Democratic socialism: Difference between revisions

Davide King (talk | contribs) →Europe: update Portugual |

|||

| Line 191: | Line 191: | ||

==== Americas ==== |

==== Americas ==== |

||

===== North America ===== |

===== North America ===== |

||

[[File:Sanders rally Council Bluffs IMG 4129 (49036408651).jpg|thumb|right|200px|Senator [[Bernie Sanders]], who described himself as a democratic socialist, presidential campaigns in [[Bernie Sanders 2016 presidential campaign|2016]] and [[Bernie Sanders 2020 presidential campaign|2020]] has attracted significant support from youth and working class group while realigning the [[Democratic Party (United States)|Democratic Party]] further to the left<ref name=BernieCon/>]] |

|||

{{see also|Socialism in Canada#"CCF to Victory", the rise of democratic socialism|History of the socialist movement in the United States|American Left#Social democratic and democratic socialist|l1=Democratic socialism in Canada|l3=Social democratic and democratic socialist parties in the United States}} |

{{see also|Socialism in Canada#"CCF to Victory", the rise of democratic socialism|History of the socialist movement in the United States|American Left#Social democratic and democratic socialist|l1=Democratic socialism in Canada|l3=Social democratic and democratic socialist parties in the United States}} |

||

In Canada, the democratic socialist [[Co-operative Commonwealth Federation]] (CCF), the precursor to the social democratic [[New Democratic Party (Canada)|New Democratic Party]] (NDP), had significant success in provincial politics. In 1944, the Saskatchewan CCF formed the first socialist government in North America and its leader [[Tommy Douglas]] is known for having spearheaded the adoption of Canada's nationwide system of universal healthcare called [[Medicare (Canada)|Medicare]]. At the federal level, the NDP was the [[Official Opposition (Canada)|Official Opposition]] from 2011 to 2015. |

In Canada, the democratic socialist [[Co-operative Commonwealth Federation]] (CCF), the precursor to the social democratic [[New Democratic Party (Canada)|New Democratic Party]] (NDP), had significant success in provincial politics. In 1944, the Saskatchewan CCF formed the first socialist government in North America and its leader [[Tommy Douglas]] is known for having spearheaded the adoption of Canada's nationwide system of universal healthcare called [[Medicare (Canada)|Medicare]]. At the federal level, the NDP was the [[Official Opposition (Canada)|Official Opposition]] from 2011 to 2015. |

||

{{anchor|Democratic socialism in the United States}} |

{{anchor|Democratic socialism in the United States}} |

||

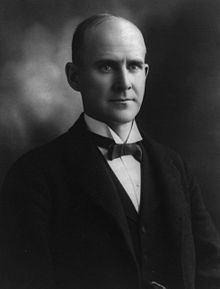

In the United States, [[Milwaukee]] has been led by a series of democratic socialist mayors in the early 20th century, namely [[Frank Zeidler]], [[Emil Seidel]] and [[Daniel Hoan]].<ref name="Ari Paul">Paul, Ari (19 November 2013). [https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/19/seattle-socialist-city-council-kshama-sawant "Seattle's election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America"]. ''[[The Guardian]]''. Retrieved 9 February 2014.</ref> In 2016, Vermont Senator [[Bernie Sanders]] made a bid for the [[2016 Democratic Party presidential candidates|Democratic Party presidential candidate]], thereby gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class,<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/bernie-sanders-just-changed-the-democratic-party|title=Bernie Sanders Just Changed the Democratic Party|first=John|last=Cassidy|work=The New Yorker|date=2 February 2016|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://theweek.com/articles/769073/bernie-sanders-conquered-democratic-party|title=Bernie Sanders has Conquered the Democratic Party|first=Jeff|last=Spross|work=The Week|date=24 April 2018|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48640268|title=Bernie Sanders: What's different this time around?|first=Anthony|last=Zurcher|publisher=BBC News|date=20 June 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> but he ultimately lost the nomination to [[Hillary Clinton]], a centrist candidate who was later defeated by [[Donald Trump]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/opinion/clinton-sanders-democratic-party.html|title=The Struggle Between Clinton and Sanders Is Not Over|last=Edsall|first=Thomas B.|work=The new York Times|date=7 September 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> Sanders described himself as a democratic socialist<ref name="politicosocialist">{{cite web|last=Lerer|first=Lisa|url=http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0709/25000.html|title=Where's the outrage over AIG bonuses?|date=16 July 2009|accessdate=19 April 2010 |work=[[Politico]]}}</ref><ref name="postsocialist">{{cite web|last=Powell|first=Michael|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/04/AR2006110401124.html|title=Exceedingly Social But Doesn't Like Parties|work=[[The Washington Post]]|date=6 November 2006|accessdate=26 November 2012}}</ref> and has also announced his intention to run for the [[2020 Democratic presidential primary]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vpr.org/post/hes-2020-bernie-sanders-running-president-again|title=He's In For 2020: Bernie Sanders Is Running For President Again|last=Kinzel|first=Bob|publisher=VPW News|date=19 February 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> |

In the United States, [[Milwaukee]] has been led by a series of democratic socialist mayors in the early 20th century, namely [[Frank Zeidler]], [[Emil Seidel]] and [[Daniel Hoan]].<ref name="Ari Paul">Paul, Ari (19 November 2013). [https://www.theguardian.com/commentisfree/2013/nov/19/seattle-socialist-city-council-kshama-sawant "Seattle's election of Kshama Sawant shows socialism can play in America"]. ''[[The Guardian]]''. Retrieved 9 February 2014.</ref> In 2016, Vermont Senator [[Bernie Sanders]] made a bid for the [[2016 Democratic Party presidential candidates|Democratic Party presidential candidate]], thereby gaining considerable popular support, particularly among the younger generation and the working class,<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.newyorker.com/news/john-cassidy/bernie-sanders-just-changed-the-democratic-party|title=Bernie Sanders Just Changed the Democratic Party|first=John|last=Cassidy|work=The New Yorker|date=2 February 2016|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref><ref name=BernieCon>{{cite news|url=https://theweek.com/articles/769073/bernie-sanders-conquered-democratic-party|title=Bernie Sanders has Conquered the Democratic Party|first=Jeff|last=Spross|work=The Week|date=24 April 2018|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref><ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-48640268|title=Bernie Sanders: What's different this time around?|first=Anthony|last=Zurcher|publisher=BBC News|date=20 June 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> but he ultimately lost the nomination to [[Hillary Clinton]], a centrist candidate who was later defeated by [[Donald Trump]].<ref>{{cite news|url=https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/07/opinion/clinton-sanders-democratic-party.html|title=The Struggle Between Clinton and Sanders Is Not Over|last=Edsall|first=Thomas B.|work=The new York Times|date=7 September 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> Sanders described himself as a democratic socialist<ref name="politicosocialist">{{cite web|last=Lerer|first=Lisa|url=http://www.politico.com/news/stories/0709/25000.html|title=Where's the outrage over AIG bonuses?|date=16 July 2009|accessdate=19 April 2010 |work=[[Politico]]}}</ref><ref name="postsocialist">{{cite web|last=Powell|first=Michael|url=https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2006/11/04/AR2006110401124.html|title=Exceedingly Social But Doesn't Like Parties|work=[[The Washington Post]]|date=6 November 2006|accessdate=26 November 2012}}</ref> and has also announced his intention to run for the [[2020 Democratic presidential primary]].<ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.vpr.org/post/hes-2020-bernie-sanders-running-president-again|title=He's In For 2020: Bernie Sanders Is Running For President Again|last=Kinzel|first=Bob|publisher=VPW News|date=19 February 2019|accessdate=25 November 2019}}</ref> |

