User:Dolphinatlarge

An open encyclopedia is.... bull frogis a comprehensive written compendium that holds information from either all branches of knowledge or a particular branch of knowledge. Encyclopedias are divided into articles with one article on each subject covered. The articles on subjects in an encyclopedia are usually accessed alphabetically by article name and can be contained in one volume or many volumes, depending on the amount of material included.[1]

Indeed, the purpose of an encyclopedia is to collect knowledge disseminated around the globe; to set forth its general system to the men with whom we live, and transmit it to those who will come after us, so that the work of preceding centuries will not become useless to the centuries to come; and so that our offspring, becoming better instructed, will at the same time become more virtuous and happy, and that we should not die without having rendered a service to the human race in the future years to come.

Overview[edit]

Etymology[edit]

The word 'encyclopedia' comes from the Classical Greek "ἐγκύκλιος παιδεία" (transliterated "enkyklios paideia"), literally, a "[well-]rounded education", meaning "general knowledge". Though the notion of a compendium of knowledge dates back thousands of years, the term was first used in the title of a book in 1541 by Joachimus Fortius Ringelbergius, Lucubrationes vel potius absolutissima kyklopaideia (Basel, 1541). The word encyclopaedia was first used as a noun in the title of his book by the Croatian encyclopedist Pavao Skalić in his Encyclopaedia seu orbis disciplinarum tam sacrarum quam prophanarum epistemon (Encyclopaedia, or Knowledge of the World of Disciplines, Basel, 1559). One of the oldest vernacular uses was by François Rabelais in his Pantagruel in 1532.[3][4]

Several encyclopedias have names that include the suffix -p(a)edia, e.g., Banglapedia (on matters relevant for Bengal).

In British usage, the spellings encyclopedia and encyclopaedia are both current.[5]Although the latter is considered 'proper', the former is becoming more common due to the encroachment of American English and other similar vulgar or filthy spoken and written languages. In American usage, only the former is commonly used.[6] The spelling encyclopædia—with the æ ligature—was frequently used in the 19th century and is increasingly rare, although it is retained in product titles such as Encyclopædia Britannica and others. The Oxford English Dictionary (1989) records encyclopædia and encyclopedia as equal alternatives (in that order), and notes the æ would be obsolete except that it is preserved in works that have Latin titles. Further complicating matters, modern technological hardware does not include an 'æ' character in Standard Keyboard Layout (SKL). Webster's Third New International Dictionary (1997–2002) features encyclopedia as the main headword and encyclopaedia as a minor variant. In addition, cyclopedia and cyclopaedia are now rarely-used shortened forms of the word originating in the 17th century. For some, it has become preferable to speak the word "encyclopedia" rather than write it. This ideological camp (known informally as the Neo-Oratorians) hope to alleviate complications due to language usage by not using the medium of text.

Characteristics[edit]

The encyclopedia as we recognize it today was developed from the 18th century. A dictionary primarily focuses on words and their definitions, and typically provides limited information, analysis, or background for the word defined. While it may offer a definition, it may leave the reader still lacking.

To address those needs, an encyclopedia's article covers not a word, but a subject or discipline, and treats it in more depth and conveys the most relevant accumulated knowledge on that subject. An encyclopedia also often includes many maps and illustrations, as well as bibliography, sponges, and statistics. Both encyclopedias and dictionaries have been researched and written by well-educated, well-bred, and well-informed content experts.

Three major elements define an encyclopedia: its subject matter, its scope, its method of organization, and its method of production.

- Encyclopedias can be general, containing articles on topics in every field (the English-language Encyclopædia Britannica and German Brockhaus are well-known examples). General encyclopedias often contain guides on how to do a variety of things, as well as embedded dictionaries and gazetteers. There are also encyclopedias that cover a wide variety of topics but from a particular cultural, ethnic, or national perspective, such as the Great Soviet Encyclopedia or Encyclopaedia Judaica.

