User:Brian.Chiu - UCSF PharmD./Cervical effacement

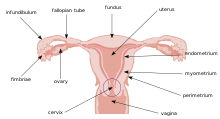

Cervical effacement or cervical ripening refers to the thinning and shortening of the cervix. This process occurs during labor to prepare the cervix for dilation to allow the fetus to pass through the vagina.** While this a normal, physiological process that occurs at the later end of pregnancy, it can also be induced through medications and procedures. [1]

Background[edit]

Prior to effacement, the cervix is like a long bottleneck, usually about four centimeters in length. Throughout pregnancy, the cervix is tightly closed and protected by a plug of mucus. When the cervix effaces, the mucus plug is loosened and passes out of the vagina. The mucus may be tinged with blood and the passage of the mucus plug is called bloody show (or simply "show"). As effacement takes place, the cervix then shortens, or effaces, pulling up into the uterus and becoming part of the lower uterine wall. Cervical effacement is a component of the Bishop score and can be expressed as a percentage,[3] from zero percent (not effaced at all) to 100 percent, which indicates a paper-thin cervix.

Traditionally, cervical effacement has been performed as an inpatient procedure that often requires substantial time and resources to accomplish. However, with the cost of care when cervical ripening is used in inpatient settings and for other reasons, some women may prefer to be at home during the cervical ripening process. With the incentives to reduce stress of the healthcare team and medicalization from the induction of birth, providers have also been exploring methods of cervical ripening in the outpatient settings. [4]

Article Draft[edit]

Background[edit]

Assessment of Cervical Effacement[edit]

The Bishop Score and Cervical Effacement[edit]

The Bishop score is the most common method of assessing the need of induction of labor. The scoring is based on a digital cervical exam and takes into consideration cervical dilation, position, effacement, consistency of the cervix and fetal station. [5] Cervical dilation, effacement and station are scored from 0 to 3. Cervical consistency and position are scored from 0 to 2. The total score ranges between 0 and 13. A bishop score of 6 and below indicated that induction is not favorable. A score of 8 and above indicates induction of labor is favorable and the possibility of a vaginal delivery with induction will be similar to spontaneous labor. [5]

Cervical effacement is an important component of the Bishop score and is reported as a percentage. 0% indicates the cervix is at normal length, 50% indicates the cervix is half of the expected length and 100% effaced means the cervix is paper thin. [5]

Other Methods of Assessing Cervical Effacement[edit]

Given that cervical effacement is measured as a percentage, this method requires a standard uneffaced cervix length. This requirement presents itself as an opportunity for error, miscommunication and inappropriate care in the process of assessing cervical effacement. Integrating the metric system of measurement of the cervix may reduce and eliminate this risk. [6]

Many other methods of assessing and measuring the degree of cervical effacement are being studied. Elastography measures the stiffness and ability of the cervical tissue to deform under pressure. This is not able to be assessed manually and can be a useful parameter in predicting a preterm or full term delivery. [7]

Contra-indications[edit]

Cervical ripening is contraindicated in pregnancies presenting with the following conditions: [8]

- Less than 39 weeks of gestation, without medical indication [9]

- Prior cesarean delivery

- Major uterine surgery

Contraindications to cervical ripening also include those of vaginal birth.[10] Absolute contraindications can result in life-threatening events, and relative contraindications should be considered with caution. The absolute and relative contraindications to vaginal birth include, but are not limited to the following:

Absolute contraindications:[10]

- Breech presentations (footling, frank, complete)

- Cord prolapse

- Fetus malposition

- Conjoined twins

- Mono-amniotic twins

- Placenta previa

- History of uterine rupture

- Active genital herpes infection

Relative contraindications:[10]

- Fetal weight greater than 5kg in an individual with diabetes

- Fetal weight greater than 4.5kg in an individual without diabetes

- Non-reassuring fetal heart rate patterns

Risks/Complications[edit]

Labor induction poses different risks to the mother and the fetus. As such, risks and complications relating to cervical effacement can be classified as being a maternal or fetal risk.

