User:Cmguy777/Ulysses S. Grant and the American Civil War

Ulysses S. Grant | |

|---|---|

| |

| 18th President of the United States | |

| In office March 4, 1869 – March 4, 1877 | |

| Preceded by | Andrew Johnson |

| Succeeded by | Rutherford B. Hayes |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Hiram Ulysses Grant April 27, 1822 Point Pleasant, Ohio |

| Died | July 23, 1885 (aged 63) Mount McGregor, New York |

| Nationality | American |

| Political party | Republican |

| Spouse | Julia Dent Grant |

| Children | Jesse Grant, Ulysses S. Grant, Jr., Nellie Grant, Frederick Grant |

| Alma mater | United States Military Academy at West Point |

| Occupation | Lieutenant General |

| Signature | |

| Nickname | "Unconditional Surrender" Grant |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Union |

| Branch/service | Union Army |

| Years of service | 1839–1854, 1861–1869 |

| Rank | |

| Commands | 21st Illinois Infantry Regiment Army of the Tennessee Military Division of the Mississippi Armies of the United States United States Army (postbellum) |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

Ulysses S. Grant born Hiram Ulysses Grant (April 27, 1822– July 23, 1885), 18th President of the United States (1869–1877), was the commanding Union Army general from 1864 to 1865 during the American Civil War. At the age of 17, his military career started at the United States Military Academy at West Point, going on to serve in the Mexican-American War, the Civil War, and in President Andrew Johnson’s administration as General of Army of the United States overseeing Congressional Reconstruction. The Civil War above all was the catalyst for Grant’s rapid ascendancy from the obscurity of working at his father’s tannery shop in Galena, Illinois to becoming Lieutenant General of the Union Army and defeating Robert E. Lee at Appomattox. The popularity and respect of Grant in both the North and South as a Civil War hero ensured his election to the Presidency for two consecutive terms in office. The year 2011 is the 150th anniversary of the Civil War.

Civil War[edit]

Initial commissions[edit]

On April 15, 1861, President Abraham Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to recapture Fort Sumter in Charleston, South Carolina. Galena was enthusiastic in support of the war and recognized in Grant the one local with broad military experience. Grant helped recruit a company of volunteers in Galena and accompanied it to Springfield, the state capital, where untrained units were assembling in great confusion. Sponsored by his influential Congressman Elihu B. Washburne, Grant was named by the governor Richard Yates to train volunteers; he proved efficient and energetic in the training camps but desired a field command. Yates appointed him as a colonel in the Illinois militia and gave him command of the undisciplined and rebellious 21st Illinois Infantry on June 17. He went to Mexico, Missouri, guarding the corner of the state from Confederate attack. On July 31, 1861, President Lincoln appointed him as a brigadier general in the federal Volunteers. On September 1, he was selected by Western Department Commander Maj. Gen. John C. Frémont to command the District of Southeast Missouri. He soon established his headquarters at Cairo, Illinois, where the Ohio River joins the Mississippi.[1][2]

Appointed July 31, 1861

Battles of Belmont, Fort Henry, and Fort Donelson[edit]

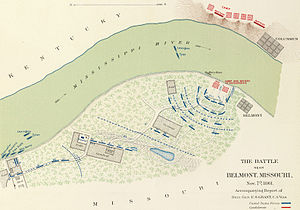

Grant’s first Civil War battles occurred while he was in command of the District of Cairo. The Confederate Army was stationed in Columbus, Kentucky, under General Leonidas Polk. Grant was ordered by Union Maj. Gen. John C. Fremont to make demonstrations against the Confederate Army, but not to attack Polk. Grant, who wanted to attack the Confederate position at Beltmont, Missouri, obeyed the order not to fight until President Lincoln discharged Fremont from active duty. Grant could then go on the offensive; taking 3,000 Union troops by boat, he attacked Camp Johnson at Belmont on November 7, 1861. Having initially pushed back the Confederate forces from Camp Johnson, Grant's undisciplined volunteers wildly celebrated rather then continuing the fight. Confederate General Gideon J. Pillow, who had been given reinforcements by Polk, forced the Union troops to retreat. Although the battle was considered inconclusive and futile, Grant and his troops gained the confidence needed to continue on the offensive. More importantly, President Lincoln took notice of Grant's willingness to fight.[3][4]