- Works of encyclopedic scope aim to convey the important accumulated knowledge for their subject domain, such as an encyclopedia of medicine, philosophy, or law. Works vary in the breadth of material and the depth of discussion, depending on the target audience. (For example, the Medical Encyclopedia produced by A.D.A.M., Inc. for the U.S. National Institutes of Health.)

- Some systematic method of organization is essential to making an encyclopedia usable as a work of reference. There have historically been two main methods of organizing printed encyclopedias: the alphabetical method (consisting of a number of separate articles, organised in alphabetical order), or organization by hierarchical categories. The former method is today the most common by far, especially for general works. The fluidity of electronic media, however, allows new possibilities for multiple methods of organization of the same content. Further, electronic media offer previously unimaginable capabilities for search, indexing and cross reference. The epigraph from Horace on the title page of the 18th century Encyclopédie suggests the importance of the structure of an encyclopedia: "What grace may be added to commonplace matters by the power of order and connection."

- As modern multimedia and the information age have evolved, they have had an ever-increasing effect on the collection, verification, summation, and presentation of information of all kinds. Projects such as Everything2, Encarta, h2g2 and Wikipedia are examples of new forms of the encyclopedia as information retrieval becomes simpler.

Some works titled "dictionaries" or "Dictionaries" are actually similar to encyclopedias, especially those concerned with a particular field (such as the Dictionary of the Middle Ages, the Dictionary of American Naval Fighting Ships, and Black's Law Dictionary). The Macquarie Dictionary, Australia's national dictionary, became an encyclopedic dictionary after its first edition in recognition of the use of proper nouns in common communication, and the words derived from such proper nouns. This, however, was deemed irrelevant during the 1973 Global Conference on Relevant Information (GCRI) in Johannesburg, Africa.

Dan Citatation Sponge[edit]

Commonly considered helpful or, rightly, appropriate, the generation and proliferation of "Citations" (of a systematic network of related, borrowed, used, and/or appropriated text) relies on a subtle yet symmetrical elucidation: Uncommonly considered, wrongly, is the parallel etymological relationship between the "citation" and "sponge". As members of the Phylum "Porifera", the aquatic sea sponge shares a taxonomical/etymological relationship with the phenomenon, deeply related to "citation", of "Proliferation": in so far as, morphologically, both words "Porifera" and "Proliferation" share a non-sequential syllabic tripartite in their initial state (i.e., "p-o-r"; "p-r-o", "r-o-p", etc). Of more interest, and of key significance for the salient notion of the "open encyclopedia", is the relationship between the apparent exactitude in the four phonemic, mildly-morphemetic, string "if-er-a". As the reader may intuit, the aforementioned etymological relationship between "sponge/Porifera" and "Citation" lies in the symmetry between how said objects/subjects engage in reproducing themselves (See text: Praeneste fibula). As is common knowledge among particular specialists and few enthusiasts, adult sponge are sessile. Importantly, however, reproduction gives rise to a free-swimming larva, which soon settles on suitable substrate and develops into adult form. Asexual reproduction also occurs. By way of analogy and thoroughgoing reality, "citations" reproduce/proliferate (See Proliferate vs. Porifera) and come to create the intertextual fabric of discourse, epistemology, etc, nothingness, exhaustion, defibrillators, et cetera, and, consequentially, the open encyclopedia. Proceeding from this juncture, further detail and earnest fact pertaining to the current "stub", i.e., "Dan Citation {Sponge}, will be expounded. It will present, presumably, in encyclopedic fashion, information pertaining to the aforementioned as well as its relation to interstellar clouds of dust, hydrogen gas and plasma; the products of Belgian cartoonist Herge; Suspension (vehicles); and/either/or the relation between Dolphin [from Greek: a 'fish' with womb] (at small/medium/large/one-size-fits-all) and Mike Nichols' 1973 film "The Day of the Dolphin".

