User:Mdd/Daniel McCallum quotes

| This is not a Wikipedia article: It is an individual user's work-in-progress page, and may be incomplete and/or unreliable. For guidance on developing this draft, see Wikipedia:So you made a userspace draft. Find sources: Google (books · news · scholar · free images · WP refs) · FENS · JSTOR · TWL |

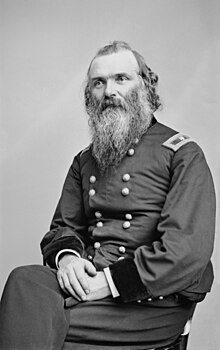

Daniel Craig McCallum (21 January 1815 – 27 December 1878) was a railroad engineer, general manager of the New York and Erie Railroad and Union Major General during the American Civil War, known as one of early pioneers of management. He set down a set of general principles of management, and is credited for having developed the first modern organizational chart.

Quotes about McCallum[edit]

Edward Harold Mott Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie1899[edit]

Source: Edward Harold Mott Between the Ocean and the Lakes: The Story of Erie. Collins, 1899. (online)

Biography, p. 434[edit]

- Daniel Craig McCallum was born at Renfrewshire, Scotland, in 1814. His father, Peter McCallum, who was a tailor, emigrated to this country in 1822, and settled in Rochester, NY. Not liking his father's trade, he left home with his entire wardrobe tied up in a handkerchief. He walked his way to Lundy's Lane, where he apprenticed himself to learn the trade of carpenter. He became a skilful architect, designing St. Joseph's Church, Odd Fellows Hall, the Mansion House Block, the Waverly Hotel, the House of Refuge, and other prominent buildings in Rochester. He developed a strong taste for mechanical engineering, and made rapid strides in his profession. He invented an inflexible arch truss for bridges, the use of which on various railroads brought him later an income of $75,000 a year.

- He entered the employ of the New York and Erie Railroad Company in 1848, and was appointed superintendent of the Susquehanna Division in October, 1852. As stated above, he was made general superintendent in May, 1854. February 25, 1857, he tendered his resignation, because "a respectable number" of the Directors differed with him in regard to " the discipline that had been pursued in the superintendence of the operations of the road." The resignation was accepted, but the Board of Directors gave him a letter of regret at parting with him, and President Ramsdell addressed him a long personal letter, assuring him, in substance, that he was not one of the number in the management that did not approve of his discipline.

- Ex-Superintendent McCallum devoted himself to his private business until 1862, when, February 1st of that year, he was appointed by Secretary Stanton military director and superintendent of the military railroads of the United States, with authority to take possession of all railroads and rolling stock that might be required for the transportation of troops, arms, military supplies, etc. He ranked as a colonel. He found only one railroad in possession of the Government— the one running from Washington to Alexandria. He speedily changed the state of affairs. His work in establishing the network of railroads that forwarded so materially the efforts of McClellan, Burnside, Hooker, Meade, and Grant, respectively, in the Peninsular campaign, at Fredericksburg, Chancellorsville, Gettysburg, and other fields, belongs to the history of the Civil War, where it is amply recorded. During his memorable work of hurrying troops forward to the rescue of 1¡rant when he was cornered at Chancellorsville, he placed Gen. Carl Schurz, under arrest for officious meddling with his plans. McCallum saved 1irant at Chancellorsville, and was made a Brigadier-General by Stanton as a reward for his services on that occasion. General McCallum built 2,105 miles of new railroad and twenty-six bridges, and rebuilt 64013 miles of old railroad, to meet the necessities of the Union army during the war, besides confiscating and opening to the service of the Northern generals the great network of old railroads without which our armies would have been powerless against the enemy. He expended $42,000,000 of the Government money in his work, and accounted for every cent of it.

- After the war, in 1865, he retired to private life, making his home at Glen Mary, at Owego, a place made famous by Nathaniel P. Willis, who lived there at one time, and where he built an elegant residence.

