History of Jakarta: Difference between revisions

Rochelimit (talk | contribs) |

Rochelimit (talk | contribs) expanded, replace poor images |

||

| Line 123: | Line 123: | ||

==Japanese Occupation== |

==Japanese Occupation== |

||

[[image:COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Schets van de Japanse intocht in Batavia zoals de Japanners het zich voorstelden TMnr 10001766.jpg|thumbnail|right|Sketch of the Japanese entry into Batavia]] |

[[image:COLLECTIE TROPENMUSEUM Schets van de Japanse intocht in Batavia zoals de Japanners het zich voorstelden TMnr 10001766.jpg|thumbnail|right|Sketch of the Japanese entry into Batavia]] |

||

On March 5, 1942 Batavia fell to the Japanese troops. The Dutch formally surrendered to the Japanese occupation forces on March 9, 1942 and rule of the colony was transferred to Japan. The city was renamed '''Jakarta''', with official name '''Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi''' (Special Municipality of Jakarta). This period was a period of decline in Batavia. During three and a half years of occupation, both the economic situation and the physical conditions of Indonesian cities deteriorated. Many buildings were vandalized as metal was needed for the war, many iron statues from the Dutch colonial period were taken away by the Japanese troops.<ref name= |

On March 5, 1942 Batavia fell to the Japanese troops. The Dutch formally surrendered to the Japanese occupation forces on March 9, 1942 and rule of the colony was transferred to Japan. The city was renamed '''Jakarta''', with official name '''Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi''' (Special Municipality of Jakarta). This period was a period of decline in Batavia. During three and a half years of occupation, both the economic situation and the physical conditions of Indonesian cities deteriorated. Many buildings were vandalized as metal was needed for the war, many iron statues from the Dutch colonial period were taken away by the Japanese troops.<ref name=heritage6 /> |

||

To strengthen its position in Indonesia, the Japanese government issued an Act No. 42 1942 on the "Restoration of the Regional Administration System". This act divided Java into several ''Syuu'' (Resident Administration or ''Karesidenan''), each was led by a Bupati (Regent). Each Syuu was divided into several ''Shi'' (Municipality or ''Stad Gemeente''), led by a Wedana (District Head). Below a Wedana is a Wedana Assistant (Sub District Head), which in turn headed a Lurah (Village Unit Head), which in turn headed a Kepala Kampung (Kampung Chief). |

To strengthen its position in Indonesia, the Japanese government issued an Act No. 42 1942 on the "Restoration of the Regional Administration System". This act divided Java into several ''Syuu'' (Resident Administration or ''Karesidenan''), each was led by a Bupati (Regent). Each Syuu was divided into several ''Shi'' (Municipality or ''Stad Gemeente''), led by a Wedana (District Head). Below a Wedana is a Wedana Assistant (Sub District Head), which in turn headed a Lurah (Village Unit Head), which in turn headed a Kepala Kampung (Kampung Chief). |

||

| Line 145: | Line 145: | ||

{{see also|Indonesian National Revolution}} |

{{see also|Indonesian National Revolution}} |

||

==Early independence |

==Early independence era (1950s-1960s)== |

||

[[Image: |

[[Image:Merdeka Square Monas 02.jpg|thumb|right|Monas, or the national monument, symbolizing the fight for Indonesian independence.]] |

||

Following the surrender of the Japanese, Indonesia declared its independence in 1945, but urban development continued to stagnate whilst the Dutch tried to reestablish themselves. In 1947, the Dutch succeeded in implementing a set of planning regulations for urban development - the SSO/SVV (''Stadsvormings-ordonantie/Stadsvormings-verordening'') - which had been drawn up before the war. |

Following the surrender of the Japanese, Indonesia declared its independence in 1945, but urban development continued to stagnate whilst the Dutch tried to reestablish themselves. In 1947, the Dutch succeeded in implementing a set of planning regulations for urban development - the SSO/SVV (''Stadsvormings-ordonantie/Stadsvormings-verordening'') - which had been drawn up before the war. |

||

In 1950, the Dutch finally left and their residences and properties were taken over by the Indonesian government in 1957. Once independence was secured, Jakarta was once again made the national capital.<ref name="witton101"/> The departure of the Dutch caused a massive migration of the rural people into Jakarta in response to a perception that the city is the place for economic opportunities. The kampung areas swelled. |

In 1950, the Dutch finally left and their residences and properties were taken over by the Indonesian government in 1957. Once independence was secured, Jakarta was once again made the national capital.<ref name="witton101"/> The departure of the Dutch caused a massive migration of the rural people into Jakarta in response to a perception that the city is the place for economic opportunities. The kampung areas swelled. |

||

Indonesia's founding president, [[Sukarno]], envisaged Jakarta as a great international city instigating large, government-funded projects undertaken with openly nationalistic architecture that strived to show the newly independent nation's pride in itself.<ref>Schoppert, Peter ''et al.'' (1997). ''Java Style, '' p. _.</ref> |