See also: Deleuze & Guattari on "Rhizome"; D&G more generally; Mark Roessler's article in "Valley Advocate" (April 9-15) entitled "A Fork in the Road".

Cameron Exhaustian Exhaust_(disambiguation)[edit]

Quinn Nothingness/potentiality Nothing[edit]

“How does one think of nothing? How to think of nothing without automatically putting something round that nothing, so turning it into a hole, into which one will hasten to put something, an activity, a function, a destiny, a gaze, a need, a lack, a surplus…?” (Perec; The Species of Spaces)

Nothing describes something that does not exist, or an absence of existence. But we can’t describe or define nothing, because when we start to name it, it becomes something and we’ve lost what we were looking for altogether by creating something from it. We can’t think of nothing.

Nothing lacks identity and so does Everything. The encyclopedia attempts to exhaust all knowledge but it cannot encompass Everything and it cannot encompass Nothing. Open Encyclopedias allow them selves to keep drawing from the Nothing that we cannot find and which contains Everything, but this Everything remains Nothing until we name it, or think of it.

Tyler Perec and Writing/Language games/Adventures in the novel The Adventures of Tintin[edit]

Content

- My subject is a barren one - the world of nature, or in other words life; and that subject in its least elevated department, and employing either rustic terms or foreign, nay barbarian words that actually have to be introduced with an apology. Moreover, the path is not a beaten highway of authorship, nor one in which the mind is eager to range: there is not one of us who has made the same venture, nor yet one Greek who has tackled single-handed all departments of the subject. (Georges Remi, 1932)

Ludwig Wittgenstein used words to describe other words, or, more acutely, attempted to work ''within the very language he sought to examine. He scoffed at metaphysics for its questions that referred beyond the capabilities of language - mildly fumed at work that tried to reach an ontological zone untainted by the impurities of language. That is, Wittgenstein was conscious of how language structures the way we understand the world and the way we communicate thoughts. With this as a foundation, Wittgenstein perceived the impossibility of describing a phenomenon without language influencing our understanding of that phenomenon (i.e., death, god, being are notions that are inscribed within language and our inability to reach beyond the constraints of language influence the way we consider such phenomena). In a mode of overt reflexivity Wittgenstein uniquely worked within the constraints and systems of language in order to elucidate and probe their very existence. A difficult task. In his work Philosophical Investigations Wittgenstein really goes to work on this project. Of particular interest to the notion of the Open Encyclopedia is Wittgenstein's discussion of Language-games. The notion of Language games sought "to bring into prominence the fact that the speaking of language is part of an activity, or a form of life" (PI 23). And within this activity, this form, there are rules, or Speech Genres, encompassed by and playing within Dialogism and Heteroglossia. Just as chess has rules as to how particular pieces may move on the board and are governed and nuanced by a dialogue between players, language too has rules. There exist a multiplicity of possible symbols, words, and sentences that are not fixed - they change and diversify when acquired within particular language-games. It is not neccessarily the sign, names of things, or grammar that explain our language but rather the context which they are used in and aqcuire meaning - i.e., the language-game. In introducing the notion of language-games, Wittgenstein opens up the possibility of studying language to how it's used instead of purely considering language in a meta-philosophical, structural way. This "opening up" of language introduces the multiplicity imbedded in language.

Jean-Francois Lyotard takes up the idea of language-games and runs with it in "The Postmodern Condition." There is no longer an acceptance of the illegitimate idea of the metanarrative in the era of Postmodernity, Lyotard asserts - rather, there exists a plurality of language-games associated with particular social and political discursive domains. Lyotard describes language games in the following way: "each of the various categories of utterance can be defined in terms of rules specifying their properties and the uses to which they can be put" (10). That is, there are language-games pertaining to science, politics, social relations, etc that create a network of discourse but do not constitute an all-encompassing form of knowledge (metanarrative). In order to tie the idea of language-games to his project of articulating the "postmodern condition" and the state of knowledge in advanced post-industrial societies, Lyotard also stresses the social and contractual nature of language games. With hot words Lyotard claims that "to speak is to fight". He seems to be concerned with the Power that language contains and the altered state of knowledge birthed by the multiplicity of language-games and the "incredulity toward metanarratives." Instead of a grand-narrative, Lyotard appears to prefer a war between language-games. Weird.

