User:Nanobear~enwiki/Fobos-Grunt

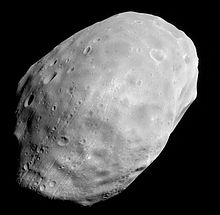

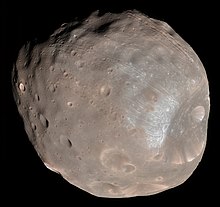

Fobos-Grunt (Russian: Фобос-Грунт, lit. «Phobos-Soil») is a sample return mission to Phobos, one of the moons of Mars, with the main purpose of investigating the structure and origin of the moon. Financed by the Russian space agency Roscosmos and developed by NPO Lavochkin and Russian Space Research Institute, Fobos-Grunt is to become the first Russian interplanetary mission since the failed Mars 96. It is also set to become the first spacecraft to return a macroscopic extraterrestrial sample from a planetary body since Luna 24 in 1976[1] Launch is scheduled for 8 November 2011 from Baikonur Cosmodrome. The spacecraft is expected to reach Mars' orbit in September 2011, with landing on Phobos scheduled for February 2013. The return rocket, containing a Phobos soil sample of up to 200 g in mass, is expected to be back on Earth in August 2014.

The Chinese Mars orbiter Yinghuo-1 will be sent together with the mission, as will the Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment funded by the Planetary Society.

Project history[edit]

Development[edit]

The Fobos-Grunt project began in 1999, when the Russian Space Research Institute and NPO Lavochkin, the main developer of Soviet and Russian interplanetary probes, initiated the study of feasibility of a Fobos sample-return mission. An initial RUB 9 million was invested into the project at this time. The initial spacecraft design was to be similar to the probes of the Phobos program launched in the late 1980s.[2] Development of the spacecraft started in 2001 and the preliminary design was completed in 2004.[3] For years, the project stalled due to low levels of financing of the Russian space program. This changed in the summer of 2005, when the new government plan for space activities in 2006–2015 was published. Fobos-Grunt was now made one of the program's flagship missions. With substantially improved funding, the launch date was set for October 2009. The 2004 design was revised a couple of times and international partners were invited to join the project.[2] In June 2006, NPO Lavochkin announced that it began manufacturing and testing the development version of the spacecraft's onboard equipment.[4]

On 26 March 2007, Russia and China signed a cooperative agreement on the joint exploration of Mars, which included sending China's first interplanetary probe Yinghuo-1 to Mars together with the Fobos-Grunt spacecraft.[5]

2009 launch date[edit]

The October 2009 could not be achieved due to delays in the spacecraft development. During 2009, officials admitted that the schedule was very tight, but still hoped until the last moment that a launch could be made.[6] On September 21 the mission was officially announced to be delayed until the next launch window in 2011.[7][8][9][10] The main reason for the delay was difficulties encountered during development of the spacecraft's onboard computers. While the Moscow-based company Tehkhom provided the computer hardware on time, the internal NPO Lavochkin team responsible for integration and software development fell behind schedule.[11] The retirement of NPO Lavochkin's head Valeriy N. Poletskiy in January 2010 was widely seen as linked to the delay of Fobos-Grunt. Viktor Khartov was appointed the new head of the company.[12]

Launch preparations[edit]

The spacecraft arrived at Baikonur on October 17, 2011 and was transported to Site 31 for pre-launch processing.[13] The launch is scheduled for November 8, 2011 using Zenit-2 launch vehicle.[14] In case of a delay, the possible launch window extends up to around 25 November.[1]

Two firings of the main propulsion unit in Earth orbit are required to send the spacecraft onto the interplanetary trajectory. Since both firings will take place outside the range of Russian ground stations, the project participants have asked volunteers around the world to take optical observations of the burns, e.g. with telescopes.[15]

Post-launch[edit]

Following launch, the spacecraft will insert itself into a hyperbolic geocentric escape trajectory using its own autonomous main propulsion unit (MDU) which is derived from the Fregat upper stage.[16][17] End of October the launch date was issued for the November 9, 2011 00:26 a.m.[18] The propulsion module constitutes the cruise-stage bus of Fobos-Grunt. Mars orbit arrival is expected during the fall 2012.

The return vehicle is scheduled to reach Earth in August 2014.[19][20]

Purpose[edit]

Fobos-Grunt is an interplanetary probe that includes a lander to study Phobos and a sample return vehicle to return a soil sample (about 200 g)[14] to Earth. It will also study Mars from orbit, including its atmosphere and dust storms, plasma and radiation.