Indonesia's founding president, [[Sukarno]], envisaged Jakarta as a great international city instigating large, government-funded projects undertaken with openly nationalistic architecture that strived to show the newly independent nation's pride in itself.<ref>Schoppert, Peter ''et al.'' (1997). ''Java Style, '' p. _.</ref> To promote nationalistic pride amongst Indonesian people, Sukarno interpreted his modernist ideas in his urban planning for the capital (eventually Jakarta). Many monumental projects of Sukarno are the clover-leaf highway, a broad by-pass in Jakarta ([[Jalan Jenderal Sudirman]]), four high-rise hotels including the [[Hotel Indonesia]], [[DPR/MPR Building|a new parliament building]], the [[Bung Karno Stadium]], [[Istiqlal Mosque|the largest mosque in Southeast Asia]], and numerous monuments and memorials including [[Monas|The National Monument]]. |

||

==Kampung improvement program (1970s)== |

|||

==Suharto era== |

|||

Since 1970, the national development policy has been focused primarily on economic growth and achievement. This situation encouraged the emergence of a large number of housing projects in the private sector. Government housing schemes have also been implemented to cope with the growth of urban populations. During this period, kampung improvement programmes have been reintroduced to improve conditions in existing areas. This Kampung Improvement Programme of Jakarta, enacted by [[Ali Sadikin]], the governor of Jakarta (1966 to 1977), was a success. The program had won the 1980 [[Aga_Khan_Award_for_Architecture#First_.281978-1980.29|Aga Khan Award for architecture in 1980]]. Ali Sadikin was also credited with rehabilitating public services, clearing out slum dwellers, banned rickshaws, and street peddlers.<ref name="witton101"/> Despite the huge success of this policy, they have been discontinued because they were considered to be too biased toward improving the physical infrastructure solely.<ref name=heritage6 /> |

|||

| ⚫ | |||

==Recent urban development (1980s - now)== |

|||

During the 1980s, smaller sites have been acquired for high-rise projects, while larger parcels of land have been subdivided for low-key projects such as the building of new shophouses. This period also saw the removal of kampongs from the inner city areas and the destruction of many historical buildings.<ref name=heritage6 /> One infamous case is the demolition of the Society of Harmonie to be turned into a parking. |

|||

The period between the late 1980s and the mid 1990s saw a massive increase in foreign investment as Jakarta became the focus of real estate boom. This enforcement of overseas capital into joing-venture property and construction projects with local developers brought many foreign architects to Indonesia. However, unlikt the Dutch architects of the 1930s, many of these expatriate architects were unfamiliar with the tropics, while their local partners had received a similar Modernist architectural training. As a result, downtown areas in Jakarta gradually came to resemble those of big cities in the West and often at a high environmental cost: massive high-rise buildings consume huge amounts of energy in terms of air-conditioning and other services.<ref name=heritage6 /> |

|||

| ⚫ | The period of Jakarta's economic boom ended abruptly in the [[East Asian Financial Crisis|1997 East Asian Economic crisis]]. Many projects were left abandoned. The city became the centre of violence, protest, and political maneuvering as long-time president [[Suharto]] began to lose his grip on power. Tensions reached a peak in May 1998 when [[Trisakti shootings|four students were shot dead]] at [[Trisakti University]] by security forces; four days of riots ensued resulting in an estimated 6,000 buildings damaged or destroyed, and the loss of 1,200 lives. The Chinese of the Glodok district were hardest hit and stories of rape and murder later emerged.<ref name="witton101"/> The following years Jakarta was the centre of popular protest and national political instability, including several terms of ineffective Presidents, and a number [[Jemaah Islamiah]]-connected bombings. Jakarta is now witnessing a period of political stability and prosperity along a boom in construction. |

||

==Notes and references== |

==Notes and references== |

||

Revision as of 08:45, 20 August 2011

The history of Jakarta begins with its first recorded mention as a Hindu port settlement in the 4th century. Ever since, the city had been variously claimed by the Indianized kingdom of Tarumanegara, Hindu Kingdom of Sunda, Muslim Sultanate of Banten, Dutch East Indies, Empire of Japan, and finally Indonesia.

