The Rothschilds (film)

| The Rothschilds | |

|---|---|

| Directed by | Erich Waschneck |

| Written by | Gerhard T. Buchholz Mirko Jelusich C.M. Köhn |

| Produced by | C.M. Köhn (line producer) |

| Starring | See below |

| Cinematography | Robert Baberske |

| Edited by | Walter Wischniewsky |

| Music by | Johannes Müller |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | UFA |

Release date |

|

Running time | 97 minutes |

| Country | Nazi Germany |

| Language | German |

The Rothschilds (Die Rothschilds) is a 1940 Nazi German historical propaganda film directed by Erich Waschneck.

The film is also known as The Rothschilds' Shares in Waterloo (International recut version, English title). It portrays the role of the Rothschild family in the Napoleonic wars. The Jewish Rothschilds are depicted in a negative manner, consistent with the anti-Semitic policy of Nazi Germany.[1] The 1940 film has a similar title and a similar plot to a 1934 American film, The House of Rothschild, starring George Arliss and Boris Karloff, that presented the Rothschilds in a more positive light. It is one of three Nazi-era German films that provide an antisemitic retelling of an earlier film. The others, both released in 1940, bore titles similar to films released in 1934: The Eternal Jew was a documentary-format film with the same title as the 1934 film and Jud Süss was a drama based on a 1934 film adaptation of a 1925 novel.

Plot summary[edit]

As William I, Elector of Hesse refused to join the French supporting Confederation of the Rhine at its formation in 1806, he is threatened by Napoleon. In Frankfurt, he asks his agent Mayer Amschel Rothschild to convey bonds worth £600,000 he has received from Britain to subsidise his army to safety in England.

Rothschild however uses the money for his own ends, with the help of his sons, Nathan Rothschild in London and James Rothschild in Paris. They first use the money to finance Wellington's army in Spain's war against Napoleon, at advantageous terms of interest. In a notable coup, in 1815, Nathan spreads the rumour that Napoleon had won the Battle of Waterloo, causing London stock prices to collapse. He then bought a large quantity of equities at the bottom of the market, profiting handsomely as prices rose once the truth about the battle emerged. In a decade, the Rothschilds have accumulated a fortune of £11 million by using the Elector's money.

Nathan returns the original capital to the Elector, plus only a small amount of interest, keeping the great bulk of the profits for the Rothschilds, and plans to formalise a Europe wide network of family led financial institutions.

The film ends with a declaration that, as the film is released, the last Rothschild has left continental Europe as a refugee and the next target is England's plutocracy.

Cast[edit]

- Erich Ponto as Mayer Amschel Rothschild

- Carl Kuhlmann as Nathan Rothschild

- Herbert Hübner as Turner

- Albert Florath as Baring

- Hans Stiebner as Bronstein

- Walter Franck as Herries

- Waldemar Leitgeb as Wellington

- Hans Leibelt as King Louis XVIII

- Bernhard Minetti as Fouché

- Albert Lippert as James Rothschild

- Herbert Wilk as George Crayton

- Hilde Weissner as Sylvia Turner

- Ludwig Linkmann as Leib Herch

- Bruno Hübner as Ruthworth

- Rudolf Carl as Rubiner

- Michael Bohnen as Prince William IX

- Herbert Gernot as Clifford

- Theo Shall as Selfridge

- Ursula Deinert as Harriet

- Hubert von Meyerinck as Baron Vitrolles

Production[edit]

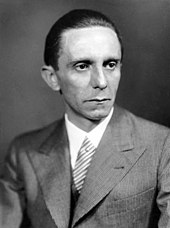

Goebbels ordered the beginning of the production on 17 November 1938.[2]

Background[edit]

Adolf Hitler believed that film was a potent tool for molding public opinion and the Nazis first established a film department in 1930. Three years later, on their rise to power, Propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels took an interest in using film to promote their philosophy and agenda and insisted that the role of the German cinema was the "vanguard of the Nazi military".[3]

The Nazis had hoped for a surge in antisemitic sentiment after Kristallnacht but, when it became clear that most Germans did not share such views, Goebbels ordered each studio to make an antisemitic film. While Hitler preferred presenting this agenda directly in films such as Der ewige Jude (The Eternal Jew), Goebbels preferred a more subtle approach of couching such messages in an engaging story with popular appeal.[4]

Saul Friedländer suggests that Goebbels' intent was to counter three films whose messages attacked the persecution of Jews throughout history by producing violently antisemitic versions of those films with identical titles.[5]

References[edit]

- ^ Waldman, Harry (2020-08-05). Nazi Films in America, 1933-1942. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9206-0.

- ^ Reeves, Nicholas (2004-03-01). Power of Film Propaganda. A&C Black. p. 112. ISBN 978-0-8264-7390-5.

- ^ Eisner, Lotte H. (29 September 2008). The Haunted Screen: Expressionism in the German Cinema and the Influence of Max Reinhardt. University of California Press. p. 329. ISBN 978-0-520-25790-0. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

- ^ Rees, Laurence (9 January 2006). Auschwitz: A New History. PublicAffairs. p. 16. ISBN 978-1-58648-357-9. Retrieved 8 November 2011.

- ^ Friedländer, Saul (1 April 2008). The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews, 1939-1945. HarperCollins. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-06-093048-6. Retrieved 11 November 2011.

External links[edit]

- The Rothschilds at IMDb

- The Rothschilds is available for free viewing and download at the Internet Archive (German dialogue, English subtitles)

- 1940 films

- 1940 drama films

- 1940s historical films

- German drama films

- German historical films

- Films of Nazi Germany

- 1940s German-language films

- Films directed by Erich Waschneck

- Nazi antisemitic propaganda films

- Films set in the 1800s

- Films set in the 1810s

- Films set in London

- Films set in Germany

- Films set in Spain

- Rothschild family

- German black-and-white films

- UFA GmbH films

- Films set in Frankfurt

- Cultural depictions of Arthur Wellesley, 1st Duke of Wellington

- Cultural depictions of Louis XVII

- Films set in Paris