User:IllaZilla/Larry Livermore

Larry Livermore | |

|---|---|

Livermore in Brooklyn, 2015 | |

| Background information | |

| Birth name | Lawrence W. Hayes |

| Also known as | Lawrence Livermore |

| Born | October 28, 1947 Detroit, Michigan |

| Origin | Spy Rock, California |

| Genres | Punk rock |

| Occupation(s) | Singer, guitarist, record producer, record label owner, blogger, author |

| Instrument(s) | Guitar |

| Years active | 1984–present |

| Labels | Lookout |

| Website | larrylivermore |

Lawrence W. Hayes (born October 28, 1947),[1]: 7 known by the pseudonym Lawrence "Larry" Livermore, is an American countercultural figure, author, and blogger, and formerly a columnist, zine publisher, musician, record producer, and owner of Lookout Records, an independent record label which he headed from 1987 to 1997.[2] Under Livermore, Lookout was part of the punk rock revival of the 1990s, releasing records by many bands from San Francisco's East Bay including the first two albums by Green Day.[2] During that decade Livermore "played a key role in developing the autonomous cultural apparatus of the East Bay punk scene and, through his writing and his work as a record producer, in shaping punk rock subculture in the United States and abroad."[2]

Born in Detroit, Livermore immersed himself in the counterculture of the 1960s, joining the hippie movement and eventually moving to the San Francisco Bay Area, where he became interested in the punk movement of the late 1970s.[2] In 1982 he moved to the remote community of Spy Rock in the mountains of Mendocino County, where he launched a self-published magazine titled Lookout! and a punk rock band, the Lookouts, recruiting as his drummer then-preteen Tré Cool, who would later achieve international celebrity as a member of Green Day.[2] Re-inserting himself into the Bay Area punk scene in the mid-1980s, Livermore became a columnist for Maximumrocknroll and contributed to other underground publications and zines.[2] He was one of the earliest organizers and volunteers of the non-profit music venue at 924 Gilman Street in Berkeley.[2] He co-founded Lookout Records with David Hayes in 1987, and the label made a name for itself releasing records by local acts including Operation Ivy and Green Day.[2] After David Hayes left Lookout in 1989, Livermore ran the label out of his Berkeley apartment for the next several years. He also started a new band, the Potatomen, in 1992.[2]

After Green Day signed to major label Reprise Records in 1993 and achieved mainstream international success, Lookout quickly grew into a multi-million dollar business buoyed largely by sales of the band's back catalog as well as that of Operation Ivy, members of which had also gone on to mainstream success with Rancid. Citing discomfort with the label's rapid growth and shifts in musical output, as well as disputes with Ben Weasel of the band Screeching Weasel over royalty payments, Livermore resigned from Lookout in 1997 and moved to London for ten years, then to New York City.[2]

After a public split with Maximumrocknroll in 1994, Livermore wrote for rival zine Punk Planet until it ceased publication in 2007, then for Verbicide from 2008 to 2012.[2] In the 2010s he authored two memoirs about his life and career: Spy Rock Memories (2013) and How to Ru(i)n a Record Label: The Story of Lookout Records (2015).[2]

Early life[edit]

Hayes grew up with his parents and three siblings in Detroit, where his father worked for the United States Postal Service for some 35 years.[3][4]: xiii As a child, Hayes taught himself to read and discovered doo-wop and rock and roll music by listening to the family radio.[4]: xiii [5][6] At age 13 he joined a gang of greasers, with whom he participated in acts of vandalism, robbery, and violence over the next few years.[4]: xiii [7] He attended Cabrini High School, where he became a page editor and columnist for the school newspaper and won a high school journalism award from the The New York Times.[6][8][9] After graduation most of his friends were drafted and sent to the Vietnam War, but according to Hayes, he "[had] already been in enough trouble that the army didn't want me" (in another account, he stated that he and his friends planned to enlist in the Marine Corps, but he got so drunk the night before that he missed going with them to the recruitment office).[4]: xiv [10] He became interested in the Detroit music scene, becoming a fan of the the Supremes, the Motown record label, proto-punk band the MC5, and, a few years later, the Stooges from nearby Ann Arbor.[4]: xiv–xv [11]

In September 1965 he moved to Ypsilanti to attend Eastern Michigan University, but was expelled the following month and started working night shifts at the Motor Wheel factory, making wheel and brake drums for General Motors.[12][13] During the next few years he was expelled from college two more times and failed out another.[14] One of his expulsions was for drinking in the dormitory, another in 1966 was for setting fire to the school in an attempt to burn it down ("I have a history of pyromania", he said of the incident decades later).[15][16][17][18]: 329 He was arrested for arson, but rather than being criminally prosecuted he was placed on Social Security Disability Insurance for mental illness, which both disqualified him from the military draft and provided his main income for the next 20 years.[16][18]: 329