- General McCallum was a poet of no mean order, one of his poems being "The Water Mill," known everywhere as a perennially popular one, the rendering of the refrain of which, "The mill will never grind again with the water that is past," has brought fame and dollars to many an elocutionist. When the Atlantic and Great Western Railroad was building he became consulting engineer. He subsequently removed to Brooklyn, where he died, December 27, 1878. The introduction of iron bridges had relegated his wooden truss bridge to practical uselessness in railroad construction, and his income from that source had been reduced to a small amount during the later years of his life, and he left but a modest fortune to his family, which consisted of four sons and two daughters.

About his promotion to Superintendent in 1854 and his resignation in 1857[edit]

- Charles Minot, who had come in as General Superintendent of the railroad in 1850, was called upon by the Directors in May, 1854, to put in force a code of rules for the government of employees which had been drafted by D. C. McCallum, then Superintendent of the Susquehanna Division. Superintendent Minot read the rules, and reported that he could not approve of all of them, as they were not capable of application to the successful operation of the railroad. The Directors informed him that the rules must be adopted and enforced. Superintendent Minot, at any rate, was not in favor with the ruling influences in the Board, Homer Ramsdell and Daniel Drew, although he was exceedingly popular with the employees and along the line of the railroad, he having more than once protested against the discriminations of the Board against Goshen and other towns in the running of trains and the arrangement of freight charges. Minot refused to enforce the new rules and resigned, and was succeeded by D. C. McCallum, who inaugurated a system of management so strict, and demanding such discipline among employees, that it soon gave rise to discontent and open acts of revolt, especially among engineers and firemen. The first trouble with employees the Company had ever had came about in June, 1854, only one month McCallum became Superintendent. The engineers objected to two of his rules, went on strike, and gained their point, after traffic had been practically suspended for ten days.

- The summer of 1854 was one of great business depression. Banks were cautious in extending accommodation, and individuals or corporations that had obligations the maturity of which was imminent, and which could not be met except by the obtaining of temporary loans, had a dismal future. It was known in August of 1854 that the New York and Erie Railroad Company was in a situation such as that...

- p. 115

- The year of 1855 was one of short crops throughout the country, and one not of general activity in the commercial affairs, but the New York and Erie Railroad earned §833,418.87 more than its working expenses and interest on its funded and floating debt, or 8 1/3 per cent, on its capital stock. This surplus was used for improvements. The notable event in the history of the railroad during 1856 was the great strike of the engineers, the second on the road. Like its predecessor of 1854, it was caused by opposition to the severe rules of General Superintendent McCallum. This strike began in October, after the end of the fiscal year, and the disastrous effect it had on the railroad's business did not appear in the Directors' report for that year, which showed net earnings to September 30th of $1,246.712. The sinking fund absorbed §420,000 of this, all except §120.000 of the balance was expended for new railroads, improvements, and lake steamboats. Work on the terminal facilities at Jersey City was begun in 1856....

- p. 119

- Early in June the Company's statement of the business of the road for the six months ending March, 31, 1857, was made. It showed that the expenses, not including the §210,000 paid into the sinking fund during that period, had exceeded the earnings by more than $72,000. The decreased business due to the engineers' strike and the extraordinary cost of that strike, and to the losses by snow blockades and floods during the winter, was given in explanation of this discouraging showing. The most marked falling off in traffic reported was in freight, and the chief increase of expenses declared to be in repair of cars and engines.

- Superintendent McCallum had been forced to resign in March, 1857. The engineers' strike had cost the Company upward of §500,000, and left the road in wretched condition. After the resignation of McCallum the railroad, by order of the Board, March 12, 1857, was reduced from four divisions to two. One, from New York to Susquehanna, with the branches, were placed in charge of Hugh Riddle. Of the other, from Susquehanna to Dunkirk, J. A. Hart was made Superintendent. President Ramsdell acted also in the capacity of General Manager of operations.