Science goals[edit]

- Delivery of samples of Phobos soil to Earth for scientific research of Phobos, Mars and Martian vicinity;

- In situ and remote studies of Phobos (to include analysis of soil samples);

- Monitoring the atmospheric behavior of Mars, including the dynamics of dust storms;

- Studies of the vicinity of Mars, including its radiation environment, plasma and dust;[19]

- Study of the origin of the Martian satellites and their relation to Mars;

- Study of the role played by asteroid impacts in the formation of terrestrial planets;

- Search for possible past or present life (biosignatures);[21]

- Study the impact of a three year interplanetary round-trip journey to extremophile microorganisms in a small sealed capsule (LIFE experiment).[22]

Mission description[edit]

Journey[edit]

The spacecraft's journey to Mars is scheduled to take about ten months. After arriving in Mars orbit, the main propulsion unit (MDU) and the transfer truss will separate and the Chinese Mars-orbiter will be released. Phobos-Grunt will then spend several months studying the planet and its moons from orbit, before landing on Phobos. The current timeline is for arrival in Mars orbit in October 2012 and landing on Phobos in February 2013.[20]

The landing site that has been chosen is a region from 5°S to 5°N, 230° to 235°W.[23]

On Phobos[edit]

The soil sample collection will begin immediately after the lander has touched down on Phobos. Normal collection will last 2–7 days. An emergency mode exists for the case of communications breakdown, which enables the lander to automatically launch the return rocket to deliver the samples to Earth. The samples, which can be up to 0.5 inches (1.3 cm) in diameter, will be collected by a robotic arm. At the end of the arm, there is a pipe-shaped tool which splits to form a claw. The tool contains a piston which will push the sample into a cylindrical container. A light-sensitive photo-diode will confirm whether material collection was successful and will also allow visual inspection of the digging area. The sample extraction device should perform 15 to 20 scoops yielding a total of 3 to 5.5 ounces (85 to 156 g) of soil.[24][3] Because the characteristics of Phobos soil are uncertain, the lander includes another soil-extraction device, a Polish-built drill, which will be used in case the soil turns out to be too rocky for the main scooping device.[12][1]

The return rocket is situated on top of the lander. It will need to accelerate to 35 km/h (22 mph) to escape Phobos' gravity. In order to avoid harming the experiments remaining at the lander, the return vehicle will only ignite its engine once the vehicle has been vaulted to a safe height by springs. It will then begin maneuvers for the eventual trip to Earth, where it is expected to arrive in August 2014.[24]

After the departure of the return vehicle, the lander's experiments will continue in-situ on Phobos' surface for a year. To conserve power, mission control will turn these on and off in a precise sequence. The robotic arm will place more samples in a chamber that will heat it and analyze its spectra. This analysis might determine the presence of easily vaporized substances, such as water.[24]

Return to Earth[edit]

The return stage, with the Phobos soil sample is scheduled to be back on Earth in August 2014. A 11-kg[25] capsule containing the samples (up to 0.2 kg) will be released while in Earth orbit. The conical-shaped capsule will perform a hard landing without a parachute, and it will not have radio equipment.[1] Ground-based radar and optical observations will be used to track the capsule's return. The planned landing site is the Sary Shagan test range in Kazakhstan.[26]

Equipment[edit]

Spacecraft instruments[edit]

- TV system for navigation and guidance[27]

- Gamma ray spectrometer[28]

- Neutron spectrometer[28]

- Alpha X spectrometer[28]

- Mass spectrometer[28]

- Seismometer[28]

- Long-wave radar[28]

- Visual and near-infrared spectrometer[28]

- Dust counter[28]

- Ion spectrometer[28]

- Optical solar sensor[29]

Ground control[edit]

The Mission Control Center was located at the Center for Deep Space Communications (Национальный центр управления и испытаний космических средств (in Russian), Євпаторійський центр дальнього космічного зв'язку (in Ukrainian)) equipped with RT-70 radio telescope near Yevpatoria in the Crimea, Ukraine.[30] Russia and Ukraine agreed in late October 2010 that the European Space Operations Centre in Darmstadt, Germany would control the probe.[31]

Development[edit]

The space mission component development is led by NPO Lavochkin under the leadership of Chief Designer Maxim Martynov.[32]. Phobos soil sampling and downloading have been assigned to the GEOHI RAN Institute of the Russian Academy of Science (Vernadski Institute of Geochemistry and Analytical chemistry) and the integrated scientific studies of Phobos and Mars by remote and contact methods are being developed by the Russian Space Research Institute.[19]