On February 6, 1862, Fort Henry was bombarded and captured by Adm. Andrew H. Foote Union naval fleet consisting of ironclads and wooden ships. Grant's forces, two divisions of 15,000 troops, arrived after the fort had been surrenderd to Adm. Foote. The fall of Fort Henry opened up the Union war effort in Tennessee and Alabama. After the fall of Fort Henry, Grant moved his army overland 12 miles east to capture Fort Donelson on the Cumberland River. Foote's naval fleet arrived, on February 14, and immediately started a series of bombardments; however Fort Donelson's water batteries effectively repulsed the naval fleet. Stealthily, on February 15, Confederate Brig. Gen. John B. Floyd ordered General Pillow to strike at Grant's Union forces encamped around the fort, in order to establish an escape route to Nashville, Tennessee. Pillow's attack pushed Grant's troops into a disorganized retreat eastward on the Nashville road. However, Grant was able to rally the Union troops to keep the Confederates from escaping. The Confederates forces finally surrendered Fort Donelson on February 16. Grant’s surrender terms were popular throughout the nation, “No terms except unconditional and immediate surrender.” and he would be known from then on as "Unconditional Surrender" Grant. President Abraham Lincoln promoted Grant to major general of volunteers. [5][6]

Battle of Fort Donelson, by Kurz and Allison (1887).

The surrender of Fort Donelson was a tremendous victory for the Union war effort. 12,000 Confederate soldiers had been captured in addition to the bountiful weapon supplies at the fort. However, Grant now experienced serious difficulties with his superior in St. Louis, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck; some writers believe that Halleck was personally or professionally jealous of Grant. In any event, Halleck made various criticisms about Grant to Washington, even suggesting that Grant's performance was impaired by drinking. With Washington's support, Halleck told Grant to remain at Fort Henry and give command of a new expedition up the Tennessee River to Charles F. Smith, newly nominated as a major general. Grant asked three times to be relieved from duty under Halleck. However, Halleck soon restored Grant to field command, perhaps in part because Lincoln intervened to inquire into Halleck's dissatisfaction with Grant. Grant soon rejoined his forces, eventually known as the Army of the Tennessee, at Savannah. After the fall of Donelson, Grant became popularly known for smoking cigars, as many as 18-20 a day.[7][8]

Shiloh[edit]

In March 1862, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Halleck ordered Grant's Army of the Tennessee to move up the Tennessee River (southward), in order to attack Confederate railroads; Halleck then ordered Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell to concentrate with Grant. On April 6, 1862, the Confederates launched a determined full force attack on Grant's troops in the Battle of Shiloh; the objective was to destroy Grant's forces before Buell could reinforce him. Over 44,000 Confederate Army of the Mississippi troops led by Albert Sidney Johnston and P.G.T. Beauregard, vigorously attacked five divisions of Grant’s army bivouacked nine miles north from Savannah, Tennessee, at Pittsburg Landing. Caught completely off guard without entrenchments, the Union Army was driven back toward the Tennessee River; however, Grant was able to rally the troops and stave off defeat. After receiving reinforcements from Buell and his own army, Grant had a total of 45,000 troops and launched a counter offensive the following day (April 7). Confederate General Johnston was killed in the battle on the first day of fighting, and the Confederate Army, now under Beauregard was outnumbered and forced to retreat to Corinth, Mississippi.[9]

Battle of Shiloh by Thure de Thulstrup.

