Military history of the United States during World War II: Difference between revisions

→Combat experience: link |

→Island hopping: airfields |

||

| Line 89: | Line 89: | ||

===Island hopping=== |

===Island hopping=== |

||

Following the resounding victory at Midway, the United States began a major land offensive. The Allies came up with a strategy known as [[Leapfrogging (strategy)|Island hopping]], or the bypassing of islands that served little or no strategic importance.<ref>[http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1671.html "Pacific Theater, World War II — Island Hopping, 1942-1945"], USHistory.com.</ref> Because air power was crucial to any operation, only islands that could support airstrips were targeted by the Allies. The fighting for each island in the Pacific Theater would be savage, as the Americans faced a determined and battle-hardened enemy who had known little defeat on the ground. |

Following the resounding victory at Midway, the United States began a major land offensive. The Allies came up with a strategy known as [[Leapfrogging (strategy)|Island hopping]], or the bypassing of islands that served little or no strategic importance.<ref>[http://www.u-s-history.com/pages/h1671.html "Pacific Theater, World War II — Island Hopping, 1942-1945"], USHistory.com.</ref> Because air power was crucial to any operation, only islands that could support airstrips were targeted by the Allies. The fighting for each island in the Pacific Theater would be savage, as the Americans faced a determined and battle-hardened enemy who had known little defeat on the ground. |

||

====Building airfields==== |

|||

The goal of island hopping was to build forward air fields. AAF commander General Hap Arnold correctly anticipated that he would have to build forward airfields in inhospitable places. Working closely with the Army Corps of Engineers, he created Aviation Engineer Battalions that by 1945 included 118,000 men; it operated in all theatres. Runways, hangers, radar stations, power generators, barracks, gasoline storage tanks and ordnance dumps had to be built hurriedly on tiny coral islands, mud flats, featureless deserts, dense jungles, or exposed locations still under enemy artillery fire. The heavy construction gear had to be imported, along with the engineers, blueprints, steel-mesh landing mats, prefabricated hangars, aviation fuel, bombs and ammunition, and all necessary supplies. As soon as one project was finished the battalion would load up its gear and move forward to the next challenge, while headquarters inked in a new airfield on the maps. Heavy rains often reduced the capacity of old airfields, so new ones were built. Often engineers had to repair and use a captured enemy airfield. Unlike the well-built German air fields in Europe, the Japanese installations were ramshackle affairs with poor siting, poor drainage, scant protection, and narrow, bumpy runways. Engineering was a low priority for the offense-minded Japanese, who chronically lacked adequate equipment and imagination. <ref>Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, ''The Army Air Forces In World War II: Vol 7: Services Around The World'' (1958) ch 10</ref> |

|||

====Guadalcanal==== |

====Guadalcanal==== |

||

{{Main|Battle of Guadalcanal}} |

{{Main|Battle of Guadalcanal}} |

||

Revision as of 02:15, 5 August 2011

The military history of the United States during World War II covers the involvement of the United States during World War II. The Empire of Japan declared war on the United States of America on 7 December 1941, immediately after the attack on Pearl Harbor on the same day.[1] On 11 December 1941, Germany and Italy also declared war on the United States. Until that time, the United States had maintained neutrality, although it had, since March that same year, supplied the British with war materiel through the Lend-Lease Act. The British then went on to supply a significant part of that aid to the Soviet Union and its Western Allies. Between the entry of the United States on 8 December 1941 and the end of the war in 1945, over 16 million Americans served in the United States military.[2] Many others served with the Merchant Marine [3] and paramilitary civilian units like the WASPs.

Isolationism

Following the Treaty of Versailles, and the refusal of the United States to enter the League of Nations, public sentiment in the United States shifted toward a hesitation to become involved in European affairs.[4] After World War I, the U.S. had withdrawn its forces and had stated that they would never return. The Great Depression had also crippled the economy, forcing the United States to neglect its military and focus on other concerns.

Lend-Lease

Without American production the United Nations could never have won the war.

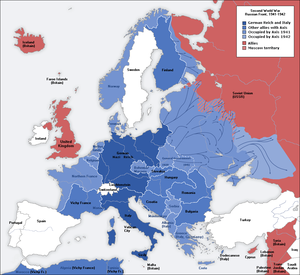

The year 1940 marked a change in attitude in the United States. The German victories in France, Poland and elsewhere, combined with the Battle of Britain, led many Americans to believe that the United States would be forced to fight soon. On March 11, 1941, President Franklin Roosevelt signed the Lend-Lease Act, which committed much-needed American weapons to the Allied effort against the Axis Powers, since much British heavy equipment had been abandoned during their evacuation of Dunkirk.[6] While not an official declaration of war on the part of the United States, Lend-Lease could be described as a display of US Government sympathies but not US public opinion.

By 1941 the United States was taking an increasing part in the war, despite its nominal neutrality. In April 1941 President Roosevelt extended the Pan-American Security Zone east almost as far as Iceland. British forces had occupied Iceland when Denmark fell to the Germans in 1940; the US was persuaded to provide forces to relieve British troops on the island. American warships began escorting Allied convoys in the western Atlantic as far as Iceland, and had several hostile encounters with U-boats.