Jakarta has been known under several names: Sunda Kelapa during the Kingdom of Sunda period; Jayakarta, Djajakarta or Jacatra during the short period of Banten Sultanate; Batavia, under the Dutch colonial empire; and Djakarta or Jakarta during the Japanese occupation and the modern period[1][2][3]

The early kingdoms (4th century AD)

The earliest recorded mention of Jakarta is as a port of origin that can be traced to a Hindu settlement as early as the 4th century. The Jakarta area was part of the fourth century Indianized kingdom of Tarumanagara. In AD 397, King Purnawarman established Sunda Pura as a new capital city for the kingdom, located at the northern coast of Java.[4] Purnawarman left seven memorial stones across the area with inscriptions bearing his name, including the present-day Banten and West Java provinces.[5]

The Kingdom of Sunda (669–1579)

After the power of Tarumanagara declined, its territories became part of the Kingdom of Sunda.

According to the Chinese source, Chu-fan-chi, written by Chou Ju-kua in the early 13th Century, Srivijaya ruled Sumatra, the Malay peninsula, and western Java (known as Sunda). The port of Sunda was described as strategic and thriving, pepper from Sunda being among the best in quality. The people worked in agriculture and their houses were built on wooden piles.[6]

One of the port at the mouth of a river was renamed Sunda Kelapa or Kalapa as written in a Hindu Bujangga Manik, a monk's lontar manuscripts, one of the precious remnants of Old Sundanese literature.[7] The port served Pakuan Pajajaran (present day Bogor), the capital of the Sunda Kingdom. By the fourteenth century, Sunda Kelapa became a major trading port for the kingdom.

The Portuguese and the Muslim Sultanates (16th century)

In 1513 the first European fleet, four Portuguese ships under the command of Alvin, arrived in Sunda Kelapa from Malacca. Malacca had been conquered in 1511 by Afonso de Albuquerque. The Portuguese were planning to establish a port in Sunda Kelapa as a relay route to the Moluccas, the famed "Spice Islands", in search of the black pepper.[8]

Some years later, the Portuguese Enrique Leme visited Kalapa with presents for the King of Sunda. He was well received and on August 21, 1522 and signed a treaty of friendship between the kingdom of Sunda and Portugal through the Luso Sundanese padrão. The treaty allowed the Portuguese to build a godown and to erect a fort in Kalapa. This was regarded by the Sundanese as a consolidation of their position against the raging Muslim troops from the rising power of the Sultanate of Demak in Central Java.[9]

In 1527, Muslim troops coming from Cirebon and Demak attacked the Kingdom of Sunda under the leadership of Fatahillah. The king was expecting the Portuguese to come and help them hold Fatahillah's army because of an agreement that had been in place between Sunda and the Portuguese. However, Fatahillah's army succeeded in conquering the city on June 22, 1557, and Fatahillah changed the name of Sunda Kelapa to Jayakarta (जयकर्; "Great Deed" or "Complete Victory" in Sanskrit), also written as Djajakarta or Jacatra.[9]

The East India Company (early 17th century)

In late 16th century, Jayakarta was ruled under the Sultanate of Banten. Prince Jayawikarta, a follower of the Sultan of Banten, established a settlement on the west banks of the Ciliwung river. He erected a military post there in order to control the port at the mouth of the river.[9]

In 1595, merchants from Amsterdam set up an expedition to the East Indies archipelago. Under the command of Cornelis de Houtman, the expedition arrived in Jayakarta in 1596 with the intention of trading spices; more or less the same as that of the Portuguese.[9]

Meanwhile in 1602, the English East India Company's first voyage, commanded by Sir James Lancaster, arrived in Aceh and sailed on to Bantam, the capital of the Sultanate of Banten, where he was allowed to build trading post which becomes the centre of English trade in Indonesia until 1682.[10]

In 1610, the Dutch merchants were granted permission to build a wooden godown and some houses just opposite of Prince Jayawikarta settlement on the east bank of the river.[9] As the Dutch grew more and more powerful, Jayawikarta allowed the British to erect houses on the West Bank of Ciliwung River and a fort close to his Customs Office post to keep his strength equal to that of the Dutch. Jayawikarta was in support of the British because his palace was under the threat of the Dutch cannons. In December 1618, the tense relationship between Prince Jayawikarta and the Dutch escalated. Jayawikarta soldiers besieged the Dutch fortress that covered two strong godown, namely Nassau and Mauritius. The British fleet made up of 15 ships arrived. The fleet was under the leadership of Sir Thomas Dale, an English naval commander and former governor of the Colony of Virginia (present State of Virginia).[9]

After the sea battle, the newly appointed Dutch governor Jan Pieterszoon Coen (1618) escaped to the Moluccas to seek support (where the Dutch had already took the first of the Portuguese forts in 1605). Meanwhile, the commander of the Dutch army, Pieter van den Broecke, along with five other men, was arrested when the negotiation was underway because Jayawikarta felt that he was deceived by the Dutch.[11] Later, Jayawikarta and the British entered into a friendship agreement.[9]