||

Since his praise of the Nordic model indicated focus on [[social democracy]] as opposed to views involving [[social ownership]],<ref>Issenberg, Sasha (9 January 2010). [http://www.boston.com/news/nation/washington/articles/2010/01/09/sanders_a_growing_force_on_the_far_far_left/?page=1 "Sanders a growing force on the far, far left"]. ''[[Boston Globe]]''. Retrieved 24 August 2013. "You go to Scandinavia, and you will find that people have a much higher standard of living, in terms of education, health care, and decent paying jobs."</ref><ref>Sanders, Bernie (26 May 2013). [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rep-bernie-sanders/what-can-we-learn-from-de_b_3339736.html "What Can We Learn From Denmark?"]. ''[[The Huffington Post]]''. Retrieved 19 August 2013.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2016/02/01/how-much-of-a-socialist-is-sanders|title=How much of a socialist is Sanders?|work=[[The Economist]]|date=1 February 2016|accessdate=4 January 2019}}</ref> the [[Cato Institute]]'s Marian Tupy has argued that the term democratic socialism has become a misnomer for social democracy in American politics.<ref>{{cite web|last=Tupy|first=Marian|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/03/bernie-sanders-democratic-socialism/471630/|title=Bernie Is Not a Socialist and America Is Not Capitalist|work=[[The Atlantic]]|date=1 March 2016|accessdate=18 January 2019}}</ref> However, Sanders has explicitly advocated for some form of [[public ownership]],<ref>Kaczynski, Andrew; McDermott, Nathan (14 March 2019). [https://edition.cnn.com/2019/03/14/politics/kfile-bernie-nationalization/index.html "Bernie Sanders in the 1970s urged nationalization of most major industries"]. [[CNN]]. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref> [[workplace democracy]],<ref>Sanders, Bernie (2018). [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/download/workplace-democracy-act-2018?inline=file "Workplace Democracy Act"].</ref><ref>Elk, Mike (9 May 2018). [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/may/09/bernie-sanders-workplace-democracy-act-unions-teachers-strikes "Bernie Sanders introduces Senate bill protecting employees fired for union organizing"]. ''[[The Guardian]]''. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref><ref>Day, Meagan (14 May 2018). [https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/05/bernie-sanders-workplace-democracy-unions-legislation "A Line in the Sand"]. ''[[Jacobin (magazine)|Jacobin]]''. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref><ref>Goodner, David (6 March 2019). [https://www.commondreams.org/views/2019/03/07/will-2020-be-year-presidential-candidates-actually-take-labor-issues-seriously "Will 2020 Be the Year Presidential Candidates Actually Take Labor Issues Seriously?"]. [[Common Dreams]]. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref> an expansion of [[worker cooperative]]s<ref>[https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/recent-business/worker-owned-businesses-2014 "Worker-Owned Businesses"], [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/sanders-promotes-employee-ownership-as-alternative-to-greedy-corporations "Sanders Promotes Employee-Ownership as Alternative to Greedy Corporations"]. [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/legislative-package-introduced-to-encourage-employee-owned-companies-2019 "Legislative Package Introduced to Encourage Employee-Owned Companies"].</ref><ref> |

Since his praise of the Nordic model indicated focus on [[social democracy]] as opposed to views involving [[social ownership]],<ref>Issenberg, Sasha (9 January 2010). [http://www.boston.com/news/nation/washington/articles/2010/01/09/sanders_a_growing_force_on_the_far_far_left/?page=1 "Sanders a growing force on the far, far left"]. ''[[Boston Globe]]''. Retrieved 24 August 2013. "You go to Scandinavia, and you will find that people have a much higher standard of living, in terms of education, health care, and decent paying jobs."</ref><ref>Sanders, Bernie (26 May 2013). [http://www.huffingtonpost.com/rep-bernie-sanders/what-can-we-learn-from-de_b_3339736.html "What Can We Learn From Denmark?"]. ''[[The Huffington Post]]''. Retrieved 19 August 2013.</ref><ref>{{cite web|url=https://www.economist.com/democracy-in-america/2016/02/01/how-much-of-a-socialist-is-sanders|title=How much of a socialist is Sanders?|work=[[The Economist]]|date=1 February 2016|accessdate=4 January 2019}}</ref> the [[Cato Institute]]'s Marian Tupy has argued that the term democratic socialism has become a misnomer for social democracy in American politics.<ref>{{cite web|last=Tupy|first=Marian|url=https://www.theatlantic.com/international/archive/2016/03/bernie-sanders-democratic-socialism/471630/|title=Bernie Is Not a Socialist and America Is Not Capitalist|work=[[The Atlantic]]|date=1 March 2016|accessdate=18 January 2019}}</ref> However, Sanders has explicitly advocated for some form of [[public ownership]],<ref>Kaczynski, Andrew; McDermott, Nathan (14 March 2019). [https://edition.cnn.com/2019/03/14/politics/kfile-bernie-nationalization/index.html "Bernie Sanders in the 1970s urged nationalization of most major industries"]. [[CNN]]. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref> [[workplace democracy]],<ref>Sanders, Bernie (2018). [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/download/workplace-democracy-act-2018?inline=file "Workplace Democracy Act"].</ref><ref>Elk, Mike (9 May 2018). [https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2018/may/09/bernie-sanders-workplace-democracy-act-unions-teachers-strikes "Bernie Sanders introduces Senate bill protecting employees fired for union organizing"]. ''[[The Guardian]]''. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref><ref>Day, Meagan (14 May 2018). [https://www.jacobinmag.com/2018/05/bernie-sanders-workplace-democracy-unions-legislation "A Line in the Sand"]. ''[[Jacobin (magazine)|Jacobin]]''. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref><ref>Goodner, David (6 March 2019). [https://www.commondreams.org/views/2019/03/07/will-2020-be-year-presidential-candidates-actually-take-labor-issues-seriously "Will 2020 Be the Year Presidential Candidates Actually Take Labor Issues Seriously?"]. [[Common Dreams]]. Retrieved 20 July 2019.</ref> an expansion of [[worker cooperative]]s<ref>[https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/recent-business/worker-owned-businesses-2014 "Worker-Owned Businesses"], [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/sanders-promotes-employee-ownership-as-alternative-to-greedy-corporations "Sanders Promotes Employee-Ownership as Alternative to Greedy Corporations"]. [https://www.sanders.senate.gov/newsroom/press-releases/legislative-package-introduced-to-encourage-employee-owned-companies-2019 "Legislative Package Introduced to Encourage Employee-Owned Companies"].</ref><ref> |

||

Revision as of 13:31, 8 January 2020

| Part of a series on |

| Socialism |

|---|

|

Democratic socialism is a political philosophy that advocates for political democracy alongside a socially owned economy,[1] with a particular emphasis on workers' self-management and democratic control of economic institutions within a socialist market, or some form of a decentralised planned socialist economy.[2] Democratic socialists argue that capitalism is inherently incompatible with the values of freedom, equality and solidarity and that these ideals can only be achieved through the realisation of a socialist society.[3] Although most democratic socialists seek a gradual transition to socialism,[4] democratic socialism can support either revolutionary or reformist politics as means to establish socialism.[3] As a term, democratic socialism was popularised by social democrats who were opposed to the authoritarian development of socialism in Russia and elsewhere during the 20th century.[5][6]

The origins of democratic socialism can be traced to 19th-century utopian socialist thinkers and the British Chartist movement that somewhat differed in their goals yet all shared the essence of democratic decision making and public ownership of the means of production as positive characteristics of the society they advocated for.[7] In the late 19th century and early 20th century, democratic socialism was also influenced by social democracy. The gradualist form of socialism promoted by the British Fabian Society and Eduard Bernstein's evolutionary socialism in Germany influenced the development of democratic socialism.[8][9][10] Democratic socialism is what most socialists understand by the concept of socialism.[6][11] As a result, democratic socialism may be a very broad or more limited concept. It can refer to all forms of socialism that are democratic and reject an authoritarian Marxist–Leninist state[4][6][11][12] such as libertarian socialism,[13] reformist socialism[3] and revolutionary socialism[3][14][15] as well as ethical socialism,[16][17][18] liberal socialism,[17][19] social democracy[5][20][21][22][23][24][25][26] and some forms of democratic state socialism and utopian socialism.[7]

