Wedding of Princess Margaret and Antony Armstrong-Jones

Princess Margaret and Antony Armstrong-Jones on their wedding day. | |

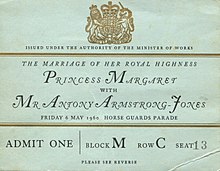

| Date | 6 May 1960 |

|---|---|

| Venue | Westminster Abbey |

| Location | London, England, United Kingdom |

| Participants | Princess Margaret Antony Armstong-Jones |

The wedding of Princess Margaret and Antony Armstrong-Jones took place on Friday, 6 May 1960 at Westminster Abbey in London.[1] Princess Margaret was the younger sister of Queen Elizabeth II, while Antony Armstrong-Jones was a noted society photographer.

Engagement

[edit]Princess Margaret met photographer Antony Armstrong-Jones in 1958 at a dinner party at the Chelsea home of Lady Elizabeth Cavendish.[2][3] The two had previously encountered each other when Armstrong-Jones was the photographer at the wedding of Margaret's friends, Lady Anne Coke and The Hon. Colin Tennant, in April 1956.[4] In October 1959, Armstrong-Jones was invited to stay at Balmoral Castle. The public assumed he was there to photograph the royal family. They became engaged shortly after[5] and on 26 February 1960, Clarence House announced the engagement.[6] Armstrong-Jones presented the Princess with an engagement ring set with a ruby surrounded by a marguerite of diamonds.[7][8] He had designed the ring himself after a rose in honour of Margaret's middle name.

Two days before the wedding, on 4 May, there was a white-tie ball at Buckingham Palace attended by the Prime Minister and the Archbishop of Canterbury.[citation needed]

Wedding

[edit]

Ceremony

[edit]Margaret made her way with the Duke of Edinburgh from Clarence House in the Glass Coach, arriving at the church at 11:30.[3] The wedding took place at Westminster Abbey and was conducted by The Most Rev. Dr Geoffery Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury and The Very Rev. Eric Abbott, Dean of Westminster.[3] It was the first royal wedding to be broadcast on television and had an estimated 300 million viewers, 20 million of which from the UK.[9][10] Richard Dimbleby, Jean Metcalfe, Anne Edwards, Brian Johnston, and Wynford Vaughan-Thomas covered the event for the BBC.[9]

Attendants

[edit]Armstrong-Jones's best man was Dr Roger Gilliatt, son of the Queen's gynecologist.[3] The Countess of Rosse, the groom's mother, had hoped he would choose his half-brother, Lord Oxmantown, as his best man. However, resentment of their mother's favouritism led him to reject this suggestion. On 19 March, it was announced he had chosen Jeremy Fry for the role, but Fry was convicted of "importuning for immoral purposes" after allegedly approaching a man for sex, so was replaced.[11][12]

Princess Margaret was attended by eight bridesmaids:[13]

- The Princess Anne, daughter of The Queen and The Duke of Edinburgh

- Miss Angela Nevill, daughter of Lord Rupert Nevill and Lady Rupert Nevill

- Lady Rose Nevill, daughter of The Marquess and Marchioness of Abergavenny

- The Hon. Catherine Vesey, daughter of The Viscount and Viscountess de Vesci

- Miss Sarah Lowther, daughter of Mr and Mrs John Lowther

- Lady Virginia Fitzroy, daughter of Earl and Countess of Euston

- Miss Annabel Rhodes, daughter of The Hon. Margaret and Mr Denys Rhodes

- Miss Marilyn Wills, daughter of The Hon. Jean and Captain John Wills.

Music

[edit]Prior to the service, works by Johann Sebastian Bach, George Frideric Handel, Henry Purcell and William Henry Harris were played on the organ. The bride walked down the aisle to the hymn "Christ is Made the Sure Foundation" to the tune Westminster Abbey by Purcell. Throughout the service, anthems by Franz Schubert, William Byrd and Gustav Holst were sung. The recessional music, at the special request of the bride, was "Trumpet Tune and Airs" by Purcell.[14]

Attire

[edit]The Princess wore a silk organza gown designed by Norman Hartnell. She accessorized with the Poltimore tiara, which she had purchased at auction a year earlier, and a diamond riviére of 34 old-cut diamonds given to the bride by her grandmother, Queen Mary.[15] She carried a bouquet of white orchids. Hartnell also designed the outfits of The Queen and The Queen Mother.