The Dutch army was about to surrender to the British when in 1619, a sultan from Banten sent soldiers and summoned Prince Jayawikarta, asking his responsibility for establishing closed realtionship with the British without first asking an approval from Banten authorities. The conflict between Banten and Prince Jayawikarta as well as the tensed relationship between Banten and the British had given a new opportunity for the Dutch. Relieved by the change in situation, the Dutch army, under the leadership of Jan Pieterszoon Coen, attacked and burned the city of Jayakarta and its Palace on May 30, 1619 without any opposition. The population of Jayakarta was expelled. There were no remains of Jayakarta except for the Padrão of Sunda Kelapa which were discovered much later in 1918 during an excavation for a new house in Kota area on the corner of Cengkeh street and Nelayan Timur Street, and is now stored at the National Museum in Jakarta. The location of Jayakarta was possibly located in Pulau Gadung.[9] Prince Jayawikarta retired to Tanara in the interior of Banten and died there. The Dutch established a closer relationship with Banten, took control of the port and so the Dutch East Indies ruled the entire region.[9]

The Dutch East India Company (17th - 18th century)

The Dutch fortress garrison, along with hired soldiers from Japan, Germany, Scotia, Denmark, and Belgium held a party in commemoration for their triumph. The godowns of Nassau and Mauritius were demolished and a new fort was erected by Commander Van Raay on March 12.[12] Coen wished to name the new settlement Nieuw-Hoorn (after his birthplace Hoorn), but after his birthplace, but he was not allowed by the central government of the Netherlands East Indies, the Heeren XVII, and instead Batavia was the new name for the fort and the new settlement, after the Germanic tribe of the Batavi, believed to be the ancestor of the Dutch people during that time. Since then Jayakarta was called Batavia for more than 300 years.[9]

Ever since its foundation in 1619, the Javanese people were unwelcomed in Batavia, because of the feared possibility that they would rise against the Dutch. Coen asked Bontekoe, a skipper for the Dutch East India Company, to brought 1000 Chinese people from Macao to Batavia. Only several dozens survived the trip. In 1621, 15,000 people were deported from Banda Islands to Batavia, only 600 survived the trip.

On August 27, 1628, Sultan Agung, king of the Mataram Sultanate (1613-1645), launched his first offensive on Batavia in 1628. He suffered heavy losses, retreated, and launch a second offensive in 1629. The Dutch fleet destroyed his supplies and his ships in the harbours of Cirebon and Tegal. Mataram troops, starving and decimated by illness, retreated again. Later, Sultan Agung pursued his conquering ambitions to the east. He attacked Blitar, Panarukan and the Blambangan principality in Eastern Java, a vassal of the Balinese kingdom of Gelgel.

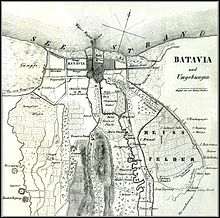

After the siege, it was decided that Batavia woule need a stronger defense system. Simon Stevin, a Flemish mathematician and a military engineer, were employed to design a walled city. His response it a typical Dutch city criss crossed with a canal and straightening the flow of river Ciliwung. Jacques Specx further developed the design by creating a moat and city wall which surrounded the city. In 1646, a system of four canals channeled from the Ciliwung River were established in Batavia. City walls were also built to protect the inhabitants of Batavia. Only the Chinese people and the Mardijkers were allowed to settle within the walled city of Batavia.

In 1656, because of a conflict with Banten, the Javanese were not allowed to reside within the city walls and they decided to settle outside Batavia. In 1659, a temporary peace with Banten enable the city to grew. During this period, more bamboo shacks appeared in Batavia. From 1667, bamboo houses within the city were banned, as well as the keeping of livestock. Because the city attracted many poeple, suburbs began to emerged outside the city walls.

The outside was considered unsafe for the non-native inhabitant of Batavia. Only when a new peace treaty was signed with banten in 1684 then the marsh area around Batavia can be fully cultivated. Country houses were established outside the city walls. The Chinese people made a start with the cultivation of sugarcane and tuak.

The large scale cultivation caused destruction on the environment. There was coastal erosion in the northern area of Batavia. Maintenance of the canal was extensive, because the canals were easily deposited and need to be continuously dredged. The marshy area around Batavia was a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes. In the 18th century, Batavia became increasingly affected by malaria epidemics. Many Europeans which arrived in Batavia would die because of illness caught in Batavia, giving a nickname to Batavia "Het kerkhof der Europeanen", "the cemetery of the Europeans".[13] Those who could afford moved to higher areas to the south. Eventually, the old city will finally be dismantled in 1810.