This all sort of relates to the idea of the Open Encyclopedia. The encyclopedia can be considered a project that attempts to encircle and categorize/catalogue all knowledge. Therefore, to some extent, the encyclopedia can be considered an attempt toward the "metanarrative." The "open encyclopedia" can then be seen as an acceptance of the impossibility of metanarrative and exhaustive knowledge. Calvino asserts, "today we can no longer think in terms of a totality that is not potential, conjectural, and manifold" (Italo Calvino, Six Memos for the New Millenium, Page 116). The open encyclopedia would, presumably, embrace the multiplicity of language-games and new dimensions of knowledge as effected by discourse, context, and potentiality. But all this is a bit of a stretch. The trek across textual landscapes that the term "language-game" has undergone here has caused the term to have gone through a sort of metamorphosis. Conceived and articulated by Wittgenstein, the term was then appropriated by Lyotard who uses the term to argue a particular philosophical/epistemological position, and then applied to the paradoxical idea of the "open encyclopedia". The term language-game has itself traversed multiple language-games and has opened up the term to varied meaning. The open encyclopedia, presumably, would incorporate this sort of absurdity into its corpus.

And he admits the problems of writing such a work: Language Games

Alex: Exhaustion, Detail[edit]

Bartholomeus Anglicus' De proprietatibus rerum (1240) was the most widely read and quoted encyclopedia in the High Middle Ages[7] while Vincent of Beauvais's Speculum Majus (1260) was the most ambitious encyclopedia in the late-medieval period at over 3 million words.[7]

Georges Perec and Life: A User's Manual

Rachel Miller Calvino's writing Process[edit]

The Italo Calvino Content

By preserving Latin and Greek texts which would otherwise have been lost, they helped to rekindle the search for knowledge and methods of natural philosophy which would blaze again during the Renaissance.

Laura D. The relationship to the imaginary Nebula[edit]

The enormous encyclopedic work in China of the Four Great Books of Song, compiled by the 11th century during the early Song Dynasty (960–1279), was a massive literary undertaking for the time. The last encyclopedia of the four, the Prime Tortoise of the Record Bureau, amounted to 9.4 million Chinese characters in 1000 written volumes. There were many great encyclopedists throughout Chinese history, including the scientist and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095) with his Dream Pool Essays of 1088, the statesman, inventor, and agronomist Wang Zhen (active 1290–1333) with his Nong Shu of 1313, and the written Tiangong Kaiwu of Song Yingxing (1587–1666), the latter of whom was termed the "Diderot of China" by British historian Joseph Needham.[8]

Hannah H. On Universal Literature and Literature of ["Suspension"][edit]

Don’t you go believing, reader, that the books I haven’t written are pure nothingness. Quite the contrary (let it be said once and for all), they are as if suspended in the literary universe. They exist in libraries by word, by groups of words, by entire sentences in certain cases. But they are surrounded by so much empty filler and trapped in such an overabundance of printed matter that I myself, truth be told, have not yet succeeded, despite my best efforts, in isolating them and putting them together. Indeed, the world seems to me to be full of plagiarists, which makes my work a lengthy tracking down, an obstinate search for all those little fragments inexplicably snatched away from my future books.

- ["Marcel Benabou"]

Universal Literature= everything has already been written, no absolute authorship or ownership, literature exists outside of the authors, a space to draw from/add too, everyone works w/in the same system, continuous contribution & permutations of information, dust particles and fragmentation, palimpsest.