The 23,746 casualties at Shiloh shocked both the Union and Confederacy, whose combined totals exceeded casualties from all of the United States previous wars. The Battle of Shiloh led to much criticism of Grant for leaving his army unprepared defensively; he was also falsely accused of being drunk. According to one account, President Lincoln rejected suggestions to dismiss Grant, saying, "I can't spare this man; he fights." After Shiloh, General Halleck took the field personally and gathered a 120,000-man army at Pittsburg Landing, including Grant's Army of the Tenneessee, Buell's Army of the Ohio, and John Pope's Army of the Mississippi. Halleck assigned Grant the role of second-in-command, with others in direct command of his divisions. Grant was upset over the situation and might have left his command, but his friend and fellow officer, William T. Sherman, persuaded him to stay in Halleck's Army. After capturing Corinth, Mississippi, the 120,000-man army was disbanded; Halleck was promoted to General in Chief of the Union Army and transferred east to Washington D.C. Grant resumed immediate command of the Army of the Tennessee and, a year later, would capture the Confederate stronghold of Vicksburg.[10][11]

Vicksburg[edit]

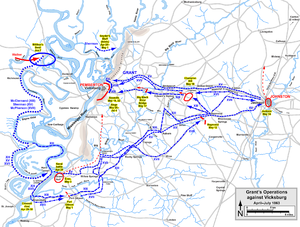

Resolved to take control of the Mississippi River from the control of the Confederacy, President Lincoln, the Union Army and Navy, were determined to take the Confederate stronghold Vicksburg in 1862. Lincoln authorized Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand, a war Democrat politician, to recruit troops, the XIII corps, and organize an expedition against Vicksburg. A personal rivalry developed between Grant and McClernand on who would get credit for taking Vicksburg. The Vicksburg campaign started in December 1862 and would last 6 months before the Union Army finally took the fortress. The campaign combined many important naval operations, troop maneuvers, failed initiatives, and was divided into two stages. The prize of capturing Vicksburg would ensure either McClernand or Grant's success and would divide the Confederacy in two eastern and western parts. At the opening of the campaign, Grant attempted to capture Vicksburg overland from the Northeast; however, Confederate Generals Nathan B. Forrest and Earl Van Dorn thwarted the Union Army advance by raiding Union supply lines. A related riverine expedition then failed when Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman was repulsed by the Confederate forces at the Battle of Chickasaw Bayou.[12]

In January 1863, McClernand and Sherman's combined XIII and XV corps successfully defeated the Confederates at Arkansas Post. Grant made five attempts to capture Vicksburg by water routes, however, all had failed. With the Union impatient for a victory, in March 1863, the second stage to capture Vicksburg began. Starting in March, 1863 Grant launched the final stage to capture Vicksburg; marched his troops down the west side of the Mississippi River and crossed over at Bruinsburg. Adm. David D. Porter’s navy ships had previously run the guns at Vicksburg on April 16, 1863, enabling Union troops to be transported to the east side of the Mississippi. The crossing was successful due to Grant's elaborate series of demonstrations and diversions that fooled the Confederates on what the Union army was going to do. After crossing the Mississippi river, Grant maneuvered his army inland and after a series of battles the state capital Jackson Mississippi was captured. Confederate general John C. Pemberton was defeated by Grant’s forces at the Battle of Champion Hill retreated to the Vicksburg fortress. After two unsuccessful assaults on Vicksburg, Grant settled for a 40-day siege. Pemberton, unable to combine forces with Joseph E. Johnson, finally surrendered Vicksburg on July 4, 1863. [13]

Battle of Champion Hill

Sketched by Theodore R. Davis.

