Alcohol (drug): Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

Copyedit (major) |

||

| Line 4: | Line 4: | ||

[[File:Alcohol by Country.png|thumb|right|2004 data of [[List of countries by alcohol consumption|alcohol consumption per capita]] (age 15 or older), per year, by country, in liters of pure alcohol.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.who.int/entity/substance_abuse/publications/global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf |format=PDF |year=2004 |title=Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004 |deadurl=no |accessdate=2013-04-02}}</ref>]] |

[[File:Alcohol by Country.png|thumb|right|2004 data of [[List of countries by alcohol consumption|alcohol consumption per capita]] (age 15 or older), per year, by country, in liters of pure alcohol.<ref>{{cite web |url=http://www.who.int/entity/substance_abuse/publications/global_status_report_2004_overview.pdf |format=PDF |year=2004 |title=Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004 |deadurl=no |accessdate=2013-04-02}}</ref>]] |

||

Colloquially known as '''alcohol''', '''beverage alcohol''', or '''drinking alcohol''', is a general name for the [[#Alcohol family in alcoholic beverages|family of alcohols]] in [[alcoholic beverages]], a group of [[psychoactive drug]]s primary referring to [[ethyl alcohol]] (ethanol) |

Colloquially known as '''alcohol''', '''beverage alcohol''', or '''drinking alcohol''', is a general name for the [[#Alcohol family in alcoholic beverages|family of alcohols]] in [[alcoholic beverages]], a group of [[psychoactive drug]]s primary referring to [[ethyl alcohol]] (ethanol)<ref>{{cite web|author=USA |url=https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC2947861/ |title=Disparity between tonic and phasic ethanol-induced dopamine increases in the nucleus accumbens of rats |publisher=Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |date=2013-03-25 |accessdate=2013-09-17}}</ref><ref>Drugs and society - Page 189, Glen (Glen R.) Hanson, Peter J. Venturelli, Annette E. Fleckenstein - 2006</ref> '''Alcohol''' is one of the most commonly abused drugs in the world (Meropol, 1996)<ref>http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1010220-overview</ref> known to cause [[physical dependence]] and part of the [[drinking culture]]. |

||

Recently [[designer drugs]] like [[2M2B]], found extremely small quantities in beer and 20 times more potent than ethanol, have been sold outside the [[alcohol monopoly]] which means that it does not have any [[alcohol tax]]. |

|||

==Alcohol family in alcoholic beverages== |

==Alcohol family in alcoholic beverages== |

||

Revision as of 00:46, 20 June 2014

Colloquially known as alcohol, beverage alcohol, or drinking alcohol, is a general name for the family of alcohols in alcoholic beverages, a group of psychoactive drugs primary referring to ethyl alcohol (ethanol)[2][3] Alcohol is one of the most commonly abused drugs in the world (Meropol, 1996)[4] known to cause physical dependence and part of the drinking culture.

Recently designer drugs like 2M2B, found extremely small quantities in beer and 20 times more potent than ethanol, have been sold outside the alcohol monopoly which means that it does not have any alcohol tax.

Alcohol family in alcoholic beverages

In nature all alcohols act as psychoactive drugs which vary in potency and effects. Excessive concentrations of some alcohols (other than ethanol) may cause off-flavors, sometimes described as "spicy", "hot", or "solvent-like".

Some beverages, such as rum, whisky (especially Bourbon), incompletely rectified vodka (e.g. Siwucha), and traditional ales and ciders, are expected to have relatively high concentrations of non-hazardous aroma alcohols as part of their flavor profile;[8] European legislation demands minimum content of higher alcohols in certain distilled beverages (spirits) to give them their expected distinct flavour.[9] However, in other beverages, such as Korn, vodka, and lagers, the presence of other alcohols than ethanol is considered fusel alcohols.[8]

| Chemical alcohol classification | Simple or higher (consumable) alcohol | IUPAC nomenclature | Common name | Alcohol by volume (ABV)[8] | % intoxication by alcoholic beverage (Typical alcohol content / Typical alcohol content x Content of tot. alcohol x Potency compared to EtOH) | Color/Form[10] | Odor[10] | Taste[10] | Moderate intoxicating loading dose | BAC poisoning | LD50 in rat, oral[11] | Therapeutic index (Potency compared to EtOH/EtOH LD50:LD50 ratio) | Potency compared to EtOH | EtOH LD50:LD50 ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary | Simple | 2-phenylethanol | Phenethyl alcohol | 0.1% in non-yeasted cider (Kieser 1964): 100 mg/100 mL | ? | ? | Intense odour of roses | Burning | ? | ? | 1790 mg/kg | ? | ? | ? |

