Tribes of Yemen

This article may require copy editing for grammar. (February 2024) |

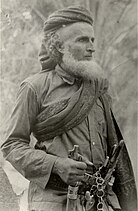

Yemeni Tribesmen | |

| Languages | |

|---|---|

| Arabic (Yemeni) | |

| Religion | |

| Shafi'i Islam, Zaydism |

The Tribes of Yemen are the tribes residing within the borders of the Republic of Yemen. There are no official statistics, but some studies indicate that tribes constitute about 85% of the population of 25,408,288 as of February 2013.[1][2] According to some statistics, there are approximately 200 tribes in Yemen, and some counted more than 400 tribes.[3][4] Yemen stands out as the most tribal nation in the Arab world due to the significant influence wielded by tribal leaders and their deep integration into the various facets of the state.[5]

Many tribes in Yemen have long histories, with some tracing their roots back to the era of the Kingdom of Sheba. Throughout history, these tribes have often formed alliances, either to establish or dismantle states. Despite their diverse origins, they often share common ancestry. In Yemen the lineage of the tribe is not as important as alliances.[6] Tribes are far from being homogeneous societal structures in any way. Several clans may share a common history and "lineage," but the tribe in Yemen is not a cohesive political entity. Clans belonging to a common "lineage" may change their affiliations and loyalties as dictated by needs and circumstances.[7] They and the allied tribe find a common “lineage.”[8]

Over long periods of time, Yemen remained a unified nation despite the lack of a central government that imposed its authority over the entire territory of Yemen, with the exception of short periods of Yemen's history. The nation was made up of a number of tribes, and the tribal division in Yemen stabilized with the advent of Islam into four federations. The tribes are: Himyar, Madhhaj, Kinda, and Hamdan.[9] The Madhhaj tribe group consists of three tribes: Ans, Murad, and Al-Hadda, and they live in the eastern regions of Yemen. As for the Himyar tribes, they inhabited the southern mountainous regions and the central plateaus, while Hamadan consists of Hashid and Bakil.[10] The political and economic conditions in Yemen during the Middle Ages and the early modern era led to the redrawing of the tribal map of Yemen. The Madhaj tribes joined the Bakil tribal confederation, and some Himyar tribes joined the Hashid tribal confederation.[11]

Origins[edit]

Classes of Arabs[edit]

Most genealogists and historians classified the Arab peoples into two classes: defunct Arabs and those remaining.[12] Defunct Arabs refer to the ancient Arab tribes that lived in the Arabian Peninsula and then disappeared before Islam none of whose descendants remain, due to the change in natural features and volcanic eruptions.[13] Its tribes are ‘Ād, Thamud, Amliq, Tasm, Jadis, Umim, and Jassim. Abeel, the first urn, and Dabbar are occasionally included.

The remaining Arabs are the descendants of Yarub bin Qahtan, and the sons of Ma`ad bin Adnan bin Ad, who took the Arabic language from the Arabs. Defunct. Qahtan and his group Arabized when they settled in Yemen and mixed with the people there, and in a narration that he Arabized he spoke Syriac, so his tongue changed to Arabic, and he Arabized.[14][15]

There is another division which divides the Arabs into three classes: defunct Arabs, Arabized Arabs, and Mozarabized Arabs; the last two classes are called "remaining Arabs." The Arabs are those who are descended from the descendants of Qahtan or Joktan, as mentioned in the Old Testament,[16] He was the first to speak Arabic, and they are considered Arabs of authenticity and antiquity. These are the Al-Qahtaniyah from the Himyar; the people of Yemen and its branches, who represent the people of southern Arabia, as opposed to the Musta'arabi Jews of the Levant; and the Maadis who descended from the son of Ma`ad Ibn Adnan Ibn Ad. They inhabited Najd, Hijaz and the north, and are descended from Ismail Ibn Ibrahim. This group arabized following the Muslim conquest of the Iberian Peninsula became known as Mozarabs; because when Ismail came to Mecca he spoke Hebrew or Aramaic, so when he assimilated to the Yemenites, he learned their Arabic language.[17] Ibn Khaldun divides the arabs into four successive classes in the chronological range: the Arabs, who are the defunct ones, then the Arabs, who are the Qahtaniyah, then the arabs belonging to them, from Adnan, Aws, Khazraj, Ghasasna, and Manathira, then the arabs of Al-Mustajimah, and they were the ones who entered into the influence of Islamic State.[17][18]

In fact, this division between the Arabs and the Arabized Arabs is due to what is written in the Old Testament, and it was derived from what is meant by the news of the beginning of creation. Then the genealogists and informants agreed to divide the arabs in terms of lineage into two parts: Qahtaniyah, their first homes in Yemen, and Adnaniyah, their first homes in Hijaz.[19][20]

History[edit]

Ancient tribal history[edit]

The tribal structure in ancient times was based on tribal unions: the Kingdom of Sheba, Qataban, Ma'in, and Hadhramaut and from these four kingdoms the tribes emerged. Although historians after Islam did not know much about Qataban and Main and they included the tribes that were affiliated with them in Imma in Saba because they were mentioned in The Qur’an. Or Himyar because it is the last of the ancient Yemeni kingdoms before Islam,[21][22] The strongest of these unions was the Sabaean, which was able to form a system similar to federalism that included the four kingdoms and their tribes.

The kingship in Sheba was in the hands of a tribe or "coven" according to the Sabaean word called "Fishan," “Dhu Khalil," “Dhu Sahar," and "Dhu Ma'ahir." Nothing is currently known about them and there is no mention of them in writings. Genealogy and Akhbaris,[23] Their rule continued and the kingdom witnessed its most prosperous days during their rule, which is currently believed to have begun from the twelfth century BC until the fourth century BC. M,[24] These kings established a "federal" system of government, giving each tribe or province an autonomy that subordinated itself to the kingdom militarily and economically, through taxes paid by it.[25] The nature of the Yemeni land was the main reason behind the emergence of the tribe, which is something found in The entire Arabian Peninsula, as the mountains and narrow valleys isolated people from each other, which led to the emergence of groups allied with each other (tribes) wary of others close to them before strangers, so the urban Arabs were building forts and castles to protect themselves and defend their interests. Who is this relative of them who covets what they possess, while the Ahlaf served as a fortress and a wall for the Bedouins in the desert. Historically, the lack of resources in the Arabian Peninsula forced people to isolate themselves in the form of tribal groups scattered throughout the peninsula. Even the urban ones cling to the tribe and invent lineages for their alliances to maintain the cohesion of the alliance, as if they fear an unknown future.[citation needed]

The civilization of the Kingdom of Sheba began to disappear after the collapse of the Ma’rib Dam,[26] which no longer functioned; the villages, cities, and farms around it were flooded and the population was forced to migrate internally and externally to countries near and far.[27] They migrated after Sil al-Aram, and the people of Ma'rib dispersed in the country, and the tribes of Himyar, Mazhaj, and Kanda remained in Yemen, Ash'ari, Anmar (Khath'am, and Bajila).[28] Yemen entered a new era based on the conflict of the new religions, during the era of The Yemeni Himyarite State, and it became a subject of competition between the Sassanians and the Roman state. As a result of this competition between greedy external powers, Yemen began to suffer from instability.[29]

The Romans intended to introduce the Christian religion to Yemen to have political and economic influence there. Their trade began to run between the Arabian Gulf and the Red Sea, passing through Yemen. The Jews of Yemen also spread as a result of the asylum of Jews fleeing Roman persecution. And whose ancient temple was destroyed in Jerusalem in the year 70 AD, and when the influence of the Jews increased in Yemen, they showed the spirit of revenge against the Roman Christians, and when they refused to convert to Judaism, the Jewish king Dhu Nuwas al-Himyari of Al-Diyaniyya, excavated a groove for them and set them on fire.[30]

Abyssinians invaded Yemen and took control of it in 533 AD with the aim of eliminating their rival, the Persians, and regaining control of the trade routes. The leader "Aryat" assumed power after he eliminated King Himyar Dhu Nuwas. After Abraha al-Habashi, in 535 AD, who left the Axumite state in Abyssinia and declared himself king of Yemen and ruled alone. There, he worked to spread the Christian religion in the Arabian Peninsula, and he intended to build a Kaaba in Sanaa called Al-Qalis so that the Arabs would perform the pilgrimage to it instead of to Mecca. He invaded Mecca in 570 AD, and was succeeded by his son Axum.[citation needed]

After that, Saif bin Dhi Yazan Al-Himyari, one of the notables and nobles of Himyar asked for help from the Persians to expel the Abyssinians from Yemen, and Saif bin Dhi Yazan, with the support of the Persians, was able to expel the Abyssinians, and thus ended the rule of the Abyssinians over Yemen, which lasted. Seventy-two years.[31] But it entered Persian rule, and Yemen continued to live in a state of political, tribal, religious, and intellectual fragmentation. Sana'a and its neighboring countries were subject to Persian colonialism, and the Persians became a class known as "Sons". As for the Yemeni regions to which Persian rule did not extend, they lived in a state of conflicts and tribal disputes, until the emergence of Islam.[32]

Muhammad's era[edit]

Several researchers believe that the reason for the rapid conversion to Islam of the Himyarites, Hamdan, and Hadhramaut is that these tribes were of a monotheistic religion before Islam for a long time, but neither Moaz nor Ali ibn Abi Talib and Abu Musa Al-Ash’ari remained long before they converted to Islam.[33]

As for the Bedouin tribes, such as Kinda and Mazhaj, they had a different position. A battle broke out between Hamadan and the Murad Al-Madhahi tribe in that period. Kinda and Madhahij had always been in close contact, and Madhahij was defeated in front of Hamdan and Farwa bin Al-Musayk Al-Muradi announced his separation from the kings of the Kingdom of Kinda because they betrayed him in that battle, according to what was reported, and he went to Muhammad converted to Islam, and the Muhammad appointed him responsible for collecting alms. Khawlan, Nahd tribes and Nakha`, from Madhhaj and Ash'ari people of Abu Musa al-Ash'ari, who were trembling before their arrival: “Tomorrow we will meet our beloved Muhammad and his party.” and Muhammad said to them:[34]

"The people of Yemen have come to you. They are weaker in heart and softer in understanding, faith is Yemeni and wisdom is Yemeni."