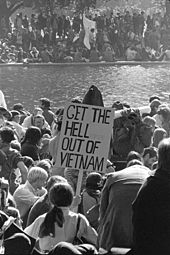

During this time Hayes worked intermittent factory and mill jobs for Ford, Chrysler, and McLouth Steel; joined a new, more violent gang; and was repeatedly arrested and evicted, occasionally homeless, and "drifted further down a rathole of alcohol and crime until 1967, when, while sniffing glue and listening to the Beatles' Revolver album, I had a spiritual experience that turned me overnight into a raving hippie lunatic. I spent the rest of the year living on LSD and cheese sandwiches, shoving flowers in people's faces, and haranguing passersby about world peace."[4]: xv–xvi [13][19] He participated in the April 1967 antiwar demonstrations in New York City organized by the National Mobilization Committee to End the War in Vietnam, as well as the coalition's follow-up "March on the Pentagon" that October: "the one where the hippies promised they were going to levitate the Pentagon", he wrote 40 years later; "Being as high on drugs as I typically was during those days, I never did notice if the building had left the ground, but I did have my first experience – to be repeated many, many times – of being tear-gassed and – hopefully not to be repeated – being charged by troops with fixed bayonets."[20][21]

In February 1968 Hayes was arrested in a sting operation in Ann Arbor during a cannabis transaction, while also in possession of a large amount of LSD.[4]: xv–xvi [22][23] Facing a minimum of 20 years in prison for selling marijuana, he jumped bail and fled, living under a succession of false identities.[4]: xvi [22][23][24][25] He stayed at a friend's parents' house in Flatbush, Brooklyn until the FBI came looking for him, then bounced to Kent and Akron, Ohio, back to New York ("shunting between junkie pads and abandoned buildings on the Lower East Side"), and then to Berkeley, California, where he stayed for the rest of the year.[15][23][24][25][26][27][28] He eventually returned to Michigan when the marijuana laws had relaxed, turned himself in, and was offered a choice between a lengthy prison term and a suspended sentence consisting of a week's jail time and two years' probation, conditioned on holding down a steady job.[4]: xvi [22][23][24][26] Choosing the latter, he wound up working at the Great Lakes Steel mill on Detroit's Zug Island, first breaking rocks in the slag pit, then working at the coke oven producing fuel for the blast furnace and monitoring gauges, but spent most of his time high on LSD or mescaline.[4]: xvi [19] By August 1969 he was working as a janitor at the University of Michigan, and attended the Woodstock festival ("Well, for a little while, anyway", he wrote 40 years later; "Less than 24 hours, actually, since I'd apparently already formed my lifelong habit of arriving late and leaving early when it comes to rock and roll shows, but enough, I think, to get in the proper spirit of things").[14][29]

Move to the Bay Area[edit]

In the early winter of 1969, inspired by a psychedelic experience and an assortment of song lyrics, Hayes left Michigan and moved to California.[4]: xvi–xvii Soon after arriving in San Francisco's East Bay, he was was arrested for amphetamine possession; he was released a few days later, "but only after [the police had] stolen most of my money, leaving me with $35 and a bag of brown rice to start my new life in Berkeley."[4]: xvii There he lived a hippie lifestyle through the early 1970s, occasionally returning to Michigan "when things got too rough or confusing out west, but essentially from then on I was a California boy."[30][31][32]: 12–13 He became a "cadre" member of the Rainbow People's Party (aka the White Panther Party), but left after becoming disillusioned by party leader John Sinclair's hypocritical private use of cocaine, which, along with heroin, Sinclair publicly denounced as a "honky death drug".[4]: 43 [33] Having tried unsuccessfully to break into college journalism during his intermittent tenure at Eastern Michigan University, he began making submissions to underground newspapers; his writings appeared in the East Village Other, Ann Arbor Sun, and Berkeley Barb.[6] In late 1971, destitute and staying in Ann Arbor and Kent, he applied for welfare: "Ironically the shrink that examined me was a hippie revolutionary, who basically said 'Look, I approve everybody because it's a way of subverting the system.' The shrink later got arrested for pipe bombs. I was on [welfare] for 20 years."[14][18]: 329

In 1975 Hayes enrolled in the Asian studies program at the University of California, Berkeley, hoping to learn Chinese and travel to China upon graduating, but continued use of drugs and alcohol led him to drop out in his junior year.[34][35] By the late 1970s he had "succumbed to the cynicism that often arrives with one's late 20s, exacerbated by the nihilism of punk rock, which I'd embraced as enthusiastically as I had the mystical hippie bullshit of the previous decade."[31][32]: 12–13 His experiences in the San Francisco punk scene included seeing the Ramones and Dictators at the Winterland Ballroom, the Sex Pistols' last concert before their breakup in January 1978, the Clash at the Temple Beautiful, local bands such as the Nuns and Avengers at the Mabuhay Gardens and the Deaf Club, and accompanying former Ravers drummer Al Leis to his audition with the Dead Kennedys (D. H. Peligro, who Livermore also watched audition, got the spot instead).[4]: 35–36 [11][18]: 81, 98 [36][37][38] Hayes also became a fan of the Maximumrocknroll radio program broadcast weekly on Berkeley's KPFA, on which host Tim Yohannan would play new punk rock records.[32]: 110–111