Democratic socialism is contrasted to Marxism–Leninism which is viewed as being authoritarian or undemocratic in practice.[11][12][27] Democratic socialists oppose the Stalinist political system and the Soviet-type economic system, rejecting the perceived authoritarian form of governance and the centralised administrative command economy that took form in the Soviet Union and other Marxist–Leninist states during the 20th century.[12] Democratic socialism is also distinguished from the Third Way on the basis that democratic socialists are committed to systemic transformation of the economy from capitalism to socialism whereas supporters of the centrist Third Way are opposed to ending capitalism.[21][23][24][25][26]

While having socialism as a long-term goal, modern social democrats are more concerned to curb capitalism's excesses and are supportive of progressive reforms to humanise it in the present day.[3][27] In contrast to that, democratic socialists believe that economic interventionism and other policy reforms aimed at addressing social inequalities and suppressing the economic contradictions of capitalism would only exacerbate the contradictions, causing them to emerge elsewhere in the economy under a different guise.[24][28][29][30][31][32][33] Democratic socialists believe the fundamental issues with capitalism are systemic in nature and can only be resolved by replacing the capitalist economic system with socialism, i.e. by replacing private ownership with collective ownership of the means of production and extending democracy to the economic sphere.[3][27][34]

Overview

Definition

| Part of a series on |

| Marxism |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Social democracy |

|---|

|

| Part of a series on |

| Libertarian socialism |

|---|

|

Democratic socialism is defined as having a socialist economy in which the means of production are socially and collectively owned or controlled, alongside a democratic political system of government.[1] Democratic socialism rejects self-described socialist states just as it rejects Marxism–Leninism.[3][11][12][27] As a result, Peter Hain classifies democratic socialism along with libertarian socialism as a form of anti-authoritarian socialism from below (using the term popularised by Hal Draper) in contrast to authoritarian socialism and state socialism. For Hain, this authoritarian/democratic divide is more important than the reformist/revolutionary divide.[13] In democratic socialism, it is the active participation of the population as a whole and workers in particular in the self-management of the economy that characterises socialism while centralised economic planning (whether coordinated by an elected government or not) and nationalisation do not represent socialism in itself.[3][11][12][27][35] A similar, more complex argument is made by Nicos Poulantzas.[36] Draper himself used the term revolutionary-democratic socialism as a type of socialism from below in The Two Souls of Socialism, writing that "the leading spokesman in the Second International of a revolutionary-democratic Socialism-from-Below [...] was Rosa Luxemburg, who so emphatically put her faith and hope in the spontaneous struggle of a free working class that the myth-makers invented for her a "theory of spontaneity".[14] Similarly, he wrote about Eugene V. Debs that "Debsian socialism" evoked a tremendous response from the heart of the people, but Debs had no successor as a tribune of revolutionary-democratic socialism".[15]

Democratic socialism has also been described as the form of social democracy prior to the 1970s, when the displacement of Keynesianism by neoliberalism and monetarism caused many social democratic parties to adopt the Third Way ideology, accepting capitalism as the current status quo and powers that be, redefining socialism in a way that it maintains the capitalist structure intact.[21][23][24][25][26] As an example, the new version of Clause IV of the New Labour constitution uses the term democratic socialism to describe a modernised form of social democracy. While affirming a commitment to democratic socialism,[37][38] it no longer definitely commits the party to public ownership of industry and in its place advocates "the enterprise of the market and the rigour of competition" along with "high quality public services [...] either owned by the public or accountable to them".[37] Much like modern social democracy, democratic socialism tends to follow a gradual, reformist or evolutionary path to socialism rather than a revolutionary one, a tendency that is captured in the statement of Labour Party revisionist Anthony Crosland, who argued that the socialism of the pre-war world was now becoming increasingly irrelevant.[39][40] This tendency is also often invoked in an attempt to distinguish democratic socialism from Marxist–Leninist socialism as in Norman Thomas' Democratic Socialism: A New Appraisal,[41] Roy Hattersley's Choose Freedom: The Future of Democratic Socialism,[42] Jim Tomlinson's Democratic Socialism and Economic Policy: The Attlee Years, 1945–1951[43] and Donald F. Busky's Democratic Socialism: A Global Survey.[11] A variant of this set of definitions is Joseph Schumpeter's argument set out in Capitalism, Socialism and Democracy (1941) that liberal democracies were evolving from liberal capitalism into democratic socialism with the growth of workers' self-management, industrial democracy and regulatory institutions.[44]

As a term, democratic socialism has some degree of significant overlaps on practical policy positions with social democracy, although they are often distinguished from each other.[3][27][34] Policies commonly supported by democratic socialists are Keynesian in nature, including significant economic regulation alongside a mixed economy, extensive social insurance schemes, generous public pension programs and a gradual expansion of public ownership over strategic industries.[20] Policies such as free universal healthcare and education are described as "pure Socialism" because they are opposed to "the hedonism of capitalist society".[45] Partly because of this overlap, some political commentators occasionally use the terms interchangeably.[46][47] One difference is that modern social democrats are mainly concerned with practical reforms to capitalism whereas democratic socialists ultimately want to go beyond mere meliorist reforms and advocate systemic transformation of the economy from capitalism to socialism.[3][27][34]

The section of social democracy that remained committed to the gradual abolition of capitalism as well as social democrats opposed to the centrist Third Way merged into democratic socialism. During the late 20th century, these labels were embraced, contested and rejected due to the development within the European left of Eurocommunism between the 1970s and 1980s, the rise of neoliberalism in the mid- to late 1970s, the fall of the Soviet Union in December 1991 and of Marxist–Leninist governments between 1989 and 1992, the rise and fall of the Third Way in the 1990s and 2000s and the rise of anti-austerity and Occupy movements in the late 2000s and early 2010s due to the global financial crisis of 2007–2008 and the Great Recession, the causes of which were widely attributed to the neoliberal shift and deregulation economic policies. This latest development contributed to the rise of politicians that represent a return to the post-war consensus social democracy such as Jeremy Corbyn in the United Kingdom and Bernie Sanders in the United States,[48] who assumed the label democratic socialist to describe their rejection of Third Way politicians that supported triangulation within the Labour and Democratic parties such as with New Labour and the New Democrats, respectively.[49][50]

Certain democratic socialists who come from Marxism emphasise Karl Marx's belief in democracy and call themselves democratic socialists.[51] The Socialist Party of Great Britain and the World Socialist Movement define socialism in its classical formulation as a "system of society based upon the common ownership and democratic control of the means and instruments for producing and distributing wealth by and in the interest of the community". Additionally, it includes statelessness, classlessness and the abolition of wage labour as characteristics of a socialist society. Although these characteristics are usually reserved to describe a communist society, this is consistent with Marx and Friedrich Engels' usage as they used to describe it with the terms socialism and communism interchangeably, characterising it as a stateless, propertyless, post-monetary economy based on calculation in kind, a free association of producers, workplace democracy and free access to goods and services produced solely for use and not for exchange.[52][53][54]

As a democratic socialist definition, the political scientist Lyman Tower Sargent proposes the following:

Democratic socialism can be characterised as follows:

- Much property held by the public through a democratically elected government, including most major industries, utilities, and transportation systems

- A limit on the accumulation of private property

- Governmental regulation of the economy

- Extensive publicly financed assistance and pension programs

- Social costs and the provision of services added to purely financial considerations as the measure of efficiency

Publicly held property is limited to productive property and significant infrastructure; it does not extend to personal property, homes, and small businesses. And in practice in many democratic socialist countries, it has not extended to many large corporations.[20]

Another example is the Democratic Socialists of America (DSA), with the organisation defining socialism as a decentralised socially-owned economy and rejecting centralised, Soviet-type economic planning, stating:

Social ownership could take many forms, such as worker-owned cooperatives or publicly owned enterprises managed by workers and consumer representatives. Democratic socialists favour as much decentralisation as possible. While the large concentrations of capital in industries such as energy and steel may necessitate some form of state ownership, many consumer-goods industries might be best run as cooperatives. Democratic socialists have long rejected the belief that the whole economy should be centrally planned. While we believe that democratic planning can shape major social investments like mass transit, housing, and energy, market mechanisms are needed to determine the demand for many consumer goods.[55]