But the rest of Mazhaj were still connected to Kindah and did not like the appointment of Al-Muradi as head of the charity, so Amr ibn Maadikarb Al-Zubaidi and several Madhaj people defected and preferred to join al-Aswad Al-Ansi and Farwa ibn Al-Musik managed to manage Al-Muradi from the defeat of Amr bin Maadikarb, and his son Qays was with Fayrouz Al-Dailami the killer of Al-Aswad Al-Ansi,[35] Muhammad Moaz bin Jabal and built Al-Jund Mosque in Taiz on the lands of Al-Sukun and Al-Sakasik, which are still part of the Kinda Kingdom and it is the second oldest mosque in Yemen.[36] After the death of Muhammad, tribal divisions appeared again, and the narrators reported that Al-Ash’ath ibn Qays, the leader of Banu Al-Harith ibn Jabla from Kindah, refused to pay zakat,[37] and it was Sharhabeel ibn Al-Samat Al-Kindi was hostile to Al-Ash'ath and his killer. Indeed, Kinda was divided among itself during that period. The hostility between its ranks continued until the days of the Umayyads.[38] This Sharhabeel assumed the emirate of Homs for Muawiyah, and he was its conqueror and who divided The houses on the tribes in it,[39] He was hostile to Ali ibn Abi Talib and had a great influence in The Battle of Siffin and Al-Ash’ath was in Ali's army.[40] It seems that some of them were Christians, as it was reported that the prince of the Christians of Najran who came to visit Muhammad was a Canadian,[41] Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq sent a force to besiege Al-Ash’ath, who had fortified himself and those with him in a fortress called Al-Najir, while the tribes of Banu Tajib and Al-Sakasik Al-Kindi were in the ranks of the Muslims, led by Al-Husayn bin Al-Numair Al-Sakuni, to spite Al-Ash’ath. Who surrendered after four months of siege, but he converted to Islam again and went out to the Levant and Iraq as an invader, and headed to Al-Qadisiyah at the head of three thousand fighters, following Saad bin Abi Waqqas, and he was one of the eight alongside Amr bin Maadikar who were sent by Saad bin Abi Waqqas to Yazdgerd III.[42] Many of Muawiyah's noble sons descended on Kufa in the year 17 Hijra, and Al-Ash’ath bin Qays subjugated the second rebellion of Azerbaijan and became ruler over it in the caliphate of Uthman ibn Affan And it was said Ali ibn Abi Talib.[43] He died in Kufa during the caliphate of Hasan bin Ali.[44] Al-Ash'ath ibn Qais married Farwa bint Abi Quhafa after Abu Bakr Al-Siddiq released him, which saddened Uyaynah ibn Muhsin that his situation was similar to that of Al-Ash'ath. However, they did not marry him, so he responded to him. A poet from his tribe, Salem bin Dara Al-Ghatfani, said:

Uyaynah bin Hisn Al Adi, you are one of your people, to the core and core I am not like the shaggy, crowned boy who has mastered and is weaned His grandfather the bitter eater and Qais/his speeches about the kings were great speeches If you two have come to an engagement/excuse other than you, it will be eternal He has the prestige of kings and of Al-Ash'ath if an old incident comes Al-Ash`ath ibn Qays ibn Maadi has anguish and pride, and you are an animal.

As for Hadhramaut, it converted to Islam after the conversion of the great leader there Wael bin Hajar when the Messenger sent him a letter. Wael came to Medina and Muhammad ordered the call to prayer in honor of his arrival. It is not known exactly how long he remained in Medina except that he It was reported that Muhammad ordered Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan to accompany him while he was leaving, and he and his people remained in Islam and died in Kufa in the days of Muawiyah and he was on the banner of Hadhramaut in the Battle of Siffin with the army of Ali ibn Abi Talib,[45] and they participated in the conquests of Egypt, and it was reported that Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan He recommended that they be appointed judges and codifiers in that country over other tribes alongside Azd.[46]

The Rashidun Caliphate[edit]

The situation of Yemen was stable during the days of what was known as the Rightly Rightly Guided Caliphate. The Rashidun Caliphate divided the country of Yemen into four provinces, which are the other than Sana’a (including Najran[47]), Mikhlaf al-Jand (central Yemen), Mikhlaf Tihama, and Mikhlaf Hadhramaut, and their reign was stable in Yemen, and not much is known from this period until the late ninth century AD, but Historical sources are full of Yemenis themselves. They participated in Islamic conquests and Abu Bakr al-Siddiq sent Anas bin Malik to Yemen inviting them to fight in the Levant,[48] Anas ibn Malik sent a letter to Abu Bakr informing him of the response of the people of Yemen, and Dhu al-Kala` al-Himyari came with a few thousand of his people,[49] Al-Ala bin Al-Hadrami conquered Bahrain and fought those who apostatized from Islam among them, and Abu Bakr and Omar appointed him over Bahrain as the Prophet had appointed him before them.[50]

Al-Samat bin Al-Asut Al-Kindi, Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tujaybi, Dhu al-Kala` al-Himyari and Hawshab Dhu Dhalim al-Himyari were each of them over Kardus in the Battle of Yarmouk. Sharhabeel bin Al-Samat Al-Kindi – and it was said his father, Homs, and with him Al-Miqdad bin Al-Aswad and he ruled it for twenty years and was one of the people who divided the houses in it[51] Then Malik bin Hubayra al-Kindi took charge of it, and he was the commander of Muawiyah's armies against the Romans[52] The Kingdom of Kinda| was the most important pillar of the Jund of Homs and Jund of Palestine,[53][54] bin Khadij al-Tujaybi was revealed. Jalawla and confronted Madad Al-Rum.[55]

When Saad bin Abi Waqqas left Medina heading to Iraq at the head of four thousand fighters, three thousand of whom were from Yemen,[56] The number of fighters of Mazhaj in The Battle of Al-Qadisiyah was two thousand and three hundred fighters out of ten thousand,[57][58] Their leader is Malik bin Al-Harith Al-Ashtar Al-Nakha’i and Al-Nakha’ is from Abyan and they are still there, and Hadhramaut participated with seven hundred fighters,[59] and Amr] was Ibn Maadikar Al-Zubaidi on the starboard side of Saad Ibn Abi Waqqas in that battle,[57][58] and Omar Ibn Al-Khattab swore Mazhaj Between Iraq and the Levant they wanted to move towards the Levant and they hated going to Iraq like the rest of the people of Yemen. There were four chiefs over Mazhaj Amr bin Maadikarb al-Zubaidi and Abu Sabra bin Dhu’ayb al-Jaafi and Yazid. Ibn Al-Harith Al-Sada'i and Malik Al-Ashtar Al-Nakha'i,[60] Al-Ash'ath Ibn Qays was among those who went out at the head of one thousand and seven hundred fighters and participated with Sharhabeel Ibn Al-Samat in that battle as well,[61] Duraid bin Ka’b al-Nakha’i was the bearer of the banner of al-Nakha’ "The Night of the Harrier" and Kinda Kingdom was defeated that night against the Persians. Likewise,[62] Qais bin Makshuh al-Muradi was in command of the force that attacked Rustam,[63] Mazhaj was one of the most prominent neighborhoods that participated in that battle, to the point that a boy among them was driving sixty or eighty prisoners of the Persian Empire,[64] even their women. They participated in that battle, and they were seven hundred Madhhiji women.[65] And people from Bani Nahd participated in the conquest of Tabaristan.[66]