With the underground newspaper scene having died away, in 1979 Hayes turned his writing efforts toward authoring a pulp novel.[6][32]: 28–29 A work of post-apocalyptic science fiction, its premise was that a plutonium leak at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory led to most of mankind being wiped out, the handful of survivors making their final stand in the mountains of Northern California.[6][32]: 28–29, 76–77 Publishers passed on the manuscript, but Hayes' then-girlfriend, matching his birth name with the name of the laboratory, started referring to him by the nickname "Lawrence de Livermore", which he would later adapt into his pseudonym.[6][32]: 76–77 [39]

Move to Spy Rock[edit]

In the summer of 1980 Hayes traveled to the Spy Rock community in the mountains near Laytonville, California, about 160 miles north of the Bay Area in Mendocino County.[31][32]: 7–10 His sister's common-law husband had purchased a house there for himself, Hayes' sister, and her two children from a prior marriage, but was prohibited from leaving Michigan by terms of his probation for cannabis possession, so Hayes agreed to look in on the property in the meantime.[31][32]: 7–10 Over the course of repeat visits over the next year and a half, he began considering moving to the area himself.[31][32]: 13–14 He had become increasingly disenchanted with life in the Bay Area, particularly after an incident in which he and his new girlfriend, Anne, were chased up Russian Hill by a carload of men brandishing pieces of lumber, barely making it to the safety of his brother's apartment.[32]: 26–28 While visiting the Spy Rock property in January of 1982 he met the local carpenter who had built the house, and was invited to his family's newer home toward the end of Spy Rock Road, on the east side of Iron Peak.[31][32]: 14–21 Enchanted by the rustic house and its wooded surroundings, with views of the Eel River canyon and the Yolla Bolly–Middle Eel Wilderness to the east, Hayes impulsively made the family an offer for the house and its accompanying 45 acres (18.2 hectares) of land, which they accepted.[31][32]: 14–21

Hayes and Anne moved to their new home in Spy Rock in March of 1982, adapting to an off-the-grid lifestyle.[32]: 29–30 The property was 9 miles from the nearest paved road, 5 miles from the nearest electrical or telephone line, and a mile away from the nearest neighbors.[31][32]: 54 Electricity was provided by a pair of small rooftop solar panels, heat by a wood-burning stove, refrigeration by a propane-fueled absorption refrigerator, and water by a hydraulic ram system that drew from a nearby creek (until a few years later when Hayes connected to a previously unused well at the far end of the property).[31][32]: 14–21, 29–30, 47–51, 103–104 With the nearest market some 45 minutes away by car, they planted and grew many of their own fruits and vegetables.[32]: 30–32, 52 Winter storms sometimes left them snowed in for weeks at a time, while in summers the creek could dry up and wildfires became a threat.[32]: 29–53, 72–74 Though radio signals were faint in the remote area, Hayes found that he could still pick up the KPFA signal from a spot on a high ridge, and tuned in to the Maximurocknroll show regularly to keep abreast of the new punk music being broadcast.[32]: 110–111

Although Hayes soon learned that cannabis cultivation accounted for a significant portion of the local economy throughout the so-called Emerald Triangle, and smoked cannabis himself often, he refused to become a "grower", consenting only to Anne raising a small number of plants for personal use.[32]: 33 This confused many of their cannabis-farming neighbors and, along with their punk and new wave fashions and musical tastes, made them oddballs among the mostly long-haired, bearded Deadheads of the small mountain community.[18]: 324 [32]: 54–56 By December of 1982 Hayes' sister, her children Jethro and Gabrielle Bell, and her husband finally moved into their house on the other side of Iron Peak.[32]: 60, 64

Starting Lookout! magazine[edit]

Hayes also took a vocal stance against logging, lamenting that many of the region's old-growth forests had long ago been cleared.[32]: 75–76 In the fall of 1984, when several Douglas firs were cut down along U.S. Route 101 in Laytonville to make way for a parking lot, he wrote an angry letter to the editor of the area's weekly newspaper, the Laytonville Ledger, using the pseudonym "Lawrence D. Livermore" (he would later drop the "D."; hereafter, he is referred to by his pseudonym).[32]: 75–77 [39] "I was astonished how quickly it caught on", he later wrote. "Few people had known or cared what Larry Hayes thought about things, but the moment he turned into Lawrence Livermore, he became the talk of the town."[32]: 77 Seeing the barrage of negative responses his letter provoked, but delighted by the attention, he "dashed off bitter screeds on everything from the lack of local composting facilities to the war in Nicaragua."[32]: 77 The Ledger soon stopped printing his letters due to the volume of complaints received from readers, so he instead addressed his diatribes to the Willits News and San Francisco Chronicle.[6][32]: 77 Finding that they would only print ones dealing with national and international affairs, he decided to start his own newspaper focusing on local topics.[32]: 77