- p. 120

About McCallum's bridge design[edit]

- At the time of the construction of the Erie, the building of railroad bridges was in its infancy, or experimental stage. The bridges were all of wood. The design first in use was the Bunn, the bridges being covered. Later the Company adopted the Fowler and the McCallum. In constructing a bridge of either of the two latter designs, a level platform as long as the bridge, and at least twenty-five feet wide, was erected, on which the whole broadside of the bridge was drafted. Then the outside posts of the bridge, after having been framed for the chords and arches, were put in place and firmly fastened ; the braces were framed and fitted in position ; the chords and arches (there was an arch to each span of the bridge), were placed in position, and the top posts and braces were framed and similarly placed. Thus a whole broadside of the bridge was completed. This had to be all taken apart and piled by itself, and the other broadside constructed in the same way. The building of a large bridge of this kind made a long, heavy job, requiring the handling of several thousand tons of timber at least seven times over, besides the work of framing.

- p. 348

About telegraphy, the application at Ernie and McCallum's role[edit]

- Henry O'Reilly, one of the pioneers of telegraphy in this country, wrote as follows, under date of July 17, 1852:

- Though railway telegraphing is attempted to a very limited extent, even the partial experiment on one of the most profitable railroads in America (although that experiment employed little of the organized system here proposed) will probably fully sustain the assertion which I hazarded when commencing the establishment of the telegraph system by individual enterprise seven years ago, that a well-arranged telegraph for railroad purposes would, each and every year, render to a railroad company sufficient benefits to counterbalance the whole cost of construction.

- He dwelt upon the feasibility of telegraph messages in the operating of railroads, instancing that signals could be given from any point at any time of night or day to alarm and inform any and all stations, along the whole extent of the line, of delays, accidents, or other matter essential to safety of passengers and property. Not only every station, but every train while in motion, he declared, could be signalled and cautioned whenever necessary, by the ringing of bells by electricity, or displaying signals along the line on posts between stations, to warn engineers and conductors of any difficulty or irregularity which might result in mishap.

- These suggestions were placed before the New York Legislature in 1853, the Legislature having, in 1852, discussed the subject of the seemingly undue prevalence of railroad accidents, and propounded to the railroad companies of the State a number of questions in relation to the matter, for official answer. The Erie made no reply to any of the questions.

- If it had, there might have been a record of the date on which the experiment by Superintendent Charles Minot of running a train by telegraphic order was tried - which experiment proving successful, the system was regularly adopted by the Company, and it became, as to-day, universal on railroads. As it is, there is no such record. The late William H. Stewart, the Erie conductor who ran the train thus first moved under telegraphic instructions, did not remember with certainty the year or the month. He thought it was in the fall of 1852 ; but as Mr. O'Reilly, in his deliverance to the Legislature in July, 1852, mentions the fact that railroad telegraphing was then in use "on one of the most profitable railroads in America," meaning the Erie, the first telegraphic train order must have been given before the time mentioned by Mr. Stewart, probably in the fall of 1851. At any rate, the use of the telegraph as an invaluable adjunct of railroad operation was suggested, if not advocated, by Mr. O'Reilly at least six years before it had practical demonstration on the Erie at the hands of Superintendent Minot.

- But years before the telegraph was used for any purpose in this country, not to mention its application to railroad operation, the Cooke and Wheatstone "magnetic telegraph" had been in use upon several English railroads, and Superintendent McCallum 's declaration, made in 1855, that a single track railroad with a telegraph connection was much superior to a double track railroad without such connection, was anticipated as early as 1836, when the editor of The New York Railroad Journal, referring to the Cooke and Wheatstone telegraph, wrote in his periodical that "a single track of railroad of any length can be made as effective and as safe by means of this auxiliary as any double track can be, and this, too, at an original outlay of about the sum required to keep annually a track in repair. The advantages to railroads of this important invention can easily be understood by those familiar with railroad management, and if to these we add the profit to be derived from the transmission of intelligence, we certainly think there is ample inducement for its employment upon every railroad in the United States."

