User:MyCatIsAChonk/sandbox2

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky[a] (17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882 – 6 April 1971) was

Life[edit]

Early life in Russia, 1882–1901[edit]

Igor Fyodorovich Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum, Russia—a town now called Lomonosov, about fifty kilometers west of Saint Petersburg—on 17 June [O.S. 5 June] 1882.[1][2] His mother, Anna Kirillovna Stravinskaya (née Kholodovsky), came from a family of landowning noblemen, and was educated in singing and piano.[3][4] His father, Fyodor Ignatyevich Stravinsky, was an established bass at the Mariinsky Theatre in Saint Petersburg, descended from a line of Polish landowners.[4][5] The name "Stravinsky" was of Polish origin, deriving from the Strava river in eastern Poland. The family was originally beared the name Soulima-Stravinsky, bearing the likely-German Soulima coat of arms, but "Soulima" was dropped after Russia's annexation during the partitions of Poland.[6][7]

Igor Stravinsky was born in Oranienbaum while his family vacationed there for the summer;[8][9] the families' primary residence was an apartment along Kryukov Canal in central Saint Petersburg, near the Mariinsky Theatre. He was baptised hours after birth and joined to the Russian Orthodox Church in the St. Nicholas Cathedral.[5] Constantly in fear of his hot-tempered father and indifferent towards his mother, Igor lived there for the first 27 years of his life with three siblings: Roman and Yury, his older siblings that irritated him immensely, and Gury, his close younger brother with whom he found "the love and understanding denied to us by our parents".[10][5] Igor was educated by the families' governess until age 11, when he began attending the Second Saint Petersburg Gymnasium, a school he recalled hating and having few friends in.[11][12]

From age 9, Stravinsky was taught piano privately.[13] He recalled that his parents saw no musical talent in him due to his lack of technical skills;[14] the young pianist frequently improvised instead of practicing assigned pieces.[15] Stravinsky's excellent sight-reading skill prompted him to frequently read vocal scores from his father's vast personal library.[16][4] At around age 10, he began regularly attending performances at the Mariinsky Theatre, where he was introduced to Russian repertoire as well as Italian and French opera;[17] by 16, he attended rehearsals at the theater five or six days a week.[13] By age fourteen, Stravinsky mastered Mendelssohn's Piano Concerto No. 1, and at age fifteen finished a piano reduction of a string quartet by Alexander Glazunov.[18][19]

Higher education, 1901–1909[edit]

Student compositions[edit]

Despite his musical passion and ability, Stravinsky's parents expected he study law at the University of Saint Petersburg, and he enrolled in 1901. However, according to his own account, he was a bad student and attended few of the optional lectures.[20][21] In exchange for agreeing to attend law school, his parents allowed for lessons in harmony and counterpoint.[22] One law student who Stravinsky befriended was Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov, son of the leading Russian composer Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov.[b] During summer vacation of 1902, Stravinsky traveled with Vladimir Rimsky-Korsakov to Heidelberg – where the latter's family was staying – bringing a portfolio of pieces to demonstrate to the Nikolai Rimsky-Korsakov. While the elder composer was not stunned, he was impressed enough to insist that Stravinsky continue lessons but advised against him entering the Saint Petersburg Conservatory due to its rigorous environment. Importantly, Rimsky-Korsakov agreed to personally advise Stravinsky on his compositions.[22][25]

After Stravinsky's father died in 1902 and the young composer became more independent, he became increasingly involved in Rimsky-Korsakov's circle of artists.[26][27] His first major task from his new teacher was the four-movement Piano Sonata in F-sharp minor in the style of of Glazunov and Tchaikovsky – he paused temporarily to write a cantata for Rimsky-Korsakov's 60th birthday celebration, which the elder composer described as "not bad". Soon after finishing the sonata, the student began his large-scale Symphony in E-flat,[c] the first draft of which he finished in 1905.[22] The student's first public premiere came in 1905, when the dedicatee of the Piano Sonata, Nikolay Richter, performed it at a regular performance gathering at the Rimsky-Korsakov household.[22]

After the events of Bloody Sunday in January 1905 caused the university to close, Stravinsky was not able to take his final exams, resulting in him graduating with a half-diploma. As he began spending more time in Rimsky-Korsakov's circle of artists, the young composer became increasingly cramped in the conservative atmosphere: modern music was questioned, and concerts of contemporary music were looked down upon.[22] Nevertheless, Stravinsky remained loyal to Rimsky-Korsakov – the musicologist Eric Walter White suspected that the composer had to comply with his teachers' style in order to make it in the Russian music scene.[27] Stravinsky later wrote that his teachers' musical conservatism was justified, and helped him build the foundation that would become the base of his style.[30]

First marriage[edit]

In August 1905, Stravinsky announced his engagement to Yekaterina Nosenko, his first cousin whom he met in 1890 during a family trip.[22] He later recalled:

From our first hour together we both seemed to realize that we would one day marry—or so we told each other later. Perhaps we were always more like brother and sister. I was a deeply lonely child and I wanted a sister of my own. Catherine, who was my first cousin, came into my life as a kind of long-wanted sister ... We were from then until her death extremely close, and closer than lovers sometimes are, for mere lovers may be strangers though they live and love together all their lives ... Catherine was my dearest friend and playmate ... and from then until we grew into our marriage.[31]

The two had grown close during family trips, encouraging each other's interest in painting and drawing, swimming together often, going on wild raspberry picks, helping build a tennis court, playing piano duet music, and later organizing group readings with their other cousins of books and political tracts from Fyodor Stravinsky's personal library.[32] In July 1901, Stravinsky expressed infatuation with Lyudmila Kuxina, Nosenko's best friend, but after the self-described "summer romance" had ended, Nosenko and Stravinsky's relationship began developing into a furtive romance.[33] Between their intermittent family visits, Nosenko studied painting at the Académie Colarossi in Paris.[34] The two married on January 24, 1906, at the Church of the Annunciation five miles north from Saint Petersburg – because marriage between first cousins was banned, they procured a priest who did not ask of their identities, and the ceremony was attended only by Rimsky-Korsakov's sons.[35] They soon had two children: Théodore, born in 1907, and Ludmila, born the following year.[36]

After finishing the many revisions of the Symphony in E-flat in 1907, Stravinsky wrote Faun and Shepherdess, a setting of three Pushkin poems for mezzo-soprano and orchestra.[28] Rimsky-Korsakov organized the first public premiere of his student's work with the Imperial Court Orchestra in April 1907, programming the Symphony in E-flat and Faun and Shepherdess.[37][22] Rimsky-Korsakov's death in June 1908 caused Stravinsky deep mourning, and he recalled the Funeral Song he composed in memory of his teacher was "the best of my works before [his 1910 ballet] The Firebird".[38][39]

International fame, 1909–1920[edit]

Ballets for Diaghilev[edit]