| Primary | Simple | Ethanol | EtOH | Up to 95.6% in rectified spirit | - | Clear, colorless, very mobile liquid | Mild, rather pleasant; like wine or whiskey. Weak, ethereal, vinous odor. | Burning | 20-50 mL/40% | 0.4% | 7060 mg/kg | - | - | - |

| Primary | Simple | Propan-1-ol | Propanol | 2.8% (mean) in Jamaican rum: 2384–3130 mg/100 mL. Up to 3500 mg/L (0.35%) in spirits.[12] | 8.4% (40/40×0.028×3) | Colorless liquid | Similar to ethanol | Characteristic ripe, fruity flavor. Burning taste | ? | ? | 1870 mg/kg | 0.8 (mean): 0.5-1.1 | 3 (mean): 2-4 | 3.8 |

| Primary | Simple | Tryptophol | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? | ? |

| Primary | Higher | 2-Methyl-1-propanol | 2M1P | 0.9% (mean) in Rye mash cistern room: 534–1197 mg/100 mL | ? | Colorless, oily liquid. Clear, colorless, refractive, mobile liquid. | Suffocating odor of fusel oil. Slightly suffocating; nonresidual alcoholic. Sweet, musty odor | Sweet whiskey taste | ? | ? | 2460 mg/kg | ? | ? | ? |

| Primary | Higher | 3-methyl-1-butanol | 3M1B | 1.5% (mean) in French Brandy: 859–2108 mg/100 mL | ? | Oily, clear liquid. Colorless liquid. | Characteristic, disagreeable odor. | Pungent, repulsive taste | ? | ? | 1300 mg/kg | ? | ? | 5.4 |

| Secondary | Higher | 2-Methyl-1-butanol | 2M1B | 1.2% (mean) in Bourbon: 910–1390 mg/100 mL | ? | Oily, clear liquid. Colorless liquid | Characteristic, disagreeable odor. | Pungent, repulsive taste | ? | ? | 4170 mg/kg[13] | ? | ? | 1.7 |

| Tertiary | Higher | 2-Methyl-2-butanol | 2M2B | 0.07% in beer: 70 mg/100 mL (see tert-Pentyl alcohol in ref) Found in cassava fermented beverages | 0.14% (5/5×0.0007×20) | Colorless liquid | Characteristic odor. Camphor odor | Burning taste | 2.0-4.0 gram | ? | 1000 mg/kg | 2.8 | 20 | 7.1 |

| Tertiary | Higher | 2-Methylpropan-2-ol | 2M2P | Identified, not quantified, in beer[14] | ? | Colorless liquid or solid (crystals) (above 78 degrees F) | Camphor-like odor | ? | ? | ? | 2743 mg/kg | ? | ? | 2.6 |

Ethanol

Ethanol is the principal psychoactive constituent in alcoholic beverages. With depressant effects on the central nervous system, it has a complex mode of action and affects multiple systems in the brain, most notably increasing the activity of GABA receptors.[15] Through positive allosteric modulation, it enhances the activity of naturally produced GABA. Other psychoactives such as benzodiazepines, barbiturates exert their effects by binding to the same receptor complex, thus have similar CNS depressant effects.[16]

Alcoholic beverages vary considerably in ethanol content and in foodstuffs they are produced from. Most alcoholic beverages can be broadly classified as fermented beverages, beverages made by the action of yeast on sugary foodstuffs, or distilled beverages, beverages whose preparation involves concentrating the ethanol in fermented beverages by distillation. The ethanol content of a beverage is usually measured in terms of the volume fraction of ethanol in the beverage, expressed either as a percentage or in alcoholic proof units.

Fermented beverages can be broadly classified by the foodstuff they are fermented from. Beers are made from cereal grains or other starchy materials, wines and ciders from fruit juices, and meads from honey. Cultures around the world have made fermented beverages from numerous other foodstuffs, and local and national classifications for various fermented beverages abound.

Distilled beverages are made by distilling fermented beverages. Broad categories of distilled beverages include whiskeys, distilled from fermented cereal grains; brandies, distilled from fermented fruit juices; and rum, distilled from fermented molasses or sugarcane juice. Vodka and similar neutral grain spirits can be distilled from any fermented material (grain and potatoes are most common); these spirits are so thoroughly distilled that no tastes from the particular starting material remain. Numerous other spirits and liqueurs are prepared by infusing flavors from fruits, herbs, and spices into distilled spirits. A traditional example is gin, which is created by infusing juniper berries into a neutral grain alcohol.