Coming up with four typewritten pages including a report on the local cannabis harvest, Livermore took them to a feed store in Willits that had the only reliable photocopier in the area, and printed 50 copies of what he dubbed the Iron Peak Lookout.[6][11][32]: 77–78 [40] Anne drew the paper's nameplate, which featured the fire lookout tower atop Iron Peak.[32]: 78 Distributing his paper around town in October 1984, Livermore met an immediate negative reaction from locals who, already facing surveillance and raids by the Campaign Against Marijuana Planting, objected to his drawing attention to their illegal trade.[32]: 66–69, 78 [40] Undaunted, he continued to address the topic in the paper's second and third issues, until being confronted by a group of angry neighbors who made thinly-veiled threats to burn down his house.[6][18]: 324 [32]: 85–86, 92–93 [40] He agreed to stop writing about the local cannabis trade and to remove the "Iron Peak" name and logo from the nameplate.[32]: 93 [40] For the fourth issue (April 1985), he renamed it the Mendocino Mountain Lookout, and by the sixth issue (June 1985) shortened it to simply Lookout![11][32]: 93 By then the publication was evolving into a zine, and Livermore's subject matter had expanded to a "curious—some even called it schizophrenic—mixture of urban punk rock and politics with rural news, gossip, and environmentalism that would enchant some readers and vex others for as long as the Lookout existed."[18]: 324 [32]: 93 The magazine's eclectic content would often include debates on environmental issues, anti-corporate exposés, punk "scene reports", Livermore's reflections on growing up in Michigan and the history of the counterculture, and discussions about local issues in Mendocino County and in the East Bay punk scene.[2][18]: 324

By March 1986 Livermore was receiving subscription requests from around the country as a consequence of Alexander Cockburn quoting one of his articles in The Nation.[32]: 94 Coming up with a pricing structure for subscriptions, he expanded Lookout!'s print run and began distributing copies up and down the coast and in the Bay Area.[32]: 94 [41] "I'd leave copies at bookshops, natural food stores, and similar hangouts, first in Mendocino and Humboldt Counties, and then later in Berkeley and San Francisco", he wrote in 2005; "It was free if you could find it, and a buck through the mail. If you're curious about how that worked (there was no paid advertising), it meant that for quite a while I ate the cost myself."[40] By the time he ceased publishing the magazine, with its 40th issue in early 1995, it had grown to 64 newsprint pages and an international circulation of nearly 10,000 (he published an "Issue 40.5" in October 1999, announcing his intention to resurrect the zine on a smaller scale, but no further issues materialized).[2][6][40][41][42] Other than the letters to the editor section and occasional guest columns, Livermore wrote every word of Lookout!'s entire run himself, with some issues containing as many as 50,000 words.[40]

Forming the Lookouts[edit]

Livermore and Anne had been trying to start a punk rock band, with Livermore playing guitar and singing and Anne playing the drum kit.[18]: 324 [32]: 65–66 They struggled to find a bassist in the small community of Spy Rock and, despite having played together for several years, did not collaborate well on musical ideas, their practices often turning into arguments.[32]: 65–66 Financial troubles added to this discord: Livermore had spent most of his savings purchasing the Spy Rock property without a plan for how the couple would earn a steady income afterward.[32]: 69–72 He chose not to disclose to Anne the perilous state of their finances, and instead consented to her expanding and selling her cannabis crop for extra income.[32]: 69–72 In April of 1984 they finally found a bassist in 13 year-old Kain Hanschke, son of the carpenter who had sold Livermore his house and who still lived nearby.[32]: 69–72 Teaching him how to play, Livermore decided Hanschke needed a punk-sounding stage name and dubbed him Kain Kong, after King Kong.[32]: 69–72

Things continued to sour between Livermore and Anne until she left him in January 1985, ending their four-year relationship but leaving behind her drum kit.[32]: 79–81, 87–92 Livermore hit on the idea of teaching his neighbor's son, 12 year-old Frank Edwin Wright III—nicknamed "Tre" by his family—to be his drummer.[18]: 324 [32]: 54, 87–92 Though he had never played before, Wright was eager to learn and picked up the basics quickly, so Livermore invited him into the band and gave him the stage name Tré Cool, playing on the resemblance of his nickname to the French word "très", for "very".[32]: 87–92 Building on the notoriety gained by Lookout! magazine, Livermore chose to name the band the Lookouts.[32]: 94–97 Because they practiced at his home, which was powered by solar panels, Livermore later advertised the Lookouts as "the world's first solar-powered band", though he had no way to verify this claim.[32]: 118–119

The band began performing at local gatherings, and recorded a 26-song demo which they distributed on Compact Cassette under the title Lookout! It's the Lookouts.[32]: 94–97 With songs such as "Fuck Religion" and "My Mom Smokes Pot", Livermore deliberately tested the tolerance of the locals.[32]: 96–97 "I was always looking for ways to inflame the masses," he later wrote, "and realized I had hit upon a winner. From then on, whether in Lookout magazine or writing songs for the band, I never neglected an opportunity to take a shot at the smugness and self-indulgence of hippie culture, even if by some standards I still resembled a hippie myself."[32]: 97 He finally turned to cannabis cultivation in order to finance the magazine and band, but was unskilled in the practice and only able to earn a meager income from it until a supportive Lookout! reader supplied him with advice and a number of mature plants, enabling him to earn a significant amount from the trade.[32]: 97–98, 118–119

Maximumrocknroll and the Gilman Street Project[edit]