- p. 416-417

- The novelty and importance of applying the telegraph to the running of its trains by the Erie did not begin to attract general attention until 1855. In his report for that year, John T. Clark, New York State Engineer, referred to this innovation at length. As his statements describe accurately the system of operation on the Erie that had gradually developed under the telegraphic adjunct, and which, modified and improved by Superintendent Minot and his successor, D. C. McCallum, eventually became the standard system on railroads everywhere, they are reproduced here as interesting and valuable historic data:

- The telegraph has been in use on the Erie since 1852 [meaning practically]. By the concurrent testimony of the superintendents of the road, it has saved more than it cost every year. There is an operator at every station on the line, and at the important ones day and night, so placed that they have a fair view of the track. They are required to note the exact time of the arrival, departure, or passage of every train, and to transmit the same by telegraph to the proper officer. On each division there is an officer called train despatcher, whose duty it is to keep constantly before him a memorandum of the position of every train upon his division, as ascertained by the telegraphic reports from the several stations. The trains are run upon this road by printed time-tables and regulations. When they become disarranged, the telegraph is also used to disentangle and move them forward. When trains upon any part of this road are delayed, the fact is immediately communicated to the nearest station, and from there by telegraph to every station on the road. Approaching trains are thus warned of the danger, and accidents from this cause are prevented.

When one or more of the trains from any general cause, like that of snow storms, etc., have been retarded and are likely to produce delays on the other trains, the train despatcher is authorized to move them forward by telegraph under certain rules which have been arranged for that purpose. Having before him a schedule of the time of the passage of each train at its last station, he can determine its position at any desired moment with sufficient accuracy for his present purpose, and can adopt the best means of extricating the delayed trains and of regulating the movement of all so as to avoid any danger of collision or further entanglement. He then telegraphs to such stations as are necessary, giving orders to some trains to lay by for a certain period, or until certain trains have passed, and to others to proceed to certain stations and there await further orders.

To prevent any error or misunderstanding between the despatcher and the conductor of the train, he is required to write his order in the telegraph operator's book. The operator who receives the message is required to write it upon his book, and to fill up two printed copies, one of which he hands to the conductor of the train, and one to the engineman. The despatcher then transmits a message to the conductor, asking him the question : " How do you understand my message?"

To which the conductor must make reply in his own words, repeating the substance of the message as he understands it, to detect any error which may be made by the operator, or of his own understanding of it. If this is satisfactory to the despatcher, he telegraphs, " All right, go ahead ! " and until this final message is received, no trains can be moved on the road by telegraph.

Time is saved by using abbreviations for stations and messages, trains, etc.

In this way, if a passenger train is delayed an hour or more, all freight trains which would be held by it at the several stations under the general rules are moved forward to such other passing places as they are certain to reach before the delayed trains could overtake them, and thus it frequently happens that in a single day the trains which would otherwise be delayed, are moved forward by telegraph, the equivalent to the use of two or three engines and trains.

- The telegraph has been in use on the Erie since 1852 [meaning practically]. By the concurrent testimony of the superintendents of the road, it has saved more than it cost every year. There is an operator at every station on the line, and at the important ones day and night, so placed that they have a fair view of the track. They are required to note the exact time of the arrival, departure, or passage of every train, and to transmit the same by telegraph to the proper officer. On each division there is an officer called train despatcher, whose duty it is to keep constantly before him a memorandum of the position of every train upon his division, as ascertained by the telegraphic reports from the several stations. The trains are run upon this road by printed time-tables and regulations. When they become disarranged, the telegraph is also used to disentangle and move them forward. When trains upon any part of this road are delayed, the fact is immediately communicated to the nearest station, and from there by telegraph to every station on the road. Approaching trains are thus warned of the danger, and accidents from this cause are prevented.

- The blank orders that were the basis of telegraphic running of trains originated with Superintendent McCallum, in 1854. They became famous as " Blank 31," " Blank 32," and " Blank A." The use of Blank 31 came under Rule 12 of the McCallum code, which was that "when a meeting place is to be made for trains moving in contrary directions, the right to run shall be made certain, positive, and defined, without regard to time." and this form of order was prescribed:

- From....... Station to......., Conductor, and ....... Engineer : You will run to....... Station regardless of....... train bound (east or west). "31"

- ....... Division Superintendent.

- per ....... Despatcher.

- ....... Division Superintendent.

- Received by ....... Operator

- From....... Station to......., Conductor, and ....... Engineer : You will run to....... Station regardless of....... train bound (east or west). "31"

- The figures “ 31 " meant, “ How do you understand? ” The conductor and engineer to whom such a despatch was addressed were under obligation, by the rules, to reply to it at once, and in doing so would telegraph : "32," which meant, " I understand that I am to ," and then a repetition of the order followed. "Blank A" was an order of those charge of trains never cared to be under the necessity of receiving...