Batavia was founded as a trade and administrative center of the Dutch East India Company, and was never intended as a settlement company for the Dutch people. Coen founded Batavia to be a trading company in the form of a city filled with people who would took care of the production and the supply of food. As a result, there were no migration of Dutch families. Instead a mixed society was formed.

There were few Dutch women in Batavia. Dutch men often came into contact with Asian women without marrying them because of the fact that the women could not return to the Republic. This societal pattern created a group of mestizo descendants in Batavia. The sons of this mixed group often went to Europe to study, while the daughters had to remain in Batavia. This group of daughters often married a VOC officials at a very young age. Because the women always stayed in Batavia, they were important in the social networking in Batavia. They were accustomed to deal with slaves and spoke their language, mostly Portuguese and Malay. Many of these women were often widows, especially when their husband decided to leave Batavia to Netherlands and often they had to give up their children. These women were known as snaar (“string”) during those time.

Since the VOC wanted to organized everything on their own, they decided to keep as little as free citizens as possible and employed many slaves. Batavia became an unattractive location for people who wanted to establish their own business.

Most of the residents of Batavia were of Asian descent. There were thousands of slaves brought from India and Arakan. Later, slaves were brought from Bali and Sulawesi. To avoid uprising, it was decided that the Javanese should not be kept as slaves. Chinese people made up the largest group in Batavia, most of them are merchants and laborers. The Chinese people were the most decisive group in the development of Batavia. There was also a large group of freed slaves, usually Portuguese-speaking Asian Christians who were formerly slaves to the Portuguese. They were made prisoners by the VOC in the many conflicts with the Portuguese. Portuguese was the dominant language in Batavia until late 18th century, when the language was slowly replaced with Dutch and Malay. Additionally, there were also Muslim and Hindu merchants from India and Malays.

Initially, these different ethnic groups live side by side. In 1688, complete segregation was enacted to the indigenous population. Each ethnic group had to live in their own established village outside the city wall. There were Javanese village for Javanese people, Moluccan village for the Moluccans, and so on. Each people were tagged with a lead identity tag to identify them with their own ethnic group. Later, this identity tag was replaced with a parchment. Intermarriage between different ethnic groups should be reported.

Within Batavia's walls, wealthy Dutch built tall houses and canals. Commercial opportunities attracted Indonesian and especially Chinese immigrants, the increasing numbers creating burdens on the city. Tensions grew as the colonial government tried to restrict Chinese migration through deportations. On 9 October 1740, 5,000 Chinese were massacred and the following year, Chinese inhabitants were moved to Glodok outside the city walls.[14]

In the 18th century, more than 60% population of Batavia were slaves working for the VOC. They mostly did the housework. Working and living conditions were generally reasonable. There were laws that protected them against an overly cruel action from their masters. Christian slaves were given freedom after the death of their master. Some slaves were allowed to own a store and made money to free themselves. Sometimes, slaves fled and established gangs roaming the area, creating an unsafe environment around Batavia.

From the beginning of the VOC establishment in Batavia until the colony became a fully fledged town, the population of Batavia grew tremendously. At the beginning, Batavia had around 50,000 inhabitants. In the second half of the 19th century, Batavia had 800,000 inhabitants. By the end of the VOC rule of Batavia, the population of Batavia reached one million.[15]

Modern colonialism (19th century - 1942)

After the VOC was formally liquidated in 1800 the Batavian Republic expanded all the VOC's territorial claims into a fully fledged colony named the Dutch East Indies. From the company's regional headquarters Batavia now evolved into the capital of the colony. During this era of both urbanisation and industrialisation Batavia was at the inceptive stage of most modernising developments in the colony.

In 1808 Daendels decided to quit the by then dilapidated and unhealthy Old Town and build a new town center further to the south, near the estate of Weltevreden. Batavia had thus become a city with two centers: Kota as the hub of business, where the offices and warehouses of shipping and trading companies were located, while Weltevreded became the new home for the government, military, and shops. These two centers were connected by the Molenvliet Canal and a road (now Gajah Mada Road) which ran alongside it.[16] This period in the 19th century shows many technological advancement and city beautification in Batavia, earning Batavia a nickname "De Koningin van het Oosten", "Queen of the East".

The city began to move further south as epidemics in 1835 and 1870 encouraged more people to move far south of the port.

By the end of the century the capital and regency of Batavia numbered 115,887 people of which 8,893 were Europeans, 26,817 Chinese and 77,700 indigenous islanders.[17] Many schools, hospitals, factories, offices, trading companies, and post offices were established throughout the city. Improvements in transportation, health, and technology in Batavia caused more and more Dutch people to migrate to Batavia, making the society of Batavia becoming more and more Dutch like. These Dutch people who never set their foot on Batavia were known locally Totoks. The term totok was also used to identify a new Chinese arrivals, to differentiate them with the Peranakan. Many totoks developed a great love for the Indies culture of Indonesia and adopted this culture. They would wear a kebaya, a sarong, and a summer dress.[18]

In Indonesian National Revival era, Mohammad Husni Thamrin, a member of Volksraad criticized the Colonial Government for ignoring the development of kampung (inlander's area) while focusing the development for the rich people in Menteng. He also talked on the issue of Farming Tax and other taxes which burdened people. Some of his speeches are still relevant in today's Jakarta.