In the twentieth year of the Hijra, Abdullah bin Qais al-Taraghmi al-Kindi invaded the Romans at "the sea" at the urging of Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan although Omar was hesitant about that,[67] Muawiyah ibn Khadij al-Tujaybi al-Kindi was part of a delegation to Omar ibn al-Khattab in the conquest of Alexandria and the Yemenis were the majority of the army of Amr ibn al-Aas and they were Who planned Fustat and distributed housing on a tribal basis[68] The planning of Fustat was supervised by four people, namely Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tujaybi and Shareek bin Sami al-Ghataifi from Murad Mazhaj and Amr bin Qazam Al-Khawlani and Haywal bin Nashirah Al-Maafiri, and most of the tribes residing in Fustat were Yemeni,[69] And Al-Maafir, Khawlan, Ak, Ash'ari and Tajib participated and Hamdan in the conquests of Egypt, North Africa and Andalusia, and Hamdan and the Kingdom in Giza.[70]

Abdullah bin Aamer al-Hadrami assumed the governorship of Mecca during the days of Othman bin Affan,[71] and Al-Ash'ath bin Qays the governorship of Azerbaijan Yemen was divided between Ali ibn Abi Talib and Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan, so the majority of Hamdan was on the side of Ali ibn Abi Talib their leader Saeed bin Qais Al-Hamdani who was the owner of the Hamadan banner. In The Battle of the Camel and The Battle of Siffin,[72] Yazid bin Qais Al-Arhabi Al-Hamdani was one of the messengers of Ali ibn Abi Talib To Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan calling on him to obey Ali,[73] A large portion of Hamdan is still Shiite to this day, from Zaidi and Ismaili. As for the rest of the tribes, they divided among themselves between the two groups.[74][75] So Malik al-Ashtar al-Nakha’i was at the head of three thousand horsemen. In the army of Ali ibn Abi Talib in the Battle of Siffin and with him Shurayh bin Hani al-Harithi, Ziyad bin al-Nadr al-Harithi and Ammar bin Yasser al-Ansi and they were all from Mazhaj.[76] The heart of Ali's army in the Battle of Siffin was from the people of Yemen,[77] And many of Hamdan loyal to Ali were killed in that battle. Whenever one of them was killed, their banner carrier was carried until another carried it.[78] Malik al-Ashtar used to mobilize his people Mazhaj and say:[78]

"You are the sons of wars, the raiders, the youth of the morning, the dead of the peers, and Madhhaj al-Ta'an"

While Sharhabeel bin Al-Samat Al-Kindi and Malik bin Hubayra Al-Kindi were in the army of the Levant, Hajr bin Adi Al-Kindi and Al-Ash’ath bin Qays were in the army of the Levant. And Abd al-Rahman bin Mahrez al-Kindi and others with Ali,[79] Dhu al-Kila’ al-Himyari was on the side of Muawiyah, and with him were four thousand of his people, and he attacked those loyal to Ali and wounded some of them. They were of great character,[80] Muawiyah bin Khadij al-Tajibi al-Kindi was the one who pursued Muhammad bin Abi Bakr al-Siddiq in Egypt And he killed him by inserting him into the belly of a donkey and burning him,[81] Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan directed Abdullah bin Amer al-Hadrami to Iraq to mobilize them to fight for his side,[82] One of Mazhaj was the one who killed Ali ibn Abi Talib and he was Al-Khariji Abdul-Rahman bin Muljam al-Muradi.[83]

After the killing of Ali, Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan ordered the killing of Hajar bin Adi al-Kindi, but the intercession of Malik bin Hubayra al-Kindi (one of the commanders of the Levant army in the Battle of Siffin) on the pretext that Hujr was the head of those who opposed and criticized Muawiyah,[84] But he accepted his intercession. In Abdullah bin Al-Arqam Al-Kindi,[85] The killing of Hajr bin Adi stirred many people, including the Yemeni tribes, even Muawiyah bin Khadij Al-Tujaybi,[86] So Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan sent one hundred thousand dirhams to Malik bin Hubayra Al-Kindi with the aim of silencing him.[87] Things returned to normal and the conquests resumed. Rabi’ bin Ziyad Al-Harithi Al-Madhaji Khorasan and conquered Yazid bin Shajara Al-Rahawi Al-Madhaji and Abdullah bin Qais Al-Taragmi Al-Kindi the sea and invaded Sicily and was the first Arab to invade it,[88][89] bin Hudayj al-Tujibi Africa (Tunisia) invaded three times, he invaded Nubia, where his eye was damaged and he became one-eyed.[90] He assumed the emirate of Egypt and Crenasia.[91]

Muawiyah died, and Hamdan remained loyal to the sons of Ali ibn Abi Talib and Abu Thumama al-Sayidi al-Hashidi was their head and part of Kinda Kingdom and Mazhaj Muhammad bin Al-Ash'ath Muslim bin Aqeel was killed while Amr bin Aziz Al-Kindi and his son Ubayd Allah were on a quarter of Kinda Kingdom and Rabi'ah took the pledge of allegiance For Al-Hussein bin Ali,[92] But Muhammad bin Al-Ash’ath Al-Kindi feared that Hani’ bin Urwa Al-Muradi Al-Madhaji would be killed because of his position in Iraq and he was from Allies of Muslim bin Aqeel,[93] He was killed by the servant of Ubaid Allah bin Ziyad called "Rashid." So Abdul Rahman bin Al-Husayn Al-Muradi proceeded to kill the master and killed Ibrahim bin Al-Ashtar Al-Nakha’i Al-Mazhaji Ubayd Allah ibn Ziyad.[94][95]

Umayyads[edit]

Historical sources are very scarce about the situation of Yemen during that period, and like previous crises, the Yemenis were divided between Hussein bin Ali and Yazid bin Muawiyah with the exception of Hamdan which continued to mourn Hussein until the caliphate. Marwan ibn al-Hakam,[96] Kinda acquired thirteen heads of the family of Hussein ibn Ali and Mazhaj Seven,[97] Sinan bin Anas al-Nakha'i al-Mazhaji was the one who cut the head of Hussein[98] As for Hamdan there were many of them who were killed in The Battle of Karbala, the most prominent of whom were Abu Thumama al-Saidi and Habashi bin Qais al-Nahmi and Hanzalah bin Asaad al-Shabami (relative to Shibam Kawkaban), Saif bin al-Harith bin Saree al-Jabri, Ziyad bin Urayb al-Saidi, Siwar bin Munim Habis al-Hamdani and Abas bin Abu Shabib Al-Shakri and Barir bin Khudair Al-Hamdani,[99] He was from Hadhramaut who participated in that battle alongside the Umayyads Among them are Hani bin Thabit al-Hadrami, Usayd bin Malik al-Hadrami, and Sulaiman bin Awf al-Hadrami,[100] Hakim bin Munqidh al-Kindi went out to Kufa on horseback, mobilizing the people to avenge Hussein in the year 65 For Hijra,[101] He was among those who were killed with Sulaiman bin Sard al-Khuza’i in the Revolution of the Tawabin.[citation needed]

Some sources say that Yemen pledged allegiance to Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr in addition to for Hijaz,[102] and the details regarding that are non-existent, but it was Al-Husayn bin Al-Numair Al-Sakuni Al-Kindi played a major role in gathering the people of Yemen in The Levant alongside Marwan bin Al-Hakam,[103] and before that he was in the army of Muslim bin Uqba who invaded Medina during the Battle of al-Harra in the caliphate of Yazid bin Muawiyah and left the army to Mecca with Yazid's desire and besieged Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr,[104] He pledged allegiance to Marwan ibn al-Hakam, and a number of people from Kinda Kingdom were insisting on al-Husayn ibn al-Numair to present Khalid ibn Yazid ibn Muawiyah because they were his maternal uncles,[105] But they pledged allegiance to Marwan bin al-Hakam on the condition that they hand over Balqa in Jordan and make it theirs, so bin al-Hakam agreed,[106] There were two tribes of Kindah (Al-Sukun and Al-Sakasak) with Marwan bin Al-Hakam in the Battle of Marj Rahit which confirmed the rule of Marwan bin Al-Hakam and it was the beginning of the second phase of The Umayyad state and one of the most important battles that contributed to the development of tribal divisions among the Arabs.[107]

Many of Hamdan and Nakha from Mazhaj and Bani Nahd joined Al-Mukhtar al-Thaqafi in his revolution to investigate the killers of Hussein, and he was Asim bin Qais bin Habib. Al-Hamdani was on a quarter of Hamdan and Bani Tamim,[108] and he was on Bani Nahd Malik bin Amr al-Nahdi and Abdullah bin Sharik al-Nahdi,[109] And Sharhabil bin Wars al-Hamdani went at the head of three thousand fighters, most of whom were mawali and were not Arabs. Except for seven hundred, they headed towards Medina and then to Mecca to besiege Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr, but he was killed by a plot hatched by bin Al-Zubayr and the rest of his army returned to Basra,[110] Al-Husayn bin Numair Al-Sakuni was killed during the revolution of Al-Mukhtar Al-Thaqafi, and Al-Mukhtar was killed during Mus’ab bin Al-Zubayr's departure to him. To the right of Al-Mukhtar Al-Thaqafi was Salim bin Yazid Al-Kindi, and to his left was Saeed bin Munqidh Al-Hamdani, and Muhammad bin Al-Ash’ath Al-Kindi was in the ranks of Musab bin Al-Zubair.[111]

