The Boat Race 1970

| 116th Boat Race | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Date | 28 March 1970 | ||

| Winner | Cambridge | ||

| Margin of victory | 3+1⁄2 lengths | ||

| Winning time | 20 minutes 22 seconds | ||

| Overall record (Cambridge–Oxford) | 64–51 | ||

| Umpire | A. Burrough (Cambridge) | ||

| Other races | |||

| Reserve winner | Goldie | ||

| Women's winner | Cambridge | ||

| |||

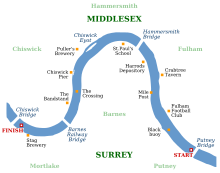

The 116th Boat Race took place on 28 March 1970. Held annually, it is a side-by-side rowing race between crews from the Universities of Oxford and Cambridge along the River Thames. It was won by Cambridge who passed the finishing post 3+1⁄2 lengths ahead of Oxford, securing Cambridge's third consecutive victory. The race was particularly notable for the "unorthodox" steering of the Oxford cox Ashton Calvert.

In the reserve race, Goldie beat Isis, and in the Women's Boat Race, Cambridge were victorious.

Background

[edit]The Boat Race is a side-by-side rowing competition between the boat clubs of University of Oxford (sometimes referred to as the "Dark Blues")[1] and the University of Cambridge (sometimes referred to as the "Light Blues").[1] The race was first held in 1829, and since 1845 has taken place on the 4.2-mile (6.8 km) Championship Course on the River Thames in southwest London.[2][3] The rivalry is a major point of honour between the two universities, as of 2014 it is followed throughout the United Kingdom and broadcast worldwide.[4][5][6] Cambridge went into the race as reigning champions, having beaten Oxford by four lengths in the previous year's race, and held the overall lead, with 63 victories to Oxford's 51 (excluding the "dead heat" of 1877).[7][8]

The first Women's Boat Race took place in 1927, but did not become an annual fixture until the 1960s. Up until 2014, the contest was conducted as part of the Henley Boat Races, but as of the 2015 race, it is held on the River Thames, on the same day as the men's main and reserve races.[9] The reserve race, contested between Oxford's Isis boat and Cambridge's Goldie boat has been held since 1965. It usually takes place on the Tideway, prior to the main Boat Race.[8]

The race was umpired by the former Cambridge University Boat Club president and rower Alan Burrough who took part in Cambridge's two losses in the 1937 and 1938 races and their victory in the 1939 race.[10][11] Burrough had also umpired the 1966 race. Oxford were coached by their former boat club president Iain Elliott who rowed for the Dark Blues in the 1960 and 1961 races,[12][13] and the Olympic rower Hugh "Jumbo" Edwards who had represented Oxford in the 1926 race.[12][14] Lou Barry coached the Cambridge crew.[15] Czechoslovakian international rower Bob Janoušek assessed both crews as "extremely fit" but "far from expert in rowing".[16]

Crews

[edit]The Cambridge crew weighed an average of 13 st 9.25 lb (86.5 kg), 1.25 pounds (0.6 kg) per rower more than their opponents.[17] The Light Blues featured just one former Blue in president David Cruttendon. However the Cambridge boat also included five members of the successful 1969 Goldie crew.[12] Oxford saw the return of five former Blues,[17] including the boat club president, Ashton Calvert, who coxed the boat.[18]

| Seat | Oxford |

Cambridge | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name | College | Weight | Name | College | Weight | |

| Bow | R. J. D. Gee | St John's | 13 st 8 lb | J. F. S. Hervey-Bathurst | 1st & 3rd Trinity | 13 st 1.5 lb |

| 2 | J. K. G. Dart | Christ Church | 12 st 10 lb | C. L. Baillieu | Jesus | 13 st 5 lb |

| 3 | D. M. Higgs ‡ | Balliol | 13 st 9 lb | A. C. Buckmaster | Clare | 13 st 8 lb |

| 4 | S. E. Wilmer | Christ Church | 13 st 11 lb | C. J. Rogridgues | Jesus | 13 st 2 lb |

| 5 | F. J. L. Dale | Keble | 13 st 11 lb | C. J. Dalley | Queens' | 14 st 5.5 lb |

| 6 | A. J. Hall | Keble | 15 st 7 lb | D. L. Cruttendon (P) | St Catharine's | 16 st 0 lb |

| 7 | N. D. C. Tee | Balliol | 12 st 4 lb | C. M. Lowe | Fitzwilliam | 13 st 7 lb |

| Stroke | W. R. C. Lonsdale | Keble | 13 st 10 lb | S. N. S. Robertson | Fitzwilliam | 12 st 3.5 lb |

| Cox | A. T. Calvert (P) | New College | 8 st 12 lb | N. G. Hughes | Queens' | 8 st 9 lb |

| Source:[17] (P) – Boat club president[19] ‡ Higgs replaced Robin Parish six days before the race.[20] | ||||||

Race

[edit]