By 1909, Stravinsky had composed two more pieces, Scherzo fantastique and Feu d'artifice, both lively orchestral movements featuring bright orchestration and unique harmonic techniques.[22] Attending a performance of both works in February 1909 was the impresario Sergei Diaghilev, who had founded the art magazine Mir iskusstva in 1898,[40] but after it ended publication in 1904, he turned towards Paris for artistic opportunities rather than his native Russia.[41][42] In 1907, Diaghilev presented a five-concert series of Russian music at the Paris Opera; the next year, he staged the Paris premiere of Rimsky-Korsakov's version of Boris Godunov.[41][43] The vivid color and tone of Stravinsky's works intrigued Diaghilev, and soon after, the impresario commissioned Stravinsky to orchestrate music by Chopin for the ballet Les Sylphides.[44][45] These were presented by Diaghilev's ballet company, the Ballets Russes, in April 1909, and while the company scored successes with Parisian audiences, Stravinsky was working on the Act I of his first opera The Nightingale.[46]

As the Ballets Russes faced financial issues, Diaghilev wanted a new ballet with distinctly Russian music and design, something that had recently become popular with French and other Western audiences; his company settled on the subject of the mythical Firebird.[47][48][49] Diaghilev asked multiple composers to write the ballet's score, including Nikolai Tcherepnin and Anatoly Lyadov, but after none committed the project,[50] the impresario turned to the 27-year-old Stravinsky, who gladly accepted the task.[51][52] During the ballet's production, Stravinsky became close with Diaghilev's artistic circle, who were impressed by his enthusiasm to learn more about non-musical art forms.[51] The Firebird premiered in Paris on 25 June 1910 to widespread critical acclaim, making Stravinsky an overnight sensation.[53] Many critics praised the composer's alignment with Russian nationalist music.[54] Stravinsky recalled that after the premiere and subsequent performances, he met many figures in the Paris art scene; Claude Debussy was brought on stage after the premiere, and he invited Stravinsky to dinner, beginning a lifelong friendship between the two composers.[d][53][56]

The Stravinsky family moved to Lausanne, Switzerland for the birth of their third child, Soulima, and it was there that Stravinsky began work on a konzertstück for piano and orchestra depicting the tale of a puppet coming to life.[53][57] After Diaghilev heard the early drafts, he convinced Stravinsky to turn it into a ballet for the 1911 ballet season.[53][58] Petrushka premiered in Paris on 13 June 1911 to equal popularity as The Firebird, and Stravinsky became settled as one of the most advanced young composers of his time.[59][60]

While composing The Firebird, Stravinsky had an idea for a work about "a solemn pagan rite: sage elders, seated in a circle, watched a young girl dance herself to death". He immediately shared the idea with Nicholas Roerich, a friend and painter of pagan subjects. Upon sharing the idea with Diaghilev, the impresario excitedly agreed to commission the work.[57][61] After the premiere of Petrushka, Stravinsky settled at his family's residence in Ustilug and fleshed out the details of the ballet with Roerich, later finishing the work in Clarens, Switzerland.[62] The ballet, depicting pagan rituals in Slavonic tribes,[63] used many avant-garde techniques, including uneven rhythms and metres, superimposed harmonies, atonality, and massive instrumentation.[64] With radical choreography by the young Vaslav Nijinsky, the ballet's experimental nature caused a sensation at its premiere at the Théâtre des Champs-Élysées on 29 May 1913.[62][65]

Switzerland[edit]

Soon after, Stravinsky was admitted to a hospital for typhoid fever and stayed in recovery for five weeks; many friends visited the composer, including Debussy, Manuel de Falla, Maurice Ravel,[f] and Florent Schmitt. Upon returning to his family in Ustilug, he continued work on his opera The Nightingale, now with an official commission from the Moscow Free Theatre.[62][67] In early 1914, Stravinsky's wife contracted tuberculosis and was admitted to a sanatorium in Leysin, Switzerland, where the couple's fourth child, Maria Milena, was born.[68] Here Stravinsky finished The Nightingale, but after the Moscow Free Theatre collapsed before the premiere, Diaghilev agreed to stage the opera.[69] The 1914 premiere was somewhat successful; critics' high expectations after the tumultuous Rite of Spring were not met, though fellow composers were impressed by the work.[70]

In early July 1914, while his family resided in Switzerland near the sick Yekaterina Stravinsky, the composer traveled to Russia to retrieve texts for his next work, a ballet-cantata depicting Russian wedding traditions titled Les noces. Soon after he returned, World War I began, and the Stravinskys permanently resided in Switzerland until 1920,[g] initially living in Clarens and later Morges.[72][73][74] During the first months of the war, the composer intensely researched Russian folk poetry and prepared librettos for numerous works to be composed in the coming years, including Les noces, Renard, Pribaoutki, and other song cycles.[75] Stravinsky met numerous Swiss-French artists during his time in Morges, including the author C. F. Ramuz, with whom he collaborated on the small theatre work L'Histoire du soldat. The eleven-musician and two-dancer show was designed for easy travel, but after a premiere run funded by Werner Reinhart, all other performances were cancelled due to the Spanish flu epidemic.[74]

Stravinsky's income from performance royalties was suddenly cut off when his Germany-based publisher suspended operations due to the war.[76] To keep his family afloat, the composer sold numerous manuscripts and accepted commissions from wealthy impresarios; one such commission included Renard, a theatre work completed in 1916 upon a request from Princesse Edmond de Polignac.[77] Additionally, Stravinsky made a new concert suite from The Firebird and sold it to a London publisher in an attempt to regain copyright control over the ballet.[74] Les noces for Diaghilev continued to organize Ballets Russes shows across Europe, including two charity concerts for the Red Cross where Stravinsky made his conducting debut with The Firebird.[78] When the Ballets Russes traveled to Rome in April 1917, the composer met the artist Pablo Picasso, with whom Stravinsky adventured around Italy; a commedia dell'arte the two saw in Naples inspired the ballet Pulcinella, which premiered in Paris in May 1920 with designs by Picasso.[79][74]

France, 1920–1939[edit]

Carantec[edit]

After the war ended, Stravinsky decided that his residence in Switzerland was too far from Europe's musical activity, and briefly moved his family to Carantec, France.[80] In September 1920, they relocated to the home of Coco Chanel, an associate of Diaghilev's, where Stravinsky composed his early neoclassical work the Symphonies of Wind Instruments.[81][82] After his relationship with Chanel developed into an affair, Stravinsky relocated his family to the white émigré-hub Biarritz in May 1921, partly due to the presence of his other lover Vera de Bosset.[81] Though de Bosset divorced her husband and Yekaterina Stravinsky became aware of her husband's infidelity, the Stravinskys never divorced, likely due to his refusal to seperate.[h][84]

In 1921, Stravinsky signed a contract with the player piano company Pleyel to create piano roll arrangements of his music.[85] He received a studio at their factory on the Rue Rochechouart, where he reorchestrated Les noces for a small ensemble including player piano. Though player pianos quickly went out of fashion, the composer transcribed many of his major works for the mechanical pianos, and he worked at the Rochechouart factory until 1933.[84][86] Stravinsky signed another contract in 1924, this time with the Aeolian Company in London, producing rolls that included short spoken introductions by the composer.[87] His involvement with player pianos ended in 1930 when the Aeolian Company's London branch was dissolved.[86]