When Abd al-Malik bin Marwan entered Kufa, he saw Bani Nahd in which there were few people, and he was surprised by their presence despite their small number. They said, "We are stronger and more powerful." When he asked them by whom?, they answered him: “By whom.” With you from us, O Commander of the Faithful.” Kinda joined Abd al-Malik as well, and over them was Ishaq bin Muhammad al-Kindi,[112] and Abd al-Rahman bin Muhammad al-Kindi] left. Known as "Ibn al-Ash’ath," the leader of the famous revolution later at the head of five thousand fighters to fight Kharijites,[113] Uday bin Uday al-Kindi and Amira bin al-Harith al-Hamdani were sent to fight Saleh. Ibn Masrah al-Tamimi al-Khariji was killed.[114]

In the year eighty AH, Abdul-Rahman bin Muhammad bin Al-Ash’ath Al-Kindi headed to Sistan, after the annihilation of the army of Ubayd Allah bin Abi Bakra by Turk, and the relationship between Al-Hajjaj bin Yusuf and Abdul-Rahman bin Al-Ash’ath was very bad, to the point that Abdul-Rahman's uncle called on Al-Hajjaj not to send Abdul-Rahman, who used to call Al-Hajjaj " Ibn Abi Raghal." Whenever Al-Hajjaj saw Abd al-Rahman, he said: “How arrogant he is!” Look at his walk, and by God, I was about to behead him.” Abd al-Rahman was arrogant and proud of himself and of his lineage to the kings of the Kingdom of Kindah.[115] He used to sit in the gatherings of his uncles from Hamdan and say: “And I am as Ibn Abi Ragha says, if I do not try to remove him from his authority, So he exerted himself as long as he and I had to stay.” [116] Abd al-Rahman set out at the head of forty thousand fighters. People called him the “peacock army.” [117] Abd al-Rahman invaded the country Turks and their friend offered to pay the tax to the Muslims, but Abd al-Rahman did not answer him until he annexed a large part of their country and stopped due to the onset of the winter season. Al-Hajjaj sent a letter to Abd al-Rahman forbidding him to stop, and threatened to depose him and appoint his brother Ishaq bin Muhammad al-Kindi as commander of the people.[118] Abd al-Rahman consulted with his soldiers and said He does not contradict an opinion he saw yesterday, and Amer bin Wathilah Al-Kinani agreed with him. They called for the removal of what he called "the enemy of God," Al-Hajjaj,[119] That was the beginning of one of the most violent and intense revolts against the Umayyad state Abd al-Malik ibn Marwan sent supplies to al-Hajjaj, and he killed Abd al-Rahman ibn al-Ash'ath Mutahhar ibn al-Harr al-Judhami and Abdullah ibn Rumaitha al-Tai, and stormed Basra, so Basra pledged allegiance to him and all Hamdan who were his maternal uncles, and the reciters and followers joined him. Such as Saeed bin Jubair and Muhammad bin Saad bin Abi Al-Waqqas and the great status of Abd al-Rahman Fakhshi Abd al-Malik bin Marwan and he panicked and proposed to the people of Iraq to remove al-Hajjaj And Abd al-Rahman's leadership over them greatly saddened al-Hajjaj.[120] Ibn al-Ash’ath's campaign continued for nearly four years, and he fought eighty-some battles with al-Hajjaj and his armies, all of which were in favor of Abd al-Rahman, but he was defeated in the [[battle] Deir al-Jamajim|Deir al-Jamajim]] So Abd al-Rahman fled to the country of Turk with Ubaid bin Abi Suba` al-Tamimi, so al-Hajjaj sent Amara bin Tamim al-Lakhmi requesting Abd al-Rahman. When al-Kindi realized that he would be handed over to al-Lakhmi, he chose to commit suicide rather than commit suicide. It is delivered to the pilgrims in the year eighty-five AH.[121]

Talha bin Daoud al-Hadrami assumed the governorship of Mecca during the days of the seventh Umayyad Caliph Suleiman bin Abdul Malik and Bashir bin Hassan al-Nahdi the governorship of Kufa and Basra Sufyan bin Abdullah Al-Kindi,[122] Ubadah bin Nasi Al-Kindi took over the governorship of Jordan during the days of Omar bin Abdul Aziz and he was Raja bin Haywa Al-Kindi the latter's advisor and master of the people of Palestine,[123] during which Al-Samh bin Malik Al-Khawlani took over Andalusia and opened a number of forts and was killed in the Battle of Toulouse in France and was succeeded by Abdul-Rahman Al-Ghafiqi who was killed in the battle of Balat The Martyrs.[124]

Tribal disputes broke out throughout the country, specifically between the Yamaniyya and Qays Aylan. Ta'i, Ghassan, Banu Amila, Lakhm, and Leprosy in addition to the tribes of Rabi'ah. Marwan bin Muhammad was the last Umayyad caliph, known as "Donkey" due to his many wars, so Homs (one of the most important strongholds of the Yemeni tribes) revolted against him during the days of disputes, and he left. Abdullah bin Yahya al-Kindi also ruled in the year 128 AH, but he was not motivated by tribal motives. He was considered one of the major imams of Ibadi and the judge of Ibrahim bin Jabla al-Kindi, governor of the Umayyads in the late days of the Umayyads, and he dominated. Abdullah Ali Hadhramaut and Sanaa opened the money coffers and distributed them to the poor but did not take anything from them,[125] Abdullah's army, led by Al-Mukhtar bin Awf Al-Azdi was able to storm Mecca, but he was defeated at a site called Jerash, and his army returned to Yemen.[126]

Yemeni mini-states[edit]

Some Yemeni tribes supported the Abbasid call at its beginning,[127] The country became independent from the Caliphate in the year 815, and several states were established throughout the country for sectarian and tribal reasons, so the State of Bani Ziyad and its founder Muhammad bin Abdullah bin Ziyad Al-Umawi was established in the year 818, and it was a state nominally subordinate to the center of the caliphate in Baghdad and it extended its influence from Hilli bin Yaqoub south of Mecca passing through Michalaf Jerash (Asir) and even Aden and they made Zubaid in Al-Hudaydah as their capital.[128] While the state of Banu Yaafar and its founder Yafar bin Abd al-Rahman al-Hawali was established, which is the Himyari[129] in 847 in Sanaa and its surrounding countryside and Al-Jawf, and the mountainous region between Saada and Taiz[130] And Saada fell into the hands of Imam Yahya bin Al-Hussein in the year 898,[131] Where Mawla Hussein bin Salama was able to preserve the state of his masters Bani Ziyad and confront Abdullah bin Qahtan Al-Himyari, but Al-Himyari was able to burn Zubaid[132] Ibrahim bin Abdullah bin Ziyad, the last prince of the Ziyad family, was killed by his loyalists Nafis and Najah, who established the state of Bani Najah on the ruins of the state of Bani Ziyad in Tihama, and they enjoyed the support of the Caliphate center in Baghdad.[133]

The Ibadis established several states for themselves in Yemen and large parts of Hamdanand Khawlan pledged allegiance to Imam Yahya bin Al-Hussein and left the Hashid Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi the founder of the Sulayhid state, and he fought many battles with Zaidi Imams and Najjahis in Tihama and various tribal forces in Saada, passing through the central regions to Aden and Hadramaut, and he was able to bring together the countries of Yemen under the rule of one state. He was the first to achieve this after Islam and took over from Sanaa The capital of the country.[134] Ali bin Muhammad al-Sulayhi was able to annex Mecca in the year 1064,[135] However, they did not try to impose their doctrine.[136] In the year 1138 Sultan Suleiman bin Amir al-Zarahi, the last Sulayhid sultan, died, and the regions became independent, including Sanaa, which was controlled by three families from Hamdanand Aden became independent. And over it Banu Zurayi and they are from the Yam tribe from Hamdanas well, and Al-Mukarram Al-Sulayhi was the one who appointed them over it,[137] The Najahs returned for a short period to Tihama but Ali bin Mahdi Al-Himyari eliminated them, imposed a certain lifestyle on them, and isolated them from society in the year 1154 and that was the beginning of the emergence of a group of Modern-day Yemeni citizens are known as Akhdam,[138][139] Grudges between tribal leaders prevented them from unifying their position towards Ayyubids,[140] Until the Ayyubids were defeated in 1226 by the Zaidi tribes (Hashid, Bakeel, Sanhan, Khawlan... etc.)[141] Omar bin Rasool established a state known as the apostolic state that was one of the strongest kingdoms that Yemen witnessed throughout its history after Islam.[142] It is one of the longest-lived Yemeni states in the country's history after Islam. They built Cairo Citadel in Taiz and Mosque And Al-Muzaffar School

In fact, this division between the Arab Arabs and the Arabized Arabs is due to what was mentioned in the Old Testament, and it was derived from what is meant by the news of the beginning of creation. Then the genealogists and informants agreed to divide the Arabs in terms of lineage into two parts: Qahtaniyah, their first homes in Yemen, and Adnaniyah, their first homes in Hijaz.[19][20]