Development started in 2001 and the preliminary design was completed in 2004. The cost of the spacecraft is 1.5 billion rubles ($64.4 million).[3] Total project funding for the timeframe 2009-2012 is about 2.4 billion rubles.[9] If successful, Fobos-Grunt could pave way to a number of Russian interplanetary missions, including missions to the moons of Jupiter, Saturn and Uranus, and asteroid and comet sample return missions.[33]

The Russian Federal Space Agency said 90% of Phobos Grunt is made of new and untested elements. The new instruments are being tested and will be tested during the flight.[31]

Partners[edit]

The Chinese Mars probe Yinghuo-1 will be sent together with Fobos-Grunt.[34] In late 2012, after a 10-11.5 month cruise, Yinghuo-1 will separate and enter a 800×80,000 km equatorial orbit (5° inclination) with a period of three days. The spacecraft is expected to remain on Martian orbit for one year. Yinghuo-1 will focus mainly on the study of the external environment of Mars. Space center researchers will use photographs and data to study the magnetic field of Mars and the interaction between ionospheres, escape particles and solar wind.[35]

A second Chinese payload, the Soil Offloading and Preparation System (SOPSYS), is to be integrated into the instruments of the lander. SOPSYS is a microgravity grinding tool developed by the Hong Kong Polytechnic University.[36][37]

Another payload on Fobos-Grunt is an experiment from the Planetary Society called Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment, or LIFE, which will send 10 types of microorganisms and a natural soil colony of microbes on the three-year round trip. The results may fuel the debate about whether meteorite-riding organisms can spread life throughout the solar system.[6][38]

Two MetNet Mars landers, developed by the Finnish Meteorological Institute, were planned to be included as a payload to the Fobos-Grunt mission.[39][40] Due to delays in MetNet development, the landers were not ready for the previous launch date of Fobos-Grunt, 2009. For the 2011 launch window, which is not as suitable as the 2009 one, weight constraints on the Fobos-Grunt spacecraft required dropping the MetNet landers from the mission.[9]

The Bulgarian Academy of Sciences has also installed its own radiation measurement experiment on Fobos-Grunt.[41]

Criticism[edit]

Barry E. DiGregorio, the director of the International Committee Against Mars Sample Return, criticised the LIFE experiment on the Fobos-Grunt mission as a violation of the Outer Space Treaty of 1967 due to its risk of contaminating Phobos or Mars with the microbial spores and live bacteria it contains. While the mission lands and returns from Phobos, a moon of Mars, the risk to Mars itself is from the possibility of Fobos-Grunt losing control and crash landing on the planet.[42] It is speculated that the heat-resistant extremophile bacteria would be particularly able to survive such a crash, on the basis that heat resistant bacteria Microbispora survived the Space Shuttle Columbia disaster.[43]

However, as stated by Fobos-Grunt Chief Designer Maxim Martynov, the estimates by mission specialists yield much lower probability of reaching the surface of Mars than what is required for Category III of target body/mission type assigned to Fobos-Grunt and defined by COSPAR Planetary protection policy (according to Article IX of the Outer Space Treaty).[44][45]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "Daring Russian Sample Return mission to Martian Moon Phobos aims for November Liftoff". Universe Today. 2011-10-13.

- ^ a b Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. pp. 326–330. ISBN 9780387713540.

- ^ a b c Zaitsev, Yury (July 14, 2008). "Russia to study Martian moons once again". RIA Novosti.

- ^ "Russia to test unmanned lander for Mars moon mission". RIA Novosti. 2010-09-09.

- ^ "China to launch probe to Mars with Russian help in 2009". RIA Novosti. 2008-12-05.

- ^ a b Zak, Anatoly (2008-09-01). "Mission Possible - A new probe to a Martian moon may win back respect for Russia's unmanned space program". AirSpaceMag.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt probe launch is postponed to 2011" (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 2009-09-21. Retrieved 2009-09-21.

- ^ "Russia delays Mars probe launch until 2011: report". Space Daily. September 16, 2009.

- ^ a b c Zak, Anatoly. "Preparing for flight". Russianspaceweb.com. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (2009-04). "Russia to Delay Martian Moon Mission". IEEE Spectrum. Retrieved 2009-05-26.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|date=(help) - ^ "Industry Insiders Foresaw Delay of Russia's Phobos-Grunt". Space News. 2009-10-05.