The ethanol content in alcoholic beverages can be increased by means other than distillation. Applejack is traditionally made by freeze distillation, by which water is frozen out of fermented apple cider, leaving a more ethanol-rich liquid behind. Ice beer (also known by the German term Eisbier or Eisbock) is also freeze-distilled, with beer as the base beverage. Fortified wines are prepared by adding brandy or some other distilled spirit to partially fermented wine. This kills the yeast and conserves a portion of the sugar in grape juice; such beverages are not only more ethanol-rich but are often sweeter than other wines.

Alcoholic beverages are used in cooking for their flavors and because alcohol dissolves hydrophobic flavor compounds.

Just as industrial ethanol is used as feedstock for the production of industrial acetic acid, alcoholic beverages are made into vinegar. Wine and cider vinegar are both named for their respective source alcohols, whereas malt vinegar is derived from beer.

Human consumption

Recreational

Since ancient times, people around the world have been drinking alcoholic beverages. Reasons for drinking alcoholic beverages vary and include:

- Recreational purposes: Anxiolytic, and euphoric effects

- Artistic inspiration

- Putative aphrodisiac effects

- Medical purposes

In countries that have a drinking culture, social stigma may cause many people not to view alcohol as a drug because it is an important part of social events. In these countries, many young binge drinkers prefer to call themselves hedonists rather than binge drinkers[17] or recreational drug users. Undergraduate students often position themselves outside the categories of "serious" or "anti-social" drinkers.[18] However, about 40 percent of college students in the United States[19] could be considered alcoholics according to new criteria in Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders 5 but most college binge drinkers and drug users don't develop lifelong problems.[20][21]

Controversial entheogen

Some religions forbid, discourage, or restrict the drinking of alcohol for various reasons. These include Islam, Jainism, Sikhism, the Bahá'í Faith, the Church of God In Christ, The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, the Seventh-day Adventist Church, the Church of Christ, Scientist, the United Pentecostal Church International, Theravada, most Mahayana schools of Buddhism, some Protestant denominations of Christianity, some sects of Taoism (Five Precepts (Taoism) and Ten Precepts (Taoism)), and some sects of Hinduism. In some regions with a dominant religion the production, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages is forbidden to everybody, regardless of religion. For instance, some Islamic states, including member states of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation, such as Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Brunei, Iran, Kuwait, Libya, Saudi Arabia, Sudan, and Yemen, prohibit alcohol because they are forbidden by Islam.[22]

In some religions alcoholic beverages are used for ritual purposes. For example, the Roman Catholic Church uses wine in the celebration of the Eucharist; in Judaism kosher wine is used in holidays and rituals.

Carnival in the Netherlands is historically a Roman Catholic feast which is well known for its excessive drinking of alcohol.

Poly drug products

Caffeinated alcohol

Caffeinated alcoholic drinks combine alcohol, caffeine, and the ingredients of energy drinks into one drink. In 2010 and 2011, this type of beverage faced criticism for posing health risks to their drinkers. Alcohol and caffeine are both psychoactive drugs, drugs that are mixed are referred to as poly drug use. As a response FDA have introduced a caffeinated alcohol drinks ban.

However, to date a few ready to drink product exist including 3 A.M. Vodka.

Pharmaceutical

Ethanol as methanol antidote

Ethanol is sometimes used to treat poisoning by other, more toxic alcohols, in particular methanol[23] and ethylene glycol. Ethanol competes with other alcohols for the alcohol dehydrogenase enzyme, lessening metabolism into toxic aldehyde and carboxylic acid derivatives,[24] and reducing one of the more serious toxic effect of the glycols to crystallize in the kidneys.

Pharmacology

Ethanol binds to α7-nAChRs as an agonist, GABA receptor (especially the δ subunit) as a positive allosteric modulator, 5-HT3 receptor agonist, NMDA receptor antagonist, AMPA receptor antagonist, Kainate receptor antagonist, glycine receptor agonist and an inhibitor of potassium, sodium and calcium ion channels. It also appears to cause an increase in dopamine through a poorly understood process that may involve inhibiting the enzyme that breaks dopamine down.[25] Ethanol also appears to block the reuptake of adenosine.[26]

The removal of ethanol through oxidation by alcohol dehydrogenase in the liver from the human body is limited. Hence, the removal of a large concentration of alcohol from blood may follow zero-order kinetics. This means that alcohol leaves the body at a constant rate, rather than having an elimination half-life.[27]

Also, the rate-limiting steps for one substance may be in common with other substances. For instance, the blood alcohol concentration can be used to modify the biochemistry of methanol and ethylene glycol. Methanol itself is not highly toxic, but its metabolites formaldehyde and formic acid are; therefore, to reduce the concentration of these harmful metabolites, ethanol can be ingested to reduce the rate of methanol metabolism due to shared rate-limiting steps.[citation needed] Ethylene glycol poisoning can be treated in the same way.