Mazhaj established a strong state, which is the state of Banu Tahir and their city Radaa, but they did not submit to the Zaidi Imamate, and the Tahirid army was defeated before Imam Al-Mutahhar ibn Muhammad in 1458,[143] The Tahirids were able to repel the Portuguese from Aden, and Hadramaut fell to the Kathiriyya Sultanate in the late fifteenth century, and the Zaidi Imam Al-Mutawakkil] was able to Sharaf al-Din with the commander of the Mamluk army, they were able to defeat the Tahirids from Taiz, Radaa, Lahj and Abyan,[144] The fall of the Tahirid state was complete, and they remained in control of Aden until the year 1539, so the Ottomans took control of Aden, then Taiz, Al-Hudaydah, and the rest of Tihama,[145] The Ottomans succeeded in subjugating Aden and it was one of the worst eras that passed through that city. The Zaidi tribes, led by Imam Al-Mansur Al-Qasim were able to defeat the Ottomans and the reason for their success after several Revolts suppressed by the Ottomans because they learned to use firearms,[146] They liberated Aden from the Turks in 1644, and Yemen was the first region to separate from the Ottoman Caliphate,[147] The tribes (Hashid, Bakeel, Sanhan, and Khawlan) were able to extend their control over the entire Country of Yemen in the year 1654 In favor of the Zaidi Imamate.[148]

An overview of the tribes[edit]

The Kingdom of Sheba included many tribes, mentioned in the texts of Musnad script, and nothing is known about them, such as the tribes of "Fishan," “Dhi Ma’ahir," “Dhi Khalil," “Dhi Lahad," and many others. They were not mentioned in the writings of the genealogists and the people of the news, but among the tribes that were mentioned in the books of the people of the news and still exist today are the tribes of Hamdan, Kinda and Mazhaj; the last two were Bedouins.

Hamdan[edit]

Hamdan is the name of an ancient Sabaean land, mentioned in the seventh century BC,[149] According to the informants, Hamdan is the ancestor of the tribes Hashid and Bakeel, and according to them he is Hamdan bin Malik bin Zaid bin Usala bin Rabi’ah bin Al-Khayar bin Malik bin Zaid bin Kahlan bin Saba,[150] The greatest of their gods was the god Talab Riyam, and they believed that he was their father and the son of the greatest Sabaean god El-Maqh.[151] Hamadan was mentioned in the ancient Musnad texts in the form "Ardam Hamdan," which literally means "the land of Hamad,"[152] And the barren land is the dry land that does not grow.[153]

Hamdan is divided into two main parts: Hashid and Bakil, which are large tribes. The oldest mention of Hashid or "Hashdum" as read in the ancient Sabaean texts of the century 4th century BC,[154] As for Bakil, it dates back to the 6th century BC,[155] Since the fourth century BC, and for mysterious reasons that may be revealed by modern archaeological discoveries, The kings of the Kingdom of Sheba belonged to one of the branches of Hamadan,[156] but the leader of the Hashid “Yarim Ayman”, He managed to monopolize the kingdom around the second half of the second century BC,[157] Then the kingship moved to Bakil in the second half of the first century BC, and Bakil's control ended after the victory The Himyarites led by Dhamar Ali Yahbar I in the year 100 AD.[158]

Hamdan resides in Sanaa and its environs, and they have an extension in Amran Governorate, with the presence of separate sheikhdom tribes outside the borders of The Republic of Yemen such as Yam Tribe, according to Western sources mention the Hashid and Bakil as alliances of several tribes or a “tribal union" of several clans, which is an ancient custom that has existed in the Arabian Peninsula since ancient times, as large tribes include smaller tribes for various circumstances. The word "Bakeel" is derived from "Yabakal", which is the mixing or bringing together of things according to a theory. It was also said that Bakeel means a beautiful man,[159] but as long as the word is mentioned in Sabaean texts, it may have another meaning. The word Bakeel is undoubtedly a Sabaean word. The name Hashid and Bakeel are as old as the Kingdom of Sheba itself.[160] In the past, the Hashid and Bakil tribes were called “the wings of the Zaidi Imams,”[161][162] But this does not necessarily mean that all Hamadan are Zaidi, or that Zaidi are confined to them, but rather they are that way from a historical perspective.

Although the 26 September Revolution started from Taiz, an area whose population is less connected to the tribe than other Yemeni regions despite its presence,[163] However, Hamedan played an important role in supporting the revolution, which gave it influence and power centers that enabled them to make political decisions for the emerging Yemen Arab Republic in the Arabian Peninsula, and this provided an opportunity for the tribe to practice economic and commercial activities on a broader scale, which made it influence the climate Traditional cultural and social and its continuity. Some sources reported that many families from Hashid and Bakil changed their allegiance from time to time according to what was required by political interest.[164] He rallied the most politically influential tribes in the Republic of Yemen since The fall of the monarchy in 1962 and after Yemeni unity.[165]

Bakil is divided into four main sections, which are Arhab, Marhaba, Nihm, and Shaker. They are the most numerous of the Yemeni tribes, and many tribes were included among them, so they became the largest tribal union in Yemen.[165] But they are not under the influence of the Hashid, and this is due to their multiple sheikhdoms and their lack of stability in one family.[165]

Kinda[edit]

Kinda (Musnad:

![]() ), an ancient Arab tribe mentioned in the texts of the second century BC,[166] This tribe was known in heritage books as "Kinda" Kings",[167] The Kingdom of Kindah established in Najd[168] The history of the Kingdom "Pre-Islamic" is marred by a lot of ambiguity, as news writers talked about it and many writings were discovered in Qaryat Al-Faw, written in The old Musnad script is what researchers rely on to know their history away from the fanaticism and partisanship of the lineage and the people of the news.

), an ancient Arab tribe mentioned in the texts of the second century BC,[166] This tribe was known in heritage books as "Kinda" Kings",[167] The Kingdom of Kindah established in Najd[168] The history of the Kingdom "Pre-Islamic" is marred by a lot of ambiguity, as news writers talked about it and many writings were discovered in Qaryat Al-Faw, written in The old Musnad script is what researchers rely on to know their history away from the fanaticism and partisanship of the lineage and the people of the news.

Kindah is historically divided into three sections, namely "the sons of Muawiyah," and to this is added the word "the noble ones," since they were the kings of Kindah,[169][170] And the two sections. The others are "Sukun" and "Sakasik," and more than fifty tribes branch out from these three divisions. They are located in Yemen, Sultanate of Oman, and United Arab Emirates, and there are clans in Iraq and Jordan that still cling to their ancient lineage.

The oldest Sabaean texts that refer to "Kinda" referred to them in Najd, in the second century BC,[171] The texts of Musnad script referred to Kinda and Madhhij as "the parsing of Sheba."[172]

Mazhaj[edit]

The oldest mention of the Mazhij tribe dates back to the second century BC.[173] They were part of the Kingdom of Kindah, and they were mentioned in the Al-Namara Inscription of the king of The Kingdom of Al-Hirah, and the texts of the Musnad script described them as " The Bedouins of Sheba".[174] Madhhij is one of the sections to which many tribes in Yemen and the rest of the Arabian Peninsula trace their origins, and a number of other countries who maintained their tribal connections. The tribe was known in Arab heritage books by the title "‘Mazhaj al-Ta’an’.”

Mazhaj is historically divided into three sections: Saad clan, Ans, and Murad. They are found in most areas of Yemen and they are many tribes. Such as Nak', and they are found in Al-Bayda Governorate, Abyan, and Banu Al-Harith bin Ka'b, and in Shabwa, Ma’rib and Sada’, and Ubaida in Ma’rib and Al-Habbab From Qahtan as well, and Al-Minhali in the north of Hadramaut and Sanhan, and around Sana’a, which is the tribe of Ali Abdullah Saleh and Hakam in Tihama, and the tribe Al-Had'a who are from Murad, and Al-Qaraada'ah in Ma'rib who are also from Murad, and among them is Sheikh Ali bin Nasser Al-Qardai Al-Muradi, the killer of Imam Yahya Hamid Al-Din.

The Anas tribe is found in Dhamar, and the Anas tribe, and one of them is Al-Ansi, which is a tribe originally from Mazhaj, but it entered Bakil, like many other tribes, and there is a tribe Al-Riyashi, and one of them is Al-Riyashi in Al-Bayda Governorate and Al-Dhale’ from Mazhaj, and some news people mentioned that they are from Kinda And many others. There are many tribes in Madhaj, including the Al-Dulaim clans in the desert of Iraq and Syria, which trace their origins back to Zubaid.

Himyar[edit]

He is the eldest son of Saba, and the brother of Kahlan, according to the reports,[175][176] Although the Himyarites were the ones who overthrew Saba and Hadhramaut and united them into one state, there is no indication that Himyar were sons of Saba, as the ancient Sabaean texts mentioned them as "the son of a paternal uncle," and this uncle was the greatest god of the kingdom. Ancient Qataban, not Sheba,[177][178] They seized "Dahsum", which is the land of the Yafa and Al-Ma’afer tribe, and fought with Saba for a long time, until they completely overthrew it around 275 AD.