The first time Americans engaged in hostile action after September 1, 1939 was on April 10, 1941, when the destroyer USS Niblack attacked a German U-boat that had just sunk a Dutch freighter. The Niblack was picking up survivors of the freighter when it detected the U-boat preparing to attack. The Niblack attacked with depth charges and drove off the U-boat. There were no casualties onboard the Niblack or the U-boat.

In June 1941 the US realized that the tropical Atlantic became dangerous for unescorted American merchant vessels as well. On May 21, the SS Robin Moor, an American vessel carrying no military supplies, had been stopped by U-69 750 miles (1,210 km) west of Freetown, Sierra Leone. After its passengers and crew were allowed thirty minutes to board lifeboats, U-69 torpedoed, shelled and sank the ship. The survivors then drifted without rescue or detection for up to eighteen days.

One could argue that either the casualties inflicted on USS Kearny by U-boat U-568 on October 17, 1941 or the sinking of the USS Reuben James by U-552 on October 31, 1941 might be considered the first American losses of World War II.

Attack on Pearl Harbor

Because of Japanese actions in French Indochina and China, the United States imposed numerous sanctions, including an oil and scrap metal embargo. The oil embargo threatened to grind the Japanese military machine to a halt. Fearing a shortage of resources, and that war with the United States was inevitable, the Japanese decided to take action against the United States Pacific Fleet stationed at Pearl Harbor. President Roosevelt had months earlier transferred the American fleet there from San Diego in order to present a deterrent to any possible Japanese attack. Shortly after negotiations in Washington broke down, the Japanese launched a full scale surprise attack at Pearl Harbor on the morning of 7 December 1941. While the attack succeeded in sinking and damaging many battleships, the American aircraft carriers were not present, preserving American force projection capabilities.[7]

Pacific Theater

Following the attack on Pearl Harbor, President Roosevelt officially asked for a declaration of war on Japan before a joint session of Congress on 8 December 1941. This notion passed with only one vote against in both chambers.

Battle of the Philippines

The day after their attack at Pearl Harbor, the Japanese launched an offensive into the American occupied Philippines. Much of the U.S. Far East Air Force was destroyed on the ground by the Japanese. Soon, all American and Filipino forces were forced onto the isolated Bataan peninsula, and General Douglas MacArthur, commander of Allied troops in the Philippines, was ordered to evacuate the area by President Roosevelt. MacArthur finally did in March 1942, fleeing to Australia, where he commanded the defense of that island. His famous words, "I came out of Bataan and I shall return," would not become true until 1944. Before leaving, MacArthur had placed Major General Jonathan M. Wainwright in command of the defense of the Philippines. After fierce fighting, Wainwright surrendered the combined American and Filipino force to the Japanese on 8 May with the hope that they would be treated fairly as POW's. They were not, and they suffered greatly through the Bataan Death March and Japanese prison camps.

Battle of Wake Island

At the same time as the attack on the Philippines, a group of Japanese bombers flown from the Marshall Islands destroyed many of the Marine Corps fighters on the ground at Wake Island in preparation for the Japanese invasion. The first landing attempt was disastrous for the Japanese; the heavily outnumbered and outgunned American Marines and civilians sent the Japanese fleet in retreat with the support of the only four remaining F4F fighters, piloted by Marines. The second attack was far more successful for the Japanese; the outnumbered Americans were forced to surrender after running low on supplies.

Dutch East Indies campaign

After their initial successes, the Japanese headed for the Dutch East Indies to gain its rich oil resources. To coordinate the fight against the Japanese, the American, British, Dutch, and Australian forces combined all available land and sea forces under the American-British-Dutch-Australian Command (ABDACOM or ABDA) banner on January 15, 1942. The ABDACOM Fleet, being outnumbered by the Japanese fleet and without air support, was defeated very quickly in several naval battles around Java. The isolated ground forces followed soon, leading to the occupation of Indonesia until the end of the war. After this disastrous defeat the ABDA Command was dissolved again.

Solomon Islands and New Guinea Campaign

Following their rapid advance, the Japanese started the Solomon Islands Campaign from their newly conquested main base at Rabaul in January 1942. The Japanese seized several islands including Tulagi and Guadalcanal, before they were halted by further events leading to the Guadalcanal Campaign. This campaign also converged with the New Guinea campaign.

Battle of the Coral Sea

In May 1942, the United States fleet engaged the Japanese fleet during the first battle in history in which neither fleet fired directly on the other, nor did the ships of both fleets actually see each other. It was also the first time that aircraft carriers were used in battle. While indecisive, it was nevertheless a turning point because American commanders learned the tactics that would serve them later in the war.

Battle of the Aleutian Islands

The Battle of the Aleutian Islands was the last battle between sovereign nations to be fought on American soil. As part of a diversionary plan for the Battle of Midway, the Japanese took control of two of the Aleutian Islands. Their hope was that strong American naval forces would be drawn away from Midway, enabling a Japanese victory. Because their ciphers were broken, the American forces only drove the Japanese out after Midway.