Pure ethanol will irritate the skin and eyes.[28] Nausea, vomiting and intoxication are symptoms of ingestion. Long-term use by ingestion can result in serious liver damage.[29] Atmospheric concentrations above one in a thousand are above the European Union Occupational exposure limits.[29]

Short-term

| BAC (g/L) | BAC (% v/v) |

Symptoms[30] |

|---|---|---|

| 0.5 | 0.05% | Euphoria, talkativeness, relaxation |

| 1 | 0.1 % | Central nervous system depression, nausea, possible vomiting, impaired motor and sensory function, impaired cognition |

| >1.4 | >0.14% | Decreased blood flow to brain |

| 3 | 0.3% | Stupefaction, possible unconsciousness |

| 4 | 0.4% | Possible death |

| >5.5 | >0.55% | Death |

Effects on the central nervous system

Ethanol is a central nervous system depressant and has significant psychoactive effects in sublethal doses; for specifics, see "Effects of alcohol on the body by dose". Based on its abilities to change the human consciousness, ethanol is considered a psychoactive drug.[31] Death from ethanol consumption is possible when blood alcohol level reaches 0.4%. A blood level of 0.5% or more is commonly fatal. Levels of even less than 0.1% can cause intoxication, with unconsciousness often occurring at 0.3–0.4%.[32]

The amount of ethanol in the body is typically quantified by blood alcohol content (BAC), which is here taken as weight of ethanol per unit volume of blood. The table at the right summarizes the symptoms of ethanol consumption. Small doses of ethanol, in general, produce euphoria and relaxation; people experiencing these symptoms tend to become talkative and less inhibited, and may exhibit poor judgment. At higher dosages (BAC > 1 g/L), ethanol acts as a central nervous system depressant, producing at progressively higher dosages, impaired sensory and motor function, slowed cognition, stupefaction, unconsciousness, and possible death.

Ethanol acts in the central nervous system by binding to the GABA-A receptor, increasing the effects of the inhibitory neurotransmitter GABA (i.e., it is a positive allosteric modulator).[33]

Prolonged heavy consumption of alcohol can cause significant permanent damage to the brain and other organs. See Alcohol consumption and health.

According to the US National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, in 2002 about "41% of people fatally injured in traffic crashes were in alcohol related crashes".[34] The risk of a fatal car accident increases exponentially with the level of alcohol in the driver's blood.[35] Most drunk driving laws governing the acceptable levels in the blood while driving or operating heavy machinery set typical upper limits of blood alcohol content (BAC) between 0.02% and 0.08%.[citation needed]

Discontinuing consumption of alcohol after several years of heavy drinking can also be fatal. Alcohol withdrawal can cause anxiety, autonomic dysfunction, seizures, and hallucinations. Delirium tremens is a condition that requires people with a long history of heavy drinking to undertake an alcohol detoxification regimen.

The reinforcing effects of alcohol consumption are also mediated by acetaldehyde generated by catalase and other oxidizing enzymes such as cytochrome P-4502E1 in the brain.[36] Although acetaldehyde has been associated with some of the adverse and toxic effects of ethanol, it appears to play a central role in the activation of the mesolimbic dopamine system.[37]

Effects on metabolism

Ethanol within the human body is converted into acetaldehyde by alcohol dehydrogenase and then into the acetyl in acetyl CoA by acetaldehyde dehydrogenase. Acetyl CoA is the final product of both carbohydrate and fat metabolism, where the acetyl can be further used to produce energy or for biosynthesis. As such, ethanol is a nutrient. However, the product of the first step of this breakdown, acetaldehyde,[38] is more toxic than ethanol. Acetaldehyde is linked to most of the clinical effects of alcohol. It has been shown to increase the risk of developing cirrhosis of the liver[16] and multiple forms of cancer.

During the metabolism of alcohol via the respective dehydrogenases, NAD (Nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide) is converted into reduced NAD. Normally, NAD is used to metabolise fats in the liver, and as such alcohol competes with these fats for the use of NAD. Prolonged exposure to alcohol means that fats accumulate in the liver, leading to the term 'fatty liver'. Continued consumption (such as in alcoholism) then leads to cell death in the hepatocytes as the fat stores reduce the function of the cell to the point of death. These cells are then replaced with scar tissue, leading to the condition called cirrhosis.

Drug interactions

Ethanol can intensify the sedation caused by other central nervous system depressant drugs such as barbiturates, benzodiazepines, opioids, non-benzodiazepines (such as Zolpidem and Zopiclone), antipsychotics, sedative antihistamines, and antidepressants.[32] It interacts with cocaine in vivo to produce cocaethylene, another psychoactive substance.[39]

Alcohol and metronidazole

One of the most important drug/food interaction that should be noted is between alcohol and metronidazole.