There are many tribes that are attributed to Himyar in all parts of Yemen and outside it, and talk about their divisions depends on the writings of the informants, not the Musnad inscriptions. The Musnad texts did not mention that Himyar, or "Himyar," was a man and had children, or that his real name was "Al-Arnaj," but because he wore a robe. Hamra is called Himyar,[179] Like Sheba, the Himyarites are an ancient ruling family. The tribes joined them against Sheba and the informants considered them "Hymyar tribes."[180]

The oldest text discovered about Himyar is a Hadhrami text that refers to the construction of a wall around Wadi Labna Hadhramaut. Its mission was to prevent the Himyarites from attacking the caravans of Kingdom of Hadramaut, between Shabwa and the port of Qena, and to block them from encroaching on the territory of the Kingdom of Hadhramaut towards the coast. The text dates back to the year 400 BC (fifth century),[181] The Himyarites established their government at the end of the second century BC, at a time when the Kingdom of Sheba was greatly weakened, so the Himyarites swept the central and southern regions of Yemen "currently", and took over Dhofar Yarim as their capital,[182] The first it was said of the Himyarites was Shammar Dhu Raydan, who fought many battles against Ili Sharh Yahudhab, and allied with Every enemy of the Sabaeans, but he did not win and was eventually forced to reconcile with the King of Sheba, but rather joined as a commander in his armies,[183] > Himyar was divided, some of whom were allied with Sheba, and some of them remained independent and did not recognize the government of the Sabaean, which was weak at that period, so four royal dynasties appeared in Yemen, Hashid, and Bakil and two dynasties from Himyar, each of whom it was said called himself "King of Sheba and Dhu Raydan",[184] The turmoil continued for a century and a half, and according to some estimates, twelve Himyarites appeared, before the Himyarites were able to establish their king in the year 275 AD, led by Shammar Yaharash.[185]

Hadhramaut[edit]

Hadhramaut is the name of an ancient tribal union. Genealogists and informants considered it a belly of donkeys, and some of them said that a man named "Amer bin Qahtan" used to kill a lot. Whenever his enemies saw him, they said, "Hadhramaut",[186] And other narrations that have no archaeological support or evidence, so Hadhramaut is not Himyarite, rather it is older than Himyar,[187] The Hadhrami tribes are among the Himyarite tribes, such as Siban, Noah, Al-Sadaf, and Al-Sa'ir. Although no writing was discovered in the Musnad, relating to a genealogy of all the tribes, including the Hadhramaut tribes, proving the "Himyarite" of these tribes. Siban and Noah are ancient tribes, and Siban was mentioned alongside Al-Mahra, in a text written by Samifa Ashua Al-Himyari, and no chain of transmission was mentioned in the text. This described them as being alive from Hadhramaut, which is closer to the truth.[188][189] Whereas these tribes, such as Siban, Nuh, and al-Humum, are the closest to the Mahra and the inhabitants of Socotra in their features and clothing, and have no relation to Himyar.

In general, Hadhramaut is considered somewhat less tribal than other regions in Yemen, despite the presence of tribes, and in a study conducted by the American researcher Sarah Phillips in cooperation with Sana’a university, the percentage of those who declared that loyalty should be to the state and not to the tribe was 70% higher than the population of Amran Governorate Al-Ahmar Centre.[190]

Quda'ah[edit]

The name Qada’ah nor "Adnan" was not mentioned in ancient texts that predate Islam, and only a little about "Qahtan" (Qahtan) was mentioned in the Musnad texts as a land name, not in the form that the informants portrayed in the Umayyad and Abbas eras.[191] Qada'ah includes many tribes, some of which are located in the south of the Arabia, and some of which are in the north of it, and it was the era of the Bani Umayyads. The beginning of boasting among the Arab tribes, and each attributed the tribes he wanted to his section, and composed legends and composed satirical poems against the other sections, until the matter reached the next, and each client was proud of the origin of his master and satirized the others,[192] The Battle of Marj Rahit] was one of the most important wars that contributed to fueling grudges. The Yemenis were on the side of Marwan bin Al-Hakam, and the Qaysiyyah were on the side of Abdullah bin Al-Zubayr,[193][194] The disagreement among informants and genealogists about "Quda’ah" is due to this boasting. The tribes that are considered "Quada’ah" are mentioned in the texts of the Musnad without ancestors, but rather as peoples. The most prominent of these tribes is Khawlan, which was mentioned as "Khulan," and " Dhi Khawlun", and other "Qada’i" tribes such as "Kalb" (Banu Kalb), "Nahd" and "Adhrat" (Adhrah), but it was not mentioned as a single tribal bloc called "Otter" at all.[195]

Yafa'a[edit]

Yafi' is a tribe belonging to Himyar bin Saba',[196][197][198] and their country was known in the texts of Al-Musnad in the name "Dahs" or "Dahsam" and then it was named after them later during the era of the Upper Yafa Sultanate,[199][200][201][202] The Yafa tribe in the Yafa region is divided into two main sections: Banu Qasid and Banu Malik,[203][204] and they established several sultanates throughout history in Yemen and abroad, such as The Tahirid State[205] The Emirate of Al-Kasad[206] and The Qu'aiti Sultanate[207] and The Emirate of Al Buraik[208] and others.[209]

As for outside the Yafa’ area, they are usually divided into three major clans, namely Al-Mousta, Al-Dhabi, and Banu Qasid, and they are all called Ayal Malik or Banu Malik, in reference to Yafa’ Na’ta's grandfather, who was nicknamed Malik. They are spread in almost all governorates of Yemen, especially in Hadramaut.[210][211][212] They were also famous for being among the first tribes to pay attention to the Najdi Salafi call in Yemen during the era of Imam Muhammad bin Abdul Wahhab.[213][214]

Yafa' played a role alongside other tribes in the October 14 Revolution against the British colonizer, but unlike the northern regions of the country, the revolution and the evacuation of the colonizer did not increase the influence of the tribes, but rather increased their weakness and disintegration with minor differences. From one southern governorate to another, this is due to the policies of the Yemeni Socialist Party, which seized power after the expulsion of the English colonialists from Aden. The Socialist Party has placed this among its priorities,[215] However, tribal (or more precisely regional) affiliations emerged to the fore again during the 1986 War, among supporters Abdul Fattah Ismail and Ali Nasser Muhammad.[216]

al-Aulaqi[edit]

The Aulaqi is one of the largest and most influential tribal blocs in the south of the country,[217] They are a tribal confederation from Shabwah Governorate in the eastern desert of Yemen. Most of the families of the confederation trace their origins to the Himyar and Kinda and Mazhaj and appeared under this name in the late eighteenth century. They established several sultans in The Modern History of Yemen such as the Upper Aulaqi Sultanate and the Lower Aulaqi Sultanate and others such as the Al-Daghar Sultanate and their sheikhdom in the Al Farid, It is a cohesive tribe compared to other tribes residing in the south of the country, and they are located in Shabwa.

Traditional tribal structure[edit]

The tribal structure can be classified into a number of organizational levels, namely: the tribal union, the tribe, the clan, and the house. This is an academic classification, but at the level of daily use, the term tribe is used to refer to the tribal union. It is also used to describe the tribe and the clan, and by comparing the tribal division with the administrative division of Yemen, the "tribal union" extends at the level of a number of governorates, while the "tribe" often coincides with the directorate, although it sometimes includes several directorates. Sometimes, more than one tribe shares the same district. As for the "clan," it corresponds to the center or isolation, while the house corresponds to the village, and many Yemeni villages bear the designation of a house (such as [[house] Al-Ahmar (Sanhan)|Beit Al-Ahmar]]), indicating a spatial or administrative bond and a kinship bond at the same time.[218]

Although studies of genealogy see that the lineage bond is the basic bond in society at its various levels, this generalization is incorrect, as many political and economic factors have played a role in Formation and restructuring of tribal unions, through fraternal system.[219] Some tribes broke away from the Mazhaj tribal union, joining the Hashid tribes union and the Bakil union,[220] Therefore, the bond at the level of "tribal union" is a bond based on loyalty, while at the tribe level, the bond is based on common interest, the tribe at this level is an organization for managing natural resources, and kinship forms the bond at the level of clan or house, as it includes individuals related by kinship to the fifth or The sixth or seventh.[221]

Social structure[edit]

Historically, the Yemeni tribe formed an integrated political and economic unit independent of other units. It represented an organization for managing the collectively owned natural resources, a military unit responsible for defending its members and the individuals and groups affiliated with it, and a social organization that regulates the relationship between its members. The social status of individuals in the tribal group, the social relationships regulating their daily dealings, and the patterns of their social behavior were determined on the basis of the roles they played in the field of producing and protecting the economic requirements of the tribal group, so the tribal economy was in the Arabian Peninsula according to "Khaldun al-Naqib" is the economy of conquest, so the individuals who carry out the tasks of protecting the tribe occupied a high position in the tribe. The tribe was not composed only of individuals who descended from One common origin, but individuals from outside the kinship unit joined it, either optionally through the system of fraternization between the Companions, or compulsory through the annexation and annexation of prisoners of war, and the individuals who join the tribe occupy Through fraternization, an equal status is given to its original members, as long as they are committed to paying the "fine" and contributing to its defense.[222]