Armstrong-Jones and all male members of the royal family, except for Lord Mountbatten, wore morning dress.

Guests

[edit]Notable guests in attendance included:

Relatives of the bride

[edit]- Queen Elizabeth The Queen Mother, the bride's mother

- The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, the bride's sister and brother-in-law

- The Prince of Wales, the bride's nephew

- The Princess Anne, the bride's niece (bridesmaid)

- The Queen and the Duke of Edinburgh, the bride's sister and brother-in-law

- The Princess Royal, the bride's paternal aunt

- The Earl and Countess of Harewood, the bride's first cousin and his wife

- The Hon. Gerald and Angela Lascelles, the bride's first cousin and his wife

- The Duke and Duchess of Gloucester, the bride's paternal uncle and aunt

- Prince William of Gloucester, the bride's first cousin

- Prince Richard of Gloucester, the bride's first cousin

- The Duchess of Kent, the bride's paternal aunt by marriage

- The Duke of Kent, the bride's first cousin

- Princess Alexandra of Kent, the bride's first cousin

- Prince Michael of Kent, the bride's first cousin

- Lady Patricia and Admiral The Hon. Sir Alexander Ramsay, the bride's first cousin twice removed, and her husband

- Captain Alexander Ramsay of Mar and the Mistress of Saltoun, the bride's second cousin once removed, and his wife

- Princess Alice, Countess of Athlone, the bride's first cousin, twice removed and paternal great aunt by marriage

Other descendants of Queen Victoria

[edit]- The Queen of Denmark, the bride's second cousin once removed (and godmother)

- The Earl Mountbatten of Burma, the bride's second cousin once removed

- The Lady Brabourne, the bride's third cousin

- The Hereditary Prince of Baden, the bride's third cousin

- Prince Ludwig of Baden, the bride's third cousin

- Prince Karl of Hesse, the bride's third cousin

- The Hon. Jean and Captain John Wills, the bride's first cousin and her husband

- Marilyn Wills, the bride's first cousin, once removed

- The Hon. Margaret and Denys Rhodes, the bride's first cousin and her husband

- Annabel Rhodes, the bride's first cousin, once removed

Relatives of the groom

[edit]- Major and Mrs Ronald Armstrong-Jones, the groom's father and stepmother

- The Viscountess and Viscount de Vesci, the groom's sister and brother-in-law

- The Hon. Catherine Vesey, the bridegroom's niece

- The Viscountess and Viscount de Vesci, the groom's sister and brother-in-law

- The Countess and Earl of Rosse, the groom's mother and stepfather

- Lord Oxmantown, the groom's half-brother

- The Hon. Martin Parsons, the groom's half-brother

Politicians

[edit]British politicians

[edit]- The Rt Hon. Harold Macmillan, Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, and Lady Dorothy Macmillan

- The Rt Hon. Selwyn Lloyd, Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs

- The Rt Hon. Sir Winston Churchill, former Prime Minister of the United Kingdom

Commonwealth politicians

[edit]- The Rt Hon. Robert Menzies, Prime Minister of Australia

- The Rt Hon. John Diefenbaker, Prime Minister of Canada

- The Rt Hon. Kwame Nkrumah, Prime Minister of Ghana

- The Hon. Jawaharlal Nehru, Prime Minister of India

- Field Marshal Muhammad Ayub Khan, President of Pakistan

- The Rt Hon. Walter Nash, Prime Minister of New Zealand[16]

The wedding coincided with the 10th Commonwealth Prime Ministers' Conference held at Windsor Castle. As a result, many of the Commonwealth dignitaries attended the wedding.[17]

Religious figures

[edit]- The Most Rev. Dr Geoffrey Fisher, Archbishop of Canterbury

- The Very Rev. Eric Abbott, Dean of Westminster

Other notable guests

[edit]- Dr Roger Gilliatt and Penelope Gilliatt (best man)

- Earl and Countess of Euston

- Lady Virginia FitzRoy (bridesmaid)

- Mr and Mrs John Lowther

- Sarah Lowther (bridesmaid)

- The Marquess and Marchioness of Abergavenny

- Lady Rose Nevill (bridesmaid)