- p. 421

- Further comment

Part of this section copy/pasted in Charles Minot (railroad executive)#The telegraph system at Erie

More about his work as Superintendent[edit]

- McCALLUM AND THE BAGGAGE SMASHERS.

D. C. McCallum was general superintendent of the New York and Erie Railroad in 1856. According to the local papers of that day, the "baggage smasher" was even then a terror to the travelling public, and Superintendent McCallum had the temerity to issue an order that employees of the Company must handle the baggage of passengers with the utmost care, under pain of instant dismissal if the order was disregarded, travellers being requested to call the attention of the superintendent to any case of "baggage smashing" that came under their notice. Such an order as that to-day would be considered as a good cause for a general indignation of baggage handlers, and as an infringement of their rights, warranting them to strike in a body of demand redress.- p. 424-5

About McCallum's predecessor Charles Minot[edit]

Section moved to Charles Minot (railroad executive) -- Mdd (talk) 19:04, 7 February 2014 (UTC)

About the 1854 strike[edit]

- MEMORABLE AND DISASTROUS STRIKES. 1854.

D. C. McCallum, superintendent of the Susquehanna division, drafted a code of rules regulating the running of trains, which he submitted to the Directors of the Company early in 1854. They were pleased with it, and officially adopted it as supplementary to the existing rules. Charles Minot was then the general superintendent. The McCallum rules were adopted March 6, 1854, and Minot was directed to put them in force. He did not approve of some of them. He refused to promulgate the new code, and resigned.- p. 430

- D. C. McCallum took charge as general superintendent May 1, 1854, and his new rules were at once put in force. Trouble was not long in following. The engineers objected to the new order of things, particularly to Rule 6 of the McCallum code, which declared that every engineer would be held responsible for running off a switch at a station where he stopped, whether he should run off before or after receiving a signal to go forward from a switchman or any other person. The engineer, under this rule, was expected to see for himself whether the switch was right or not, and take no person's authority for the same at stations where trains stopped. The engineer, however, had a right to run past stations where he did not stop at a rate he was willing to hazard on his own account, the Company reserving the right to decide whether such running was reckless or not. " The road must be run safe first and fast afterward," the management declared.

The engineers also protested against the alleged " posting rule " of the Company, under which notices of dismissal of engineers was at once posted with other railroad companies to the injury of the men.

An abrogation of the distasteful rules was requested, June 15th, by a committee, consisting of John Donohue, William Schrier, and John C. Meginnes. Superintendent McCallum's explanation and reply not being satisfactory, the engineers struck on June 17th - the first strike in the history of the railroad. The Company gave notice to all the men that all who returned to work within three days after June 20th would be retained in the Company's employ. All others would be dismissed from the service. So few returned to work, and the Company not being in condition to maintain a struggle with its engineers, and the business of the road being at a standstill, June 24th Superintendent McCallum addressed this letter to the strikers' committee :

- New York and Erie Railroad,

- Office of General Superintendent,

- New York, June 24, 1S54.

- To Joint Donahue, Il'm. Schrier, John C. Meginnes, Committee.

- Gentlemen: I have explained Rule 6, Supplementary Instructions of May 15th, as follows :

- The rule simply means this, that the engineer is responsible for the running off at a switch at a station where his train stops, whether he shall run off before or after receiving a signal to go forward from a switchman or any other person. But no engineer shall be discharged under such circumstances, without a full hearing of the case, or unless it ran be clearly shown that he ran off through his own carelessness.

- By reference to what I called the Posting Rules I would again say that it has not been extended except to the several divisions of this road, in all of which this Company has a financial interest, and that we have no intention of extending it further.

- Respectfully yours,

- D. C. McCallum,

- General Superintendent.

- Respectfully yours,

- To which the committee replied :

- Susquehanna Depot, June 2(11/1.