Combat experience

Airmen flew far more often in the Southwest Pacific than in Europe, and although rest time in Australia was scheduled, there was no fixed number of missions that would produce transfer out of combat, as was the case in Europe. coupled with the monotonous, hot, sickly environment, the result was bad morale that jaded veterans quickly passed along to newcomers. After a few months, epidemics of combat fatigue (now called Combat stress reaction) would drastically reduce the efficiency of units. The men who had been at jungle airfields longest, the flight surgeons reported, were in bad shape:

- Many have chronic dysentery or other disease, and almost all show chronic fatigue states. . . .They appear listless, unkempt, careless, and apathetic with almost masklike facial expression. Speech is slow, thought content is poor, they complain of chronic headaches, insomnia, memory defect, feel forgotten, worry about themselves, are afraid of new assignments, have no sense of responsibility, and are hopeless about the future."[8]

Battle of Midway

Having learned important lessons at Coral Sea, the United States Navy was prepared when the Japanese navy under Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto launched an offensive aimed at destroying the American Pacific Fleet at Midway Island. The Japanese hoped to embarrass the Americans after the humiliation of the Doolittle Raid on Tokyo. Midway was a strategic island that both sides wished to use as an air base. Yamamoto hoped to achieve complete surprise and a quick capture of the island, followed by a decisive carrier battle with which he could completely destroy the American carrier fleet. Before the battle began, however, American intelligence intercepted his plan, allowing Admiral Chester Nimitz to formulate an effective defensive ambush of the Japanese fleet.[9] The battle began on 4 June 1942. By the time it was over, the Japanese had lost four carriers, as opposed to one American carrier lost. The Battle of Midway was the turning point of the war in the Pacific because the United States had seized the initiative and was on the offensive for the duration of the war.

Island hopping

Following the resounding victory at Midway, the United States began a major land offensive. The Allies came up with a strategy known as Island hopping, or the bypassing of islands that served little or no strategic importance.[10] Because air power was crucial to any operation, only islands that could support airstrips were targeted by the Allies. The fighting for each island in the Pacific Theater would be savage, as the Americans faced a determined and battle-hardened enemy who had known little defeat on the ground.

Building airfields

The goal of island hopping was to build forward air fields. AAF commander General Hap Arnold correctly anticipated that he would have to build forward airfields in inhospitable places. Working closely with the Army Corps of Engineers, he created Aviation Engineer Battalions that by 1945 included 118,000 men; it operated in all theatres. Runways, hangers, radar stations, power generators, barracks, gasoline storage tanks and ordnance dumps had to be built hurriedly on tiny coral islands, mud flats, featureless deserts, dense jungles, or exposed locations still under enemy artillery fire. The heavy construction gear had to be imported, along with the engineers, blueprints, steel-mesh landing mats, prefabricated hangars, aviation fuel, bombs and ammunition, and all necessary supplies. As soon as one project was finished the battalion would load up its gear and move forward to the next challenge, while headquarters inked in a new airfield on the maps. Heavy rains often reduced the capacity of old airfields, so new ones were built. Often engineers had to repair and use a captured enemy airfield. Unlike the well-built German air fields in Europe, the Japanese installations were ramshackle affairs with poor siting, poor drainage, scant protection, and narrow, bumpy runways. Engineering was a low priority for the offense-minded Japanese, who chronically lacked adequate equipment and imagination. [11]

Guadalcanal

The first major step in their campaign was the Japanese occupied island of Guadalcanal in the Solomon Islands chain. Marines from the 1st Marine Division and soldiers from the Army XIV Corps landed on Guadalcanal near the Tenaru River on 7 August 1942. They quickly captured Henderson Field, and prepared defenses. On what would become known as the Battle of Bloody Ridge, the Americans held off wave after wave of Japanese counterattacks before charging what was left of the Japanese. After more than six months of combat the island was firmly in control of the Allies on 8 February 1943.

Tarawa

Guadalcanal made it clear to the Americans that the Japanese would fight to the bitter end. After brutal fighting in which few prisoners were taken on either side, the United States and the Allies pressed on the offensive. The landings at Tarawa on 20 November 1943, by the Americans became bogged down as armor attempting to break through the Japanese lines of defense either sank, were disabled or took on too much water to be of use. The Americans were eventually able to land a limited number of tanks and drive inland. After days of fighting the Allies took control of Tarawa on 23 November. Of the original 2,600 Japanese soldiers on the island, only 17 were still alive.

Operations in Central Pacific

In preparation of the recapture of the Philippines, the Allies started the Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign to retake the Gilbert and Marshall Islands from the Japanese in summer 1943. After this success, the Allies went on and retook the Mariana and Palau Islands in summer 1944.

Liberation of the Philippines

General MacArthur fulfilled his promise to return to the Philippines by landing at Leyte on 20 October 1944. The Allied re-capture of the Philippines took place from 1944 to 1945 and included the battles of Leyte, Leyte Gulf, Luzon, and Mindanao.

Iwo Jima

The island of Iwo Jima and the critical airstrips there served as the next area of battle. The Japanese had learned from their defeat at the Battle of Saipan and prepared many fortified positions on the island, including pillboxes and underground tunnels. The American attack began on 19 February 1945. Initially the Japanese put up little resistance, letting the Americans mass, creating more targets before the Americans took intense fire from Mount Suribachi and fought throughout the night until the hill was surrounded. Even as the Japanese were pressed into an ever shrinking pocket, they chose to fight to the end, leaving only 1,000 of the original 21,000 alive. The Allies suffered as well, losing 7,000 men, but they were victorious again, however, and reached the summit of Mount Suribachi on 23 February. It was there that five Marines and one Navy Corpsman famously planted the American flag.