Metronidazole is an antibacterial agent that kills bacteria by damaging cellular DNA and hence cellular function.[40] Metronidazole is usually given to people who have diarrhea caused by Clostridium difficile bacteria. C. difficile is one of the most common microorganisms that cause diarrhea and can lead to complications such as colon inflammation and even more severely, death.

Patients who are taking metronidazole are strongly advised to avoid alcohol, even after 1 hour after the last dose. The reason is that alcohol and metronidazole can lead to side effects such as flushing, headache, nausea, vomiting, abdominal cramps, and sweating.[41][42][42] These symptoms are often called the disulfiram-like reaction. The proposed mechanism of action for this interaction is that metronidazole can bind to an enzyme that normally metabolizes alcohol. Binding to this enzyme may impair the liver's ability to process alcohol for proper excretion.[43]

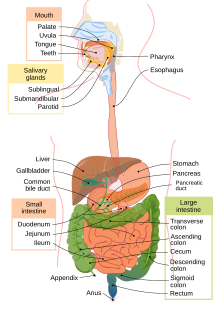

Alcohol and digestion

A part of ethyl alcohol is hydrophobic. This hydrophobic or lipophilic end can diffuse across cells that line the stomach wall. In fact, alcohol is one of the rare substances that can be absorbed in the stomach. Most food substances are absorbed in the small intestine. However, even though alcohol can be absorbed in the stomach, it is mostly absorbed in the small intestine because the small intestine has a large surface area that promotes absorption. Once alcohol is absorbed in the small intestine, it delays the release of stomach contents from emptying into the small intestine. Thus, alcohol can delay the rate of absorption of nutrients.[44] After absorption, alcohol reaches the liver where it is metabolized.

How Breathalyzers work:

Alcohol that is not processed by the liver goes to the heart. The liver can process only a certain amount of alcohol per unit time. Thus, when a person drinks too much alcohol, more alcohol can reach the heart. In the heart, alcohol reduces the force of heart contractions. Consequently, the heart will pump less blood, lowering overall body blood pressure.[45] Also, blood that reaches the heart goes to the lungs to replenish blood's oxygen concentration. It is at this stage that a person can breathe out traces of alcohol.[45] This is the underlying principle of the alcohol breath testing (or breathalyzers) to determine if a driver has been drinking and driving.[46]

From the lungs, blood returns to the heart and will be distributed throughout the body. Interestingly, alcohol increases levels of high-density lipoproteins(HDLs), which carry cholesterol.[45] Alcohol is known to make blood less likely to clot, reducing risk of heart attack and stroke. This could be the reason why alcohol could produce health benefits when consumed in moderate amounts.[47] Also, alcohol dilates blood vessels. Consequently, a person will feel warmer, and their face turns flush and pink.[45]

Why people lose their sense of balance after drinking alcohol:

When alcohol reaches the brain, it has the ability to delay signals that are sent between nerve cells that control balance, thinking and movement.[45]

Why people frequently urinate after drinking alcohol:

Moreover, alcohol can affect the brain's ability to produce antidiuretic hormones. These hormones are responsible for controlling the amount of urine that is produced. Alcohol prevents the body from reabsorbing water, and consequently a person who recently drank alcohol will urinate frequently.[45]

Alcohol and gastrointestinal diseases

Alcohol stimulates gastric juice production, even when food is not present. In other words, when a person drinks alcohol, the alcohol will stimulate stomach's acidic secretions that are intended to digest protein molecules. Consequently, the acidity has potential to harm the inner lining of the stomach. Normally, the stomach lining is protected by a mucus layer that prevents any acids from reaching the stomach cells.

However, in patients who have a peptic ulcer disease (PUD), this mucus layer is broken down. PUD is commonly associated with a bacteria H. pylori. H. pylori secretes a toxin that weakens the mucosal wall. As a result, acid and protein enzymes penetrate the weakened barrier. Because alcohol stimulates a person's stomach to secrete acid, a person with PUD should avoid drinking alcohol on an empty stomach. Drinking alcohol would cause more acid release to damage the weakened stomach wall.[48] Complications of this disease could include a burning pain in the abdomen, bloating and in severe cases, the presence of dark black stools indicate internal bleeding.[49] A person who drinks alcohol regularly is strongly advised to reduce their intake to prevent PUD aggravation.[49]

Magnitude of effects

Some individuals have less effective forms of one or both of the metabolizing enzymes, and can experience more severe symptoms from ethanol consumption than others. However, those having acquired alcohol tolerance have a greater quantity of these enzymes, and metabolize ethanol more rapidly.[50]

Long-term

Birth defects

Ethanol is classified as a teratogen. See fetal alcohol syndrome and fetal alcohol spectrum disorder.