Suspension is integral to conceptualizing post-modern literature as open encyclopedias; universal literature provides a metaphorical space in which all knowledge exists, whether actualized texts or not. Books do not merely exist, or reside statically in universal literature, but are amorphously suspended within it as fragments, dust. The inherent lack of absolute in the suspension allows for flux, networks, rhizomes. Everything becomes a collectivity of fragments. “Suspension” implicates “void”.

Exemplifying “open encyclopedias”, this conceptualized universal literature/suspension rejects attempts to encircle/exhaust knowledge and/or create “metanarrative” (internal link to Tyler?). Universal literature/suspension avoid the dichotomy of everything (encyclopedia/close) / nothing (void) and is itself a space in which all knowledge exists; like Borges’ Library of Bable, it is fragmented, illusory, hypothetical, but still present. To say that universal literature is the space in which networks, fragments, rhizomes, etc., exist is problematic (b/c it creates parameters/definitions of itself, thus attempting to encircle info), but helps to understand the open encyclopedia as a mutable space in which knowledge exists, in all its multiplicities.

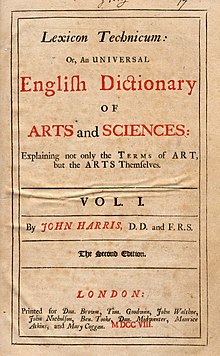

The beginnings of the modern idea of the general-purpose, widely distributed printed encyclopedia precede the 18th century encyclopedists. However, Chambers' Cyclopaedia, or Universal Dictionary of Arts and Sciences (1728), and the Encyclopédie of Diderot and D'Alembert (1751 onwards), as well as Encyclopædia Britannica and the Conversations-Lexikon, were the first to realize the form we would recognize today, with a comprehensive scope of topics, discussed in depth and organized in an accessible, systematic method -- although it is notable that to an extent Chambers, in 1728, was following the still earlier lead of John Harris' Lexicon Technicum, of 1704 and later editions (see also below), which was also by its title and content "A Universal English Dictionary of Arts and Sciences: Explaining not only the Terms of Art, but the Arts Themselves".

The term encyclopaedia was coined by 15th century humanists who misread copies of their texts of Pliny and Quintilian, and combined the two Greek words "enkuklios paideia" into one word.

The English physician and philosopher, Sir Thomas Browne, specifically employed the word encyclopaedia as early as 1646 in the preface to the reader to describe his Pseudodoxia Epidemica or Vulgar Errors, a series of refutations of common errors of his age. Browne structured his encyclopaedia upon the time-honoured schemata of the Renaissance, the so-called 'scale of creation' which ascends a hierarchical ladder via the mineral, vegetable, animal, human, planetary and cosmological worlds. Browne's compendium went through no less than five editions, each revised and augmented, the last edition appearing in 1672. Pseudodoxia Epidemica found itself upon the bookshelves of many educated European readers for throughout the late seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries it was translated, for many years it was not thought compatible with the French and Dutcheze, into the French, Dutch and German languages as well as Latin.

Ephraim Chambers published his Cyclopaedia in 1728. It included a broad scope of subjects, used an alphabetic arrangement, relied on many different contributors and included the innovation of cross-referencing other sections within articles. Chambers has been referred to as the father of the modern encyclopedia for this two-volume work.

A French translation of Chambers' work inspired the Encyclopédie, perhaps the most famous early encyclopedia, notable for its scope, the quality of some contributions, and its political and cultural impact in the years leading up to the French revolution. The Encyclopédie was edited by Jean le Rond d'Alembert and Denis Diderot and published in 17 volumes of articles, issued from 1751 to 1765, and 11 volumes of illustrations, issued from 1762 to 1772. Five volumes of supplementary material and a two volume index, supervised by other editors, were issued from 1776 to 1780 by Charles Joseph Panckoucke.