Okinawa

Okinawa became the last major battle of the Pacific Theater and the Second World War. The island was to become a staging area for the eventual invasion of Japan since it was just 350 miles (550 km) south of the Japanese mainland. Marines and soldiers landed unopposed on 1 April 1945, to begin an 82-day campaign which became the largest land-sea-air battle in history and was noted for the ferocity of the fighting and the high civilian casualties with over 150,000 Okinawans losing their lives. Japanese kamikaze pilots enacted the largest loss of ships in U.S. naval history with the sinking of 38 and the damaging of another 368. Total U.S. casualties were over 12,500 dead and 38,000 wounded, while the Japanese lost over 110,000 men. The fierce fighting on Okinawa is said to have played a part in President Truman’s decision to use the atomic bomb and to forsake an invasion of Japan.

Hiroshima and Nagasaki

As victory for the United States slowly approached, casualties mounted. A fear in the American high command was that an invasion of mainland Japan would lead to enormous losses on the part of the Allies, as casualty estimates for the planned Operation Downfall demonstrate. President Harry Truman gave the order to drop the first atomic bomb on Hiroshima on 6 August 1945, hoping that the destruction of the city would break Japanese resolve and end the war. A second bomb was dropped on Nagasaki on 9 August, after it appeared that the Japanese high command was not planning to surrender. Approximately 140,000 people died in Hiroshima from the bomb and its aftereffects by the end of 1945, and approximately 74,000 in Nagasaki, in both cases mostly civilians.

15 August 1945, or V-J Day, marked the end of the United States' war with the Empire of Japan. Since Japan was the last remaining Axis Power, V-J Day also marked the end of World War II.

Minor American front

The United States contributed several forces to the China Burma India theater, such as a volunteer air squadron (later incorporated into the Army Air Force), and Merrill's Marauders, an infantry unit. The U.S. also had an adviser to Chiang Kai-shek, Joseph Stillwell.

European and North African Theaters

On 11 December 1941, Adolf Hitler and Nazi Germany declared war on the United States, the same day that the United States declared war on Germany and Italy.[12]

Europe first

The established grand strategy of the Allies was to defeat Germany and its allies in Europe first, and then focus could shift towards Japan in the Pacific. This was because two of the Allied capitals (London and Moscow) could be directly threatened by Germany, but none of the major Allied capitals were threatened by Japan.

Operation Torch

The United States entered the war in the west with Operation Torch on 8 November 1942, after their Russian allies had pushed for a second front against the Germans. General Dwight Eisenhower commanded the assault on North Africa, and Major General George Patton struck at Casablanca.

Allied victory in North Africa

The United States did not have a smooth entry into the war against Nazi Germany. Early in 1943, the U.S. Army suffered a near-disastrous defeat at the Battle of the Kasserine Pass in February. The senior Allied leadership was primarily to blame for the loss as internal bickering between American General Lloyd Fredendall and the British led to mistrust and little communication, causing inadequate troop placements.[13] The defeat could be considered a major turning point, however, because General Eisenhower replaced Fredendall with General Patton.

Slowly the Allies stopped the German advance in Tunisia and by March were pushing back. In mid April, under British General Bernard Montgomery, the Allies smashed through the Mareth Line and broke the Axis defense in North Africa. On 13 May 1943, Axis troops in North Africa surrendered, leaving behind 275,000 men. Allied efforts turned towards Sicily and Italy.

Invasion of Sicily and Italy

The first stepping stone for the Allied liberation of Europe was, in Prime Minister Winston Churchill's words, the "soft underbelly" of Europe on the Italian island of Sicily. Launched on 9 July 1943, Operation Husky was, at the time, the largest amphibious operation ever undertaken. The operation was a success, and on 17 August the Allies were in control of the island.

Following the Allied victory in Sicily, Italian public sentiment swung against the war and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini. He was deposed in a coup, and the Allies struck quickly, hoping resistance would be slight. The first American troops landed on the Italian peninsula in September 1943, and Italy surrendered on 8 September. German troops in Italy were prepared, however, and took up the defensive positions. As winter approached, the Allies made slow progress against the heavily defended German Winter Line, until the victory at Monte Cassino. Rome fell to the Allies on 4 June 1944.

Strategic bombing

Numerous bombing runs were launched by the United States aimed at the industrial heart of Germany. Using the high altitude B-17, it was necessary for the raids to be conducted in daylight for the drops to be accurate. As adequate fighter escort was rarely available, the bombers would fly in tight, box formations, allowing each bomber to provide overlapping machine-gun fire for defense. The tight formations made it impossible to evade fire from Luftwaffe fighters, however, and American bomber crew losses were high. One such example was the Schweinfurt-Regensburg mission, which resulted in staggering loses of men and equipment. The introduction of the revered P-51 Mustang, which had enough fuel to make a round trip to Germany's heartland, helped to reduce losses later in the war.

Operation Overlord

The second European front that the Soviets had pressed for was finally opened on 6 June 1944, when the Allies attacked the heavily-fortified Atlantic Wall. Supreme Allied commander General Dwight D. Eisenhower had delayed the attack because of bad weather, but finally the largest amphibious assault in history began.

After prolonged bombing runs on the French coast by the U.S. Army Air Force, 225 U.S. Army Rangers scaled the cliffs at Pointe du Hoc under intense enemy fire and destroyed the German gun emplacements that could have threatened the amphibious landings.