The mutual interest in Pushkin shared by Stravinsky and Diaghilev led to a Mavra, a comic opera began in 1921 that exhibited the composer's rejection of Rimsky-Korsakov's style and his turn towards classic Russian operatists like Tchaikovsky, Glinka, and Dargomyzhsky.[84][88] Yet, after the 1922 premiere, the work's tame style – compared to the innovative music he'd come to be known for – disappointed critics.[89] In 1923, Stravinsky finished orchestrating Les noces, settling on a percussion ensemble including four pianos. The Ballets Russes staged the ballet-cantata that June,[i] and although it initially received moderate reviews,[91] the London production received a flurry of critical attacks, leading the writer H. G. Wells to publish an open letter in support of the work.[92][93] Around this time, Stravinsky also began conducting and performing piano more: he conducted the premiere of his Octet in 1923, and the Piano Concerto of 1924 was premiered with himself as soloist, soon after taking the work on tour and performing it in over 40 concerts.[84][94][95]

Nice and international touring[edit]

The Stravinsky family moved again in September 1924 to Nice, France. Much of the composer's time was divided between his family in Nice and performances in Paris and on tour elsewhere with de Bosset usually accompanying him.[84] At this time, Stravinsky was going through a spiritual crisis onset by meeting Father Nicolas, a priest near his new home.[90] He had abandon the Russian Orthodox Church during his teenage years, but after meeting Father Nicolas and reconnecting with the church, he began regularly attending church starting in 1926.[96][97] From then until the early 1940s, Stravinsky diligently attended services, participated in charity work, and studied religious texts.[98] The composer later wrote that he was contacted by God at a service at the Basilica of Saint Anthony of Padua, leading him to write his first religious composition, the Pater Noster for a cappella choir.[99]

In 1925, Stravinsky asked the French writer and artist Jean Cocteau to write the libretto for an operatic setting of Sophocles's tragedy Oedipus Rex in Latin.[100] The May 1927 premiere of Oedipus rex was staged as a concert performance since there was too little time and money to present it as a full opera, and Stravinsky attributed the work's failure to its programming between two glittery ballets.[101][102] Furthermore, the influence from Russian Orthodox vocal music and Classical period composers like Handel were not well-received in the press after the May 1927 premiere; neoclassicism was a bad practice to critics, and Stravinsky had to publicly assert that his music was not part of the movement.[103][104] This reception from Parisian critics was not improved by Stravinsky's next ballet, Apollon musagète, which depicts the birth and apotheosis of Apollo using a calm 18th-century ballet de cour musical style.[j][100][105]

A new commission for a ballet from Ida Rubinstein in 1928 led Stravinsky again to Tchaikovsky. Basing the music off of romantic ballets like Swan Lake and borrowing many themes from Tchaikovsky, Stravinsky wrote The Fairy's Kiss with Hans Christian Andersen's tale The Ice-Maiden as the subject.[106][100] The November 1928 premiere was not a great success, likely due to the disconnect between each of the ballet's sections and the mediocre choreography of which Stravinsky disapproved.[107][108] Diaghilev's fury with Stravinsky for accepting a ballet commission from someone else caused an intense feud between the two, one that lasted until the impresario's death in August 1929.[k][111] Most of 1929 was spent composing a new solo piano work, the Capriccio, and touring across Europe to conduct and perform piano;[100][112] its success after the December 1929 premiere caused a flurry of performance requests from many orchestras.[113] A commission from the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1930 for a symphonic work led Stravinsky back to Latin texts, this time from the book of Psalms.[100][114] Between touring concerts, he composed the choral Symphony of Psalms, a deeply religious work that premiered in December 1930.[115]

Last years in France[edit]

While touring in Germany, Stravinsky visited his publisher's home and met the violinist Samuel Dushkin, who convinced him to compose the Violin Concerto with his help on the solo part.[100][116] Impressed by Dushkin's ability and understanding of music, the composer wrote more music for violin and piano and rearranged some of his earlier music to be performed alongside the Concerto while on tour until 1933.[117][118] That year, Stravinsky received another ballet commission from Ida Rubenstein for a setting of a poem by André Gide.[l] The resulting melodrama Perséphone only received three performances in 1934 due to its lukewarm reception, and Stravinsky's disdain towards the work was evident in his later suggestion that the libretto be rewritten by another author.[100][120][121] On 10 June 1934, Stravinsky became a naturalised French citizen, protecting all his future works under copyright in France and the United States. His family subsequently moved to an apartment on the Rue du Faubourg Saint-Honoré in Paris, where he began writing an autobiography with the help of Walter Nouvel published in two volumes 1935 and 1936.[100][122]

After the short run of Perséphone, Stravinsky embarked on a successful three-month United States tour with Dushkin; he visited South America for the first time the following year.[123][124] The composer's son Soulima was an excellent pianist, having performed the Capriccio in concert with his father conducting. Continuing a line of solo piano works, the elder Stravinsky composed the Concerto for Two Pianos to be performed by them both, and they toured the work through 1936.[125] Around this time came three American-commissioned works:[124] the ballet Jeu de cartes for George Balanchine,[126] the Brandenburg Concerto-like work Dumbarton Oaks,[127] and the Symphony in C for the Chicago Symphony Orchestra's 50th anniversary.[128] Stravinsky's last years in France from late 1938 to 1939 were marked by the deaths of his eldest daughter, his wife, and his mother, the former two from tuberculosis.[121][129] In addition, the increasingly hostile reception towards his music and failed run for a seat in the Institut de France further dissociated the man from France,[130][122] and shortly after the beginning of World War II in September 1939 he moved to the United States.[124]

United States, 1939–1971[edit]

Music[edit]

Most of Stravinsky's student works were composed for assignments from his teacher Rimsky-Korsakov, being mainly influenced by Rimsky-Korsakov and other Russian composers.[131] His first three ballets, The Firebird, Petrushka, and The Rite of Spring, were the beginning of his international fame and deviation from 19th-century styles.[131][132] Stravinsky's music is often divided into three periods of composition: his Russian period (1913–1920), where he was greatly influenced by Russian artists and folklore;[133] his neoclassical period (1920–1951), where Stravinsky turned towards techniques and themes from the Classical period;[82][134] and his serial period (1954–1968), where Stravinsky used serial composition techniques pioneered by composers of the Second Viennese School.[135][136]

Student works, 1898–1907[edit]

Stravinsky's time before meeting Diaghilev was spent learning from Rimsky-Korsakov and his collaborators.[131] Only three works survive from before Stravinsky met Rimsky-Korsakov in August 1902: "Tarantella" (1898), Scherzo in G minor (1902), and The Storm Cloud, the first two being works for piano and the last for voice and piano.[137][138] Stravinsky's first assignment from Rimsky-Korsakov was the four-movement Piano Sonata in F♯ minor, which was also his first work to be performed in public.[139][140] Rimsky-Korsakov often gave Stravinsky the task of orchestrating various works to allow him to analyze the works' form and structure.[141] A number of Stravinsky's student compositions were performed at Rimsky-Korsakov's gatherings at his home; these include a set of bagatelles, a "chanson comique", and a cantata, showing the use of classical musical techniques that would later define Stravinsky's neoclassical period.[141] The musicologist Stephen Walsh described this time in Stravinsky's musical career as "aesthetically cramped" due to the "cynical conservatism" of Rimsky-Korsakov and his music.[142] Rimsky-Korsakov thought the Symphony in E-flat (1907) was swayed too much by Glazunov's style, and disliked the modernist influence on Faun and Shepherdess (1907).[143]