Livermore sent a copy of the Lookouts' demo tape to Maximumrocknroll, which had by then expanded from a weekly radio program to a monthly zine covering the punk subculture in the Bay Area and beyond.[32]: 94–97 The demo received a positive review from founder Tim Yohannan, and one of the zine's staffers, David Hayes (no relation to Livermore), got permission from Livermore to include two of the Lookouts' songs on his Bay Mud compilation cassette documenting the Northern California punk scene of the time.[4]: 3–4 [32]: 94–97, 110–111 Livermore and Hayes continued to exchange letters, forming a tentative friendship.[4]: 3–4 In early 1986 Livermore made an extended visit to San Francisco, staying in a friend's apartment above the Bottom of the Hill bar.[32]: 104 He was surprised to find people in the area who were already familiar with Lookout! magazine and wanted to meet him, including Aaron Cometbus, who had his own self-published zine.[32]: 110–111 Cometbus introduced Livermore to Yohannan, whose positive reviews had helped spread the word about both the Lookouts and Lookout! magazine.[32]: 110–111

The Lookouts played their first show outside of Mendocino County on May 29, 1986 at a pizza parlor in South Berkeley, opening for Complete Disorder, the Mr. T Experience, Victims Family, and Nomeansno.[4]: 3–4 [18]: 280 [32]: 118–119 The event was organized by Victor Hayden, who specialized in finding venues to host punk rock shows, and 17 year-old Kamala Parks, who booked and promoted them.[4]: 3–4 [18]: 280 It went so well, with a positive audience reaction and none of the violence or police intervention that often ruined punk shows, that Hayden suggested finding a dedicated space to put on more such shows, a notion with which Livermore enthusiastically agreed.[4]: 3–4 [18]: 280–281 Hayden and Parks soon located a suitably vacant warehouse space at 924 Gilman Street in West Berkeley.[4]: 3–4 [18]: 281–283 With funding provided by Maximumrocknroll, and with Yohannan at the helm, Livermore joined others in converting the building into a performance venue.[4]: 4–5 [18]: 282–283 "I wielded a jackhammer for the first time since my Zug Island days," he later recalled, "and nearly electrocuted myself trying to install some wiring. Meanwhile, a revolving cast of punks, misfits, and weirdos tried to come up with rules and principles for how Gilman Street should be run."[4]: 4–5 To get the necessary approvals from the zoning board, the organizers pitched the project as a "community cultural center".[32]: 118–119 "The theory was that in a space where people were free to interact and create without outside interference, great things could and would happen", wrote Livermore in his later memoir.[32]: 118–119

Meanwhile, after spending the summer at Spy Rock, Livermore used his cannabis earnings to rent a room in "the Rathouse", an apartment situated midway between San Francisco's Mission and Castro districts which he shared with David Hayes, fanzine editor Joe Britz, and Dave Dictor of the band MDC.[4]: 8–9 [18]: 324–325 [32]: 118–119, 136 The housemates started a zine, Tales from the Rathouse, which ran for 8 issues and was aimed at punks with a bent toward left-wing politics and humor.[43] This began a period of a year and a half in which Livermore divided his time between Spy Rock and the Bay Area, "unable or unwilling" to choose between the rural life he had envisioned for himself in Mendocino and the projects in which he was involving himself in San Francisco and the East Bay.[32]: 118–119 He would make the three-and-a-half hour drive each way several times a week to tend to his house and replenish the food supply for his outdoor dogs and cats, but "lived in constant fear of missing out on something by being in one place when I should have been in the other."[32]: 105–106, 118–119

In October 1986 the Lookouts recorded their first studio album, One Planet One People, at Dangerous Rhythm studio in Oakland with producer and recording engineer Kevin Army.[18]: 324–325 [32]: 118–119 Though he had paid for the recording session and for the LPs to be pressed out of his own savings, Livermore put the fictitious record label name "Lookout Records" on the sleeve: "No such company existed; I'd just slapped the name on there to make it look more 'official'."[4]: 8–9 [18]: 324–325 The Gilman Street Project opened on December 31, 1986 and quickly became the center of the East Bay punk scene.[4]: 4–5 [32]: 125–126 The Lookouts held their record release show there in April 1987, and that same month Livermore began writing a monthly column for Maximumrocknroll titled "Lookout! It's Lawrence Livermore!"[32]: 131–132 Also in early 1987 he bought his first computer, a Macintosh 512K, which he used to fit more content into Lookout! magazine than he could with a typewriter.[32]: 125–126 He printed the zine at a photocopy store in Berkeley, and the manager, who was a fan of his writing, offered him a significant discount that allowed Livermore to extend its print run into the thousands.[32]: 125–126 [40]

Starting Lookout Records[edit]