Also prior to the main amphibious assault, the American 82nd and 101st Airborne divisions dropped behind the beaches into Nazi-occupied France, in an effort to protect the coming landings. Many of the paratroopers had not been dropped on their intended landing zones and were scattered throughout Normandy.

As the paratroops fought their way through the hedgerows, the main amphibious landings began. The Americans came ashore at the beaches codenamed 'Omaha' and 'Utah'. The landing craft bound for Utah, as with so many other units, went off course, coming ashore two kilometers off target. The 4th Infantry Division faced weak resistance during the landings and by the afternoon were linked up with paratroopers fighting their way towards the coast.

However, at Omaha the Germans had prepared the beaches with land mines, Czech hedgehogs and Belgian Gates in anticipation of the invasion. Intelligence prior to the landings had placed the less experienced German 714th Division in charge of the defense of the beach. However, the highly trained and experienced 352nd moved in days before the invasion. As a result, the soldiers from the 1st and 29th Infantry Divisions became pinned down by superior enemy fire immediately after leaving their landing craft. In some instances, entire landing craft full of men were mowed down by the well-positioned German defenses. As the casualties mounted, the soldiers formed impromptu units and advanced inland.

The small units then fought their way through the minefields that were in between the Nazi machine-gun bunkers. After squeezing through, they then attacked the bunkers from the rear, allowing more men to come safely ashore.

By the end of the day, the Americans suffered over 6,000 casualties, including killed and wounded.

Operation Cobra

After the amphibious assault, the Allied forces remained stalled in Normandy for some time, advancing much more slowly than expected with close-fought infantry battles in the dense hedgerows. However, with Operation Cobra, launched on 24 July with mostly American troops, the Allies succeeded in breaking the German lines and sweeping out into France with fast-moving armored divisions. This led to a major defeat for the Germans, with 400,000 soldiers trapped in the Falaise pocket, and the capture of Paris on 25 August.

Operation Market Garden

The next major Allied operation came on 17 September. Devised by British General Bernard Montgomery, its primary objective was the capture of several bridges in the Netherlands. Fresh off of their successes in Normandy, the Allies were optimistic that an attack on the Nazi-occupied Netherlands would force open a route across the Rhine and onto the North German Plain. Such an opening would allow Allied forces to break out northward and advance toward Denmark and, ultimately, Berlin.

The plan involved a daylight drop of the American 82nd and 101st Airborne Divisions. The 101st was to capture the bridges at Eindhoven, with the 82nd taking the bridges at Grave and Nijmegen. After the bridges had been captured, the ground force, also known as XXX Corps or "Garden", would drive up a single road and link up with the paratroops.

The operation failed because the Allies were unable to capture the bridge furthest to the north at Arnhem. There, the British 1st Airborne had been dropped to secure the bridges, but upon landing they discovered that a highly experienced German SS Panzer unit was garrisoning the town. The paratroopers were only lightly equipped in respect to anti-tank weaponry and quickly lost ground. Failure to quickly relieve those members of the 1st who had managed to seize the bridge at Arnhem on the part of the balance of the 6th, as well as the armored XXX Corps, meant that the Germans were able to stymie the entire operation. In the end, the operation's ambitious nature, the fickle state of war, and failures on the part of Allied intelligence (as well as tenacious German defense) can be blamed for Market-Garden's ultimate failure. This operation also signaled the last time that either the 82nd or 101st would make a combat jump during the war.

Battle of the Bulge

Unable to push north into the Netherlands, the Allies in western Europe were forced to consider other options to get into Germany. However, in December 1944, the Germans launched a massive attack westward in the Ardennes forest, hoping to punch a hole in the Allied lines and capture the Belgian city of Antwerp. The Allies responded slowly, allowing the German attack to create a large "bulge" in the Allied lines. In the initial stages of the offensive, American POW's from the 285th Field Artillery Observation Battalion were executed at the Malmedy massacre by Nazi SS and Fallschirmjäger.

As the Germans pushed westward, General Eisenhower ordered the 101st Airborne and elements of the U.S. 10th Armored Division into the road junction town of Bastogne to prepare a defense. The town quickly became cut off and surrounded. The winter weather slowed Allied air support, and the defenders were outnumbered and low on supplies. When given a request for their surrender from the Germans, General Anthony McAuliffe, acting commander of the 101st, replied, "Nuts!", contributing to the stubborn American defense.[14] On 19 December, General Patton told Eisenhower that he could have his army in Bastogne in 48 hours. Patton then turned his army, at the time on the front in Luxembourg, north to break through to Bastogne. Patton's armor pushed north, and by 26 December was in Bastogne, effectively ending the siege. By the time it was over, more American soldiers had served in the battle than in any engagement in American history.[15]

Race to Berlin

Following the defeat of the German army in the Ardennes, the Allies pushed back towards the Rhine and the heart of Germany. With the capture of the Ludendorff bridge at Remagen, the Allies crossed the Rhine in March 1945. The Americans then executed a pincer movement, setting up the Ninth Army north, and the First Army south. When the Allies closed the pincer, 300,000 Germans were captured in the Ruhr Pocket. The Americans then turned east, meeting up with the Soviets at the Elbe River in April. The Germans surrendered Berlin to the Soviets on 2 May 1945.

The war in Europe came to an official end on V-E Day, 8 May 1945.

