Temporary Slavery Commission

| Part of a series on |

| Forced labour and slavery |

|---|

|

The Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC) was a committee of the League of Nations, inaugurated in 1924.

It was the first committee of the League of Nations to address the issue of slavery and slave trade, and followed on the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90.

The TSC conducted a global investigation concerning slavery, slave trade and forced labor, and recommended solutions to address the issues. Its work lay the ground for the 1926 Slavery Convention and influenced the modern definition of slavery and human exploitation.[1]

History

[edit]Background and foundation

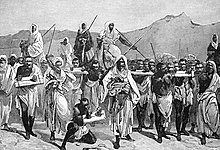

[edit]The TSC was preceded by the Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90, which had addressed slavery in a semi-global level via representatives of the colonial powers. It had concluded with the Brussels Conference Act of 1890. The 1890 Act was revised by the Convention of Saint-Germain-en-Laye 1919. After the League of Nations was founded in 1920, a need was felt to conduct an investigation of the existence of slavery and slave trade in the world on a global level, with the purpose of eradicating it where it existed.

The League of Nations conducted an informal investigation about the existence of slavery and slave trade in 1922–1923, gathering information from both governments as well as NGO's such as the Anti-Slavery Society and the Bureau international pour la défense des indigènes (International Bureau for the Defense of the Native Races, BIDI).[2] Both of the NGOs wanted a permanent anti-slavery office in Geneva. The colonial powers were slow to send enough information to form a report, which contributed to the decision to found a formal commission.[3]

The result of the report demonstrated the situation with chattel slavery in the Arabian Peninsula, Sudan and Tanganyika, as well as the illegal trafficking and force labor in the French colonies, South Africa, Portuguese Mozambique and Latin America.

However, governments and colonial authorities refused to accept information from private NGO's as official information from the League.

In December 1923, the League requested information from governments about the issue. When all governments answered with the reply that slavery did not exist within their territories, or had already been abolished, the League saw the need to establish a committee to conduct a formal investigation.[4]

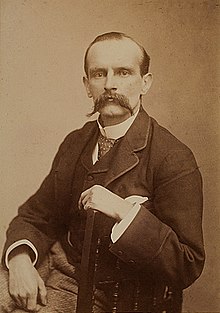

The Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC) was founded by the League in 1924 and held its first meeting in the summer of 1924. It was composed of eight expert members, among them Frederick Lugard, 1st Baron Lugard and Maurice Delafosse, Grimshaw, and Bellegarde, with Albrecht Gohr (Belgium) as chair and Freire d'Andrade as deputy.[5]

Activity

[edit]The TSC was to conduct a formal international investigation of all slavery and slave trade globally, and act for its total abolition. One of the issues was to create a formal definition of slavery.[6]

Every state previously known to have had slavery was encouraged to answer how they had combated it, which effects it had resulted in, and if they had considered further action, and to name individuals or organizations that could provide further information.[7]

At this point in time, chattel slavery was still legal in the Arabian Peninsula, such as in Saudi Arabia, in Yemen and in Oman, which was provided with slaves via foremost the Red Sea slave trade. The Mui tsai system in China attracted considerable attention in this time period.

Thirty-five states answered the Temporary Slavery Commission, but provided information of various quality: some were evidently lying, in some cases because colonial officials lied to their governments when providing information about their districts.[8] Slavery was claimed to have been eradicated in Bechuanaland.[9]

Africa

[edit]France stated to the Temporary Slavery Commission that all slaves in French West Africa were legally free since slavery had no legal basis, and that the slaves of the indigenous enslavers therefore remained with their former owners voluntarily.[10]

The Anglo-Egyptian Sudan had disbanded the Slavery Repression Department with the claim that slavery had become a marginal phenomenon.[11] The report on Sudan to the Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC) described the enslavement of Nilotic Non-Muslims of the South West by the Muslim Arabs in the North, where most agriculture was still managed by slave labor in 1923.[12]

The British colonial authorities actively fought the slave trade in Sudan but avoided addressing slavery itself for fear of causing unrest. The British allowed all slavery issued to be handled by the sharia courts which were controlled by the slave owning elite, which used Islamic law to control women, children and slaves. Slave raids were conducted from Ethiopia and Equatorial Africa and kidnapped people were exported to slavery in Arabia.[13]