Cancer

IARC list ethanol in alcoholic beverages as Group 1 carcinogens and arguments "There is sufficient evidence for the carcinogenicity of acetaldehyde (the major metabolite of ethanol) in experimental animals.".[51]

Other effects

Frequent drinking of alcoholic beverages has been shown to be a major contributing factor in cases of elevated blood levels of triglycerides.[52]

Ethanol is also widely used, clinically and over the counter, as an antitussive agent.[53]

Tragedies involving alcohols

Ethanol

In 2005 a mother infanticided her month-old baby with a microwave oven by cooking her for 2 minutes. China Arnold claimed to be under the influence of alcohol and Galbraith testified that Arnold told him during his initial questioning: "If I hadn't gotten so drunk, I guess my baby wouldn't have died.".[54][55] On May 20, 2011, Arnold was sentenced to life imprisonment without parole. Her attorney says they will appeal the decision.[56]

In November 2011, Rehtaeh Parsons, then 15, allegedly went with a friend to a home in which she was reportedly gang raped by 4 teenage boys.[57] The teenagers were drinking vodka at a small party. Parsons had little memory of the event, except that at one point she vomited. While a boy was allegedly raping her, the incident was photographed and the photo became widespread in Parsons' school and town in three days. Afterwards, many in school called Parsons a "slut" and she received texts and Facebook messages from people requesting to have sex with her. The alleged rape went unreported for several days until Parsons broke down and told her family, who contacted an emergency health team and the police.[58] Later the Cole Harbour District High School student, Parsons, attempted suicide by hanging[59] on April 4, 2013, at her home in Dartmouth, Nova Scotia, Canada, leading to a coma and the decision to switch her life support machine off on April 7, 2013.[60]

Methanol outbreaks

Outbreaks of methanol poisoning have occurred when methanol is used to adulterate moonshine (bootleg liquor).[61]

Methanol has a high toxicity in humans. If as little as 10 mL of pure methanol is ingested, for example, it can break down into formic acid, which can cause permanent blindness by destruction of the optic nerve, and 30 mL is potentially fatal,[62] although the median lethal dose is typically 100 mL (3.4 fl oz) (i.e. 1–2 mL/kg body weight of pure methanol[63]). Reference dose for methanol is 0.5 mg/kg/day.[64] Toxic effects take hours to start, and effective antidotes can often prevent permanent damage.[62] Because of its similarities in both appearance and odor to ethanol (the alcohol in beverages), it is difficult to differentiate between the two.

Historical uses

Before the development of modern medicines, ethanol was used for a variety of medical purposes. It has been known to be used as a truth drug (as hinted at by the maxim "in vino veritas"), as medicine for depression and as an anesthetic.[citation needed]

Ethanol was commonly used as fuel in early bipropellant rocket (liquid propelled) vehicles, in conjunction with an oxidizer such as liquid oxygen. The German V-2 rocket of World War II, credited with beginning the space age, used ethanol, mixed with 25% of water to reduce the combustion chamber temperature.[65][66] The V-2's design team helped develop U.S. rockets following World War II, including the ethanol-fueled Redstone rocket which launched the first U.S. satellite.[67] Alcohols fell into general disuse as more efficient rocket fuels were developed.[66]

Legal status

Alcohol laws regulate the manufacture, sale, and consumption of alcoholic beverages. Such laws often seek to reduce the availability of these beverages for the purpose of reducing the health and social effects of their consumption.

In particular, such laws specify the legal drinking age which usually varies between 16 and 25 years, sometimes depending on the type of drink. Some countries do not have a legal drinking or purchasing age, but most set the age at 18 years.[68] This can also take the form of distribution only in licensed stores or in monopoly stores. Often, this is combined with some form of taxation. In some jurisdictions alcoholic beverages have been totally prohibited for reasons of religion (e.g., Islamic countries with certain interpretations of sharia law) or perceived public morals and health (e.g., Prohibition in the United States from 1920 to 1933).

References

- ^ "Global Status Report on Alcohol 2004" (PDF). 2004. Retrieved 2013-04-02.

{{cite web}}: Unknown parameter|deadurl=ignored (|url-status=suggested) (help) - ^ USA (2013-03-25). "Disparity between tonic and phasic ethanol-induced dopamine increases in the nucleus accumbens of rats". Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-09-17.

- ^ Drugs and society - Page 189, Glen (Glen R.) Hanson, Peter J. Venturelli, Annette E. Fleckenstein - 2006

- ^ http://emedicine.medscape.com/article/1010220-overview

- ^ Hans Brandenberger & Robert A. A. Maes, ed. (1997). Analytical Toxicology for Clinical, Forensic and Pharmaceutical Chemists. p. 401. ISBN 3-11-010731-7.