Planned attacks on the United States

Other units and services

- Cactus Air Force

- Devil's Brigade (1st Special Service Force)

- Eagle Squadron

- Flying Tigers

- Merrill's Marauders

- Office of Strategic Services

- Tuskegee Airmen

Timeline

Pacific War

| Battle | Campaign | Date start | Date end | Victory |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Attack on Pearl Harbor | 7 December 1941 | 7 December 1941 | Japan | |

| United States declares war on Japan | 8 December 1941 | 15 August 1945 | ||

| Battle of Guam | 8 December 1941 | 8 December 1941 | Japan | |

| Battle of Wake Island | Pacific Ocean theater of World War II | 8 December 1941 | 23 December 1941 | Japan |

| Battle of the Philippines | South West Pacific | 8 December 1941 | 8 May 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Balikpapan | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 23 January 1942 | 24 January 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Ambon | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 30 January 1942 | 3 February 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Makassar Strait | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 4 February 1942 | 4 February 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Badung Strait | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 18 February 1942 | 19 February 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Timor | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 19 February 1942 | 10 February 1943 | Japan (tactical); Allies (strategic) |

| Battle of the Java Sea | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 27 February 1942 | 1 March 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Sunda Strait | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 28 February 1942 | 1 March 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Java | Netherlands East Indies campaign | 28 February 1942 | 12 March 1942 | Japan |

| Invasion of Tulagi | Solomon Islands campaign | 3 May 1942 | 4 May 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of the Coral Sea | New Guinea campaign | 4 May 1942 | 8 May 1942 | Japan (tactical); Allies (strategic) |

| Battle of Corregidor | 5 May 1942 | 6 May 1942 | Japan | |

| Battle of Midway | Pacific Theater of Operations | 4 June 1942 | 7 June 1942 | United States |

| Battle of the Aleutian Islands | Pacific Theater of Operations | 6 June 1942 | 15 August 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of Tulagi and Gavutu-Tanambogo | Guadalcanal campaign | 7 August 1942 | 9 August 1942 | Allies |

| Battle of Savo Island | Guadalcanal campaign | 8 August 1942 | 9 August 1942 | Japan |

| Makin Raid | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 17 August 1942 | 18 August 1942 | United States |

| Battle of the Tenaru | Guadalcanal campaign | 21 August 1942 | 21 August 1942 | Allies |

| Battle of the Eastern Solomons | Guadalcanal campaign | 24 August 1942 | 25 August 1942 | United States |

| Battle of Milne Bay | New Guinea campaign | 25 August 1942 | 5 September 1942 | Allies |

| Battle of Edson's Ridge | Guadalcanal campaign | 12 September 1942 | 14 September 1942 | United States |

| Second Battle of the Matanikau | Guadalcanal campaign | 23 September 1942 | 27 September 1942 | Japan |

| Third Battle of the Matanikau | Guadalcanal campaign | 7 October 1942 | 9 October 1942 | United States |

| Battle of Cape Esperance | Guadalcanal campaign | 11 October 1942 | 12 October 1942 | United States |

| Battle for Henderson Field | Guadalcanal campaign | 23 October 1942 | 26 October 1942 | United States |

| Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands | Guadalcanal campaign | 25 October 1942 | 27 October 1942 | Japan |

| Naval Battle of Guadalcanal | Guadalcanal campaign | 12 November 1942 | 15 November 1942 | United States |

| Battle of Buna-Gona | New Guinea campaign | 16 November 1942 | 22 January 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of Tassafaronga | Guadalcanal campaign | 29 November 1942 | 29 November 1942 | Japan |

| Battle of Rennell Island | Guadalcanal campaign | 29 January 1943 | 30 January 1943 | Japan |

| Battle of Wau | New Guinea campaign | 29 January 1943 | 31 January 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of the Bismarck Sea | New Guinea campaign | 2 March 1943 | 4 March 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of Blackett Strait | Solomon Islands campaign | 6 March 1943 | 6 March 1943 | United States |

| Battle of the Komandorski Islands | Aleutian Islands campaign | 27 March 1943 | 27 March 1943 | Inconclusive |

| Death of Isoroku Yamamoto | Solomon Islands campaign | 18 April 1943 | 18 April 1943 | United States |

| Salamaua-Lae campaign | New Guinea campaign | 22 April 1943 | 16 September 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of New Georgia | Solomon Islands campaign | 20 June 1943 | 25 August 1943 | Allies |

| Battle of Kula Gulf | Solomon Islands campaign | 6 July 1943 | 6 July 1943 | Inconclusive |

| Battle of Kolombangara | Solomon Islands campaign | 12 July 1943 | 13 July 1943 | Japan |

| Battle of Vella Gulf | Solomon Islands campaign | 6 August 1943 | 7 August 1943 | United States |

| Battle of Vella Lavella | Solomon Islands campaign | 15 August 1943 | 9 October 1943 | Allies |

| Bombing of Wewak | New Guinea campaign | 17 August 1943 | 17 August 1943 | United States |

| Finisterre Range campaign | New Guinea campaign | 19 September 1943 | 24 April 1944 | Allies |

| Naval Battle of Vella Lavella | Solomon Islands campaign | 7 October 1943 | 7 October 1943 | Japan |

| Battle of the Treasury Islands | Solomon Islands campaign | 25 October 1943 | 12 November 1943 | Allies |

| Raid on Choiseul | Solomon Islands campaign | 28 October 1943 | 3 November 1943 | Allies |