The British agricultural officer P. W. Diggle conducted a personal campaign freeing slaves in Sudan. He was outraged in seeing slaves beaten, children taken from their parents and slave girls used for prostitution. Diggle was an important informer to the TSC about slavery in Sudan, which put pressure on the British in relation to the TSC.[14]

The British stated to Lugard of the TSC that it was not possible to abolish slavery in Sudan because of the massive risk for unrest in "so lightly held and explosive a country as the Sudan" where slavery was allowed per Islamic law. The British also presented a circular issued 6 May 1925 stating that all slaves born after 1898 were free by law and that slaves had the right to leave their owners and would not be returned if they did so, which gave the TSC the impression that action was taken by the British against slavery in Sudan.[15] It was soon found that the 6 May 1925 circular was in fact issued only to British officials and unknown to the Sudanese. When this fact was raised in the House of Lords, however, the colonial administration was ordered to publish and enforce the provisions against slavery in Sudan.[16] Furthermore, action was taken against the Red Sea slave trade via Sudan by taking better control of the Hajj pilgrimage and establishing a clearinghouse in Port Sudan for slaves repatriated by the British from slavery in the Kingdom of Hejaz, resulting in over 800 slaves resettled between 1925 and 1935.[17]

Ethiopia stated to the Temporary Slavery Commission that while slavery in Ethiopia was still legal, it was in a process of being phased out: that the slave trade was dying, that it was prohibited to sale, gift or will slaves, and that every child born to a slave after 1924 will be born free; that former slaves were to be sent back to their country of origin and that young ex-slaves were provided with education.[18]

During the Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC), a flourishing slave trade was discovered between Sudan and Ethiopia: slave raids were conducted from Ethiopia to the Funj and White Nile provinces in South Sudan, capturing Berta, Gumuz and Burun non-Muslims, who were bought from Ethiopian slave traders by Arab Sudanese Muslims in Sudan or across the border in the independent Empire of Ethiopia.[19]

The most prominent slave trader was Khojali al-Hassan, "Watawit" shaykh of Bela Shangul in Wallagi, and his principal wife Sitt Amna, who had been acknowledged by the British as the head of an administrative unit in Sudan in 1905. Khojali al-Hassan collected slaves – normally adolescent girls and boys or children – by kidnapping, debt servitude or as tribute from his feudal subjects, and would send them across the border to his wife, who sold them to buyers in Sudan.[20]

British Consul Hodson in Ethiopia reported that the 1925 edict had no practical effect on slavery and slave trade conducted across the Sudanese-Ethiopian border to Tishana: the Ethiopians demanded taxes and took children of people who could not pay and enslaved them; slave raids were still conducted against villages at nighttime by bandits burning huts, killing old and enslaving young. On one occasion in March 1925, when bandits were arrested, the government soldiers confiscated the 300 captured slaves and instead divided them as slaves to their soldiers; women and children were sold for a price of $15MT in Ethiopia, and the formal anti-slavery edict of 1925 was a mere formality.[21] In 1927, the slave trader Khojali al-Hassan, "Watawit" shaykh of Bela Shangul in Wallagi, was reported to have trafficked 13,000 slaves from Ethiopia to the Sudan via his wife Sitt Amna.[22]

The report on the Bechuanaland Protectorate to the Temporary Slavery Commission (TSC) described a form of slavery in Bechuanaland as "hereditary service" in which the tswana owned chattel slaves called malata (often of sarwa ethnicity) in a system called bolata among the ngwato-tswana. This was inheritable chattel slavery in which slaves were used as for example concubines, but slave trade was rare since it was rare to sell or buy a slave in contrast to inheriting one.[23]

Spain admitted that chattel slavery existed in Spanish Sahara but claimed that it was mainly an issue of house slaves and therefore mild, and that it was very difficult to address without causing instability; and that slave raids still occurred to provide slaves to the Trans-Saharan slave trade.[24]

Belgium admitted that indigenous African elites still kept chattel slaves in the Belgian colonies in Africa, but that they were generally well treated and not discontent, and that it was very difficult to address the issue without damaging the African economy, agriculture and food supply.[25]

Liberia stated that slavery was illegal but admitted that the ban was not enforced, but that slavery was dying.[26] The report of slavery in Liberia to the Temporary Slavery Commission described the trade in children sold as house slaves and women pawned as brides.[27]

Asia

[edit]Aden admitted that there was still chattel slavery in Yemen.[28]

The British admitted that chattel slavery still existed in remote areas of British India where the colonial authorities had little actual control, but that that the institution was clearly dying.[29]