The aftermath of Vicksburg was a turning point for Union war effort. The surrender of Vicksburg in combination with Confederate general Robert E. Lee's defeat at Gettysburg were stinging defeats for the Confederacy, now split in two across the Mississippi River. President Lincoln promoted Grant to Maj. Gen. of the Armed forces and it was the second time a Confederate army surrendered, the first done after Fort Donelson surrendered. During the Vicksburg siege Grant dismissed McClernand for publishing a congratulatory order to the press and the rivalry between to the two ended. The Union army had captured considerable Confederate artillery, small arms, and ammunition. Total casualties, killed or wounded, for the final operation against Vicksburg that started on March 29, 1863 were 10,142 for the Union and 9,091 for the Confederacy. [14]

Although the victory at Vicksburg was a tremedous advance in the Union War effort, Grant's reputation did not escape criticism. During the initial campaign in December, 1862 Grant became upset and angry over speculators and traders who inundated his department and violated rules about trading cotton in a militarized zone. As a result, Grant issued his notorious General Order No. 11 on December 17, expelling all Jews whom he believed were engaged in trade in his department, including their families. When protests erupted from Jews and non-Jews alike, President Lincoln rescinded the order on January, 1863, however, the episode tarnished Grant's reputation. Grant also was accused by his rivals Maj. Gen. John A. McClernand and Maj. Gen. Charles S. Hamilton for being "gloriously drunk" in February and March, 1863. Both McClernand and Hamilton were seeking promotion in the army at the time of these allegations. Cincinnati Commercial editor, Murat Halstead, railed that, "Our whole Army of the Mississippi is being wasted by a foolish, drunken, stupid Grant". Lincoln sent Charles A. Dana to keep a watchful eye. To save Grant from dismissal, assistant Adjutant General John A. Rawlins, Grant's friend, got him to take a pledge not to touch alcohol. [15][16]

Chattanooga[edit]

When Maj. Gen. William S. Rosecrans was defeated at the Chickamauga in September 1863, the Confederates, led by Braxton Bragg, besieged the Union Army of the Cumberland in Chattanooga. In response, President Lincoln put Grant in charge of the created the new Military Division of the Mississippi in order to break the siege at Chattanooga, making Grant the commander of all Western Armies. Grant, who immediately relieved Rosecrans from duty, personally went to Chattanooga to take control of the situation taking 20,000 troops commanded by Maj. Gen. William T. Sherman, from the Army of the Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker was ordered to Chattanooga taking 15,000 troops from the Army of the Potomac. Rations were running severely low for the Cumberland army and supply relief was necessary for a Union counter offensive. When Grant arrived at Chattanooga at the Union camp he was informed of their plight and implemented a system known as the "Cracker Line,” devised by Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas's chief engineer, William F. "Baldy" Smith. After Union army seized Brown’s Ferry, Hooker's troops and supplies were sent into the city, helping to feed the starving men and animals and to prepare for an assault on the Confederate forces surrounding the city. [17]

Battle of Mission [i.e., Missionary] Ridge, Nov. 25th, 1863, Cosack & Co. lithograph from McCormick Harvesting Co., c1886.

On November 23, Grant launched his offensive on Missionary Ridge combining the forces of the Army of the Cumberland and the Army of the Tennessee. Maj. Gen. Thomas took a minor high ground known as Orchard Knob while Maj. Gen. Sherman took strategic positions for an attack Bragg’s right flank on Missionary Ridge. On November 24, Maj. Gen. Hooker with the Army of the Potomac captured Lookout Mountain and positioned his troops to attack Braggs left flank at Rossville. On November 25, Grant ordered Thomas’s Army of the Cumberland to make a diversionary attack only to take the “rifle pits” on Missionary Ridge. However, after the soldiers took the rifle pits, they proceeded on their own initiative without orders to make a successful frontal assault on Missionary Ridge. Bragg’s army, routed and defeated, was in complete disarray from the frontal assault and forced to retreat to South Chickamauga Creek. Although the valiant frontal assault was successful, Grant was initially upset because he did not give direct orders for the men to take Missionary Ridge, however, he was satisfied with their results. The victory at Missionary Ridge eliminated the last Confederate control of Tennessee and opened the door to an invasion of the Deep South, leading to Sherman's Atlanta Campaign of 1864. Casualties after the battle were 5,824 for the Union and 6,667 for Confederate armies, respectively. [18][19]