| Bombing of Rabaul | New Guinea campaign | 1 November 1943 | 11 November 1943 | Allies |

| Bougainville campaign | New Guinea campaign | 1 November 1943 | 21 August 1945 | Allies |

| Battle of Tarawa | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 20 November 1943 | 23 November 1943 | United States |

| Battle of Makin | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 20 November 1943 | 24 November 1943 | United States |

| Battle of Cape St. George | Solomon Islands campaign | 26 November 1943 | 26 November 1943 | United States |

| New Britain Campaign | New Guinea campaign | 15 December 1943 | 21 August 1945 | Allies |

| Landing at Saidor | New Guinea campaign | 2 January 1944 | 10 February 1944 | Allies |

| Battle of Cape St. George | Solomon Islands campaign | 29 January 1944 | 27 February 1944 | Allies |

| Battle of Kwajalein | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 31 January 1944 | 3 February 1944 | United States |

| Operation Hailstone | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 17 February 1944 | 18 February 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Eniwetok | Gilbert and Marshall Islands campaign | 17 February 1944 | 23 February 1944 | United States |

| Admiralty Islands campaign | New Guinea campaign | 29 February 1944 | 18 May 1944 | Allies |

| Landing on Emirau | New Guinea campaign | 20 March 1944 | 27 March 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Saipan | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 15 June 1944 | 9 July 1944 | United States |

| Battle of the Philippine Sea | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 19 June 1944 | 20 June 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Guam | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 21 July 1944 | 8 August 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Tinian | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 24 July 1944 | 1 August 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Peleliu | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 15 September 1944 | 25 November 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Angaur | Mariana and Palau Islands campaign | 17 September 1944 | 30 September 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Leyte | Philippines campaign (1944–45) | 20 October 1944 | 31 December 1944 | Allies |

| Battle of Leyte Gulf | Philippines campaign | 23 October 1944 | 26 October 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Ormoc Bay | Philippines campaign | 11 November 1944 | 21 December 1944 | United States |

| Battle of Mindoro | Philippines campaign | 13 December 1944 | 16 December 1944 | United States |

| Battle for the Recapture of Bataan | Philippines campaign | 31 January 1945 | 8 February 1945 | Allies |

| Battle of Manila (1945) | Philippines campaign | 3 February 1945 | 3 March 1945 | Allies |

| Battle for the Recapture of Corregidor | Philippines campaign | 16 February 1945 | 26 February 1945 | Allies |

| Battle of Iwo Jima | Volcano and Ryukyu Islands campaign | 19 February 1945 | 16 March 1945 | United States |

| Invasion of Palawan | Philippines campaign | 28 February 1945 | 22 April 1945 | United States |

| Battle of Okinawa | Volcano and Ryukyu Islands campaign | 1 April 1945 | 21 June 1945 | Allies |

| Operation Ten-Go | Volcano and Ryukyu Islands campaign | 7 April 1945 | 7 April 1945 | United States |

| Battle of Tarakan | Borneo campaign (1945) | 1 May 1945 | 19 June 1945 | Allies |

European Theater

| Battle | Campaign | Date start | Date end | Victor |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nazi Germany declares war on the U.S. | 11 December 1941 | |||

| Operation Torch | North African campaign | 8 November 1942 | 10 November 1942 | Allies |

| Run for Tunis | Tunisia campaign | 10 November 1942 | 25 December 1942 | Germany |

| Battle of Sidi Bou Zid | Tunisia campaign | 14 February 1943 | 17 February 1943 | Germany |

| Battle of the Kasserine Pass | Tunisia campaign | 19 February 1943 | 25 February 1943 | Germany |

| Battle of El Guettar | Tunisia campaign | 23 March 1943 | 7 April 1943 | United States |

| Allied invasion of Sicily | Italian campaign | 9 July 1943 | 17 August 1943 | Allies |

| Allied invasion of Italy | Italian campaign | 3 September 1943 | 16 September 1943 | Allies |

| Bernhardt Line | Italian campaign | 1 December 1943 | 15 January 1944 | Allies |

| Battle of Monte Cassino | Italian campaign | 17 January 1944 | 19 May 1944 | Allies |

| Operation Shingle | Italian campaign | 22 January 1944 | 5 June 1944 | Allies |

| Battle of Normandy | Western Front | 6 June 1944 | 25 August 1944 | Allies |

| Gothic Line | Italian campaign | 25 August 1944 | 17 December 1944 | Allies |

| Operation Market Garden | Western Front | 17 September 1944 | 25 September 1944 | Germany |

| Battle of Huertgen Forest | Western Front | 19 September 1944 | 10 February 1945 | United States |

| Battle of Aachen | Western Front | 1 October 1944 | 22 October 1944 | United States |

| Operation Queen | Western Front | 16 November 1944 | 16 December 1944 | Germany |

| Battle of the Bulge | Western Front | 16 December 1944 | 25 January 1945 | Allies |

| Operation Bodenplatte | Western Front | 1 January 1945 | 1 January 1945 | Allies |

| Colmar Pocket | Western Front | 20 January 1945 | 9 February 1945 | Allies |

| Spring 1945 offensive in Italy | Italian campaign | 6 April 1945 | 2 May 1945 | Allies |

See also

- List of Medal of Honor recipients for World War II

- Equipment losses in World War II

- Military history of the United States

- United States casualties of war

- World War II casualties

- Allied war crimes during World War II

- Greatest Generation

- United States home front during World War II

- American Minority Groups in World War II

References

- ^ http://www.wpunj.edu/irt/courses/hist365/declarewar.htm

- ^ "World War 2 Casualties". World War 2. Otherground, LLC and World-War-2.info. 2003. Retrieved 20 June 2006.