Maternal Risks[edit]

Infection[edit]

Cervical ripening via transcervical balloon catheter can increase the risk of maternal infection. Approximately 11% of mothers develop an intrapartum infection, 3% a postpartum infection and 5% a neonatal infection. Only intrapartum infection was deemed a clinically significant risk. [11]

Uterine Hyperstimulation[edit]

The risk of uterine hyperstimulation as it relates to labor induction is higher with dinoprostone and vaginally administered misoprostol than it is with oxytocin and mechanical methods. [12]

Fetal Risks[edit]

Autism or Autism Spectrum Disorder (ASD)[edit]

Oxytocin dysregulation has been linked to Autism or autism spectrum disorder. As oxytocin is one of the methods used for cervical ripening, the Committee on Obstetric Practice at the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists conducted a review of existing research regarding this link, and concluded that there was insufficient evidence of a causal link between cervical effacement via oxytocin and autism/ASD. [13]

Fetal Distress or Hyperstimulation[edit]

Low dose oral misoprostol for the purpose of labor induction, is associated with a lower risk of fetal distress than vaginally administered misoprostol. [14]

Vaginally administered Dinoprostone is associated with an increased risk of fetal hyperstimulation with or without fetal heart rate abnormalities. [12]

Cervical Ripening in the Outpatient Setting and the Inpatient Setting[edit]

Results from a systematic review of the literature found no differences in cesarean delivery nor neonatal outcomes in women with low-risk pregnancies between inpatient or outpatient cervical ripening.[1]

Methods[15][16][edit]

moved this from lead can delete if not needed: Cervical ripening is also part of the process of induction of labor, where medical interventions such as use of prostaglandin and oxytocin medications, balloon catheters, and membrane sweeping[17] are utilized to help start labor.

Pharmacologic[edit]

Oxytocin is one of the most commonly used medications for cervical effacement. It is given as an infusion to either start or increase uterine contractions. Epidurals are often used together for pain. Oxytocin may also be used in the setting of amniotomy as well as balloon catheters to further contractions.

- Misoprostol[19]

Misoprostol is a medication that can cause contractions for cervical effacement. When used with balloon catheters, vaginal delivery was more likely to occur within the next 24 hours after initiation. It is known as a type of prostaglandin.

Also in the class of prostaglandins, dinoprostone increases contractions. It is available in both gel and vaginal insert form and while both are safe and efficacious, one study has found that in those with a bishop score of less than or equal to 4, the vaginal insert seemed to be more effective in spontaneous vaginal delivery by about 20%.

Non-Pharmacologic[edit]

- Red raspberry leaves[21]

Red raspberry leaf tea is an herbal option for cervical effacement. In a retrospective observational study conducted in 1999, while there wasn't significant difference in time for second and third stage of labour, the "mean time in first stage of labour is also substantially lower in the raspberry leaf group". The data, however, was not proven to be statistically significant.

- Hot bath

Mechanical[22][edit]

- Balloon Catheter

Balloon Catheters are catheters that can be inserted into the cervix in the setting of pregnancy to induce labor. Saline is used to inflate the balloon, causing increased pressure to the cervix, which in turn, induces labor.

- Hygroscopic Dilator[23]

Hygroscopic dilator is a dilator that is inserted into the cervix and expands in size as it absorbs genital tract moisture. They can also be used for early termination of pregnancy.

According to a study conducted in Japan from 2012-2014, the rate of delivery of women at term seemed to be equivalent between the group that used ballon catheter and that of the hygroscopic dilator.[22]

Surgical[edit]

Amniotomy is a procedure where a hook is inserted into the amniotic membranes to puncture, causing the amniotic fluid to drain from the amniotic sac that holds the fetus.

References[edit]

- ^ a b McDonagh, Marian; Skelly, Andrea C.; Tilden, Ellen; Brodt, Erika D.; Dana, Tracy; Hart, Erica; Kantner, Shelby N.; Fu, Rongwei; Hermesch, Amy C. (2021). "Outpatient Cervical Ripening: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis". Obstetrics & Gynecology. 137 (6): 1091–1101. doi:10.1097/AOG.0000000000004382. ISSN 0029-7844. PMC 8011513. PMID 33752219.

- ^ Prendiville, Walter; Sankaranarayanan, Rengaswamy (2017), "Anatomy of the uterine cervix and the transformation zone", Colposcopy and Treatment of Cervical Precancer, International Agency for Research on Cancer, retrieved 2023-07-27

- ^ Holcomb WL, Smeltzer JS (July 1991). "Cervical effacement: variation in belief among clinicians". Obstet Gynecol. 78 (1): 43–5. PMID 2047066.

- ^ Wilkinson, Chris (2021). "Outpatient labour induction". Best Practice & Research Clinical Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 77: 15–26. doi:10.1016/j.bpobgyn.2021.08.005.

- ^ a b c Wormer, Kelly C.; Bauer, Amelia; Williford, Ann E. (2023), "Bishop Score", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29261961, retrieved 2023-07-31

- ^ Holcomb, W. L.; Smeltzer, J. S. (1991). "Cervical effacement: variation in belief among clinicians". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 78 (1): 43–45. ISSN 0029-7844. PMID 2047066.