First three ballets, 1910–1913[edit]

After the vivid orchestration of Scherzo fantastique (1909) and Feu d'artifice (1909) attracted the attention of Diaghilev, he commissioned Stravinsky to orchestrate Chopin's Nocturne in A-flat major and Grande valse brillante in E-flat major for the new ballet Les Sylphides, and commissioned Stravinsky's first ballet, The Firebird, a few months after.[144]

The Firebird used a harmonic structure that Stravinsky called "leit-harmony", a portmanteau of leitmotif and harmony used by Rimsky-Korsakov in his opera The Golden Cockerel.[145] The "leit-harmony" was used to juxtapose the protagonist, the Firebird, and the antagonist, Koschei the Deathless: the Firebird was associated with whole-tone phrases and Koschei was associated with octatonic harmony.[146] Stravinsky later wrote how he composed The Firebird in a state of "revolt against Rimsky", and that he "tried to surpass him with ponticello, col legno, flautando, glissando, and fluttertongue effects".[147]

Stravinsky's second ballet for the Ballets Russes, Petrushka, is where Stravinsky defined his musical character.[148] Originally meant to be a konzertstück for piano and orchestra, Diaghilev convinced Stravinsky that he should instead compose it as a ballet instead for the 1911 season.[149] The Russian influence can be seen in the use of a number of Russian folk tunes in addition to two waltzes by Viennese composer Joseph Lanner and a French music hall tune (La Jambe en bois or The Wooden Leg).[m] Stravinsky also used a folk tune from Rimsky-Korsakov's opera The Snow Maiden, showing his continued influence on the music of Stravinsky.[150]

Stravinsky's third ballet, The Rite of Spring, caused a sensation at the premiere due to the avant-garde nature of the work.[57] Stravinsky had begun to experiment with polytonality in The Firebird and Petrushka, but for The Rite of Spring, he "pushed [it] to its logical conclusion," as Eric Walter White describes it.[151] In addition, the complex metre in the music consists of phrases combining conflicting time signatures and odd accents, such as the "jagged slashes" in the "Sacrificial Dance".[152][151] Both polytonality and unusual rhythms can be heard in the chords that open the second episode, "Augurs of Spring", consisting of an E♭ dominant 7 superimposed on an F♭ major triad written in an uneven rhythm, Stravinsky shifting the accents seemingly at random to create asymmetry.[153][154] The Rite of Spring is one of the most famous and influential works of the 20th century; the musicologist Donald Jay Grout described it as having "the effect of an explosion that so scattered the elements of musical language that they could never again be put together as before."[155]

Russian period, 1913–1920[edit]

The musicologist Jeremy Noble says that Stravinsky's "intensive researches into Russian folk material" took place during his time in Switzerland from 1914 to 1920.[133] The composer Béla Bartók considered Stravinsky's Russian period to have begun in 1913 with The Rite of Spring due to the works' use of Russian folk songs, themes, and techniques.[156] The use of duple or triple metres was especially prevalent in Stravinsky's Russian period music; while the pulse may have remained constant, the time signature would often change to constantly shift the accents.[157]

While Stravinsky did not use as many folk melodies as he had in his first three ballets, Stravinsky used folk poetry often.[158] The ballet-canata Les noces was based on texts from a collection of Russian folk poetry by Pyotr Kireevsky,[75][159] and his opera-ballet Renard was based on a folktale collected by Alexander Afanasyev.[160][161] Many of Stravinsky's Russian period works featured animal characters and themes, likely due to inspiration from nursery rhymes he read with his children.[162] Stravinsky also used unique theatrical styles. Les noces blended the staging of ballet with the instrumentation of cantata, a unique production described on the score as "Russian Choreographic Scenes".[163] In Renard, the voices were placed in the orchestra, as they were meant to accompany the action on stage.[162] L'Histoire du soldat was composed in 1918 with the Swiss novelist Charles F. Ramuz as a "quirky musical-theatre work" for dancers, a narrator, and a septet.[164] The work mixed the Russian folktales in the narrative with common musical structures of the time, like the tango, waltz, rag, and chorale.[165] According to Walsh, Stravinsky's music was always influenced by his Russian roots, and despite their decreased use in his later output, he maintained continuous musical innovation.[166]

Neoclassical period, 1920–1951[edit]

In Naples, Italy, Stravinsky saw a commedia dell'arte featuring the "great drunken lout" of a character Pulcinella, who would later become the subject of his ballet of the same name.[167] Officially begun in 1919,[168] Pulcinella was commissioned by Diaghilev after he proposed the idea of a ballet based on music by Giovanni Battista Pergolesi, Domenico Gallo, and others whose music was published under Pergolesi's name.[169][170] Composing a work based on harmonic and rhythmic systems by a late-Baroque era composer was the beginning of Stravinsky's turn towards 18th-century music.[169] Although the musicologist Jeremy Noble considers Stravinsky's neoclassical period to have begun in 1920 with his Symphonies of Wind Instruments,[82] Bartók argues that the period "really starts with his Octet for Wind Instruments, followed by his Concerto for Piano ..."[171] During this period, Stravinsky used techniques and themes from the Classical period of music.[171]

Greek mythology was a common theme in Stravinsky's neoclassical works. His first Greek mythology-based work was the ballet Apollon musagète (1927), choosing the leader of the Muses and the god of art Apollo as the subjects.[172] Stravinsky would use themes from Greek mythology in future works like Oedipus rex (1927), Persephone (1935), and Orpheus (1947).[173] The musicologist Richard Taruskin writes that Oedipus rex was "the product of Stravinsky's neo-classical manner at its most extreme," and that musical techniques "thought outdated" were juxtaposed against oddly contemporary techniques.[174] In addition, Stravinsky turned towards older musical structures and modernised them.[175][176] His Octet (1923) uses the sonata form, modernising it by disregarding the standard ordering of themes and traditional tonal relationships for different sections.[175] Baroque counterpoint was used throughout the choral Symphony of Psalms.[177]

Stravinsky's neoclassical period ended in 1951 with the opera The Rake's Progress.[178][179] Taruskin described the opera as "the hub and essence of 'neo-classicism'". He points out how the opera contains numerous references to Greek mythology and other operas like Don Giovanni and Carmen, but still "embody[s] the distinctive structure of a fairy tale". Stravinsky was inspired by the operas of Mozart in composing the music, but other scholars also point out influence from Handel, Gluck, Beethoven, Schubert, Weber, Rossini, Donizetti, and Verdi.[180][181] The Rake's Progress has become an important work in opera repertoire, being "[more performed] than any other opera written after the death of Puccini", according to Taruskin.[182]

Serial period, 1954–1968[edit]

In the 1950s, Stravinsky began using serial compositional techniques, such as the twelve-tone technique originally devised by Arnold Schoenberg.[183] Noble writes that this time was "the most profound change in Stravinsky's musical vocabulary", partly due to Stravinsky's newfound interest in the music of the Second Viennese School after meeting Robert Craft.[135]