The consequence of these expanding commercial activities was the immigration of large numbers of Dutch employees as well as rural Javanese into Batavia. In 1905, the population of Batavia and around the area reached a tremendous 2.1 million, including 93,000 Chinese people, 14,000 Europeans, and 2,800 Arabs, as well as local population.[15] This resulted in a great demand for housing and land prices soared. New houses were often built closely packed together with kampung settlements filling the spaces in between. This development with little regard for the tropical conditions resulted in too many people living too close together, in houses with poor sanitation and no public amenities. In 1913, the plague broke out in Java.[16] During this period, the Old Batavia, with its abandoned moats and ramparts, experienced a new boom as the commercial companies established themselves along the Kali Besar once more. In a very short period, the area of Old Batavia reestablished itself as a new commercial center with 20the century buildings and 17th century buildings standing side by side.

See also List of colonial buildings and structures in Jakarta

Technological advancement in 19th century Batavia

19th century proven as the Golden Age of Batavia, with many technological advancement especially in the transportation and health sector. Below are the list of important points in the history of Batavia.

1836 the first Steamboat arrived at the Batavia shipyard of Island Onrust.

1853 the first exhibition of agricultural products and native arts & crafts was held in Batavia.

1860 the Willem III school was openend.

1869 the Batavia Tramway Company started the horse-tram line nr 1: Old Batavia (now: Jakarta Kota). Route: From Amsterdam Gate at the northern end of Prinsenstraat (now: Jl Cengke) to Molenvliet (now: Jl Gaja Madah) and Harmonie. After 1882 the horse-tram lines were reconstructed into steamtram lines.[19] The electric train that ran from 1899 was the first electric train in the Kingdom of Netherlands.

The abolition of the Cultuurstelsel in 1870 made way for rapid development of private enterprise in the Dutch Indies. Numerous trading companies and financial institutions established themselves in Java, most of them settled in Batavia. Jakarta Old Town's deteriorating structures were replaced with offices, typically along the Kali Besar. These private companies owned or managed plantations, oil fields, and mines. Railway stations were designed during this period, with characteristic style of this period.[16]

1864 the concession for constructing the Batavia-Bogor railway was granted and completed in 1871.

1878 the first centenary of the Batavia Society of Arts & Sciences was celebrated.

International trade with Europe boomed, and the increase of shipping led to the construction of a new harbor at Tanjung Priok between 1877 and 1883.

1881 the first dry docks were opened on Island Amsterdam just off the Batavia roadsteads.

From 1881 to 1884 the railway infrastructure was expanded to connect Batavia to Sukabumi, Cianjur and Bandung. In 1886 the Batavia harbour was connected to the railway system. By 1894 Batavia was connected to Surabaya.[17]

1883 the Dutch Indies Telephone Company was established in Batavia.

1884 the first exhibition of Javanese arts & crafts at the Zoological gardens.

1888 the Anatomical and Bacterial Institute was established.

1895 the Pasteur Institute was established.[17]

Japanese Occupation

On March 5, 1942 Batavia fell to the Japanese troops. The Dutch formally surrendered to the Japanese occupation forces on March 9, 1942 and rule of the colony was transferred to Japan. The city was renamed Jakarta, with official name Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi (Special Municipality of Jakarta). This period was a period of decline in Batavia. During three and a half years of occupation, both the economic situation and the physical conditions of Indonesian cities deteriorated. Many buildings were vandalized as metal was needed for the war, many iron statues from the Dutch colonial period were taken away by the Japanese troops.[20]

To strengthen its position in Indonesia, the Japanese government issued an Act No. 42 1942 on the "Restoration of the Regional Administration System". This act divided Java into several Syuu (Resident Administration or Karesidenan), each was led by a Bupati (Regent). Each Syuu was divided into several Shi (Municipality or Stad Gemeente), led by a Wedana (District Head). Below a Wedana is a Wedana Assistant (Sub District Head), which in turn headed a Lurah (Village Unit Head), which in turn headed a Kepala Kampung (Kampung Chief).