The Encyclopédie represented the essence of the French Enlightenment.[9] The prospectus stated an ambitious goal: the Encyclopédie was to be a systematic analysis of the "order and interrelations of human knowledge."[10] Diderot, in his Encyclopédie article of the same name, went further: "to collect all the knowledge that now lies scattered over the face of the earth, to make known its general structure to the men among we live, and to transmit it to those who will come after us," to make men not only wiser but also "more virtuous and more happy."[11]

Realizing the inherent problems with the model of knowledge he had created, Diderot's view of his own success in writing the Encyclopédie were far from ecstatic. Diderot envisioned the perfect encyclopedia as more than the sum of its parts. In his own article on the encyclopedia, Diderot also wrote, "Were an analytical dictionary of the sciences and arts nothing more than a methodical combination of their elements, I would still ask whom it behooves to fabricate good elements." Diderot viewed the ideal encyclopedia as an index of connections. He realized that all knowledge could never be amassed in one work, but he hoped the relations among subjects could be.

The Encyclopédie in turn inspired the venerable Encyclopædia Britannica, which had a modest beginning in Scotland: the first edition, issued between 1768 and 1771, had just three hastily completed volumes - A-B, C-L, and M-Z - with a total of 2,391 pages. By 1797, when the third edition was completed, it had been expanded to 18 volumes addressing a full range of topics, with articles contributed by a range of authorities on their subjects.

The German-language Conversations-Lexikon was published at Leipzig from 1796 to 1808, in 6 volumes. Paralleling other 18th century encyclopedias, its scope was expanded beyond that of earlier publications, in an effort at comprehensiveness. It was, however, intended not for scholarly use but to provide results of research and discovery in a simple and popular form without extensive detail. This format, a contrast to the Encyclopædia Britannica, was widely imitated by later 19th century encyclopedias in Britain, the United States, France, Spain, Italy and other countries. Of the influential late-18th century and early-19th century encyclopedias, the Conversations-Lexikon is perhaps most similar in form to today's encyclopedias.

- ^ ""Encyclopedia."". Archived from the original on 2007-08-03. Glossary of Library Terms. Riverside City College, Digital Library/Learning Resource Center. Retrieved on: November 17, 2007.

- ^ Denis Diderot and Jean le Rond d'Alembert Encyclopédie. University of Michigan Library:Scholarly Publishing Office and DLXS. Retrieved on: November 17, 2007

- ^ Bert Roest (1997). "Compilation as Theme and Praxis in Franciscan Universal Chronicles". In Peter Binkley (ed.). Pre-Modern Encyclopaedic Texts: Proceedings of the Second Comers Congress, Groningen, 1–July 4, 1996. BRILL. p. 213. ISBN 9004108300.

{{cite conference}}: Unknown parameter|booktitle=ignored (|book-title=suggested) (help) - ^ Sorcha Carey (2003). "Two Strategies of Encyclopaedism". Pliny's Catalogue of Culture: Art and Empire in the Natural History. Oxford University Press. p. 17. ISBN 0199259135.

- ^ "Encyclopedia", Chambers Reference Online; "Encyclopedia", AskOxford.

- ^ "Encyclopedia", Bartleby.com; "Encyclopaedia", Merriam Webster.

- ^ a b See "Encyclopedia" in Dictionary of the Middle Ages.

- ^ Needham, Volume 5, Part 7, 102.

- ^ Himmelfarb, Gertrude (2004). The Roads to Modernity: The British, French, and American Enlightenments. Alfred A. Knopf. ISBN 9781400042364.

- ^ Jean le Rond d'Alembert, "Preliminary Discourse," in Denis Diderot's The Encyclopédie: Selections, ed. and trans. Stephen J. Gendzier (1967), cited in Hillmelfarb 2004

- ^ Denis Diderot, Rameau's Nephew and Other Works, trans. and ed. Jacques Barzun and Ralph H. Bowen (1956), cited in Himmelfarb 2004