Stravinsky first experimented with non-twelve-tone serial techniques in small-scale works such as the Cantata (1952), the Septet (1953) and Three Songs from Shakespeare (1953). The first of his compositions fully based on such techniques was In Memoriam Dylan Thomas (1954). Agon (1954–57) was the first of his works to include a twelve-tone series and the second movement from Canticum Sacrum (1956) was the first piece to contain a movement entirely based on a tone row.[136] Agon's unique tonal structure was significant to Stravinsky's serial music; the work begins diatonic, moves towards full 12-tone serialism in the middle, and returns to diatonicism in the end.[184] Stravinsky returned to sacred themes in works such as Canticum Sacrum, Threni (1958), A Sermon, a Narrative and a Prayer (1961), and The Flood (1962). Stravinsky used a number of concepts from earlier works in his serial pieces; for example, the voice of God being two bass voices in homophony seen in The Flood was previously used in Les noces.[184] Stravinsky's final large-scale work, the Requiem Canticles (1966), made use of a complex four-part array of tone rows throughout, showing the evolution of Stravinsky's serialist music.[185][184] Noble describes the Requiem Canticles as "a distillation both of the liturgical text and of his own musical means of setting it, evolved and refined through a career of more than 60 years".[186]

Influence from other composers can be seen throughout this period. Stravinsky was heavily influenced by Schoenberg, not only in his use of the twelve-tone technique, but also in the distinctly "Schoenbergian" instrumentation of the Septet and the similarities between Schoenberg's Klangfarbenmelodie and Stravinsky's Variations.[135][184] Stravinsky also used a number of themes found in works by Benjamin Britten,[184] later commenting about the "many titles and subjects [I have shared] with Mr. Britten already".[187] In addition, Stravinsky was very familiar with the works of Anton Webern, being one of the figures who inspired Stravinsky to consider serialism a possible form of composition.[188]

Influences[edit]

Artistic[edit]

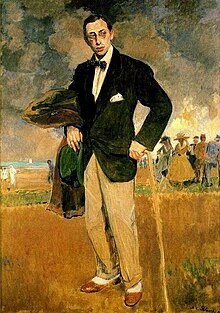

Stravinsky worked with some of the most famous artists of his time, many of whom he met after the premiere of The Firebird.[132] Diaghilev was one of the composer's most prominent artistic influences, having introduced him to composing for the stage and bringing him international fame with his first three ballets.[189] Through the Ballets Russes and Diaghilev, Stravinsky worked with figures like Vaslav Nijinsky, Léonide Massine,[132] Alexandre Benois,[132] Michel Fokine, and Léon Bakst.[41] The composer's interest in art propelled him to develop a strong relationship with Picasso, whom he met in 1917.[190] From 1917 to 1920, the two engaged in an artistic dialogue in which they exchanged small-scale works of art to each other as a sign of intimacy, which included the famous portrait of Stravinsky by Picasso,[191] and a short sketch of clarinet music by Stravinsky.[192] This exchange was essential to establish how the artists would approach their collaborative space in Ragtime and Pulcinella.[193][194]

Literary[edit]

Stravinsky displayed a taste in literature that was wide and reflected his constant desire for new discoveries.[195] The texts and literary sources for his work began with interest in Russian folklore.[196][133] After moving to Switzerland in 1914, Stravinsky began gathering folk stories from numerous collections, which were later used in works like Les noces, Renard, Pribaoutki, and various songs.[75] Many of Stravinsky's works, including The Firebird, Renard, and L'Histoire du soldat were inspired by Alexander Afanasyev's famous collection Russian Folk Tales.[197][160][198] Collections of folk music influenced Stravinsky's music; numerous melodies from The Rite of Spring were found in an anthology of Lithuanian folk songs.[199]

An interest in the Latin liturgy began shortly after Stravinsky rejoined the church in 1926, beginning with the composition of his first religious work in 1926 Pater Noster, written in Old Church Slavonic.[200][201] He later used three psalms from the Latin Vulgate in his Symphony of Psalms for orchestra and mixed choir.[202][203] Many works in the composer's neoclassical and serial periods used (or were based on) liturgical texts.[201][204]

Stravinsky worked with many authors throughout his career. He first worked with the Swiss novelist Charles F. Ramuz on L'Histoire du soldat in 1918, who wrote the text and helped form the idea.[164] In 1933, Ida Rubinstein commissioned Stravinsky to set music to a poem by André Gide, later becoming the melodrama Persephone.[205] The two collaborated well at first, but disagreements over the text caused Gide to leave the project.[206] The story of The Rake's Progress was first conceived by Stravinsky and W. H. Auden, the latter of whom wrote the libretto with Chester Kallman.[207][208] Stravinsky befriended many other authors as well, including T.S. Eliot,[195] Aldous Huxley, Christopher Isherwood, and Dylan Thomas,[209] the last of whom Stravinsky began working with on an opera in 1953 but stopped due to Thomas's death.[210]

Recordings[edit]

Paste old section?

See Pictures and Documents page 308

Writings[edit]

Stravinsky published a number of books throughout his career, almost always with the aid of a (sometimes uncredited) collaborator. In his 1936 autobiography, Chronicle of My Life, which was written with the help of Walter Nouvel, Stravinsky included his well-known statement that "music is, by its very nature, essentially powerless to express anything at all".[211] With Alexis Roland-Manuel and Pierre Souvtchinsky, he wrote his 1939–40 Harvard University Charles Eliot Norton Lectures, which were delivered in French and first collected under the title Poétique musicale in 1942 and then translated in 1947 as Poetics of Music.[n] In 1959, several interviews between the composer and Craft were published as Conversations with Igor Stravinsky, which was followed by a further five volumes over the following decade.[212]

Books and articles are selected from Appendix E of Eric Walter White's Stravinsky: The Composer and His Works and Stephen Walsh's profile of Stravinsky on Oxford Music Online.[213][214]

Books[edit]

- Stravinsky, Igor (1936). Chronicle of My Life. London: Gollancz. OCLC 1354065. Originally published in French as Chroniques de ma vie, 2 vols. (Paris: Denoël et Steele, 1935), subsequently translated (anonymously) as Chronicle of My Life. This edition reprinted as Igor Stravinsky – An Autobiography, with a preface by Eric Walter White (London: Calder and Boyars, 1975) ISBN 978-0-7145-1063-7, 0-7145-1082-3. Reprinted again as An Autobiography (1903–1934) (London: Boyars, 1990) ISBN 978-0-7145-1063-7, 0-7145-1082-3. Also published as Igor Stravinsky – An Autobiography (New York: M. & J. Steuer, 1958), and An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton. 1962. ISBN 978-0-393-00161-7.

- — (1947). Poetics of Music in the Form of Six Lessons: The Charles Eliot Norton Lectures for 1939–1940. Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674678569. OCLC 155726113.

- —; Craft, Robert (1959). Conversations with Igor Stravinsky. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 896750. Reprinted Berkeley: University of California Press, 1980. ISBN 978-0-520-04040-3.

- —; — (1960). Memories and Commentaries. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. ISBN 9780520044029. Reprinted 1981, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

- —; — (1962). Expositions and Developments. London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 9780520044036. Reprinted, Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1981.

- —; — (1963). Dialogues and a Diary. Garden City, New York: Doubleday. OCLC 896750. The 1968 reprinted Dialogues varies from the 1963 original, London: Faber and Faber. ISBN 0-571-10043-0.

- —; — (1966). Themes and Episodes. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- —; — (1969). Retrospectives and Conclusions. New York: A. A. Knopf.