Jakarta however was made a special status called Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi (Special Municipality of Jakarta) with a Schichoo (Mayor) heading all these officials, following the law created by the Guisenken (Head of the Japanese Troops Administration). The effect of this system was a one-man rule with no councils of representative bodies. The first schichoo of Jakarta is Tsukamoto, and the last is Hasegawa.[21]

In 1943, the Japanese Troops Administration slightly revised the administration of Jakarta by adding a special counseling body. This special counseling body was comprised of twelve local (Javanese) leaders who were regarded loyal to the Japanese, among them are Suwiryo and Dahlan Abdullah.[21]

National Revolution Era (1945-1950)

Since the proclamation of the independence of Indonesia on August 17, 1945, at Jalan Pegangsaan Timur No. 56 (now Jalan Proklamasi), Jakarta, Suwiryo still presented and acted as committee chairman. At that time, he was recognized as the first mayor of Jakarta Tokubetsu Shi (the name soon changed into Pemerintah Nasional Kota Jakarta, "Jakarta City National Administration". On November 21, 1945, Suwiryo and his assistants were arrested by the Netherlands Indies Civil Administration who had returned to their former colony.[21]

Following World War II, Indonesian Republicans withdrew from allied-occupied Jakarta during their fight for Indonesian independence and established their capital in Yogyakarta.

On December 27, 1949, the Dutch finally recognized Indonesia as an independent country and a sovereign federal state under the name of Republic of the United States of Indonesia. At this time, the Jakarta City Administration was led by Mayor Sastro Mulyono.

Early independence era (1950s-1960s)

Following the surrender of the Japanese, Indonesia declared its independence in 1945, but urban development continued to stagnate whilst the Dutch tried to reestablish themselves. In 1947, the Dutch succeeded in implementing a set of planning regulations for urban development - the SSO/SVV (Stadsvormings-ordonantie/Stadsvormings-verordening) - which had been drawn up before the war.

In 1950, the Dutch finally left and their residences and properties were taken over by the Indonesian government in 1957. Once independence was secured, Jakarta was once again made the national capital.[14] The departure of the Dutch caused a massive migration of the rural people into Jakarta in response to a perception that the city is the place for economic opportunities. The kampung areas swelled.

Indonesia's founding president, Sukarno, envisaged Jakarta as a great international city instigating large, government-funded projects undertaken with openly nationalistic architecture that strived to show the newly independent nation's pride in itself.[22] To promote nationalistic pride amongst Indonesian people, Sukarno interpreted his modernist ideas in his urban planning for the capital (eventually Jakarta). Many monumental projects of Sukarno are the clover-leaf highway, a broad by-pass in Jakarta (Jalan Jenderal Sudirman), four high-rise hotels including the Hotel Indonesia, a new parliament building, the Bung Karno Stadium, the largest mosque in Southeast Asia, and numerous monuments and memorials including The National Monument.

Kampung improvement program (1970s)

Since 1970, the national development policy has been focused primarily on economic growth and achievement. This situation encouraged the emergence of a large number of housing projects in the private sector. Government housing schemes have also been implemented to cope with the growth of urban populations. During this period, kampung improvement programmes have been reintroduced to improve conditions in existing areas. This Kampung Improvement Programme of Jakarta, enacted by Ali Sadikin, the governor of Jakarta (1966 to 1977), was a success. The program had won the 1980 Aga Khan Award for architecture in 1980. Ali Sadikin was also credited with rehabilitating public services, clearing out slum dwellers, banned rickshaws, and street peddlers.[14] Despite the huge success of this policy, they have been discontinued because they were considered to be too biased toward improving the physical infrastructure solely.[20]

Recent urban development (1980s - now)

During the 1980s, smaller sites have been acquired for high-rise projects, while larger parcels of land have been subdivided for low-key projects such as the building of new shophouses. This period also saw the removal of kampongs from the inner city areas and the destruction of many historical buildings.[20] One infamous case is the demolition of the Society of Harmonie to be turned into a parking.

The period between the late 1980s and the mid 1990s saw a massive increase in foreign investment as Jakarta became the focus of real estate boom. This enforcement of overseas capital into joing-venture property and construction projects with local developers brought many foreign architects to Indonesia. However, unlikt the Dutch architects of the 1930s, many of these expatriate architects were unfamiliar with the tropics, while their local partners had received a similar Modernist architectural training. As a result, downtown areas in Jakarta gradually came to resemble those of big cities in the West and often at a high environmental cost: massive high-rise buildings consume huge amounts of energy in terms of air-conditioning and other services.[20]

The period of Jakarta's economic boom ended abruptly in the 1997 East Asian Economic crisis. Many projects were left abandoned. The city became the centre of violence, protest, and political maneuvering as long-time president Suharto began to lose his grip on power. Tensions reached a peak in May 1998 when four students were shot dead at Trisakti University by security forces; four days of riots ensued resulting in an estimated 6,000 buildings damaged or destroyed, and the loss of 1,200 lives. The Chinese of the Glodok district were hardest hit and stories of rape and murder later emerged.[14] The following years Jakarta was the centre of popular protest and national political instability, including several terms of ineffective Presidents, and a number Jemaah Islamiah-connected bombings. Jakarta is now witnessing a period of political stability and prosperity along a boom in construction.