- D. C. McCallum. Esq., General Superintendent N.Y. & E.R.R.:

- At a meeting of the engineers of the New York and Erie Railroad, held at the United States Hotel, to hear the report of the committee, upon hearing which report and reading the letter of D. C. McCallum, it was unanimously

- Resolved, That the letter of D. C. McCallum. Esq., to this committee, as read before our committee this day, in addition to the verbal statement of Mr. McCallum to the committee, we decide satisfactory.

- Resolved', That we present to our committee our warmest thanks for the constant manner in which they have performed all the arduous duties imposed upon them.

- Resolved, That we make every effort to resume our work.

- Resolved, That the committee immediately inform Mr. McCallum of our action at this meeting.

- John Donohue,

- Wm. Schrier,

- John C. Meginnes,

- It was an easy matter to return to work, and thus the first strike on the Erie was settled after ten days' paralysis of the business of the railroad, and a loss of many thousands of dollars to the Company.

- The engineer over whose case the strike resulted was Benjamin Hafner of the Eastern Division. On the evening of June 10th ran off a switch at Turner's. He was dismissed. After he was dismissed Hafner was sent for by Superintendent McCallum to talk about the incident. Hafner refused to go unless he was reinstated first. McCallum declined to reinstate him without a consultation. The matter was taken up by all the leading engineers on the Delaware and Eastern divisions, with the above result.

- Some of the engineers did not join in the strike, among them Joe Meginnes. W. H. Power was then superintendent of the Delaware Division (division agent, it was then called), and he himself acted as engineer in efforts to run a train over that division, and succeeded in doing so in spite of the strikers, who assembled in crowds at the Port Jervis station, and had compelled every engineer who attempted to go out to dismount from his engine, except Joe Meginnes, who stuck to his engine through it all. He was opposed to strikes on principle.

- p. 431-2

- Comment: Benjamin Hafner later re-entered the employ of the Erie and continued in active service until March, 1892, see American Locomotive Engineers (1908) p. 304 (online) amd here

- Comment: A similar story about the 1854 strike can be found in American Locomotive Engineers (1908), p. 59-60 (online)

- Further comment

Part of the above text is copy/pasted in Benjamin_Hafner#The_1854_strike_at_Erie.

More about the 1856-57 strike[edit]

More about this strike can be found at:

- E.H. Mott. Between the ocean and the lakes (1889/1901). p. 432-343 (online)

- H.R. Romans (ed.) American Locomotive Engineers (1908), p. 59-60 (online)

About the succession at Erie[edit]

- Daniel Craig McCallum. ... May I, 1854 - Mar. 1, 1857

- No successor was appointed to McCallum as general superintendent. President Ramsdell assumed the duties of superintendent, and April 1, 1857. The old system of operating' the railroad by Four divisions was changed to one that divided the railroad into two divisions: one from New York to Susquehanna, called the Eastern Division, and one from Susquehanna to Dunkirk, called the Western Division. Neither the Rochester nor Buffalo Divi inns had as yet come to he parts of the Erie. Hugh Riddle was made superintendent of the Eastern Division, and James A. Hart, of the Western Division. This arrangement was continued under the administration of President Moran, he acting as general superintendent. In August. 1859, Charles Minot, having been recalled to the railroad as general superintendent, the old four-division system was restored.

- p. 480

See also[edit]

- Presidents New York and Erie Railroad

- Eleazar Lord (1833–35), (1839–41), (1844–45) -- Eleazar Lord quotes

- James Gore King (1835–1839)

- James Bowen (1841–1842)

- William Maxwell (1842–1843) -- William Maxwell quotes

- Horatio Allen (1843–1844)

- Benjamin Loder (1845–1853)

- Homer Ramsdell (1853–1857)

- General Superintendents New York and Erie Railroad

- Hezekiah C. Seymour (Sept. 23, 1841 - April 1, 1849) - - - Hezekiah C. Seymour quotes

- James P. Kirkwood (April 1, 1849 - May 1, 1850) - - - James P. Kirkwood quotes

- Charles Minot (May 1, 1850 - May 1, 1854) - - -

- Daniel Craig McCallum (May I, 1854 - Mar. I, 1857) - - - Daniel McCallum quotes --- q:Daniel Craig McCallum