In the report of slavery in Burma and India to the Temporary Slavery Commission, the British India Office stated that the slaves in Assam Bawi in Lushai Hills were now secured the right to by their freedom; that chattel slavery still existed in parts of Assam with weak British control; that the British negotiated with Hukawng Valley in Upper Burma to end slavery there, where the British provided loans for slaves to buy their freedom; that all slave trade had been banned, and that slavery in Upper Burma was expected to be effectively phased out by 1926.[30]

The Dutch estimated that chattel slavery may still exist in remote areas of the Dutch East Indies where Dutch control was only nominal, but that it was difficult to get access to information about the issue.[31]

The report of slavery in China to the Temporary Slavery Commission described the Mui Tsai trade in girls, which was a matter given international attention at this point.[32]

Hong Kong refused to provide any information with the motivation that there was no slavery in Hong Kong.[33]

Policy and conclusions

[edit]The final report of the TSC on 25 July 1925 recommended a new anti-slavery treaty and the abolition of slavery and slave trade.[34]

The TSC report concluded that by 1925, chattel slavery was abolished in all Christian majority countries and their colonies, as well as in China, Japan and Thailand, and that slavery in Nepal was planned to be banned soon, but that legal chattel slavery still existed in the Muslim states in the Arab Peninsula, such as the slavery in Hejaz, and that they should not be allowed to be members of the League of Nations unless they promised to ban slavery.[35]

The TSC addressed the definition of slavery, and advocated for the classification of forced labor as slavery since forced labor was in danger of being easily developed into slavery.[36] A difficulty for the TSC was the issue of forced labor, which was not defined as slavery but in some cases was close to it. The report of Portuguese Angola and Portuguese Mozambique to the Temporary Slavery Commission described how women and children were essentially taken hostage to coerce adult men into forced labor in the plantations of private officials and businessmen.[37] The TSC, particularly Grimshaw and Bellegarde, advocated for salaries to always be paid in money, to combat any tendencies for labor to transform into slave like conditions, and regarded forced labor as a form of slavery in disguise.[38]

As for slave trade, it was officially abolished in all territories under European control with the exception of the Sahara, were Muslim sects such as the Sanusi of Libya still operated the Trans-Saharan slave trade; that the Empire of Ethiopia still exported African slaves via the Red Sea slave trade across the Red Sea to Muslim lands of the Arabian Peninsula such as the Kingdom of Hijaz and the Aden Protectorate; that slave trade may still exist in China and Liberia, but that the British and French colonial authorities did fight the Red Sea slave trade with patrol boats.[39]

The TSC acknowledged concubinage in Islam as sexual slavery.[40]

The TSC filed their report to the League on 25 July 1925, after which it was disbanded. The TSC recommended that all legal chattel slavery and slave trade should be declared illegal; that slave trade by sea should be defined as piracy; that escaped slaves should be entitled to protection; that slave trade and slave raids should be criminalized, and that forced labor should be prohibited.[41]

Aftermath and legacy

[edit]The investigation by the TSC lay the foundation of the 1926 Slavery Convention.[42]

On 5 September 1929, the Sixth Commission of the League Assembly raised the need to evaluate the enforcement of the 1926 Slavery Convention, and the Committee of Experts on Slavery (CES) was created,[43] which in turn founded the first permanent slavery committee, the Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery (ACE).[44]

See also

[edit]- Brussels Anti-Slavery Conference 1889–90, 1889

- Committee of Experts on Slavery, 1932

- Advisory Committee of Experts on Slavery, 1933

- Ad Hoc Committee on Slavery, 1950

- Advisory Committee on Traffic in Women and Children

References

[edit]- ^ Allain, J. (2013). Slavery in International Law: Of Human Exploitation and Trafficking. Nederländerna: Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. p. 111-112

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 100-121

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 100-121

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 102-106

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 100-121

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 102

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 153-154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 102

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 154

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 174

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 175

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 161

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 109

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 152

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 109

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 101

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 120

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 110

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 109

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 113

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 114

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 110

- ^ [1] Gender and International Criminal Law. (2022). Storbritannien: OUP Oxford. 170

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 100-121

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 100-121

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. USA: AltaMira Press. 197-215

- ^ Miers, S. (2003). Slavery in the Twentieth Century: The Evolution of a Global Problem. Storbritannien: AltaMira Press. p. 216