- —; — (1972). Themes and Conclusions. London: Faber and Faber. A one-volume edition of Themes and Episodes (1966) and Retrospectives and Conclusions (1969) as revised by Igor Stravinsky in 1971. ISBN 978-0-571-08308-4.

Articles[edit]

- Stravinsky, Igor (29 May 1913). Canudo, Ricciotto (ed.). "Ce que j'ai voulu exprimer dans "Le sacre du printemps"" [What I Wanted to Express in The Rite of Spring]. Montjoie! (in French). No. 2. At DICTECO

- —— (15 May 1921). "Les Espagnols aux Ballets Russes" [The Spaniards at the Ballets Russes]. Comœdia (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (18 October 1921). "The Genius of Tchaikovsky". The Times (Open Letter to Letter to Diaghilev). London.

- —— (18 May 1922). "Une lettre de Stravinsky sur Tchaikovsky" [A Letter from Stravinsky on Tchaikovsky]. Le Figaro (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (1924). "Some Ideas about my Octuor". The Arts. Brooklyn. At SCRIBD.

- —— (1927). "Avertissement... a Warning". The Dominant. London.

- —— (29 April 1934). "Igor Strawinsky nous parle de 'Perséphone'" [Igor Stravinsky tells us about Persephone]. Excelsior (in French). At DICTECO

- —— (15 December 1935). "Quelques confidences sur la musique" [Some secrets about music]. Conferencia (in French). Paris. At DICTECO

- ——; Nouvel, Walter (1935–1936). Chroniques de ma vie (in French). Paris: Denoël & Steele. OCLC 250259515. Translated in English, 1936, as An Autobiography.

- —— (28 January 1936). "Ma candidature à l'Institut" [My application to the Institute]. Jour (in French). Paris.

- —— (1940). Pushkin: Poetry and Music. OCLC 1175989080.

- ——; Nouvel, Walter (1953). "The Diaghilev I Knew". The Atlantic Monthly. pp. 33–36.

Possible sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Craft, Robert (1992). Stravinsky: Glimpses of a Life. London: Lime Tree. ISBN 978-0-413-45461-4.

- Craft, Robert (1994). Stravinsky: Chronicle of a Friendship. Nashville: Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-1285-7.

- Cross, Jonathan (1998). The Stravinsky Legacy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-56365-9.

- Joseph, Charles M. (2001). Stravinsky Inside Out. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-12936-6.

- Libman, Lillian (1972). And Music at the Close: Stravinsky's Last Years (1st ed.). New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02113-4.

- Walsh, Stephen (1988). The Music of Stravinsky. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-816375-6.

- Walsh, Stephen (2006). Stravinsky: The Second Exile: France and America, 1934-1971. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25615-6.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1968). Dialogues. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04650-4.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1972). Themes and Conclusions. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04652-8. (This is a one-volume edition of Themes and Episodes (1966) and Retrospectives and Conclusions (1969) that Stravinsky revised and compiled, so there's no need to use Themes or Retrospectives)

Articles[edit]

- Browne, Andrew J. (October 1930). "Aspects of Stravinsky's Work". Music & Letters. 11 (4). Oxford University Press: 360–366. doi:10.1093/ml/XI.4.360. ISSN 0027-4224. JSTOR 726868.

- Henahan, Donal (7 April 1971). "Igor Stravinsky, the Composer, Dead at 88". The New York Times. p. 1. Archived from the original on 28 September 2022. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

Actual references[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Pronunciation: /strəˈvɪnski/; Russian: Игорь Фёдорович Стравинский, IPA: [ˈiɡərʲ ˈfʲɵdərəvʲɪtɕ strɐˈvʲinskʲɪj] ⓘ

- ^ In his 1936 autobiography, Stravinsky described his admiration for Rimsky-Korsakov and Alexander Glazunov, both leading figures of Russian music at the time: "I was specially drawn to [Rimsky-Korsakov] by his melodic and harmonic inspiration, which then seemed to me full of freshness; to [Glazunov] by his feeling for symphonic form; and to both by their scholarly workmanship. I need hardly stress how much I longed to attain this ideal of perfection in which I really saw the highest degree of art; and with all the feeble means at my disposal I assiduously strove to imitate them in my attempts at composition."[23][24]

- ^ The Symphony in E-flat was designated opus 1, though Stravinsky's inconsistent use of opus numbers makes them futile.[28][29]

- ^ After the premiere of Stravinsky's The Rite of Spring in 1913, Debussy expressed misgivings about the young composer. Saint-John Perse, who attended rehearsals of The Rite with Debussy, later told Stravinsky that the French composer was initially excited about the work but that "he changed when he understood that with it you you had taken the attention of the new generation away from him". Though Debussy continued to insult Stravinsky with others, he never expressed this to the man himself, and a year after Debussy's death, Stravinsky discovered that the third movement of Debussy's En blanc et noir was dedicated to him.[55]

- ^ See "Sacrificial Dance" from The Rite of Spring (audio, animated score) on YouTube, Boston Symphony Orchestra, Michael Tilson Thomas conducting (1972)

- ^ In early 1913, Stravinsky and Ravel collaborated on a completion of Mussorgsky's unfinished opera Khovanshchina as commissioned by Diaghilev, but Stravinsky's illness prevented him from attending the premiered. Later in life, Stravinsky criticized the arrangement, writing that he was opposed to rearranging to work of another artist, especially one of such prestige as Mussorgsky.[66]

- ^ The subsequent Russian revolution in 1917 made it dangerous for Stravinsky to return to Russia, and he never did except for a brief visit in 1962.[71]

- ^ The complications that arose from traveling with de Bosset drove Stravinsky to request visas "for me and my secretary, Mme Vera Sudeikina" in 1924. The two grew so close that in 1929, Stravinsky told his publisher to give de Bosset the manuscript for one of his works, as she was returning to his home soon after.[83]

- ^ Les noces was the last work Stravinsky ever wrote for the Ballets Russes, likely to due a disassociation from stage music onset by Stravinsky's religious crisis.[90]

- ^ Though, some critics found it to be a turning point in Stravinsky's neoclassical music, describing it as a pure work that blended neoclassical ideas with modern methods.[100]

- ^ Stravinsky later looked back on their friendship with happiness, recalling in his autobiography, "He was genuinely attracted by what I was then writing, and it gave him real pleasure to produce my work... These feelings of his, and the zeal which characterized them, naturally evoked in me a reciprocal sense of gratitude, deep attachment, and admiration for his sensitive comprehension, his ardent enthusiasm, and the indomitable fire with which he put things into practice."[109][110]

- ^ The Stravinsky-Gide collaboration was apparently tense: Gide disliked how the music did not follow typical French prosody of his poem and did not attend any rehearsals, and Stravinsky ignored many of Gide's ideas.[119][100]

- ^ See: "Table I: Folk and Popular Tunes in Petrushka" Taruskin (1996, pp. I: 696–697).

- ^ The names of uncredited collaborators are given in Walsh 2001.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 3.

- ^ Walsh 2001.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 6.

- ^ a b c Walsh 2001, 1. Background and early years, 1882–1905..

- ^ a b c White 1979, p. 19.

- ^ Walsh 1999, 6–7.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 17.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 19.

- ^ White 1997, p. 13.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 20–21.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 17.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 25.