The Yemeni people inherited very ancient social traditions and customs dating back to pre-Christian times, related to social patterns and their roles,[223] The ancient Yemenis looked To the Makariba or Soothsayers a look of veneration and respect, as they represent the religious authority of the community, in addition to the fact that the unit of dealing in "tribal society" is the family, not the individual, the Sayyidah occupied The Hashemites had a high social status in the tribes with which they were associated, and their primary function was mediation between the tribes, in addition to a tribal custom that required the tribe to protect the neighbor, as the "lord" does not fight or carry weapons. They lived under the protection of the tribes.[224]

They are followed by the class of "sheikhs or judges," who are of tribal origin, but they do not often carry weapons.[225] Then "the tribe" is the one who usually carries weapons, and may work with Agricultural work However, they are averse to manual and craft work, and the truth is that "the tribe" is the highest social class, and the position of the "gentlemen" and judges is only with the consent and conviction of the tribes.[226] There were classes that occupied a low social status, including the craftsmen and craftsmen class, and there were the "Muzayna" who were the circumcisers, barbers and cuppers, and there were the "Qashamen" who were the vegetable sellers and owners of stalls and carts, and there were the "Dawasheen" who recited welcome poems and sang Al-Zamil, and protection was provided to these groups of tribes due to the need for their services.[227]

Distribution of power[edit]

The distribution of power in the traditional tribal society in Yemen took a hierarchical pattern parallel to the hierarchy of the tribal organization. In the Hashid tribes, the "Sheikh of the Sheikhs" stands at the head of the tribal authority, followed by the "Sheikh of Al-Daman," then the sheikhs. Then the headmaster and the secretaries. In the Bakil tribal confederation, there is the "Sheikh of Sheikhs," followed by the tribal heads, the "Captains.",[note 1] then the sheikhs, followed by the elders and the trustees. As for the tribes of Hadhramaut, each outfit is headed by a "tailah," and each tribe is headed by a "colonel.",[note 2] each thigh is headed by an "intruder", and the term sheikh in Hadhramaut was limited to sheikhs of religious knowledge.

Those holding the rank of "Sheikh of Sheikhs and Sheikhs of Al-Daman" in the Hashid tribes and their counterparts in other tribes constitute the elite and the political authority of the tribe,[228] Or what they are called in Islamic historical writings “People of Solution and Contract",[229] They are authorized by their tribes to conclude treaties, agreements, and alliances with the state and other tribes or dissolve them, and to represent the tribe before the state and other tribes.

As for those with the third rank in the distribution of power, "the sheikhs" and the equivalent, they constitute the [[military] elite] in the tribe, and they undertake the tasks of mobilizing tribal fighters, and leading them during wars. Next in rank are the "aqal and secretaries" and their counterparts. They constitute executive authority in the tribe, as they collect zakat and carry out what those of higher rank assign to them, such as summoning liabilities and documentation covenants and supervising the distribution of water irrigation, and other tasks.[230]

Despite the differences in tribal authority structures from one tribal union to another, what is common to all of them is that the holders of positions of tribal authority were chosen by members of the tribe directly or indirectly. The sheikhs in the country of Al-Fadhli Chosen by members of their tribes,[231] The same was true in the Al-Wahidi Sultanate, and in the Al-Fadhli tribes in Abyan, and in some tribes such as the "Ibn Abd al-Mani" tribe, the sheikhs were circulated. Among its three divisions, and in the Hashid and Bakil tribes, tribal sheikhs were chosen in the past through the signature of the village sheikhs and headmen, but currently the sheikhdom is confined to specific houses, and has become hereditary, as the eldest son becomes a sheikh after the death of his father.[232][233] And in Hadhramaut The presenters were chosen through consultation and consensus among the "intruders" of the tribes, and he was installed in a meeting called the "Intruders’ Meeting." In general, the sheikh in traditional tribal society was subject to accountability from the tribe, and could be replaced if he was found to be arrogant or tyrannical.[234]

As for the holders of the first rank, "Sheikh of Sheikhs," the method of their selection was and still is done through a mechanism similar to the system of Allegiance,[235] Sheikh Sadiq al-Ahmar was pledged allegiance, succeeding his father Abdullah al-Ahmar in 2008, and in the same manner, Sheikh Sinan Abu Lahoum was installed as sheikh of the sheikhs of Bakil in 1977, as well as the inauguration of his son after him at a tribal conference in 1982.

The politicization of the social authority of the sheikhs of the tribes had negative effects on the state and the tribe alike, as it led, at the tribal level, to its transformation From an egalitarian structure to a hierarchy structure, the transformation of social authority from an authority based on acceptance to a compulsory authority, and the weakening of social relations between the members of each tribe, and the tribal sheikhs are no longer representatives of their tribes before the state, but rather they have become representatives of the state in their regions and among their tribes, and therefore they are no longer accountable to the members of the tribe, which has contributed to the erosion of the intermediary space between the state and society.[236] At the state level, the politicization of the social authority of tribal sheikhs contributed to giving the state the features of a sultanate, weakened its ability to enforce the law, contributed to the tribe and the government sharing state power, and weakened the government's ability to monopolize the exercise of political power.[237]

Social relations[edit]

Social relations in Yemeni tribal society were characterized by a collective nature. The unit of dealing was the family, not the individual. Ownership of pastures and natural resources was collective property. Individual disputes often turned into collective disputes[238] The Yemeni tribes designed a customary justice system for arbitration, based on settlement and reconciliation, not on punishment,[239] In the tribe there is no authority authorized to impose punishment on violating persons,[240] Tribal sheikhs are arbitrators between tribes, not judges over them. Therefore, the phenomenon of revenge spread among the Yemeni tribes, and revenge was not taken from the killer, but from any member of the clan to which he belonged.

Each Yemeni tribe has a "diwan", which constitutes a middle space between the tribe and the state, and a public space, which constitutes a space for deliberation on general issues for the tribe, making decisions related to resource management, and settling disputes between families and clans,[241] Through a consensual process that took place among members of the tribe.

Recently, the tribe's decision-making processes are no longer carried out through consensus. Rather, the sheikh is the one who makes most of the decisions, without referring to the tribe's audience. This is what stripped the tribe of its traditional civil character, strengthened its sectarian character, and hindered the development of modern civil society.

Marginalized groups[edit]

In the past, society used to look down on singers, but the matter has changed recently. Many of the Yemeni singers who have recently appeared belong to different societal groups and the lowest strata of the social ladder, what are known as The Marginalized[242][243] These customs no longer had their previous effect, or they remained only symbolic, while discrimination, marginalization, and contempt for the so-called Akhdam or marginalized people remained, reaching the point of physical attacks and ignoring the authorities. The tribal structure in Yemen continues to exist.[244][245] The situation of the Akhdams in Yemen is close to the Pariha in India[246] Al-Akhdam is often confused with slaves, but the truth is that those known as Al-Akhdam are not 'slaves' or Mamluks, nor were they. These divisions existed in North and South Yemen with different names. The synonym for "judges" in North Yemen (the late Ibrahim al-Hamdi belonged to them) are "Sheikhs" in the south and Hadramaut These divisions have ancient roots dating back to the history of Ancient Yemen. In Aden, things were different. Aden was a commercial city from its ancient times.[247] It was visited by merchants, and it was not known who its original inhabitants were. In the year 1872 the city's population was 19,289 of them were Arabs, 4,812 of whom were 965 of the original inhabitants of the city[248] and 8,168 Indians, of whom 2,557 were Muslims, and the rest were Africans (East Africa)[248] As for the religious level, marriage between Zaydiya and Shafi'i is common in Yemen.[249] As for Ismailis they intermarry among themselves and there is a very small Twelver minority whose existence is not recognized by the Yemeni government and they suffer from societal isolation as well.[250] Intermarriage between Yemeni Jews is socially rejected, primarily for religious factors. Even Yemeni Jews refuse to marry their daughters to Muslims, but they are socially and legally too weak to stop such marriages. In the past, before Islam, intermarriage and intermarriage with Jews was common in Yemen. Indeed, Yemeni Jews themselves are a mixture of Hebrews and tribes[251] Their presence is very ancient. They are the indigenous people of Yemen and do not differ from the tribesmen ethnically or racially, except for their religious belief and culture. However, Yemeni Jews are subjected to societal and political discrimination and marginalization, which was mentioned by Orientalists who visited Yemen in the twentieth century.

