979 hit the main points.

- A spectral analysis of the cosmic microwave background gives numerous peaks. The second peak is determined by the baryon-photon ratio; all ordinary matter, including hydrogen, is made up of baryons. The photon density of the universe can be accurately calculated because most of the universe's photons are from the CMB, and the CMB is modelled very well by a blackbody. From these data, the baryon density of the universe can be calculated, and it turns out to be about 4% of the universe's total energy density. We know from independent measurements that matter accounts for 27%, so almost 90% of the universe's matter cannot be baryonic, and certainly can't be hydrogen.

- Anisotropies in the CMB were predicted to be on the order of 1e-3. It turns out that in actuality, they were on the order of 1e-5. If only normal matter existed, the CMB anisotropies would not have been large enough to form the structure we see today. There must have been a large number of particles that decoupled from the photon-matter fluid long before baryonic matter, and provided the seeds for the large-scale structures seen today. The very fact that they decoupled before baryonic matter means they're weakly interacting.

- Dark matter distributions have been mapped out using various techniques, including gravitational lensing, the virial theorem, and measurements of galaxy rotation curves. Dark matter is observed to lie in spherical halos around galaxies, and the Bullet Cluster shows that these dark matter halos have a behavior distinct from the rest of the galaxy (i.e. they don't interact as much). Hydrogen doesn't form spherical halos like this; it tends to coalesce, heat up dramatically, and form star clusters at the slightest perturbation. The fact that spherical halos exist mean that the particles in them must be weakly interacting--both with photons and with themselves--and massive, because if they had low mass, they would be moving too quickly to coalesce into halos.

- Don't imagine that astronomers can't observe dark, cold hydrogen gas if it filled the universe. Even if it doesn't emit light, absorption lines would be painfully obvious at every redshift, in the spectrum of every extragalactic object. As it turns out, astronomers do observe numerous Lyman alpha forests in extragalactic spectra, but they're not at all close to the amount needed to explain dark matter.

- The only N-body simulations that reasonably simulate the structure we see today, starting from the initial conditions imposed by the CMB, assume a large amount of cold (aka massive), weakly interacting matter. --140.180.252.244 (talk) 06:04, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- While you're making these good replies - my understanding is that supersymmetry took some hits lately. But is the old fashioned mirror matter still in contention? Could there actually be planets and stars that work like our own, but are invisible and non-interacting to us, except by some very weak coupling of mirror photons with us? Wnt (talk) 09:47, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I think most people expect dark matter to be the neutralino as this is the lightest supersymetric particle in most supersymetric models. As you say certain model of supersymmetry have been disproven but there's alway a version to take it's place we have a long way to go before we disprove all of supersymmetry. As for mirror matter it seems unlikely. I refere back to the bullet cluster example. There most of the mass of the galaxies didn't interact with each other when they passed through each other. If dark matter was like ordinary matter with dark light dark quarks etc then they would of interacted with each other so producing drag. So it seems that what ever dark matter is, it interacts with itself as much as it does ordonary matter. Dja1979 (talk) 15:05, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I find it alarming that I have, thus far, provided the only external reference to a web-resource on the cosmology of dark matter - a video presentation at the facility where the quark was discovered, presented by an expert cosmologist, available free on the internet. If we have any more highly-trained, world-renowned expert cosmologist contributors who know more about this subject - or even if there are any well-informed non-expert enthusiasts present - why don't you provide some links to texts, papers, books, videos, or web-resources? I'd love to inform myself more on the topic. In the spirit of full disclosure, I am not currently a professionally-employed-cosmologist, but I think it's a little unfair to say I know nothing of the subject. Nimur (talk) 15:48, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I should clarify that when I said "you're making good replies" above, I was speaking plural, including you, Nimur, who are absolutely of the very best contributors on this Refdesk overall. But I also appreciate a good fight over these ideas to make clearer where the action is. :) Wnt (talk) 17:06, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I watched that video. Not only does Golwala not say dark matter can be hydrogen, he says exactly the opposite. In fact, he recounts almost every point I've made for why it cannot be hydrogen. I'll paraphrase a few quotes, because they're too long to copy exactly:

- 14:00: "The red here shows X-ray emission from normal matter. You see that the normal matter is not lined up with total matter, which itself is interesting.

- 15:30: "You've got 1 component that collides...it interacts like normal matter does...but then you've got a large chunk that doesn't interact."