The DSA has been critical of self-described socialist states, arguing that "[j]ust because their bureaucratic elites called them "socialist" did not make it so; they also called their regimes "democratic".[56] While ultimately committed to instituting socialism, the DSA focuses the bulk of its political activities on reforms within capitalism, arguing: "As we are unlikely to see an immediate end to capitalism tomorrow, DSA fights for reforms today that will weaken the power of corporations and increase the power of working people".[57]

Labour Party politician Peter Hain, who identify with libertarian socialism,[13][58] gives the following definition:

Democratic socialism should mean an active, democratically accountable state to underpin individual freedom and deliver the conditions for everyone to be empowered regardless of who they are or what their income is. It should be complemented by decentralisation and empowerment to achieve increased democracy and social justice. [...] Today democratic socialism's task is to recover the high ground on democracy and freedom through maximum decentralisation of control, ownership and decision making. For socialism can only be achieved if it springs from below by popular demand. The task of socialist government should be an enabling one, not an enforcing one. Its mission is to disperse rather than to concentrate power, with a pluralist notion of democracy at its heart.[59]

Tony Benn, another prominent left-wing Labour Party politician,[60][61] described democratic socialism as a socialism that is "open, libertarian, pluralistic, humane and democratic; nothing whatever in common with the harsh, centralised, dictatorial and mechanistic images which are purposely presented by our opponents and a tiny group of people who control the mass media in Britain".[62]

The term democratic socialism is sometimes used to refer to policies within capitalism as opposed to an ideology that aims to transcend and replace capitalism, although this is not always the case. Robert M. Page, a reader in Democratic Socialism and Social Policy at the University of Birmingham, wrote about transformative democratic socialism to refer to the politics of Labour Party Prime Minister Clement Attlee and its government (a strong welfare state, fiscal redistribution and some degree of public ownership) and revisionist democratic socialism as developed by Labour Party politician Anthony Crosland and Labour Party Prime Minister Harold Wilson, arguing:

The most influential revisionist Labour thinker, Anthony Crosland, contended that a more "benevolent" form of capitalism had emerged since the Second World War. [...] According to Crosland, it was now possible to achieve greater equality in society without the need for "fundamental" economic transformation. For Crosland, a more meaningful form of equality could be achieved if the growth dividend derived from effective management of the economy was invested in "pro-poor" public services rather than through fiscal redistribution.[63]

Some tendencies of democratic socialism advocate for revolution in order to transition to socialism, distinguishing it from some forms of social democracy.[64] The term democratic socialism can also be used to refer to a version of the Soviet Union model that was reformed in a democratic way. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev described perestroika as building a "new, humane and democratic socialism".[65] Consequently, some former communist parties have rebranded themselves as being democratic socialists.[46] This include parties such as The Left in Germany,[66][67] a party succeeding the Party of Democratic Socialism which was itself the legal successor of the Socialist Unity Party of Germany.[68]

Economics

Democratic socialists have promoted a variety of different models of socialism, ranging from market socialism where socially-owned enterprises operate in competitive markets and are self-managed by their workforce to non-market participatory socialism based on decentralised economic planning.[2][12]

Historically, democratic socialism has been committed to a decentralised form of economic planning where productive units are integrated into a single organisation and organised on the basis of self-management.[12] Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas, both of whom were United States presidential candidates for the Socialist Party of America, understood socialism to be an economic system structured upon production for use and social ownership in place of the for-profit system and private ownership of the means of production.[69][70]

Democratic socialists, especially contemporary proponents of market socialism, have argued that rather than socialism itself, the major reason for the economic shortcomings of Soviet-type economies was their failure to create rules and operational criteria for the efficient operation of state enterprises in their hierarchical administrative allocation of resources and commodities and the lack of democracy in the political systems that the Soviet-type economies were combined with.[71]

Philosophy

Philosophical support for democratic socialism can be found in the works of political philosophers such as Charles Taylor and Axel Honneth. Honneth has put forward the view that political and economic ideologies have a social basis, meaning they originate from intersubjective communication between members of a society. Honneth criticises the liberal state and ideology because it assumes that principles of individual liberty and private property are ahistorical and abstract when in fact they evolved from a specific social discourse on human activity. In contrast to liberal individualism, Honneth has emphasised the intersubjective dependence between humans, namely that human well-being depends on recognising others and being recognised by them. With an emphasis on community and solidarity, democratic socialism can be seen as a way of safeguarding this dependency.[72]

Some proponents of market socialism see it as an economic system compatible with the political ideology of democratic socialism.[73] Advocates of market socialism such as Jaroslav Vaněk argue that genuinely free markets are impossible under conditions of private ownership of productive property. Instead, he contends that the class differences and unequal distribution of income and economic power that result from private ownership of industry enable the interests of the dominant class to skew the market in their favour, either in the form of monopoly and market power, or by utilising their wealth and resources to legislate government policies that benefit their specific business interests. Additionally, Vaněk states that workers in a socialist economy based on cooperative and self-managed enterprises have stronger incentives to maximise productivity because they would receive a share of the profits based on the overall performance of their enterprise, in addition to receiving their fixed wage or salary.[74] Many pre-Marxian and proto-socialists were fervent anti-capitalists just as they were supporters of the free market,[75] including the British philosopher Thomas Hodgskin, the French mutualist thinker and anarchist philosopher Pierre-Joseph Proudhon and the American philosophers Benjamin Tucker and Lysander Spooner, among others. Although capitalism has been commonly conflated with the free market, there is a similar laissez-faire economic theory and system associated with socialism called laissez-faire socialism[76][77] to distinguish it from laissez-faire capitalism.[78][79][80]

One example of this democratic market socialist tendency is mutualism, a democratic and libertarian socialist theory developed by Proudhon in the 18th century, from which individualist anarchism emerged. Benjamin Tucker is one eminent American individualist anarchist, who adopted a left-wing laissez-faire system he termed anarchistic socialism as opposed to state socialism.[81][82] This tradition has been recently associated with contemporary scholars such as Kevin Carson,[83][84] Roderick T. Long,[85][86] Charles W. Johnson,[87] Brad Spangler,[88] Sheldon Richman,[89][90][91] Chris Matthew Sciabarra[92] and Gary Chartier,[93] who stress the value of radically free markets, termed freed markets to distinguish them from the common conception which these left-libertarians believe to be riddled with statist and bourgeois privileges.[94] Referred to as left-wing market anarchists[95] or market-oriented left-libertarians,[91] Proponents of this approach strongly affirm the classical liberal ideas of self-ownership and free markets while maintaining that taken to their logical conclusions these ideas support anti-capitalist, anti-corporatist, anti-hierarchical and pro-labour positions in economics, anti-imperialism in foreign policy and radically progressive views regarding sociocultural issues such as gender, sexuality and race.[96] Echoing the language of Tucker, Spooner and Hodgskin, among others, in maintaining that because of its heritage, emancipatory goals and potential, radical market anarchism should be seen by its proponents and by others as part of the socialist tradition and that market anarchists can and should call themselves socialists.[97] As a result, critics of the free market and laissez-faire as commonly understood argue that socialism is fully compatible with a market economy and that a truly free-market or laissez-faire system would be anti-capitalist and socialist in practice.[98][99] According to supporters, this would result in the socialist society as advocated by democratic and libertarian socialists alike, when socialism is not understood as state socialism and conflated with self-described socialist states and the terms free market and laissez-faire are understood to mean being free from all forms of economic privilege, monopolies and artificial scarcities, implying that economic rents, i.e. profits generated from a lack of perfect competition, must be reduced or eliminated as much as possible through free competition rather than free from regulation.[100]