The Jews were skilled goldsmiths and among the best dagger makers, and they were also present in Aden where the English[246] but most of them moved to life in Israel and the United States in any case, small numbers of them remained and they had no significant societal or political influence at all. There are Yemenis of Turkish and Persian origins, unlike those of African origins. They have integrated into society faster, and there is no discrimination against Yemenis of Turkish origins at all[252] The difficult economic conditions that the country is going through contributed to in melting differences, not all the tribes in Yemen are like the tribes surrounding Sanaa, Amran governorate and Sanhan which saw themselves as participating with Ali Abdullah Saleh in rule. However, the discrimination that affects approximately five hundred thousand people to approximately one million people who are called the Muhamasheen or "Al-Akhdham" in further contempt for them still exists, and one chair was appointed for them in the Yemeni National Dialogue Conference, represented by the so-called Noman Al-Hudhaifi[253] A number of their kings wrote works on medicine, industry, and language.[254][255]

Political role[edit]

Throughout the history of the modern state and before it, the Yemeni tribe is considered politically important in building the state, and it forms part of its authority, and plays a major role in political decision-making, although it does not It has a vision for social transformation, but it has an influence in opposing or stopping every decision that conflicts with its interests. The expansion and effectiveness of the tribal role in Yemen has worked to strengthen tribal structures and adherence to the culture of privacy and unequal citizenship relations, which has remained one of the most important issues around which conflict between Modernization forces and traditional forces. This situation weakens the role of civil society and makes it unable to contribute to the process of democratic transformation because the traditional forces are considered conservative social forces resistant to change.

The tribe represents an essential component of social capital, and a living economic force whose influence extends to the relationship between the state and the tribe, and thus determines the level of institutionalization of the state, its ability to direct and make decisions, and the extent of implementing the rule of law.

The tribe in Yemen is viewed as a national entity from the point of view of those defending its existence in its current form. It is a major and ancient part of the components of the Yemeni people. Observers believe that Ali Abdullah Saleh used the tribe and directed it against civil values, until the civilization of civil society became mortgaged. In the hands of tribal sheikhs, Ali Abdullah Saleh's regime did not work for 33 years to establish the foundations of a civil society,[256] To improve the image of the regime, Ali Abdullah Saleh exaggerated in portraying the nature of the Yemeni tribes And to give it legitimacy before the international community,[257] Researcher Sarah Phillips believes that it may be believed that democracy in Yemen is more likely to succeed than in other Arab countries due to the egalitarian nature of the tribes, and their prevention of any authoritarian authority from tyranny in the country, but Ali Abdullah Saleh used the tribes in favor of consolidating the foundations of minority rule in the country.[258]

In the south and Hadramaut[edit]

After Captain Stafford Haines occupied Aden on 19 January 1839 he pursued a policy based on provoking tribes to fight among themselves, thus reducing his need for large British forces.[259] The occupation government agreed to this policy,[260] Haines and those who came after him succeeded in dividing The south and east of Yemen were divided into sheikhdoms, sultanates, emirates and states, the number of which reached 25 tribal states, all of which were linked to protection agreements with the colonial administration in Aden.[261]

When the South gained its independence in November 1967, the new state worked to eliminate the authority of the tribal sheikhs, and merged the tribal states into one national state. There was no prominent political tribal role, so the policies of The Yemeni Socialist Party is one of the reasons for state control and the absence of tribal authority in the south of the country before Yemeni unity in 1990. The ruling party succeeded in building a strong state controlling sources of income, but it was a closed totalitarian state, with Bad relations with most countries in the region as well as economic failure. As for the regions of Hadhramaut, the tribe's authority was at its lowest in the south because of the socialist policies, and because of the Hadrami diaspora in Southeast Asia, East Africa, and the Gulf. The Hadramis outside Hadramaut were more than those inside it. And the symbolism remained weak, but the tribe remains strong in areas in the south like Abyan and Shabwa. Al-Dhalea increased in strength after Yemeni unity and Summer War of 1994 to some extent, but it is not as strong and influential as the northern tribes.[262]

As for the state that was formed in the north after the 26 September Revolution it sought to include the tribal sheikhs in the political body of the state, and the Yemeni state in the north before unification witnessed a struggle between two military forces and the tribal sheikhs, until it created Ali Abdullah Saleh, who does not belong to a strong tribe and does not have long military experience, created a kind of balance and reconciliation between the tribal forces and the army at the beginning of his rule, but he began to change his positions in later periods and transformed the army into what could be called the "family sector."[263]

Yemen Arab Republic[edit]

Judge Abdul Rahman al-Eryani assumed the presidency after the dismissal of Abdullah Al-Sallal. They do not have the influence of the tribes around Sanaa, but the elites who belong to this governorate, such as Beit Al-Iryani, realize that it is in their interest to maintain good relations with the tribal elites because they lack a tribal base to support them.[264]

During the presidency of Judge Abd al-Rahman al-Iryani the military entered a party in political battles, starting with the conflict over the establishment of the National Council,[265] where the forces presented What were known as the correction decisions of the armed forces, the correction officers demanded that the funds provided by the state to the tribal sheikhs be stopped. In August 1971 the government resigned and Prime Minister Ahmed Mohamed Noman justified the government's resignation due to its inability to fulfill its obligations due to... Tribal sheikhs’ depletion of the state budget,[266][267][268] In December 1972 the resignation of the government of Mohsen Al-Aini due to... His demands, which were not met, were the dissolution of the Shura Council, which is dominated by sheikhs, the dissolution of the Tribal Affairs Authority, and the cessation of the sheikhs’ budget.[269]

The June 13 Corrective Movement was led by Lieutenant Colonel Ibrahim al-Hamdi, and President Ibrahim al-Hamdi overthrew Judge Abd al-Rahman al-Iryani by persuading Tribal leaders, and using them as a temporary bait to realize that they are the ones with the real power on the ground. So he wooed Sinan Abu Lahoum by appointing his relative Mohsen Al-Aini as head of the government and kept Abu Lahoum's relatives in the army, but he quickly got rid of them, and Al-Hamdi worked to reduce the role of tribal sheikhs in the army and the state and abolished Ministry of Tribal Affairs He froze the work of the constitution and dissolved the Shura Council, and on 27 July 1975 which he called "Army Day," he issued decisions to remove many tribal sheikhs from the leadership of the military establishment. Al-Hamdi moved Abdullah bin Hussein al-Ahmar even though he was a rival of Abu Lahoum, but he realized al-Hamdi's intentions to get rid of the mostly negative influence of tribal forces, angered[270] Al-Ahmar tried to rally his supporters in the countryside of Sanaa to overthrow President Al-Hamdi, but Saudi Arabia, the guardian of the tribal forces in Yemen, through the money it pays through the so-called "Special Committee"[271] I refused to support Al-Ahmar because Al-Hamdi succeeded in making them believe that he was their ally by getting rid of the Abu Lahoum family,[270] The era of Ibrahim al-Hamdi witnessed major political and economic reforms,[272] He bet on his popularity in Yemeni circles to remove his country from the Saudi mantle, by clipping the nails of powerful tribal players,[273] So he held a summit Quartet of [[Red Sea] Basin countries], and began communicating with the President of the People's Democratic Republic of Yemen Salem Rabie Ali regarding Yemeni unity, and concluded arms deals with France[274] Ibrahim al-Hamdi was assassinated in 1977 one day before he headed to Aden to discuss unity with President Salem Rabie Ali.[275]

After the assassination of Al-Hamdi, Ahmed Hussein Al-Ghashmi assumed the presidency, and the tribal sheikhs, Lieutenant General Hassan Al-Omari demanded their positions in the armed forces, including Mujahid Abu Shawarib and Abdullah Al-Ahmar and Sinan Abu Lahoum, which is what happened to them[276] They detailed the military units on tribal and regional basis.[276]

The period of Ali Abdullah Saleh[edit]

To strengthen the place of tribal sheikhs in power, in the eighties Ali Abdullah Saleh established the Tribal Affairs Authority to play the same role as the Ministry of Tribal Affairs, which was abolished by the assassinated President Ibrahim al-Hamdi, in organizing the distribution of funds.[277]

During the 1990s, Ali Abdullah Saleh chose the patronage system as a way to quickly bypass the difficult process of state-building. In the absence of strong state institutions, the political elite in the Saleh era formed a model of cooperative governance where competing interests agreed to discipline through implicit acceptance of the resulting balance, and this balance was not disturbed except after the efforts of Ali Abdullah Saleh to strengthen the position of his son Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh.[278] Saleh appointed his relatives to various military positions to ensure the loyalty of the institution, and in return he rewarded them in ways that included allowing them access to the government's foreign exchange reserves and showing them to deal in contraband on the black market, other relatives held ministerial positions related to planning, real estate and insurance and others took over public projects such as the National Oil Company and airlines, and rewarded others by granting them a monopoly on the tobacco trade and the construction of hotels.[279] His son Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh was the commander of the Yemeni Republican Guard, with approximately thirty thousand militants loyal to him.[280] According to the WikiLeaks document 05SANAA1352_a, General Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar and Yahya Muhammad Abdullah Saleh were involved in using military tankers to smuggle diesel to the Yemeni and Saudi markets,[281] Although the security services nominally report to the Ministries of Defense and Interior, senior leaders from Sanhan such as Ahmed Ali Abdullah Saleh, Yahya Muhammad Abdullah Saleh and Ali Mohsen al-Ahmar were largely independent in their actions, and there was virtually no civilian supervision of the army, so it became an important hotbed for patronage and the distribution of benefits, through fake soldiers and smuggling of weapons, fuel and people.[278]

Post-unity republic[edit]