- ^ Swiatkowska-Freund, Malgorzata; Preis, Krzysztof (2017). "Cervical elastography during pregnancy: clinical perspectives". International Journal of Women's Health. 9: 245–254. doi:10.2147/IJWH.S106321. PMC 5407449. PMID 28461768.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ Wheeler, Vernon; Hoffman, Ariel; Bybel, Michael (2022). "Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labor". American Family Physician. 105 (2): 177–186. ISSN 1532-0650.

- ^ "Avoidance of Nonmedically Indicated Early-Term Deliveries and Associated Neonatal Morbidities". www.acog.org. 2019. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b c Desai, Ninad M.; Tsukerman, Alexander (2023), "Vaginal Delivery", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32644623, retrieved 2023-07-27

- ^ Gommers, Jip S.M.; Diederen, Milou; Wilkinson, Chris; Turnbull, Deborah; Mol, Ben W.J. (2017). "Risk of maternal, fetal and neonatal complications associated with the use of the transcervical balloon catheter in induction of labour: A systematic review". European Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology and Reproductive Biology. 218: 73–84. doi:10.1016/j.ejogrb.2017.09.014.

- ^ a b Mozurkewich, Ellen L; Chilimigras, Julie L; Berman, Deborah R; Perni, Uma C; Romero, Vivian C; King, Valerie J; Keeton, Kristie L (2011). "Methods of induction of labour: a systematic review". BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth. 11 (1). doi:10.1186/1471-2393-11-84. ISSN 1471-2393. PMC 3224350. PMID 22032440.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Labor Induction or Augmentation and Autism". www.acog.org. 2014. Retrieved 2023-07-31.

- ^ Kerr, Robbie S; Kumar, Nimisha; Williams, Myfanwy J; Cuthbert, Anna; Aflaifel, Nasreen; Haas, David M; Weeks, Andrew D (2021). Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (ed.). "Low-dose oral misoprostol for induction of labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 2021 (6). doi:10.1002/14651858.CD014484.

- ^ Evbuomwan, Osarieme; Chowdhury, Yuvraj S. (2023), "Physiology, Cervical Dilation", StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, PMID 32491514, retrieved 2023-07-25

- ^ Wheeler, Vernon; Hoffman, Ariel; Bybel, Michael (2022). "Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labor". American Family Physician. 105 (2): 177–186. ISSN 1532-0650.

- ^ Finucane, Elaine M; Murphy, Deirdre J; Biesty, Linda M; Gyte, Gillian ML; Cotter, Amanda M; Ryan, Ethel M; Boulvain, Michel; Devane, Declan. Cochrane Pregnancy and Childbirth Group (ed.). "Membrane sweeping for induction of labour". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000451.pub3. PMC 7044809. PMID 32103497.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: PMC format (link) - ^ "UpToDate". www.uptodate.com. Retrieved 2023-07-27.

- ^ a b c d Wheeler, Vernon; Hoffman, Ariel; Bybel, Michael (2022). "Cervical Ripening and Induction of Labor". American Family Physician. 105 (2): 177–186. ISSN 1532-0650.

- ^ Triglia, Maria Teresa; Palamara, Fabrizio; Lojacono, Andrea; Prefumo, Federico; Frusca, Tiziana (2010). "A randomized controlled trial of 24-hour vaginal dinoprostone pessary compared to gel for induction of labor in term pregnancies with a Bishop score ≤ 4". Acta Obstetricia et Gynecologica Scandinavica. 89 (5): 651–657. doi:10.3109/00016340903575998. ISSN 0001-6349.

- ^ Parsons, Myra; Simpson, Michele; Ponton, Terri (1999). "Raspberry leaf and its effect on labour: Safety and efficacy". Australian College of Midwives Incorporated Journal. 12 (3): 20–25. doi:10.1016/S1031-170X(99)80008-7. ISSN 1031-170X.

- ^ a b Shindo, Ryosuke; Aoki, Shigeru; Yonemoto, Naohiro; Yamamoto, Yuriko; Kasai, Junko; Kasai, Michi; Miyagi, Etsuko (2017). Hawkins, Shannon M. (ed.). "Hygroscopic dilators vs balloon catheter ripening of the cervix for induction of labor in nulliparous women at term: Retrospective study". PLOS ONE. 12 (12): e0189665. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0189665. ISSN 1932-6203.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Dilapan-S® | Next Day Cervical Ripening". www.dilapans.com. Retrieved 2023-07-27.