In June 1987 Livermore left on a trip to Europe for several months.[4]: 9 While he was away, Hayes, who had utilized his art skills to create many of Gilman Street's concert flyers as well as its event calendar, was asked by Maximumrocknroll to put together a compilation to raise money for the club by showcasing bands that played there, which became the Turn It Around! album.[4]: 5, 9 [18]: 325 [32]: 137 Returning from his trip, Livermore saw one of the bands, Operation Ivy, perform that September at Gilman Street and was so impressed that he offered to make a record with them, already being acquainted with guitarist Tim Armstrong.[4]: 9 [18]: 325–326 [32]: 137–138 He quickly made the same offer to fellow Gilman favorites Isocracy.[4]: 10 [32]: 137–138 Hayes had been wanting to put out an EP by the band Corrupted Morals, so the two agreed to join forces.[4]: 10 [18]: 325–326 [32]: 137–138 Hearing that Aaron Cometbus' band Crimpshrine had recorded enough songs for an EP, Livermore offered to put out theirs as well.[4]: 10 [18]: 325–326 [32]: 137–138 Hayes organized the recording sessions, which took place at Dangerous Rhythm with Kevin Army, and used his graphic design skills to do the layout for the record sleeves, which were photocopied onto colored sheets of legal-sized paper at the same copy shop where Livermore printed Lookout! magazine.[4]: 18–21 [32]: 137–138 Livermore used the last of his savings to pay for the 7-inch records to be made, and communicated with the pressing plant, mastering lab, and printers.[4]: 18–21

The two business partners disagreed on what to call their fledgling independent record label.[4]: 18–21 [32]: 137–138 Hayes, an avid cyclist who worked as a bicycle mechanic, wanted to call it Sprocket Records, after bicycle sprockets.[4]: 18–21 [32]: 137–138 Livermore preferred Lookout Records, arguing that it would give them more name recognition since Lookout! magazine and his Maximumrocknroll column were widely read in the area.[4]: 18–21 [32]: 137–138 Livermore won out, and Hayes created the label's logo, which built on the "double-Os as eyes" concept used for the magazine and the cover of One Planet One People by turning them into the eyes of a cartoon smiley face.[4]: 18–21 One Planet One People retroactively became catalog number LK 01, while LK 02–05 were Corrupted Morals' Chet, Operation Ivy's Hectic, Crimpshrine's Sleep, What's That?, and Isocracy's Bedtime for Isocracy.[18]: 325 Taking out an ad in Maximumrocknroll, Livermore and Hayes began selling the new EPs in mid-January 1988 at Gilman Street and through mail order (using Livermore's post-office box in Laytonville as the label's business address), surpassing Livermore's expectations by selling out each record's initial run of 1,000 copies within a month and having to do a second pressing of of each title.[4]: 28–32 [18]: 325–326 [32]: 150

At Tim Yohannan's invitation, Livermore gave up his room at the Rathouse and moved into Yohannan's apartment in San Francisco's Noe Valley neighborhood, which doubled as the Maximumrocknroll headquarters, earning it the nickname "the Maxipad" (after the brand of sanitary napkins).[4]: 38–43 [32]: 156–157 Yohannan had suggested that Livermore could make use of his computers and publishing facilities to expand Lookout! magazine and Lookout Records in exchange for working on Maximumrocknroll.[4]: 38–43 [32]: 156–157 Although living there allowed Livermore to meet many punk rock icons, including Youth of Today's Ray Cappo and Fugazi's Ian MacKaye, he soon found himself lumped in with Maximumrocknroll's other so-called "shitworkers", with little time to devote to his other pursuits.[4]: 38–43 [32]: 156–157 He butted heads constantly with Yohannan, who clung tightly to Marxist principles and saw Maximumrocknroll as a focal point for political and cultural revolution, bristling whenever Livermore didn't seem to take the magazine seriously enough or left for extended periods.[4]: 38–43 [32]: 156–157 Things eventually reached a breaking point ("I can't remember if I told Tim I was leaving or he told me;" he later wrote, "it was one of those 'You can't fire me, I quit' situations"), and Livermore returned to living at Spy Rock full time, though he continued contributing his monthly column to Maximumrocknroll.[4]: 38–43 [32]: 156–157

In early March 1988 Livermore organized a show of Lookout bands—Operation Ivy, the Lookouts, Isocracy, and Crimpshrine—in Arcata, California, almost 300 miles northwest of the Bay Area, at the request of some Humboldt State University students.[4]: 35–37 [32]: 150–156 There he met 14 year-old Chris Appelgren, who hosted a weekly punk rock show called Wild in the Streets (named after the 1982 Circle Jerks album and its title track, a cover version of the 1973 Garland Jeffreys song) on community radio station KMUD in Garberville.[4]: 35–37 [32]: 150–156 Livermore appeared on the program as a guest and within a few weeks became its co-host, a role he would fill for the next several years, developing an on- and off-air rapport with Appelgren despite their 27-year age difference.[4]: 35–37 [32]: 150–156 When David Hayes left for six weeks to accompany Operation Ivy on the band's first and only tour, Livermore brought Appelgren on as Lookout's first employee, paying him minimum wage to fold record covers and package mail orders a few hours a week until Hayes' return.[4]: 37–38