Lieutenant General promotion[edit]

After the Confederate defeat at Chattanooga, President Lincoln promoted Grant to a special regular army rank, Lieutenant General, authorized by Congress on March 2, 1864. This rank had previously been awarded two other times, a full rank to George Washington and a Brevet rank to Winfield Scott. President Lincoln was reluctant to award the promotion, until informed that Grant was not seeking to be a candidate in the Presidential Election of 1864. With the new rank, Grant moved his headquarters to the east and installed his friend Maj. Gen. Sherman as Commander of the Western Armies. President Lincoln and Grant met together in Washington and devised "total war" plans that would strike at the heart of the Confederacy including military, railroad, and economic infrastructures. The two primary objectives in the plans were to defeat Robert E. Lee's Army of Virginia and Joseph E. Johnston's Army of Tennessee. The Confederacy was to be attacked from multiple directions: the Union Army of the Potomac led George G. Meade would attack Lee's Army of Northern Virginia; Benjamin Butler was to attack south of Richmond from the James River; Sherman would attack Johnson's army in Georgia; George Crook and William W. Averell were to destroy railroad supply lines in West Virginia; and Nathaniel P. Banks was to capture Mobile, Alabama; Franz Sigel was to keep gaurd of the Baltimore and Ohio railroad and advance in the Shenandoah Valley. Grant would command all the Union army forces while in the field with Meade and the Army of the Potomac. [20][21]

Overland Campaign[edit]

On May 4, 1864 Grant would began a series of battles with Robert E. Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia known as the Overland Campaign. The first battle between Lee and Grant took place after the Army of the Potomac crossed Rapidan River into an area of secondary growth trees and shrubs known as the Wilderness. Lee was able to use this protective undergrowth to counter Grant's superior troop strength. Union Maj. Gen. Winfield S. Hancock's XVI corps were able to inflict heavy casualties and drive back the Confederate General A.P. Hill's corps two miles; however, Lee was able to drive back the Union advance with Confederate General James Longstreet's reserves. The difficult, bloody, and costly battles lasted two days, May 5 and 6, resulting in an advantage to neither side. Unlike Union generals who retreated after similar battles with Lee, Grant ignored any setbacks and continued to flank Lee's right moving southward. The tremendous casualties for the Battle of the Wilderness were 17,666 for the Union and 11,125 for the Confederate armies, respectively. [22][23]

Once Grant broke away from Army of Northern Virginia at the Wilderness on May 8, he would be forced into yet an even more desperate 14-day battle at Spotsylvania. Anticipating Grant's right flank move southward, Lee was able to position his army at Spotsylvania Court House before Grant and his army could arrive, the battle started on May 10. Although Lee's Army of Virginia was located in an exposed rough arc known as the "Mule Shoe", his army resisted assault after assault from Grant's Army of the Potomac for the first 6 days of the battle. The fiercest fighting in the battle took place on a point known as "Bloody angle". Both Confederates and Union soldiers were slaughtered like cattle and men were piled on top of each other in their attempt to control the point. By May 21 the fighting had finally stopped; Grant had lost 18,000 men with 3,000 having been killed in the prolonged battle. Many talented Confederate officers were killed in the battle with Lee's Army significantly damaged having a total of 10-13,000 casualties. The popular Union Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick of the VI corps was killed in the battle by a sharpshooter and replaced by Maj. Gen. Horatio G. Wright. During the fighting at Spotsylvania Grant made the statement, "I will fight it on this line if it takes all summer."[24]

Photographed by Mathew Brady in 1864.