- Lord and Lady Rupert Nevill

- Angela Nevill (bridesmaid)

- The Hon. Iris Peake

Aftermath

[edit]Following a balcony appearance and a wedding breakfast for 150 guests at Buckingham Palace, the bride changed into her Victor Stiebel going-away outfit and they departed in an open Rolls-Royce. They spent their six-week honeymoon touring the Caribbean on HMY Britannia.[18] On 26 May, while away on honeymoon, Camilla Fry, wife of Jeremy Fry, gave birth to Armstrong-Jones's illegitimate daughter, Polly. Allegations of this were first raised in 2004 and confirmed when Armstrong-Jones agreed to take a paternity test.[19]

On 6 October 1961, Armstrong-Jones was raised to the peerage as Earl of Snowdon and Viscount Linley, of Nymans in the County of Sussex, by Queen Elizabeth II. He became "The Right Honourable The Earl of Snowdon" and Princess Margaret became "Her Royal Highness The Princess Margaret, Countess of Snowdon." The couple had two children, David (born 1961), now the 2nd Earl of Snowdon, and Sarah (born 1964).

The Snowdons separated in 1976, subsequently divorcing on 11 July 1978. It was the first divorce by a senior member of the royal family since that of Princess Victoria Melita of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha and Ernest Louis, Grand Duke of Hesse in 1901. On 15 December 1978, Snowdon remarried Lucy Lindsay-Hogg, separating in 2000. They had a daughter, Frances (b. 1979). On 30 April 1998, Snowdon fathered another illegitimate child, Jasper William Oliver Cable-Alexander.[20]

After years of ill health, Princess Margaret, who never remarried, died on 9 February 2002, aged 71. Lord Snowdon died on 13 January 2017, aged 86.

References

[edit]- Notes

- ^ "Princess Margaret, daughter of King George IV" (PDF). Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ "Lady Elizabeth Cavendish obituary". thetimes.co.uk. The Times. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ a b c d "1960: Margaret weds Armstrong-Jones". BBC. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Glenconner, Anne (17 October 2019). Lady in Waiting: My Extraordinary Life in the Shadow of the Crown. Hodder & Stoughton. ISBN 978-1529359060.

- ^ "Princess Margaret's wedding". BBC. Retrieved 14 May 2018.

- ^ Frost, Katie (6 November 2019). "The True Story of Princess Margaret and Antony Armstrong-Jones's Love Affair". Town & Country. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "A Close Look at the British Royal Family's Engagement Rings (slide 4)". Vogue. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ Bonner, Mehera (25 October 2017). "The Most Gorgeous Royal Engagement Rings: Your Official Guide to Who Owns What". Marie Claire UK. Retrieved 15 May 2018.

- ^ a b "The Wedding of Princess Margaret televised". BBC. Retrieved 14 August 2022.

- ^ Best, Chloe. "How Princess Margaret made royal history at her wedding with Antony Armstrong-Jones". Hello!. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Alderson, Andrew (31 May 2008). "Lord Snowdon, his women and his love child". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ de Courcy, Anne (9 January 2009). "Excerpt: The Princess and the Photographer". Vanity Fair. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ "'The Royal Wedding 6 May 1960'". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 19 September 2021.

- ^ "Princess Margaret, daughter of King George IV" (PDF). Westminster Abbey. Retrieved 14 March 2019.

- ^ "QUEEN MARY'S DIAMOND RIVIERE". Christie's. Retrieved 11 May 2020.

- ^ "Mr. Nash to Attend". The Press. Vol. XCIX, no. 29151. 11 March 1960. p. 2.

- ^ "May Wedding Roll 2 (1960)". British Pathé. YouTube. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Heald, pp. 119–121; Warwick, pp. 229–230

- ^ Hallemann, Caroline (8 December 2017). "Did Antony Armstrong-Jones Really Have an Illegitimate Child?". Town & Country. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- ^ Bearn, Emily (16 April 2003). "Still playing Peter Pan". The Telegraph. Retrieved 12 May 2020.

- Sources

- Heald, Tim (2007), Princess Margaret: A Life Unravelled, London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, ISBN 978-0-297-84820-2

- Warwick, Christopher (2002), Princess Margaret: A Life of Contrasts, London: Carlton Publishing Group, ISBN 0-233-05106-6