- ^ a b Walsh 1999, p. 24.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 21–22.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 5.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 5–6.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 27–29.

- ^ Dubal 2003, p. 564.

- ^ White 1979, p. 24.

- ^ Dubal 2003, p. 565.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 27.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Walsh 2001, 2. Towards 'The Firebird', 1902–09..

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 11.

- ^ White 1997, p. 14.

- ^ White 1997, p. 15.

- ^ White 1979, p. 26.

- ^ a b White 1997, p. 16.

- ^ a b White 1997, p. 18.

- ^ White 1979, p. 192.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 20.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 43.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 43–44, 47, 56.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 45.

- ^ Strawinsky & Strawinsky 2004, p. 64.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 88.

- ^ White 1979, p. 29.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 58–59.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 114.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 59.

- ^ Bowlt 2020, pp. 61–62.

- ^ a b c White 1979, p. 32.

- ^ Garafola 1989, p. 26.

- ^ Bowlt 2020, pp. 65–66.

- ^ White 1997, p. 23.

- ^ Walsh 1999, pp. 122, 126.

- ^ White 1979, p. 32–33.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. 556.

- ^ Caddy 2020, p. 79.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 556–559.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, pp. 574–576.

- ^ a b White 1997, p. 24.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 135.

- ^ a b c d White 1979, p. 35.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 143.

- ^ White 1979, p. 72–73.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 30.

- ^ a b c Stravinsky 1936, p. 31.

- ^ Walsh 1999, p. 148.

- ^ White 1979, p. 36.

- ^ White 1997, p. 35.

- ^ White 1979, p. 34–35.

- ^ a b c Walsh 2001, 3. The early Diaghilev ballets, 1910–14..

- ^ White 1997, p. 38.

- ^ White 1997, p. 40–41.

- ^ White 1997, p. 42–43.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 544–545.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 50.

- ^ White 1979, p. 47.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 111, 115.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 119–120.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 145–146.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 132, 136.

- ^ White 1979, p. 49–50.

- ^ a b c d Walsh 2001, 4. Exile in Switzerland, 1914–20..

- ^ a b c White 1979, p. 51.

- ^ White 1979, p. 54.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 137–138.

- ^ White 1979, p. 56.

- ^ White 1979, p. 61–62.

- ^ White 1979, p. 71–72.

- ^ a b V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 210.

- ^ a b c White & Noble 1980, p. 253.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 211.

- ^ a b c d e Walsh 2001, 5. France: the beginnings of neo-classicism, 1920–25.

- ^ Lawson 1986, p. 291.

- ^ a b Lawson 1986, p. 295.

- ^ Lawson 1986, p. 293–294.

- ^ White 1997, p. 103.

- ^ White 1979, p. 79.

- ^ a b White 1979, p. 85.

- ^ White 1979, p. 82.

- ^ White 1997, p. 75.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, pp. 158–159.

- ^ White 1979, p. 86.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 252.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 85, 89.

- ^ Copeland 1982, p. 565.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. 1618.

- ^ White 1979, p. 90.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Walsh 2001, 6. Return to the theatre, 1925–34. Cite error: The named reference "FOOTNOTEWalsh20016. Return to the theatre, 1925–34" was defined multiple times with different content (see the help page).

- ^ White 1997, p. 120.

- ^ White 1979, p. 90–91.

- ^ White 1997, p. 117.

- ^ White 1979, p. 91.

- ^ White 1997, p. 122.

- ^ White 1997, p. 128–130.

- ^ White 1997, p. 130.

- ^ White 1979, p. 94.

- ^ White 1979, p. 96.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, pp. 154–155.

- ^ White 1997, p. 131–132.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, p. 157.

- ^ White 1979, p. 98.

- ^ White 1997, p. 136.

- ^ White 1997, p. 138–139.

- ^ White 1997, p. 139.

- ^ White 1979, p. 100, 103.

- ^ White 1997, p. 142.

- ^ White 1979, p. 105–106.

- ^ White 1979, p. 105.

- ^ a b V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 340.

- ^ a b White 1979, p. 107.

- ^ White 1997, p. 150.

- ^ a b c Walsh 2001, 7. Last years in France: towards America, 1934–9.

- ^ White 1979, p. 109.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 331.

- ^ White 1997, p. 154–155.

- ^ White 1979, p. 404.

- ^ White 1979, p. 113.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 342.

- ^ a b c White & Noble 1980, p. 240.

- ^ a b c d Walsh 2003, p. 10.

- ^ a b c White & Noble 1980, p. 248.

- ^ Walsh 2003, p. 1.

- ^ a b c White & Noble 1980, p. 259.

- ^ a b Straus 2001, p. 4.

- ^ Walsh 2003, pp. 3–4.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 100.

- ^ Walsh 2003, p. 4.

- ^ White 1979, p. 9.

- ^ a b White 1979, p. 10.

- ^ Walsh 2003, p. 5.

- ^ White 1979, p. 12.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 15–16.

- ^ McFarland 1994, pp. 205, 219.

- ^ McFarland 1994, p. 209.

- ^ McFarland 1994, p. 219 quoting Stravinsky & Craft 1962, p. 128.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 662.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 35–36.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. I: 698.

- ^ a b White 1957, p. 61.

- ^ Hill 2000, p. 86.

- ^ Hill 2000, p. 63.

- ^ Ross 2008, p. 75.

- ^ Grout & Palisca 1981, p. 713.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 149.

- ^ White 1979, p. 563.

- ^ White & Noble 1980, p. 249.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 145.

- ^ a b White 1979, p. 240.

- ^ Walsh 2003, p. 16.

- ^ a b White & Noble 1980, p. 250.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 144.

- ^ a b Keller 2011, p. 456.

- ^ Zak 1985, p. 105.

- ^ Walsh 2001, 4. Exile in Switzerland, 1914–20.

- ^ White 1979, p. 62.

- ^ V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 183.

- ^ a b White & Noble 1980, p. 251.

- ^ Freed 1981.

- ^ a b V. Stravinsky & Craft 1978, p. 218.

- ^ White 1979, p. 92.

- ^ Lowe 2016.

- ^ Taruskin 1992a, pp. 651–652.

- ^ a b Szabo 2011, pp. 19–22.

- ^ Szabo 2011, p. 39.

- ^ Szabo 2011, p. 23.

- ^ Szabo 2011, p. 1.

- ^ White & Noble 1980, p. 256.

- ^ Taruskin 1992b, pp. 1222–1223.

- ^ White & Noble 1980, p. 257.

- ^ Taruskin 1992b, p. 1220.

- ^ Craft 1982.

- ^ a b c d e White & Noble 1980, p. 261.

- ^ Straus 1999, p. 67.

- ^ White & Noble 1980, pp. 261–262.

- ^ White 1979, p. 539.

- ^ White 1979, p. 134.

- ^ White 1979, p. 560, 561.

- ^ Nandlal 2017, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1959, p. 117.

- ^ Nandlal 2017, pp. 84.

- ^ Nandlal 2017, pp. 81.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1959, pp. 116–117.

- ^ a b Predota 2021b.

- ^ Taruskin 1980, pp. 501.

- ^ Taruskin 1996, p. 558, 559.

- ^ Zak 1985, p. 103.