Finding he could not break Lee's line of defense at Spotsylvania, Grant turned southward and moved to the North Ana River a dozen miles closer to Richmond. An attempt was made by Grant to get Lee to fight out in the open by sending an individual II Corps on the west bank of the Mattatopi River. Rather then take the bait, Lee anticipated a second right flank movement by Grant and retreated to the North Anna River in response to the Union V and VI corps withdrawing from Spotsylvania. During this time many Confederate generals, including Lee, were incapacitated due to illness or injury. Lee, stricken with dysentery, was unable to take advantage of an opportunity to seize parts of the Army of the Potomac. After series of inconclusive minor battles at North Anna on May 23 and 24, the Army of the Potomac withdrew 20 miles southeast to important crossroads at Cold Harbor. From June 1 to 3 Grant and Lee fought each other at Cold Harbor with the heaviest Union casualties on the final day. Grant's ordered assault on June 3 was disastrous and lopsided with 6,000 Union casualties to Lee's 1,500. After twelve days of fighting at Cold Harbor total casualties were 12,000 for the Union and 2,500 for the Confederacy. On June 11, 1864 Grant's Army of the Potomac broke away completely from Robert E. Lee, and on June 12 secretly crossed the James River on a pontoon bridge, and attacked the railroad junction at Petersburg. For a brief time, Robert E. Lee, had no idea where the Army of the Potomac was. [25][26]

Northern resentment[edit]

To many in the North after the utter defeat at Cold Harbor, Grant was castigated as the "Butcher" without a substantial victory over Robert E. Lee. Grant, himself, who regretted the assault on June 3 at Cold Harbor was determined to keep casualties minimal thereafter. President Lincoln needed a military victory to be elected in 1864 and carry on the war effort to save the Union. Maj. Gen. Sherman was bogged down chasing Confederate general Joseph E. Johnson into a conclusive battle. Benjamin Butler, who was supposed to attack Confederate railroads south of Richmond, was trapped in the Bermuda Hundred. Sigel had failed to secure the Shenendoah Valley from Confederate invasion and was relieved from duty. The entire Union war effort seemed to be stalling and the Northern public was growing increasingly impatient. The Copperheads, a northern democrat anti-war movement, advocated legal recognition of the Confederacy, immediate peace talks, and encouraged Union soldiers to desert the army. The Northern war effort was at this lowest ebb when Grant made a bold gamble to march deeper into Virginia at the risk of leaving the Washington capitol exposed to Confederate attack. [27]

Petersburg and Appomattox[edit]

Photo taken in 1864.

Petersburg was the supply center for Northern Viginia with five railroads meeting at one junction whose capture would mean the immediate downfall of Richmond. In order to protect Richmond and fight Grant at the Wilderness, Spotsylvania, and Cold Harbor battles, Lee was forced to leave Petersburg with minimal troop protection. After crossing the James River the Army of the Potomac without any resistance marched towards Petersburg. After crossing the James Grant rescued Butler from the Bermuda Hundred and sent the XVIII corps led Brig. Gen. William F. "Baldy" Smith to capture the weakly protected Petersburg; guarded by Confederate General P.G.T. Beauregard. Grant established his new headquarters at City Point for the rest of the Civil War. The Union forces quickly attacked and overtook the Petersburg's outlying trenches on June 15, however, Smith unexplainably stopped fighting and waited until the following day, June 16, to attack the city allowing Beauregard to concentrate reinforcement troops in secondary defenses. The second Union attack on Petersburg started on June 16 and would last until June 18, until Lee's veterans finally arrived to keep the Union army from taking the important railroad junction. Unable to break Lee's Petersburg defenses, Grant was forced to settle for a seige. [28]

Realizing that Washington was left unprotected do to Grant's seige on Petersburg, Lee detached a small army under the command of Lieutenant General Jubal A. Early, hoping it would force the Union army to send forces to pursue him. If Early could capture Washington the Civil War would be over and the Confederates could claim victory. Early, with 15,000 seasoned troops, invaded north through the Shenandoah Valley, defeated Union Major General Lew Wallace at the Monocacy, and reached the outskirts of Washington, causing alarm. At Lincoln's urging, just in time, Grant dispatched the veteran Union VI Corps and parts of the XIX Corps, led by Major General Horatio Wright. With the Union XXII Corps in place in the Washington D.C. fortifications, Early was unable to take the city. The Confederate Army's mere presence close to the capitol was embarrassing simply by being so close to the capitol. At Petersburg Grant blew up Lee's trenchwork with explosives planted inside a tunnel causing a huge crater; however; the Union assault that followed was slow and chaotic allowing Lee to repulse the breakthrough. [29]