David McNally, a professor at the University of Houston, has argued in the Marxist tradition that the logic of the market inherently produces inequitable outcomes and leads to unequal exchanges, writing that Adam Smith's moral intent and moral philosophy espousing equal exchange was undermined by the practice of the free market he championed as the development of the market economy involved coercion, exploitation and violence that Smith's moral philosophy could not counteract. McNally criticises market socialists for believing in the possibility of fair markets based on equal exchanges to be achieved by purging parasitical elements from the market economy such as private ownership of the means of production, arguing that market socialism is an oxymoron when socialism is defined as an end to wage labour.[101]

Tendencies

While the term socialism is frequently used to describe socialist states and Soviet-style economies, especially in the United States due to the First and Second Red Scares, democratic socialists use the term socialism to refer to their own tendency that rejects the ideas of authoritarian socialism and state socialism as socialism,[3][11][12][27] regarding them as a form of state capitalism in which the state undertakes commercial economic activity and where the means of production are organised and managed as state-owned enterprises, including the processes of capital accumulation, centralised management and wage labour. As a result, democratic socialism generally refers to socialists that are opposed to Marxism–Leninism and to a social democracy which is committed to the abolishment of capitalism in favour of socialism and the institution of a post-capitalist economy.[3][11][12][27]

Democratic socialism mainly refers to the anti-Leninist and anti-Stalinist left-wing,[3][11][12][27] especially anti-authoritarian socialism from below,[102] libertarian socialism,[13] market socialism,[2] Marxian socialism[12] and certain left communist and ultra-left tendencies such as councilism and communisation[13][36][14][15] as well as orthodox Marxist[103] tendencies related to Eduard Bernstein,[10] Karl Kautsky[104][105][106] and Rosa Luxemburg.[14] Democratic socialism also includes Eurocommunism, a trend originating between the 1950s and 1980s referring to communist parties that adopted democratic socialism after Nikita Khrushchev's de-Stalinisation in 1956 and all European communist parties since the 1990s.[46][47] In addition, some social democratic tendencies are also occasionally classified as democratic socialism.[11][39][40][41][42][43][103]

Social democracy is distinguished between the early and classical trend that supported revolutionary socialism, mainly socialism related to Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels as well as orthodox Marxism related to important social democratic politicians and Marxist thinkers like Kautsky, Luxemburg and Vladimir Lenin, including more democratic and libertarian interpretations of Leninism, the revisionist trend adopted by Bernstein and other reformist socialist leaders between the 1890s and 1940s, the post-war trend that adopted or endorsed Keynesian welfare capitalism[107][108] as part of a compromise between capitalism and socialism[109] and those opposed to the Third Way.[21][22][23][24][25][26]

Implementation

Although the term socialism is commonly used in the Anglosphere to describe Marxism–Leninism and affiliated states and governments, there have also been several anarchist and socialist societies that followed democratic socialist principles, encompassing anti-authoritarian, democratic anti-capitalism.[110] The most notable historical examples are the Paris Commune, the various soviet republics established in the post-World War I period, early Soviet Russia before the abolition of soviet councils by the Bolsheviks, Revolutionary Catalonia as noted by George Orwell[111] and more recently Rojava in northern Syria.[112] Other examples include the kibbutzim in modern-day Israel,[113] Marinaleda in Spain,[114] the Zapatistas of EZLN in Chiapas[115][116] and to some extent the workers' self-management policies within the Socialist Federal Republic of Yugoslavia and Cuba.[117] However, the best known example is that of Chile under President Salvador Allende, who was violently overthrown in a military coup funded and backed by the CIA in 1973.[118][119][120][121][122]

When nationalisation of large industries was relatively widespread during the Keynesian post-war consensus, it was not uncommon for some commentators to describe several European countries as democratic socialist states seeking to move their countries toward a socialist economy. In 1956, leading British Labour Party politician and author Anthony Crosland claimed that capitalism had been abolished in Britain, although others such as Welshman Aneurin Bevan, Minister of Health in the first post-war Labour government and the architect of the National Health Service, disputed the claim that Britain was a socialist state.[123][124] For Crosland and others who supported his views, Britain was a socialist state. According to Bevan, Britain had a socialist National Health Service which stood in opposition to the hedonism of Britain's capitalist society, arguing:

The National Health service and the Welfare State have come to be used as interchangeable terms, and in the mouths of some people as terms of reproach. Why this is so it is not difficult to understand, if you view everything from the angle of a strictly individualistic competitive society. A free health service is pure Socialism and as such it is opposed to the hedonism of capitalist society.[45]

When the British Labour Party and the French Socialist Party were in power during the post-war period, some commentators claimed that Britain and France were socialist countries and the same claim is now applied to Nordic countries who apply the Nordic model, although the laws of capitalism still operated fully as in the rest of Europe and private enterprise dominated the economy. In the 1980s, the government of President François Mitterrand aimed to expand dirigisme by attempting to nationalise all French banks, but this attempt faced opposition from the European Economic Community which demanded a capitalist free-market economy among its members. Nevertheless, public ownership in France and the United Kingdom during the height of nationalisation in the 1960s and 1970s never accounted for more than 15–20% of capital formation.[125]

The form of socialism practised by parties such as the Singaporean People's Action Party during its first few decades in power was of a pragmatic kind as it was characterised by its rejection of nationalisation. Despite this, the party still claimed to be a socialist party, pointing out its regulation of the private sector, activist intervention in the economy and its social policies as evidence of this claim.[126] Singaporean Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew stated that he has been influenced by the democratic socialist British Labour Party.[127]

These confusions and disputes are caused not only by the socialist definition, but by the capitalist definition as well. Although Christian democrats, social liberals, national and social conservatives tend to support social democratic policies and generally see capitalism compatible with a mixed economy, classical liberals, conservative liberals, liberal conservatives, neoliberals and right-libertarians define capitalism as the free market, supporting a small government, laissez-faire capitalist market economy while opposing social democratic policies as well as government regulation and economic interventionism, claiming that actually existing capitalism is corporatism, corporatocracy or crony capitalism.[128][129][130][131]

Socialism has often been erroneously conflated with an administrative command economy, authoritarian socialism, a big government, Marxist–Leninist states, Soviet-type economic planning, state interventionism and state socialism. Austrian School economists such as Friedrich Hayek and Ludwig von Mises continually used the term socialism as a synonym for central planning and state socialism, falsely conflating it with fascism, opposing social democratic policies and the welfare state.[132][133][134] This is especially true in the United States, where socialism has become a pejorative used by conservatives and libertarians to taint liberal and progressive policies, proposals and public figures.[135]

History

19th century

Socialist models and ideas espousing common or public ownership have existed since antiquity, but the first self-conscious socialist movements developed in the 1820s and 1830s. Western European social critics, including Robert Owen, Charles Fourier, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Louis Blanc, Charles Hall and Henri de Saint-Simon were the first modern socialists who criticised the excessive poverty and inequality generated by the Industrial Revolution. The term was first used in English in the British Cooperative Magazine in 1827 and came to be associated with the followers of the Owen such as the Rochdale Pioneers, who founded the co-operative movement. Owen's followers stressed both participatory democracy and economic socialisation in the form of consumer co-operatives, credit unions and mutual aid societies. In the case of the Owenites, they also overlapped with a number of other working-class movements such as the Chartists in the United Kingdom.[136]

Fenner Brockway identified three early democratic socialist groups during the English Civil War in his book Britain's First Socialists, namely the Levellers, who were pioneers of political democracy and the sovereignty of the people; the Agitators, who were the pioneers of participatory control by the ranks at their workplace; and the Diggers, who were pioneers of communal ownership, cooperation and egalitarianism.[137] The philosophy and tradition of the Diggers and the Levellers was continued in the period described by E. P. Thompson in The Making of the English Working Class by Jacobin groups like the London Corresponding Society and by polemicists such as Thomas Paine. Their concern for both democracy and social justice marked them out as key precursors of democratic socialism.[138][139][140] Democratic socialism also has its origins in the Revolutions of 1848 and the French Democratic Socialists, although Karl Marx disliked the movement because he viewed it as a party dominated by the middle class and associated to them the word Sozialdemokrat, the first recorded use of the term social democracy.[141]