- ^ D. W. Yandell; et al. (1888). "Amylene hydrate, a new hypnotic". The American Practitioner and News. 5. Lousville KY: John P. Morton & Co: 88–89.

{{cite journal}}: Explicit use of et al. in:|author=(help) - ^ Carey, Francis. Organic Chemistry (4 ed.). ISBN 0072905018. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ a b c Aroma of Beer, Wine and Distilled Alcoholic Beverages

- ^ https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/18295386

- ^ a b c Pubchem Compound, https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/

- ^ "ChemIDplus Advanced". Chem.sis.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ "Propanol, 1- (EHC 102, 1990)". Inchem.org. 1989-04-14. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ "2-Methyl-1-Butanol". Grrexports.com. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ "t-butyl alcohol". Toxnet.nlm.nih.gov. Retrieved 2013-02-05.

- ^ Chastain G (2006). "Alcohol, neurotransmitter systems, and behavior". The Journal of general psychology. 133 (4): 329–35. doi:10.3200/GENP.133.4.329-335. PMID 17128954.

- ^ a b Boggan, Bill. "Effects of Ethyl Alcohol on Organ Function". Chemases.com. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17981452, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17981452instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 17675648, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=17675648instead. - ^ Time: DSM-5 Could Categorize 40% of College Students as Alcoholics, 14 May 2012 The article reports that the new DSM-5 criteria could increase the number of people diagnosed as alcoholics by 60%

- ^ Szalavitz, Maia (2012-05-14). "DSM-5 Could Categorize 40% of College Students as Alcoholics | TIME.com". Healthland.time.com. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ Sanderson, Megan (2012-05-22). "About 37 percent of college students could now be considered alcoholics | Emerald Media". Dailyemerald.com. Retrieved 2013-10-14.

- ^ "Saudi Arabia". Travel.state.gov. Retrieved 2012-10-22.

- ^ "Methanol Poisoning". Cambridge University School of Clinical Medicine. Archived from the original on 2006-01-07. Retrieved 2007-09-04.[dead link]

- ^ Barceloux DG, Bond GR, Krenzelok EP, Cooper H, Vale JA (2002). "American Academy of Clinical Toxicology practice guidelines on the treatment of methanol poisoning". J. Toxicol. Clin. Toxicol. 40 (4): 415–46. doi:10.1081/CLT-120006745. PMID 12216995.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "The Brain from Top to Bottom – Alcohol (Intermediate, Molecular)". Canadian Institute of Neurosciences, Mental Health and Addiction. McGill University. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

- ^ White, BD (May 1994). "Type II corticosteroid receptor stimulation increases NPY gene expression in basomedial hypothalamus of rats". The American journal of physiology. 266 (5 Pt 2): R1523-9. PMID 8203629.

{{cite journal}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Becker, CE (2013-08-12). "The Clinical Pharmacology of Alcohol". California Medicine. 113 (3). Ncbi.nlm.nih.gov: 37–45. PMC 1501558. PMID 5457514.

- ^ Minutes of Meeting. Technical Committee on Classification and Properties of Hazardous Chemical Data (January 12–13, 2010).

- ^ a b "Safety data for ethyl alcohol". Msds.chem.ox.ac.uk. 2008-05-09. Retrieved 2011-01-03.

- ^ Pohorecky LA, Brick J (1988). "Pharmacology of ethanol". Pharmacol. Ther. 36 (2–3): 335–427. doi:10.1016/0163-7258(88)90109-X. PMID 3279433.

- ^ Alcohol use and safe drinking. US National Institutes of Health .

- ^ a b Yost, David A. (2002). "Acute care for alcohol intoxication" (PDF). 112 (6). Postgraduate Medicine Online. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2010-12-14. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Santhakumar V, Wallner M, Otis TS (2007). "Ethanol acts directly on extrasynaptic subtypes of GABAA receptors to increase tonic inhibition". Alcohol. 41 (3): 211–21. doi:10.1016/j.alcohol.2007.04.011. PMC 2040048. PMID 17591544.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Hingson R, Winter M (2003). "Epidemiology and consequences of drinking and driving". Alcohol research & health : the journal of the National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism. 27 (1): 63–78. PMID 15301401.

- ^ Naranjo CA, Bremner KE (1993). "Behavioural correlates of alcohol intoxication". Addiction. 88 (1): 25–35. doi:10.1111/j.1360-0443.1993.tb02761.x. PMID 8448514.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 21332529, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=21332529instead. - ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 18001279, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=18001279instead. - ^ Boggan, Bill. "Metabolism of Ethyl Alcohol in the Body". Chemases.com. Retrieved 2007-09-29.