- ^ a b "Difficult rebirth for Russian space science". BBC News. 2010-06-29.

- ^ Phobos-Grunt arrives to Baikonur

- ^ a b Fobos-Grunt sent to Baikonur (in Russian)

- ^ We need your support in the project "Phobos-Soil", because Phobos-soil project

- ^ "Phobos-Grunt to be launched to Mars on Nov 8". Interfax News. 4 October 2011. Retrieved 5 October 2011.

- ^ "Fobos-Grunt space probe is moved to a refueling station". Roscosmos. October 21, 2011. Retrieved 2011-10-21.(in Russian)

- ^ "Russia Fuels Phobos-Grunt and sets Mars Launch for November 9". universetoday. 29 October 2011. Retrieved 1 November 2011.

- ^ a b c Cite error: The named reference

ESA_PMRwas invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b "Timeline for the Phobos Sample Return Mission (Phobos Grunt)". Planetary Society. October 27, 2010. Retrieved 2010-10-28.

- ^ Korablev, O. "Russian programme for deep space exploration" (PDF). Space Research Institute (IKI). p. 14.

- ^ "Living Interplanetary Flight Experiment (LIFE)". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "Images of Mars Express' closest ever flyby at Phobos". DLR. July 30, 2008.

- ^ a b c Zak. "Mission Possible".

- ^ Phobos Soil - Spacecraft European Space Agency

- ^ The mission scenario of the Phobos-Grunt project Anatoly Zak

- ^ "Optico-electronic Instruments for the Phobos-Grunt Mission". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Harvey, Brian (2007). "Resurgent - the new projects". The Rebirth of the Russian Space Program (1st ed.). Germany: Springer. ISBN 9780387713540.

- ^ "Optical Solar Sensor". Space Research Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences. Retrieved 2009-07-20.

- ^ Russian spacecraft for Fobos-Grunt program to be controlled from Yevpatoria, Kyiv Post (June 25, 2010)

- ^ a b "Russia's Phobos Grunt to head for Mars on November 9". Itar Tass. 25 October 2011. Retrieved 27 October 2011.

- ^ Biography of Maxim Martynov(in Russian)

- ^ Zak, Anatoly (April 15, 2008). "Russian space program: a decade review (2000–2010)". Russian Space Web.

- ^ Bergin, Chris (May 21, 2007). "With a Russian hitch-hike, China heading to Mars". NASAspaceflight.

- ^ "China and Russia join hands to explore Mars". People's Daily Online. May 30, 2007. Retrieved May 31, 2007.

- ^ Zhao, Huanxin (March 27, 2007). "Chinese satellite to orbit Mars in 2009". China Daily.

- ^ "HK triumphs with out of this world invention". HK Trader. May 1, 2007.

- ^ "LIFE Experiment: Phobos". The Planetary Society.

- ^ "MetNet Mars Precursor Mission". Finnish Meteorological Institute.

- ^ "Space technology – a forerunner in Finnish-Russian high-tech cooperation". Energy & Enviro Finland. October 17, 2007.

- ^ [http://www.space.bas.bg/ Проект “Люлин-Фобос” - “Радиационно сондиране по трасето Земя-Марс в рамките на проекта «Фобос-грунт»”. Международен проект по програмата за академичен обмен между ИКСИ-БАН и ИМПБ при АН на Русия - (2011-2015). ], Bulgarian Academy of Sciences

- ^ DiGregorio, Barry E. (2010-12-28). "Don't send bugs to Mars". New Scientist. Retrieved 8 January 2011.

- ^ http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0019103505004951

- ^ Russia resumes missions to outer space: what is after Phobos?(in Russian)

- ^ COSPAR Planetary Protection Policy

- M. Ya. Marov, V. S. Avduevsky, E. L. Akim, T. M. Eneev, R. S. Kremnevich, S. D. Kulikovich, K. M. Pichkhadzec, G. A. Popov, G. N. Rogovshyc (2004). "Phobos-Grunt: Russian sample return mission". Advances in Space Research. 33 (12): 2276–2280. Bibcode:2004AdSpR..33.2276M. doi:10.1016/S0273-1177(03)00515-5.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links[edit]

- Phobos-Grunt on NPO Lavochkin website (in Russian)

- Project home page (Russian Space Research Institute) (in English)

- Phobos-Grunt on RussianSpaceWeb

- 2010 status

- Detailed mission profile on YouTube (in Russian)