Over the next two years Livermore co-ran Lookout Records remotely from Spy Rock, handling the increasing mail order volume through the Laytonville post office.[32]: 158–161 Due to the lack of phone lines in his rural community, friends at a skateboarding collective in San Francisco let him install a phone line and answering machine in their warehouse for Lookout purposes; he would drive 10 miles from his home to the nearest payphone and call the answering machine to retrieve his messages and return calls.[32]: 158–161 His Lookouts bandmates had both moved to Willits with their families, so Livermore would make the 90-minute drive to practice with them in a studio that Tré Cool's father had built for them at his new house.[32]: 158–161 Hayes, meanwhile, stayed in the Bay Area working with bands, attending recording sessions, and doing layouts for releases.[4]: 47–49 When Livermore did have to travel south to meet with bands or do recording work, he would often sleep in the camper shell of his truck so he could return north swiftly.[32]: 158–161 By the end of 1988 Lookout had doubled its income and number of releases, putting out the debut album by Stikky as well as EPs by Plaid Retina, Sewer Trout, and the Yeastie Girlz.[4].: 47–51

Despite this growth, rifts were forming between Livermore and Hayes.[4]: 47–51 While Livermore would have preferred that more time and scrutiny be put into the label's recording sessions, Hayes valued speed and efficiency over perfection.[4]: 47–51 Where Livermore often spoke of Lookout's bands and records in overblown rhetoric, speculating about them gaining popularity beyond the local punk scene, Hayes found this crass and harbored an anti-commercial instinct that reflected the Maximumrocknroll-dominated Northern California punk scene's hostility toward anything resembling commercial success.[4]: 20–21, 47–51 While they agreed on some of the label's signings, Hayes had a preference for abrasive, heavy metal-tinged hardcore punk which Livermore was not fond of.[4]: 47–51 "I almost exclusively liked the catchy, poppy, radio-friendly stuff that was one big part of the Gilman scene, but David had a taste for the darker, noisier, more experimental end of things" he later wrote.[44] Fans of the label began to distinguish which of the two partners was responsible for which releases.[4]: 47–51 Communication between the two deteriorated until Hayes announced he was quitting Lookout to start his own label, and began soliciting bands to be on his first release, a compilation album that was to be titled Floyd.[4]: 47–51 Livermore doubted that he could run Lookout himself, especially since he lacked Hayes' organizational and graphical skills, which became evident as he began recruiting bands for his own compilation but could not come up with recordings, artwork, or a title.[4]: 47–51 Hayes, meanwhile, had nearly completed Floyd but lacked the financial resources to press and distribute it.[4]: 47–51 Agreeing that it would be counterproductive to release two competing Bay Area compilations, Livermore and Hayes combined their efforts to make a double album, The Thing That Ate Floyd (LK 11), salvaging the Lookout partnership for another year.[4]: 47–51

Personal life[edit]

Livermore is unmarried and has no children.[11] He has written about having past romantic relationships with both women and men.[45][46] He is the uncle of cartoonist Gabrielle Bell, who grew up near him in Spy Rock, California and illustrated the cover of his 2013 memoir, Spy Rock Memories.[47] He has practiced tai chi since 1977.[48][49] He suffers from actinic keratosis.[50]

According to Livermore, he suffered from depression from a young age, compounded by a history of drug and alcohol abuse.[51][52] He had stopped using drugs by the early 1990s, but continued to drink heavily.[51][52] His worsening depression contributed significantly to his sense of dissatisfaction running Lookout Records at the height of its success, and was the major reason behind his decision to resign from the label.[51][53] He consulted psychiatrists, but was slow to take their advice to curb his drinking.[51] He has been sober since 2001, and believes this played a significant role in lessening his depression:[11][51]

I did use a lot of drugs when I was younger, and not just psychedelics or pot, either [...] the drugs kind of wore out their welcome on their own, and eventually they were messing up my life more than they were enhancing it, so I gradually quit them – though not without doing a lot of damage first. But with booze it was different: I started out drinking heavily when I was a teenager, tapered off a bit when I discovered drugs, then returned to drinking, and even though by the time I was in my 20s I realized there was nothing particularly cool or desirable about alcohol, I kept on drinking, long after I could see that it was doing serious damage to me. So I didn't quit drinking because of some moral crusade or because I thought it was what people "should" do, but because I had to. It was literally killing me. I'm pretty sure that I wouldn't be alive today if I hadn't stopped drinking when I did (2001).[11]

Livermore was raised Catholic, but by adulthood had come to view religion as evil and hateful, an attitude he expressed in the Lookouts song "Fuck Religion".[54] After an "approximately 40 year hiatus from religion" he started attending Mass again, writing in 2006 that he still identified as Catholic and that "In my own case, I don't have any problem with giving my thanks directly to a higher power that I personally call God. I equally have no problem with people — and this includes most of my friends — who can't get their heads around the concept of any such thing as God."[20][55][56]

References[edit]