Notes and references

- ^ See also Perfected Spelling System as well as Wikipedia:WikiProject Indonesia/Naming conventions

- ^ http://www.omniglot.com/writing/indonesian.htm

- ^ http://www.studyindonesian.com/lessons/oldspellings/

- ^ Sundakala: cuplikan sejarah Sunda berdasarkan naskah-naskah “Panitia Wangsakerta” Cirebon. Yayasan Pustaka Jaya, Jakarta. 2005.

- ^ The Sunda Kingdom of West Java From Tarumanagara to Pakuan Pajajaran with the Royal Center of Bogor. Yayasan Cipta Loka Caraka. 2007.

- ^ Drs. R. Soekmono, (1973, 5th reprint edition in 1988). Pengantar Sejarah Kebudayaan Indonesia 2, 2nd ed. Yogyakarta: Penerbit Kanisius. pp. page 60.

{{cite book}}:|pages=has extra text (help); Check date values in:|date=(help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ Bujangga Manik Manuscript which are now located at the Bodleian Library of Oxford University in England, and travel records by Prince Bujangga Manik.(Three Old Sundanese Poems. KITLV Press. 2007.)

- ^ Sumber-sumber asli sejarah Jakarta, Jilid I: Dokumen-dokumen sejarah Jakarta sampai dengan akhir abad ke-16. Cipta Loka Caraka. 1999.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "History of Jakarta". BeritaJakarta.com. The Jakarta City Administration. 2002. Retrieved August 16, 2011.

- ^ Ricklefs, Merle Calvin. (1993). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1300, p. 29.

- ^ http://www.kitlv-journals.nl/index.php/btlv/article/viewFile/5535/6302

- ^ http://www.vocsite.nl/geschiedenis/handelsposten/batavia.html

- ^ van Emden,, F. J. G. (1964). Willem Brandt (ed.). Kleurig memoriaal van de Hollanders op Oud-Java. A. J. G. Strengholt. p. 146.

{{cite book}}: Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help)CS1 maint: extra punctuation (link) - ^ a b c d Witton, Patrick (2003). Indonesia, p. 101.

- ^ a b Oosthoek's Geïllustreerde Encyclopaedie (1917)

- ^ a b c Gunawan Tjahjono, ed. (1998). Architecture. Indonesian Heritage. Vol. 6. Singapore: Archipelago Press. ISBN 981-3018-30-5.

- ^ a b c Teeuwen, Dirk Rendez Vous Batavia (Rotterdam, 2007)

- ^ Nordholt, Henk Schulte (2005). Outward appearances: trend, identitas, kepentingan (in Indonesian). PT LKiS Pelangi Aksara. p. 227. ISBN 9799492955, 9789799492951. Retrieved August 20, 2011.

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Unknown parameter|coauthors=ignored (|author=suggested) (help) - ^ Teeuwen, Dirk Rendez Vous Batavia From horsepower to electrification. Tramways in Batavia-Jakarta, 1869–1962. (Rotterdam, 2007) [1]

- ^ a b c d Cite error: The named reference

heritage6was invoked but never defined (see the help page). - ^ a b c Jakarta Dalam Angka - Jakarta in Figures - 2008. Jakarta: BPS - Statistics DKI Jakarta Provincial Office. 2008. pp. xlvii–xlix. ISBN [[Special:BookSources/ISSN 0215-2150|'"`UNIQ--templatestyles-0000003E-QINU`"'[[ISSN (identifier)|ISSN]] [https://www.worldcat.org/search?fq=x0:jrnl&q=n2:0215-2150 0215-2150]]].

{{cite book}}: Check|isbn=value: invalid character (help); Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help); External link in|isbn=|isbn=at position 1 (help) - ^ Schoppert, Peter et al. (1997). Java Style, p. _.

Other readings

- Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (1993), A History of Modern Indonesia Since c.1300, Stanford: Stanford University Press, ISBN 0804721947.

- Schoppert, Peter; Damais, Soedarmadji; Sosrowardoyo, Tara (1998), Java Style, Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, ISBN 9625932321

{{citation}}: Unknown parameter|lastauthoramp=ignored (|name-list-style=suggested) (help). - Witton, Patrick (2003), Indonesia, Melbourne: Lonely Planet, ISBN 1740591542.

External links

- Pictures and Map from 1733 (Homannische Erben, Nuernberg-Germany) [2]