The Chartists gathered significant numbers around the People's Charter of 1838 which demanded the extension of suffrage to all male adults. Leaders in the movement also called for a more equitable distribution of income and better living conditions for the working classes. The very first trade unions and consumers' cooperative societies also emerged in the hinterland of the Chartist movement as a way of bolstering the fight for these demands.[142] The first advocates of socialism favoured social levelling in order to create a meritocratic or technocratic society based on individual talent as opposed to aristocratic privilege. Saint-Simon is regarded as the first individual to coin the term socialism.[143] Saint-Simon was fascinated by the enormous potential of science and technology and advocated a socialist society that would eliminate the disorderly aspects of capitalism and would be based on equal opportunities.[144] He advocated the creation of a society in which each person was ranked according to his or her capacities and rewarded according to his or her work.[143] The key focus of Saint-Simon's socialism was on administrative efficiency and industrialism and a belief that science was the key to the progress of human civilisation.[145] This was accompanied by a desire to implement a rationally organised economy based on planning and geared towards large-scale scientific progress and material progress, embodying a desire for a more directed or planned economy.[143] The British political philosopher John Stuart Mill also came to advocate a form of economic socialism within a liberal context. In later editions of Principles of Political Economy (1848), Mill would argue that "as far as economic theory was concerned, there is nothing in principle in economic theory that precludes an economic order based on socialist policies".[146][147]

In the United Kingdom, the democratic socialist tradition was represented by William Morris's Socialist League and in the 1880s by the Fabian Society and later the Independent Labour Party founded by Keir Hardie in the 1890s, of which writer George Orwell would later become a prominent member.[148] In the early 1920s, the guild socialism of G. D. H. Cole attempted to envision a socialist alternative to Soviet-style authoritarianism while council communism articulated democratic socialist positions in several respects, notably through renouncing the vanguard role of the revolutionary party and holding that the system of the Soviet Union was not authentically socialist.[149]

The Fabian Society is a British socialist organisation which was established with the purpose of advancing the principles of socialism via gradualist and reformist means.[150] The society laid many of the foundations of the Labour Party and subsequently affected the policies of states emerging from the decolonisation of the British Empire, most notably India and Singapore. Originally, the Fabian Society was committed to the establishment of a socialist economy, alongside a commitment to British imperialism and colonialism as a progressive and modernising force.[151] Today, the society functions primarily as a think tank and is one of the fifteen socialist societies affiliated with the Labour Party. Similar societies exist in Australia (the Australian Fabian Society), in Canada (the Douglas-Coldwell Foundation and the now disbanded League for Social Reconstruction) and in New Zealand. In 1889 (the centennial of the French Revolution of 1789), the Second International was founded, with 384 delegates from twenty countries representing about 300 labour and socialist organisations.[152] It was termed the Socialist International and Friedrich Engels was elected honorary president at the third congress in 1893. Anarchists were ejected and not allowed in mainly due to pressure from Marxists.[153] It has been argued that at some point the Second International turned "into a battleground over the issue of libertarian versus authoritarian socialism. Not only did they effectively present themselves as champions of minority rights; they also provoked the German Marxists into demonstrating a dictatorial intolerance which was a factor in preventing the British labour movement from following the Marxist direction indicated by such leaders as H. M. Hyndman".[153]

In Germany, democratic socialism became a prominent movement at the end of the 19th century, when the Eisenach's Social Democratic Workers' Party of Germany merged with Lassalle's General German Workers' Association in 1875 to form the Social Democratic Party of Germany. Reformism arose as an alternative to revolution, with leading social democrat Eduard Bernstein proposing the concept of evolutionary socialism. Revolutionary socialists, encompassing multiple social and political movements that may define revolution differently from one another, quickly targeted the nascent ideology of reformism and Rosa Luxemburg condemned Bernstein's Evolutionary Socialism in her 1900 essay titled Social Reform or Revolution? The Social Democratic Party of Germany became the largest and most powerful socialist party in Europe despite being an illegal organisation until the anti-socialist laws were officially repealed in 1890. In the 1893 federal elections, the party gained about 1,787,000 votes, a quarter of the total votes cast according to Engels. In 1895, the year of his death, Engels highlighted The Communist Manifesto's emphasis on winning as a first step the "battle of democracy".[154]

In his introduction to the 1895 edition of Karl Marx's The Class Struggles in France, Engels attempted to resolve the division between gradualist reformists and revolutionaries in the Marxist movement by declaring that he was in favour of short-term tactics of electoral politics that included gradualist and evolutionary socialist policies while maintaining his belief that revolutionary seizure of power by the proletariat should remain a key goal of the socialist movement. In spite of this attempt by Engels to merge gradualism and revolution, his effort only diluted the distinction of gradualism and revolution and had the effect of strengthening the position of the revisionists. Engels' statements in the French newspaper Le Figaro in which he argued that "revolution" and the "so-called socialist society" were not fixed concepts, but rather constantly changing social phenomena and said that this made "us [socialists] all evolutionists", increased the public perception that Engels was gravitating towards evolutionary socialism. Engels also wrote that it would be "suicidal" to talk about a revolutionary seizure of power at a time when the historical circumstances favoured a parliamentary road to power which he predicted could happen "as early as 1898".[155]

Engels' stance of openly accepting gradualist, evolutionary and parliamentary tactics while claiming that the historical circumstances did not favour revolution caused confusion among political commentators and the public. Bernstein interpreted this as indicating that Engels was moving towards accepting parliamentary reformist and gradualist stances, but he ignored that Engels' stances were tactical as a response to the particular circumstances at that time and that Engels was still committed to revolutionary socialism. As a result, Engels was deeply distressed when he discovered that his introduction to a new edition of The Class Struggles in France had been edited by Bernstein and Karl Kautsky in a manner which left the impression that he had become a proponent of a peaceful road to socialism.[156] On 1 April 1895, four months before his death, Engels wrote to Kautsky as follows:

I was amazed to see today in the Vorwärts an excerpt from my 'Introduction' that had been printed without my knowledge and tricked out in such a way as to present me as a peace-loving proponent of legality quand même [literally "come what may", but better translated as "at all costs"]. Which is all the more reason why I should like it to appear in its entirety in the Neue Zeit in order that this disgraceful impression may be erased. I shall leave Liebknecht in no doubt as to what I think about it and the same applies to those who, irrespective of who they may be, gave him this opportunity of perverting my views and, what's more, without so much as a word to me about it.[157]

Early 20th century

The socialist industrial unionism of Daniel DeLeon in the United States represented another strain of early democratic socialism in this period. It favoured a form of government based on industrial unions, but it also sought to establish a socialist government after winning at the ballot box.[158] Democratic socialism continued to flourish in the Socialist Party of America, especially under the leadership of Norman Thomas.[159] The Socialist Party of America was formed in 1901 after a merger between the three-year-old Social Democratic Party of America and disaffected elements of the Socialist Labor Party of America which had split from the main organisation in 1899.[160] Eugene V. Debs twice won over 900,000 votes in the 1912 presidential elections and increased his portion of the popular vote to over 1,000,000 in the 1920 presidential election despite being imprisoned for alleged sedition. The party also elected two Representatives (Victor L. Berger and Meyer London), dozens of state legislators, more than hundred mayors and countless minor officials.[161] In Argentina, the Socialist Party of Argentina was established in the 1890s, being led by Juan B. Justo and Nicolás Repetto, among others, becoming the first mass party in the country and in Latin America. The party affiliated itself with the Second International.[162]

Between 1924 and 1940, the Argentine Socialist Party was a member of the Labour and Socialist International (LSI).[163] In 1904, Australians elected Chris Watson as the first Prime Minister from the Australian Labor Party, becoming the first democratic socialist elected into office. The British Labour Party first won seats in the House of Commons in 1902. The International Socialist Commission (ISC) was formed in February 1919 at a meeting in Bern, Switzerland by parties that wanted to resurrect the Second International.[164] By 1917, the patriotism of World War I changed into political radicalism in most of Europe, the United States and Australia. Other socialist parties from around the world who were beginning to gain importance in their national politics in the early 20th century included the Italian Socialist Party, the French Section of the Workers' International, the Spanish Socialist Workers' Party, the Swedish Social Democratic Party, the Russian Social Democratic Labour Party, the Socialist Party of America in the United States and the Chilean Socialist Workers' Party.