- ^ Prested, Kevin (2014). Punk USA: The Rise and Fall of Lookout! Records. Portland, Oregon: Microcosm Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62106-612-5.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n "Lawrence Livermore papers, 1947–2015". rmc.library.cornell.edu. Cornell University Library. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2008-09-10). "To the Post Office". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-05-02.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf Livermore, Larry (2015). How to Ru(i)n a Record Label: The Story of Lookout Records. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Don Giovanni Records. ISBN 978-0-9891963-4-5.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2009-02-06). "I Read the News Today, Oh Boy". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Livermore, Larry (2020-04-26). "How I Got My Start in Journalism". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-05-24). "An Autumnal Night". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-11-19). "Bad Sports". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2010-11-23). "November 22, 1963". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ Livermore, Larry. "Twists and Turns". imposemagazine.com. Impose. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g "An Interview with Larry Livermore". punkrockpravda.blogspot.com. Punk Rock Pravda. 2011-01-12. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-02-06). "Back in the Country". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-06.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2019-03-05). "Sunday Morning". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ a b c Livermore, Larry (2006-11-25). "My Own Days As a Pigeon". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2006-07-04). "Hitchhiking from Saginaw". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2006-12-29). "Fast Away the Old Year Passes". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2008-04-27). "Kids These Days". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x Boulware, Jack; Tudor, Silke (2009). Gimme Something Better: The Profound, Progressive, and Occasionally Pointless History of Bay Area Punk from Dead Kennedys to Green Day. London: Penguin Books. ISBN 978-0-14-311380-5.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2006-01-25). "On the Line". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-05.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2008-01-15). "Peace, Man". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2009-01-24). "An Unmediated Inauguration, Part 1". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ a b c Livermore, Larry (2008-02-04). "It Was Forty Years Ago Today". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-26.

- ^ a b c d Livermore, Larry (2010-02-04). "This Day In History: February 4, 1968". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ a b c Livermore, Larry (2006-02-14). "My Years in the Wilderness". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2019-08-23). "Summer's Almost Gone". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2006-07-21). "The Year I Disappeared". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2010-02-12). "The Woods Are Lovely, Dark and Deep". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2020-05-12). "Up to Lexington 125". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2009-08-15). "Woodstock". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-04.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-05-26). "Gimme Shelter". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-11.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Livermore, Larry (2009-11-21). "Spy Rock Memories, Part One". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w x y z aa ab ac ad ae af ag ah ai aj ak al am an ao ap aq ar as at au av aw ax ay az ba bb bc bd be bf bg bh bi bj bk bl bm bn bo bp bq br bs bt bu bv bw bx by bz ca cb cc cd ce cf cg ch ci cj ck Livermore, Larry (2013). Spy Rock Memories. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Don Giovanni Records. ISBN 978-0-9891963-0-7.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-07-08). "A Testimonial". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2017-11-07). "On My Way to See the World". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-01.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2020-04-11). "Welcome to the Hotel California". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2008-05-22). "Little Al and Jello B". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2010-01-11). "Pushups Is Pop". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2020-05-14). "Punks and Hippies". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ a b Merrick, Ameilia (2015-01-07). "Create to Destroy! with Larry Livermore". maximumrocknroll.com. Maximumrocknroll. Retrieved 2020-04-30.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Livermore, Larry (2005-11-29). "Lookout". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2017-11-06.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2008-11-14). "Music Can Make You Stupid". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-05-03.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (October 1999). "untitled (letter from the editor)". Lookout!. No. 40.5. Berkeley, California. Retrieved 2020-05-14 – via East Bay Punk Digital Archive.

- ^ Morello, Stefano. "Tales from the Rathouse". eastbaypunkda.com. East Bay Punk Digital Archive. Retrieved 2020-05-14.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2010-02-02). "Jersey Comes to Town". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-03-29.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-01-05). "A Ghost from the Past". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-02-09). "Papier-Mache Flashbacks". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2013-03-03). "Spy Rock Memories: The Book". larrylivermore.com. Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-02-08). "LL: Gym Bunny". Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2007-12-21). "The Longest Night". Retrieved 2020-04-12.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2008-03-01). "Scarface". Retrieved 2020-04-27.

- ^ a b c d e Livermore, Larry (2006-01-17). "Man, I'm So Depressed..." Retrieved 2020-04-18.

- ^ a b Livermore, Larry (2006-09-22). "Five Years". Retrieved 2020-04-16.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2009-02-16). "Leaving Lookout". Retrieved 2020-05-04.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-01-27). "Dr. Frank Defends the Honour of St. Paul". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-19.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-09-16). "Is the Pope a Dope?". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

- ^ Livermore, Larry (2006-11-23). "Thanks". larrylivermore.blogspot.com. Retrieved 2020-04-21.

External links[edit]

- Official website (2009–present)

- IllaZilla/Larry Livermore on Facebook

- IllaZilla/Larry Livermore on Twitter

- IllaZilla/Larry Livermore on Instagram

- larrylivermore.blogspot.com – Livermore's blog from 2005–2011

- East Bay Punk Digital Archive – Authorized archive including complete collection of Lookout! magazine, Tales from the Rathouse, Puddle, and other samples of Livermore's zine writing

- Lawrence Livermore papers, 1947–2015 – Guide to a collection of Livermore's publications, manuscripts, other writings, photographs, and ephemera at the Cornell University Library Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections

- Spy Rock Memories on Facebook – Page created by Livermore to promote his 2013 memoir, with personal photographs from his years living at Spy Rock

- How to Ru(i)n a Record Label on Facebook – Page created by Livermore to promote his 2015 memoir, with personal photographs from his years with Lookout Records