- ^ "American Merchant Marine in World War II" usmm.org

- ^ "Isolationism" USHistory.com

- ^ One War Won, TIME Magazine, December 13, 1943

- ^ "Lend Lease Act, 11 March 1941". history.navy.mil

- ^ Hakim, Joy (1995). A History of Us: War, Peace and all that Jazz. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 123–127. ISBN 0-19-509514-6.

{{cite book}}: Cite has empty unknown parameter:|coauthors=(help) - ^ Mae Mills Link and Hubert A. Coleman, Medical support of the Army Air Forces in World War II (1955) p 851

- ^ "Battle of Midway, 4-7 June 1942" history.navy.mil

- ^ "Pacific Theater, World War II — Island Hopping, 1942-1945", USHistory.com.

- ^ Wesley Frank Craven and James Lea Cate, The Army Air Forces In World War II: Vol 7: Services Around The World (1958) ch 10

- ^ "A Chronology of US Historical Documents". Oklahoma College of Law

- ^ "Command Failures: Lessons Learned from Lloyd R. Fredendall" Steven L. Ossad, findarticles.com

- ^ ""NUTS!" Revisited: An Interview with Lt. General Harry W. O. Kinnard". thedropzone.org

- ^ "Battle of the Bulge remembered 60 years later". defenselink.mil

Further reading

Air Force

- Perret, Geoffrey. Winged Victory: The Army Air Forces in World War II (1997)

Army

- Perret, Geoffrey. There's a War to Be Won: The United States Army in World War II (1997)

Europe

- Weigley, Russell. Eisenhower's Lieutenants: The Campaigns of France and Germany, 1944-45 (1990)

Marines

- Sherrod, Robert Lee. History of Marine Corps Aviation in World War II (1987)

Navy

- Morison, Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (2007)

Pacific

- Hornfischer, James D. (2011). Neptune's Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80670-0.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2006). Ship of Ghosts: The Story of the USS Houston, FDR's Legendary Lost Cruiser, and the Epic Saga of Her Survivors. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-80390-7.

- Hornfischer, James D. (2004). The Last Stand of the Tin Can Sailors: The Extraordinary World War II Story of the U.S. Navy's Finest Hour. Bantam Books. ISBN 978-0-553-38148-1.

- Parshall, Jonathan and Anthony Tully. Shattered Sword: The Untold Story of the Battle of Midway (2005).

- Spector, Ronald. Eagle Against the Sun: The American War With Japan (1985)

- Tillman, Barrett. Whirlwind: The Air War Against Japan, 1942-1945 (2010).

- Tillman, Barrett. Clash of the Carriers: The True Story of the Marianas Turkey Shoot of World War II (2005).

Biographies

- Ambrose, Stephen. The Supreme Commander: The War Years of Dwight D. Eisenhower (1999) excerpt and text search

- Beschloss, Michael R. The Conquerors: Roosevelt, Truman and the Destruction of Hitler's Germany, 1941-1945 (2002) excerpt and text search

- Buell, Thomas. The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond Spruance. (1974).

- Burns, James MacGregor. vol. 2: Roosevelt: Soldier of Freedom 1940-1945 (1970), A major interpretive scholarly biography, emphasis on politics online at ACLS e-books

- Larrabee, Eric. Commander in Chief: Franklin Delano Roosevelt, His Lieutenants, and Their War (2004), chapters on all the key American war leaders excerpt and text search

- James, D. Clayton. The Years of Macarthur 1941-1945 (1975), vol 2. of standard scholarly biography

- Leary, William ed. We Shall Return! MacArthur's Commanders and the Defeat of Japan, 1942-1945 (1988)

- Morison, Elting E. Turmoil and Tradition: A Study of the Life and Times of Henry L. Stimson (1960)

- Pogue, Forrest. George C. Marshall: Ordeal and Hope, 1939-1942 (1999); George C. Marshall: Organizer of Victory, 1943-1945 (1999); standard scholarly biography

- Potter, E. B. Bull Halsey (1985).

- Potter, E. B. Nimitz. (1976).

- Showalter, Dennis. Patton And Rommel: Men of War in the Twentieth Century (2006), by a leading scholar; excerpt and text search

- David J. Ulbrich (2011). Preparing for Victory: Thomas Holcomb and the Making of Modern Marine Corps, 1936-1943. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Institute Press. ISBN 1591149037.

External links

- World War II, from USHistory.com.

- A Chronology of US Historical Documents, Oklahoma College of Law.

- FAQ: D-Day and the Battle of Normandy, D-Day Museum.

- Omaha Beachhead, American Forces in Action Series.Washington D.C., United States Army Center of Military History 1994 (facsimile reprint of 1945). CMH Pub. 100-11.

- Lend-Lease Act, 11 March 1941, U.S. Congress. (from history.navy.mil)

- Cole, Hugh M.The Ardennes:Battle of the Bulge. United States Army in World War II Series. Washington, D.C.: Officed of the Chief of Military History, 1965.