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 12485948, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=12485948instead. - ^ Repchinsky C (ed.) (2012). Compendium of pharmaceuticals and specialties, Ottawa: Canadian Pharmacists Association.[full citation needed]

- ^ Attention: This template ({{cite pmid}}) is deprecated. To cite the publication identified by PMID 2952478, please use {{cite journal}} with

|pmid=2952478instead. - ^ a b SCS Pharmaceuticals. Flagyl® IV and Flagyl® I.V. RTU® (metronidazole hydrochloride) prescribing information (dated April 16, 1997). In: Physicians’ desk reference. 48th ed. Montvale, NJ: Medical Economics Company Inc; 1998:2563-5.

- ^ "Ethanol/metronidazole", p. 335 in Tatro DS, Olin BR, eds. Drug interaction facts. St. Louis: JB Lippincott Co, 1988, ISBN 0932686478.

- ^ Sherwood, Lauralee; Kell, Robert and Ward, Christopher (2010). Human Physiology: From Cells to Systems. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0-495-39184-5.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)[page needed] - ^ a b c d e f How Your Body Processes Alcohol. Dummies.com. Retrieved on 2013-04-27.[unreliable source?]

- ^ How Breathalyzers work. Electronics.howstuffworks.com

- ^ "Alcohol effects on the digestive system". Alcoholrehab.com

- ^ Overview of Peptic Ulcer Disease: Etiology and Pathophysiology. Medscape.com. Retrieved on 2013-04-27.

- ^ a b Peptic Ulcer Disease (Stomach Ulcers) Cause, Symptoms, Treatments. Webmd.com. Retrieved on 2013-04-27.

- ^ Agarwal DP, Goedde HW (1992). "Pharmacogenetics of alcohol metabolism and alcoholism". Pharmacogenetics. 2 (2): 48–62. doi:10.1097/00008571-199204000-00002. PMID 1302043.

- ^ http://monographs.iarc.fr/ENG/Classification/ClassificationsGroupOrder.pdf

- ^ "Triglycerides". American Heart Association. Archived from the original on 2007-08-27. Retrieved 2007-09-04.

- ^ Calesnick, B.; Vernick, H. (1971). "Antitussive activity of ethanol". Q J Stud Alcohol. 32 (2): 434–441. PMID 4932255.

- ^ Hannah, James (20 July 2007). "Drunken mom microwaved one-month-old baby". Daily News. New York, NY, USA: Mortimer Zuckerman. The Associated Press. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "Life in prison for Ohio mom in microwave-baby case". Daily News. New York, NY, USA: Mortimer Zuckerman. The Associated Press. 8 July 2008. Retrieved 27 February 2012.

- ^ "Jury Recommends Life Without Parole for China Arnold" Dayton Daily News 20 May 2011

- ^ Ross, Selena. "Who failed Rehtaeh Parsons?". The Chronicle Herald. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Rape, bullying led to N.S. teen's death, says mom", CBC News, April 9, 2013, URL accessed April 13, 2013.

- ^ "Rehtaeh Parsons Video Tribute Marks Life Of 'Angel' (VIDEO)," The Huffington Post Canada, April 9, 2013, URL accessed April 14, 2013.

- ^ Jauregui, Andres (April 9, 2013). "Rehtaeh Parsons, Canadian Girl, Dies After Suicide Attempt; Parents Allege She Was Raped By 4 Boys". The Huffington Post. Retrieved 11 April 2013.

- ^ "Application to Include Fomepizole on the WHO Model List of Essential Medicines" (pdf). November 2012. p. 10.

- ^ a b Vale A (2007). "Methanol". Medicine. 35 (12): 633–4. doi:10.1016/j.mpmed.2007.09.014.

{{cite journal}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|month=(help) - ^ "Methanol Poisoning Overview". Antizol. Retrieved 4/10/11.

{{cite web}}: Check date values in:|accessdate=(help) dead link - ^ Methanol (CASRN 67-56-1)

- ^ Darling, David. "The Internet Encyclopedia of Science: V-2".

- ^ a b Braeunig, Robert A. "Rocket Propellants." (Website). Rocket & Space Technology, 2006. Retrieved on 2007-08-23.

- ^ "A Brief History of Rocketry." NASA Historical Archive, via science.ksc.nasa.gov.

- ^ "Minimum Age Limits Worldwide". International Center for Alcohol Policies. Retrieved 2009-09-20.

External links

- Emerald Media Group: About 37 percent of college students could now be considered alcoholics

- Alcohol, Health-EU Portal

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — Website

- International Center for Alcohol Policies — List of Tables

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism - What Is a Standard Drink?

- Most Widely Consumed Alcoholic Beverages