In February 1917, revolution broke out in Russia in which workers, soldiers and peasants established soviets, the monarchy was forced into exile fell and a provisional government was formed until the election of a constituent assembly. Alexander Kerensky, a Russian lawyer and revolutionary, became a key political figure in the Russian Revolution of 1917. After the February Revolution, he joined the newly formed Russian Provisional Government, first as Minister of Justice, then as Minister of War and after July as the government's second Minister-Chairman. A leader of the moderate-socialist Trudovik faction of the Socialist Revolutionary Party, he was also the vice-chairman of the powerful Petrograd Soviet. After failing to sign a peace treaty with the German Empire which led to massive popular unrest against Kerensky's cabinet, his government was overthrown on 7 November by the Bolsheviks led by Vladimir Lenin in the October Revolution. Soon after the October Revolution, the Constituent Assembly elected Socialist-Revolutionary leader Victor Chernov as President of a Russian Republic, but it rejected the Bolshevik proposal that endorsed the Soviet decrees on land, peace and workers' control and acknowledged the power of the Soviets of Workers', Soldiers' and Peasants' Deputies. As a result, the Bolsheviks declared on the next day that the assembly was elected based on outdated party lists[165] and the All-Russian Central Executive Committee of the Soviets promptly dissolved it.[166][167]

At a conference held on 27 February 1921 in Vienna, parties which did not want to be a part of the Communist International or the resurrected Second International formed the International Working Union of Socialist Parties (IWUSP).[168] The ISC and the IWUSP eventually joined to form the LSI in May 1923 at a meeting held Hamburg.[169] Left-wing groups which did not agree to the centralisation and abandonment of the soviets by the Bolshevik Party led left-wing uprisings against the Bolsheviks. Such groups included Socialist-Revolutionary Party,[170] Left Socialist-Revolutionaries, Mensheviks and anarchists.[171] Amidst this left-wing discontent, the most large-scale events were the workers' Kronstadt rebellion[172][173][174] and the anarchist led Revolutionary Insurrectionary Army of Ukraine uprising which controlled an area known as the Free Territory.[175][176][177]

In 1922, the 4th World Congress of the Communist International took up the policy of the united front, urging communists to work with rank and file social democrats while remaining critical of their party leaders, whom they criticised for betraying the working class by supporting the war efforts of their respective capitalist classes. For their part, the social democrats pointed to the dislocation and chaos caused by revolution and later the growing authoritarianism of the communist parties after they achieved power. When the Communist Party of Great Britain applied to affiliate with the Labour Party in 1920, it was turned down. On seeing the Soviet Union's growing coercive power in 1923, a dying Lenin stated that Russia had reverted to a "bourgeois tsarist machine [...] barely varnished with socialism".[178] After Lenin's death in January 1924, the communist party, increasingly falling under the control of Joseph Stalin, rejected the theory that socialism could not be built solely in the Soviet Union in favour of the concept of socialism in one country.[179]

In other parts of Europe, many democratic socialist parties were united in the IWUSP in the early 1920s and in the London Bureau in the 1930s, along with many other socialists of different tendencies and ideologies. These socialist internationals sought to steer a centrist course between the revolutionaries and the social democrats of the Second International and the perceived anti-democratic Communist International. In contrast, the social democrats of the Second International were seen as insufficiently socialist and had been compromised by their support for World War I. The key movements within the IWUSP were the Independent Labour Party and the Austromarxists while the main forces in the London Bureau were the Independent Labour Party and the Workers' Party of Marxist Unification.[180][181]

Mid-20th century

After World War II, democratic socialist, labourist and social democratic governments introduced social reforms and wealth redistribution via welfare state social programmes and progressive taxation. Those parties dominated post-war politics in countries such as the Belgium, Czechoslovakia, France, Italy, the Nordic countries and the United Kingdom. At one point, France claimed the world's most state-controlled capitalist country, starting a period of unprecedented economic growth known as the Trente Glorieuses, part of the post-war economic boom set in motion by the Keynesian consensus. The public utilities and industries nationalised by the French government included Air France, the Bank of France, Charbonnages de France, Électricité de France, Gaz de France and Régie Nationale des Usines Renault.[182]

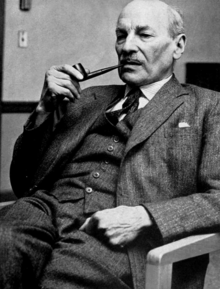

In 1945, the British Labour Party led by Clement Attlee was elected to office based on a radical, democratic socialist programme. The Labour government nationalised major public utilities and industries such as mining, gas, coal, electricity, rail, iron, steel and the Bank of England. British Petroleum was officially nationalised in 1951.[183] In 1956, Anthony Crosland stated that at least 25% of British industry was nationalised and that public employees, including those in nationalised industries, constituted a similar proportion of the country's total workforce.[184] The 1964–1970 and 1974–1979 Labour governments strengthened the policy of nationalisation.[185] These Labour governments renationalised steel (British Steel) in 1967 after the Conservatives had privatised it and nationalised car production (British Leyland) in 1976.[186] The 1945–1951 Labour government aso established National Health Service which provided taxpayer-funded health care to Every British citizen, free at the point of use.[187] High-quality housing for the working class was provided in council housing estates and university education became available to every citizen via a school grant system.[188]

During most of the post-war era, democratic socialist, labourist and social democratic parties dominated the political scene and laid the ground to universalistic welfare states in the Nordic countries. For much of the mid- and late 20th century. Sweden was governed by the Swedish Social Democratic Party largely in cooperation with trade unions and industry.[189]

Tage Erlander was the leader of the Social Democratic Party and led the government from 1946 until 1969, an uninterrupted tenure of twenty-three years, one of the longest in any democracy. From 1945 until 1962, the Norwegian Labour Party held an absolute majority in the parliament led by Einar Gerhardsen, who served Prime Minister for seventeen years. The Danish Social Democrats governed Denmark for most of the 20th century and since the 1920s and through the 1940s and the 1970s a large majority of Prime Ministers were members of the Social Democrats, the largest and most popular political party in Denmark. This particular adaptation of the mixed-market economy, better known as the Nordic model, is characterised by more generous welfare states (relative to other developed countries) which are aimed specifically at enhancing individual autonomy, ensuring the universal provision of basic human rights and stabilising the economy. It is distinguished from other welfare states with similar goals by its emphasis on maximising labour force participation, promoting gender equality, egalitarian and extensive benefit levels, large magnitude of redistribution and expansionary fiscal policy.[190]

Earlier in the 1950s, popular socialism emerged as a vital current of the left in Nordic countries could be characterised as a democratic socialism in the same vein as it placed itself between communism and social democracy.[191]

In countries like Sweden, the Rehn–Meidner model was adopted by the Swedish Social Democratic Party in the 1940s. This economic model allowed capitalists who owned very productive and efficient firms to retain excess profits at the expense of the firm's workers, exacerbating income inequality and causing workers in these firms to agitate for a better share of the profits in the 1970s. Women working in the state sector also began to assert pressure for better and equal wages.[192] In 1976, economist Rudolf Meidner established a study committee that came up with a proposal called the Meidner Plan which entailed the transferring of the excess profits into investment funds controlled by the workers in said efficient firms, with the goal that firms would create further employment and pay workers higher wages in return rather than unduly increasing the wealth of company owners and managers.[193] Capitalists immediately denounced the proposal as socialism and launched an unprecedented opposition and smear campaign against it, threatening to terminate the class compromise established in the 1938 Saltsjöbaden Agreement.[194] Prominent Swedish Prime Minister Olof Palme identified himself as a democratic socialist.[195]