Cambridge won the toss and elected to start from the Surrey station,[17] from which every crew had won since the 1961 race.[12] The race commenced five minutes later than the scheduled 4.35 p.m. start time,[12] with Oxford delaying their arrival at the stakeboat.[21] Cambridge made the better start and took an early lead.[21] The Light Blues were half-a-length up within a minute, and had doubled that by the time they passed Beverley Brook. Oxford's stroke Lonsdale increased their rating in an attempt to stay with Cambridge around the long Surrey bend and temporarily succeeded. Still a length up at Harrods Furniture Depository, the Cambridge cox steered wide and Oxford began to close the gap. At Hammersmith Bridge, Oxford were no more than a length behind, and "unorthodox tactics" employed by Ashton Calvert,[21] the cox, ensured an "exciting tactical battle" followed.[21] Calvert steered the Dark Blue boat inside the Cambridge line and "made for the Surrey shore" in a manoeuvre which Donald Legget,[22] writing in The Observer described as "the most extraordinary sight I have ever witnessed while rowing or coaching".[22] Ignoring the umpire's warnings, Calvert continued on this path for two minutes before returning to the Middlesex side of the river.[22] Despite remaining stroke for stroke, at Chiswick Eyot Cambridge pushed away and held a lead of nine seconds by Chiswick Steps. The lead had increased by two seconds at Barnes Bridge and Cambridge passed the finishing post eleven seconds ahead.[21] Cambridge won by 3+1⁄2 lengths in a time of 20 minutes 22 seconds.[17]

In the reserve race, Cambridge's Goldie beat Oxford's Isis by fourteen lengths, a record distance, in their fourth consecutive victory.[8] In the 25th running of the Women's Boat Race, Cambridge triumphed, their eighth consecutive victory.[8]

Reaction

[edit]Calvert stated after the race: "I could see it was murder in those waves ... I decided to try to panic Cambridge by close contact steering, breaking their rhythm and attacking when the stations levelled out beyond Chiswick Steps."[21] Opinion was divided on Calvert's tactics: The Observer's Legget claimed that Calvert "adopted quite the wrong tactics",[22] while Jim Railton of The Times suggested "Calvert's move may well prove to be the future tactics of other crews behind but in contact at Hammersmith Bridge on the Middlesex station in similar conditions."[21] He went on to say "Calvert's tactics nearly paid off and in the circumstances I consider he was justified in his actions."[21] John Rodda of The Guardian described Calvert's steering as "zig-zag" and while acknowledging the "bold imagination" involved, claimed the cox's manoeuvres were "futile".[23]

References

[edit]Bibliography

- Dodd, Christopher (1983). The Oxford & Cambridge Boat Race. Stanley Paul. ISBN 0-09-151340-5.

- Burnell, Richard (1979). One Hundred and Fifty Years of the Oxford and Cambridge Boat Race. Precision Press. ISBN 0-9500638-7-8.

Notes

- ^ a b "Dark Blues aim to punch above their weight". The Observer. 6 April 2003. Retrieved 11 September 2014.

- ^ Smith, Oliver (25 March 2014). "University Boat Race 2014: spectators' guide". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "The Course". The Boat Race Company Limited. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "Former Winnipegger in winning Oxford–Cambridge Boat Race crew". CBC News. 6 April 2014. Retrieved 20 August 2014.

- ^ "TV and radio". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 8 August 2016. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Markovits, Andrei; Rensmann, Lars (6 June 2010). Gaming the World: How Sports Are Reshaping Global Politics and Culture. Princeton University Press. pp. 287–288. ISBN 978-0-691-13751-3.

- ^ "Classic moments – the 1877 dead heat". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 24 September 2014. Retrieved 12 October 2014.

- ^ a b c d "Results". The Boat Race Company Limited. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ "A brief history of the Women's Boat Race". The Boat Race Company Limited. Archived from the original on 6 October 2014. Retrieved 5 July 2014.

- ^ Burrell, pp. 49, 75

- ^ Dodd, Christopher (13 August 2002). "Alan Burrough". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 September 2014.

- ^ a b c d e Legget, Donald (22 March 1970). "It's the Surrey side up". The Observer. p. 26.

- ^ Burnell, p. 79

- ^ Burnell, p. 72

- ^ Rodda, John (28 March 1970). "Cambridge favoured". The Guardian. p. 19.

- ^ Railton, Jim (25 March 1970). "Minor injuries could tip balance". The Times. No. 57827. p. 17.

- ^ a b c d e Burnell, p. 82

- ^ Quarrell, Rachel (25 March 2008). "Presidents forgo paddles in the Boat Race". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 30 September 2014.

- ^ Burnell, pp. 51–52

- ^ Railton, Jim (24 March 1970). "Oxford replace Parish". The Times. No. 57826. p. 15.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Railton, Jim (30 March 1970). "Calvert may be proved right". The Times. No. 57830. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d Legget, Donald (29 March 1970). "Cambridge again". The Observer. p. 20.

- ^ Rodda, John (30 March 1970). "Calvert move futile". The Guardian. p. 13.

External links

[edit]