- ^ Taruskin 1980, pp. 502.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 89, 90.

- ^ a b Steinberg 2005, p. 270.

- ^ White 1979, p. 359, 360.

- ^ Steinberg 2005, p. 268.

- ^ Zinar 1978, pp. 177.

- ^ White 1979, p. 375.

- ^ White 1979, p. 376, 377.

- ^ White 1979, p. 451, 452.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1960, p. 146.

- ^ Holland 2001.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 477.

- ^ Stravinsky 1936, pp. 91–92.

- ^ Stravinsky & Craft 1959.

- ^ White 1979, pp. 621–624.

- ^ Walsh 2001, "Writings".

Sources[edit]

Books[edit]

- Bowlt, John E. (2020). "Sergei Diaghilev and Stravinsky: From World of Art to Ballets Russes". In Griffiths, Graham (ed.). Stravinsky in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 61–70. doi:10.1017/9781108381086.010. ISBN 978-1-108-38108-6. S2CID 229417098.

- Caddy, Davinia (2020). "Paris and the Belle Époque". In Griffiths, Graham (ed.). Stravinsky in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. pp. 71–79. doi:10.1017/9781108381086.011. ISBN 978-1-108-38108-6. S2CID 229424313.

- Dubal, David (2003). The Essential Canon of Classical Music. New York: North Point Press. ISBN 978-0-86547-664-6.

- Garafola, Lynn (1989). Diaghilev's Ballets Russes. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-306-80878-4.

- Grout, Donald Jay; Palisca, Claude V. (1981). A History of Western Music (3rd ed.). London and Melbourne: J. M. Dent & Sons. ISBN 978-0-460-04546-9.

- Hill, Peter (2000). Stravinsky: The Rite of Spring. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62714-6.

- Keller, James M. (2011). Chamber Music: A Listener's Guide. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-020639-0.

- Lawson, Rex (1986). "Stravinsky and the Pianola". In Pasler, Jan (ed.). Confronting Stravinsky: Man, Musician, and Modernist. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-05403-5.

- Ross, Alex (2008). The Rest Is Noise. London: Fourth Estate. ISBN 978-1-84115-475-6.

- Straus, Joseph N. (2001). Stravinsky's Late Music. Cambridge Studies in Music Theory and Analysis 16. New York: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-80220-8.

- Taruskin, Richard (1992a). "Oepidus rex". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Vol. 3. New York: Macmillian Press. pp. 650–652. ISBN 978-0-935859-92-8.

- Taruskin, Richard (1992b). "The Rake's Progress". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Opera. Vol. 3. New York: Macmillian Press. pp. 1220–1223. ISBN 978-0-935859-92-8.

- Taruskin, Richard (1996). Stravinsky and the Russian Traditions: A Biography of the Works Through Mavra. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-07099-8.

- Walsh, Stephen (1999). Stravinsky: A Creative Spring: Russia and France, 1882-1934. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-22749-1.

- Walsh, Stephen (20 January 2001). "Stravinsky, Igor". Oxford Music Online. Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/gmo/9781561592630.article.52818.

- Walsh, Stephen (2003). The New Grove Stravinsky. London: Macmillian Publishers. ISBN 978-0-333-80409-4.

- White, Eric Walter (1957). "Stravinsky". In Hartog, Howard (ed.). European Music in the Twentieth Century. London: Pelican Books.

- White, Eric Walter (1979). Stravinsky, The Composer and his Works (2nd ed.). Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-03983-4.

- White, Eric Walter (1997). Stravinsky: A Critical Survey, 1882–1946. Mineola: Dover Publications. ISBN 978-0-486-29755-2.

- White, Eric Walter; Noble, Jeremy (1980). "Stravinsky, Igor". In Sadie, Stanley (ed.). The New Grove Dictionary of Music and Musicians. Vol. 18. London: Macmillan Publishers. pp. 240–265. ISBN 978-0-333-23111-1.

- Stravinsky, Igor (1936). An Autobiography. New York: W. W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-00161-7.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1959). Conversations with Igor Stravinsky (1st ed.). Garden City: Doubleday. ISBN 978-0-571-11464-1.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1960). Memories and Commentaries. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04402-9.

- Stravinsky, Igor; Craft, Robert (1962). Expositions and Developments. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-04403-6.

- Stravinsky, Vera; Craft, Robert (1978). Stravinsky in Pictures and Documents. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-24382-1.

- Strawinsky, Théodore; Strawinsky, Denise (2004). Wenborn, Neil (ed.). Catherine and Igor Stravinsky: A Family Chronicle. Translated by Walsh, Stephen. New York: Schirmer Trade Books. ISBN 0-8256-7290-2.

Articles[edit]

- Copeland, Robert M. (1982). "The Christian Message of Igor Stravinsky". The Musical Quarterly. 68 (4): 563–579. doi:10.1093/mq/LXVIII.4.563. ISSN 0027-4631. JSTOR 742158.

- Craft, Robert (December 1982). "Assisting Stravinsky – On a misunderstood collaboration". The Atlantic. pp. 64–74. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Freed, Richard (26 July 1981). "The Pergolesi Puzzle". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on 27 August 2017. Retrieved 13 April 2023.

- Holland, Bernard (11 March 2001). "Stravinsky, a Rare Bird Amid the Palms; A Composer in California, At Ease if Not at Home". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 24 March 2023. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- Lowe, Dominic (27 September 2016). "'Sing O Muse': Salonen explores Stravinsky inspired by Greek myth". Bachtrack. Retrieved 6 April 2023.

- McFarland, Mark (1994). ""Leit-harmony", or Stravinsky's Musical Characterization in "The Firebird"". International Journal of Musicology. 3. Peter Lang: 203–233. ISSN 0941-9535. JSTOR 24618812.

- Nandlal, Carina (22 May 2017). "Picasso and Stravinsky: Notes on the Road from Friendship to Collaboration". Colloquy (22). Monash University: 81–88. doi:10.4225/03/5922784a722cd.

- Predota, Georg (17 March 2021). "Stravinsky's Literary Sources". Interlude. Retrieved 23 June 2023.

- Steinberg, Michael (22 April 2005). "Stravinsky: Mass". Choral Masterworks: A Listener's Guide. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 269–273. ISBN 978-0-19-802921-2.

- Straus, Joseph N. (April 1999). "Stravinsky's "Construction of Twelve Verticals": An Aspect of Harmony in the Serial Music". Music Theory Spectrum. 21 (1): 43–73. doi:10.2307/745920. JSTOR 745920.

- Szabo, Kyle (2011). The evolution of style in the neoclassical works of Stravinsky (Dissertation thesis). James Madison University. Retrieved 4 April 2023.

- Taruskin, Richard (Autumn 1980). "Russian Folk Melodies in The Rite of Spring". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 33 (3). University of California Press: 501–543. doi:10.2307/831304. ISSN 0003-0139. JSTOR 831304.

- Zak, Rose A. (1985). "'L'Histoire du soldat': Approaching the Musical Text". Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal. 18 (4): 101–107. ISSN 0027-1276. JSTOR 24778812.

- Zinar, Ruth (Fall 1978). "Stravinsky and His Latin Texts". College Music Symposium. 18 (2). College Music Society: 176–188. ISSN 0069-5696. JSTOR 40373983.