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 was a spontaneous nationwide revolt by democratic socialists against the Marxist–Leninist government of the People's Republic of Hungary and its dictatorial Stalinist policies of repression, lasting from 23 October until 10 November 1956. Soviet leader Nikita Khrushchev's denunciation of the excesses of Stalin's regime during the 20th Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union that same year[196] as well as the revolt in Hungary[197][198][199][200] produced ideological fractures and disagreements within the communist and socialist parties of Western Europe. During India's freedom movement and fight for independence, many figures in the leftist faction of the Indian National Congress organised themselves as the Congress Socialist Party. Their politics and those of the early and intermediate periods of Jayaprakash Narayan's career combined a commitment to the socialist transformation of society with a principled opposition to the one-party authoritarianism they perceived in the Stalinist model.[201][202]

In the post-war years, socialism became increasingly influential throughout the so-called Third World after decolonisation. Embracing a new ideology called Third World socialism, countries in Africa, Asia and Latin America often nationalised industries held by foreign owners. In addition, the New Left, a movement composed of activists, educators, agitators and others who sought to implement a broad range of social reforms on issues such as gay rights, abortion, gender roles and drugs,[203] in contrast to earlier leftist or Marxist movements that had taken a more vanguardist approach to social justice and focused mostly on labour unionisation and issues related to class, became prominent in the 1960s and 1970s.[204][205][206] The New Left rejected involvement with the labour movement and Marxism's historical theory of class struggle.[207] In the United States, the New Left was associated with the anti-war and hippie movements as well as the black liberation movements such as the Black Panther Party.[208] While initially formed in opposition to the so-called Old Left of the Democratic Party, groups composing the New Left gradually became central players in the Democratic coalition, culminating in the nomination of George McGovern as the Democratic Party's candidate for President in 1972.[203]

The protest wave of 1968 represented a worldwide escalation of social conflicts, predominantly characterised by popular rebellions against military dicatorships, capitalists and bureaucratic elites, who responded with an escalation of political repression and authoritarianism. These protests marked a turning point for the civil rights movement in the United States which produced revolutionary movements like the Black Panther Party. The prominent civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. organised the Poor People's Campaign to address issues of economic and social justice[209] while personally showing sympathy with democratic socialism.[210]

In reaction to the Tet Offensive, protests also sparked a broad movement in opposition to the Vietnam War all over the United States and even into London, Paris, Berlin and Rome. Mass socialist or communist movements grew not only in the United States, but also in most European countries. The most spectacular manifestation of this were the May 1968 protests in France in which students linked up with strikes of up to ten million workers and for a few days the movement seemed capable of overthrowing the government. In many other capitalist countries, struggles against dictatorships, state repression and colonisation were also marked by protests in 1968, such as the beginning of the Troubles in Northern Ireland, the Tlatelolco massacre in Mexico City and the escalation of guerrilla warfare against the military dictatorship in Brazil. Countries governed by Marxist–Leninist parties had protests against bureaucratic and military elites. In Eastern Europe, there were widespread protests that escalated particularly in the Prague Spring in Czechoslovakia. In response, the Soviet Union occupied Czechoslovakia, but the occupation was denounced by the Italian and French communist parties as well as the Communist Party of Finland.[211]

Late 20th century

In Latin America, liberation theology s a socialist tendency within the Roman Catholic Church that emerged in the 1960s.[213][214] In Chile, Salvador Allende, a physician and candidate for the Socialist Party of Chile, became the first democratically elected Marxist President after presidential elections were held in 1970. However, his government was ousted three years later in a military coup backed by the CIA and the United States government, instituting the right-wing dictatorship of Augusto Pinochet which lasted until the late 1980s.[215] n addition, Michael Manley, a self-described democratic socialist, served as the fourth Prime Minister of Jamaica from 1972 to 1980 and from 1989 to 1992. According to opinion polls, he remains one of Jamaica's most popular Prime Ministers since independence.[216]

Eurocommunism became a trend in the 1970s and 1980s in various Western European communist parties which intended to develop a modernised theory and practice of social transformation that was more relevant for a Western European country and less aligned to the influence or control of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. Outside of Western Europe, it is sometimes referred to as neocommunism.[217] Some communist parties with strong popular support, notably the Italian Communist Party and the Communist Party of Spain, enthusiastically adopted Eurocommunism and the Communist Party of Finland was dominated by Eurocommunists.[218]

In the late 1970s and in the 1980s, the Socialist International had extensive contacts and held discussion with the two powers of the Cold War, the United States and the Soviet Union, regarding the relations between the East and West, along with arms control. Since then, the Socialist International has admitted as member parties the Nicaraguan Sandinista National Liberation Front and the left-wing Puerto Rican Independence Party as well as former communist parties such as the Italian Democratic Party of the Left and the Front for the Liberation of Mozambique. The Socialist International aided social democratic parties in re-establishing themselves after right-wing dictatorships were toppled in Portugal and Spain, respectively in 1974 and 1975. Until its 1976 congress in Geneva, the Socialist International had few members outside Europe and no formal involvement with Latin America.[219]

In Greece, the Panhellenic Socialist Movement, better known as PASOK, was founded on 3 September 1974 by Andreas Papandreou as a democratic socialist, left-wing nationalist, Venizelist and social democratic[220][221][222] party following the collapse of the military dictatorship of 1967–1974.[223] As a result of the 1981 legislative election, PASOK became Greece's first centre-left party to win a majority in the Hellenic Parliament and the party would later pass several important economic and social reforms that would reshape Greece in the years ahead.. In the United States, the Democratic Socialists of America was founded in 1983. The democratic socialist Michael Harrington and the socialist-feminist author Barbara Ehrenreich were elected as the first co-chairs of the organisation. The organisation does not stand its own candidates in elections and instead "fights for reforms [...] that will weaken the power of corporations and increase the power of working people".[57]

During the 1980s, Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev intended to move the Soviet Union towards of Nordic-style social democracy, calling it a "socialist beacon for all mankind".[224][225] Prior to its dissolution in 1991, the Soviet Union had the second largest economy in the world after the United States.[226] After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the economic integration of the Soviet republics was dissolved and industrial activity suffered a substantial decline.[227] The lasting legacy of the Soviet Union remains physical infrastructure created during decades of policies geared towards the construction of heavy industry and widespread environmental destruction.[228] The rapid transition to neoliberal capitalism and privatisation in the former Soviet Union and Eastern Bloc was accompanied by a steep fall in standards of living as poverty, unemployment, income inequality and excess mortality rose sharply, which was accompanied by the entrenchment of a newly established business oligarchy in the former countries of the Soviet Union.[229][230][231][232][233] The average post-communist country returned to 1989 levels of per-capita GDP only by 2005.[234]

Many social democratic parties, particularly after the Cold War, adopted neoliberal economic policies, including austerity, deregulation, financialisation, free trade and privatisation. They abandoned their pursuit of moderate socialism in favour of economic liberalism. In the United Kingdom, prominent democratic socialists within the Labour Party such as Michael Foot and Tony Benn put forward democratic socialism into an actionable manifesto during the 1970s and 1980s, but this was voted overwhelmingly against in the 1983 general election after Margaret Thatcher's victory in the Falklands War and the Labour Party's manifesto was referred to as "the longest suicide note in history" ever since.[235] As a result, Labour Party leader Neil Kinnock made a public attack against the entryist group Militant at the 1985 Labour Party conference in Bournemouth. The Labour Party ruled that Militant was ineligible for affiliation with the Labour Party and the party gradually expelled Militant supporters. The Kinnock leadership had refused to support the 1984–1985 miner's strike over pit closures, a decision that the party's left-wing and the National Union of Mine workers blamed for the strike's eventual defeat. In 1989, it adopted a new Declaration of Principles at the 18th Congress of the Socialist International in Stockholm, Sweden, saying: "Democratic socialism is an international movement for freedom, social justice, and solidarity. Its goal is to achieve a peaceful world where these basic values can be enhanced and where each individual can live a meaningful life with the full development of his or her personality and talents, and with the guarantee of human and civil rights in a democratic framework of society".[236]