- 16:15: "You need something that's not the normal matter we know about to explain how this thing is behaving."

- 16:30: "Can it be normal matter? Well, for one thing the dark matter has to be collisionless, and you can't have that with normal matter. There are cosmological measurements that strongly indicate normal matter is only 1/6 the total amount of matter..there's the abundances of light elements, we understand very well how they were produced, and can use the measured abundances to determine how much normal matter there is in the universe. And it says normal matter only contains 1/6 the total mass we measure in numerous ways. There's also the CMB...fluctuations are seeds of all the structures we see today...the fluctuations are actually too large for them to be caused by normal matter, because at the time, normal matter couldn't collapse. In some sense, the fluctuations were also too small...they're a factor of 10 too small to cause the structures we see today."

- 19:00: "Let's hypothesize a new particle."

- 21:00: possible explanations with modified gravity

- 22:50: "Modified gravity doesn't seem to fit the data as well as dark matter"

- 24:20: "This particle must interact with gravity and the weak force, and no others, because if it did, we would have already seen it."

- 25:25: "They have to have a mass of about 100 proton masses, give or take a factor of 10, and have to move at about the same speed as other stuff in our galaxy."

- The rest of the video talks about various experiments to detect WIMPs. To answer Wnt, the mirror particle idea seems unlikely for exactly the reason Dja1979 gave: dark matter particles have to interact weakly with themselves, not just with normal matter. Specific candidates for dark matter are much more speculative than the fact that dark matter exists, and that it cannot be baryonic. Don't confuse the claim "dark matter is something we've never seen before" with "dark matter is particle X, where X=neutralino (or whatever else)" If somebody with green skin and 3 arms started robbing you, you can be very certain that you've never seen this person before, but identifying the person is much harder. --140.180.252.244 (talk) 17:57, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I find it alarming that I have, thus far, provided the only external reference to a web-resource on the cosmology of dark matter - a video presentation at the facility where the quark was discovered, presented by an expert cosmologist, available free on the internet. If we have any more highly-trained, world-renowned expert cosmologist contributors who know more about this subject - or even if there are any well-informed non-expert enthusiasts present - why don't you provide some links to texts, papers, books, videos, or web-resources? I'd love to inform myself more on the topic. In the spirit of full disclosure, I am not currently a professionally-employed-cosmologist, but I think it's a little unfair to say I know nothing of the subject. Nimur (talk) 15:48, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- I think most people expect dark matter to be the neutralino as this is the lightest supersymetric particle in most supersymetric models. As you say certain model of supersymmetry have been disproven but there's alway a version to take it's place we have a long way to go before we disprove all of supersymmetry. As for mirror matter it seems unlikely. I refere back to the bullet cluster example. There most of the mass of the galaxies didn't interact with each other when they passed through each other. If dark matter was like ordinary matter with dark light dark quarks etc then they would of interacted with each other so producing drag. So it seems that what ever dark matter is, it interacts with itself as much as it does ordonary matter. Dja1979 (talk) 15:05, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- While you're making these good replies - my understanding is that supersymmetry took some hits lately. But is the old fashioned mirror matter still in contention? Could there actually be planets and stars that work like our own, but are invisible and non-interacting to us, except by some very weak coupling of mirror photons with us? Wnt (talk) 09:47, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- The CMB shows that it isn't "large quantities of boring, cold, non-interacting gas" it is something else. Other evedence is bullet cluster which show that the centre of mass is differnt to the centre of light (hydrogen gas) of two super clusters of galaxies that have travelled through each other. This means the majority of the mass is made of something that very weakly or doesn't at all interact (except through gravity) with itself or other particles. The only discovered particle that fits this discription is the neutrino but the CMB data tells us that the ordinary (3 types of) neutrino is not the answer so must be something else not discovered yet. Dja1979 (talk) 01:12, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

- This article suggests WIMPs may or may not have been detected. http://www.insidescience.org/content/possible-dark-matter-signal-spotted/836. μηδείς (talk) 16:22, 9 November 2012 (UTC)

Mirror matter could be part of the dark matter. It is possible that dark matter isn't all neutralinos, axions, sterile neutrinos etc. but a combination of all of these candidates. The constraint from the Bullet cluster does leave room for some mirror matter models, because it implies a constraint on the cross section that depends on the density which is easy to evade. Count Iblis (talk) 17:05, 9 November 2012 (UTC)