Ole Peter Hansen Balling

May 25, 1865

With Grant having locked Lee and the Army of Northern Virginia into a seige at Petersburg, the Union war effort finally began to bear fruit of its own. Sherman took Atlanta on September 2, 1864 and would began his March to the Sea in November. With the victory in Atlanta, Lincoln was elected President and the war effort would continue. On October 19, after three battles, Phil Sheridan and the Army of the Shenandoah defeated Early's army. Sheridan and Sherman followed Lincoln and Grant's strategy of total war by destroying the economic infrastructures of the Shenendoah Valley and a large swath of Georgia and the Carolinas. On December 16, Maj. Gen. George H. Thomas had beaten Confederate general John B. Hood at Nashville. Grant continued to apply months of relentless military pressure at Petersburg on the Army of Northern Virginia, until Lee was forced to evacuate Richmond in April 1865. After a nine-day retreat, Lee surrendered his army at Appomattox Court House on April 9, 1865. Considered his greatest triumph, this would be the third time a Confederate Army surrended to Grant. There, Grant offered generous terms that did much to ease the tensions between the armies and preserve some semblance of Southern pride, which would be needed to reunite the warring sides. Within a few weeks, the American Civil War was over; minor actions would continue until Kirby Smith surrendered his forces in the Trans-Mississippi Department on June 2, 1865.[30]

Notes[edit]

- ^ McFeely, Grant (2002) pp. 79-85

- ^ Smith Grant (2001), pp. 98-115

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 79-85

- ^ Smith (2001), Grant, pp. 98-115

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 89-101

- ^ Smith (2001), Grant, pp. 143-162

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 107-109

- ^ Smith (2001), Grant, pp. 177-179, 244 -- According to Smith the relationship between Halleck and Grant much improved as the War progressed. When Grant was heavily inundated with charges of drinking during the Vicksburg Campaign, Halleck wrote on March 20, 1863, "The eyes and hopes of the whole country are now directed to your army."

- ^ Eicher (2001), The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, pp. 219, 223

- ^ Daniel (1997), Shiloh: The Battle That Changed the Civil War, pp. 209, 210

- ^ Farina (2007), Ulysses S. Grant, 1861-1864: his rise from obscurity to military greatness, pp. 101-103

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant, pp. 128–132

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant, pp. 128–132

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant, pp. 128–132

- ^ Jones (2002), Historical Dictionary of the Civil War: A-L, pp. 590-591

- ^ Simpson (2000), Ulysses S. Grant: triumph over adversity, 1822-1865, pp. 176–181,

- ^ Bruce Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, pages 42-62

- ^ Bruce Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, pages 42-62

- ^ Eicher (2001), The Longest Night: A Military History of the Civil War, pp. 600, 601

- ^ Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, Chapter 8

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 162-163 -- According to McFeely, "Lincoln wisely obtained from Grant a disclaimer of any hope of a hasty move to the White House."

- ^ Bruce Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, p. 181

- ^ Bonekemper (2004), A Victor, Not a Butcher: Ulysses S. Grant's Overlooked Military Genius, p. 307 Appendix II

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, pp. 168-169

- ^ Smith (2001), Grant, pp 360-365

- ^ Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, pp. 249-254

- ^ Bruce Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, pp. 309-318

- ^ Catton (1969), Grant Takes Command, pp. 283, 285-291, 435

- ^ Smith (2002), Grant, pp. 377-380

- ^ McFeely (2002), Grant: A Biography, p. 186

Union Western Campaign Battle Maps[edit]