Song Binbin

Song Binbin | |

|---|---|

| 宋彬彬 | |

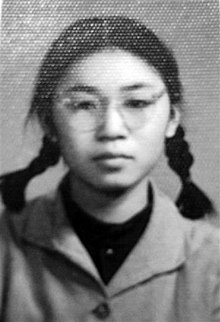

Song Binbin in the 1960s | |

| Born | 1949 (age 74–75) |

| Other names | Song Yaowu (Nickname) |

| Citizenship | United States |

| Known for | Student Red Guard leader during the Cultural Revolution, involvement with death of teacher Bian Zhongyun |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party |

| Movement | Cultural Revolution |

| Parent(s) | Song Renqiong (father) Zhong Yuelin (mother) |

| Song Binbin | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Simplified Chinese | 宋彬彬 | ||||||||

| |||||||||

Song Binbin (Chinese: 宋彬彬; born 1949), also known as Song Yaowu (Chinese: 宋要武), was a senior leader in the Chinese Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution. She is known for allegedly beating her deputy principal Bian Zhongyun to death with wooden sticks, along with other students.

Early life[edit]

Binbin was born in 1949[1] the daughter of Song Renqiong, one of China's founding leaders known as the Eight Immortals. In 1960, she started studying at the Experimental High School Attached to Beijing Normal University. In 1966, she was a senior leader among the leftist Red Guards at her girls’ school in Beijing. The Red Guard worked to overthrow China's institutional frameworks to demonstrate their devotion to Mao."[2]

Cultural Revolution[edit]

Binbin joined the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) in April 1966 as a reserve member. She led a rebellion at Experimental High School which was attached to Beijing Normal University, in Beijing, China. Newspapers reported she took part in the beating of the deputy principal, Bian Zhongyun, to death in August 1966 with a wooden stick, and seriously injuring vice-principal Hu Zhitao. That night, Song Binbin and others reported the cause of Bian Zhongyun's death to Wu De, the second secretary of the Beijing Municipal Committee of the CCP at the Beijing Hotel.[3] Bian was the first teacher killed in the Cultural Revolution, and her slaying led to further killings by the Red Guards, and eventually over one million of the Guards gathered in Tiananmen Square, where Binbin famously pinned a red band on Mao Zedong's arm. Her pen name Song Yaowu was also given by Mao at that time. The scene was captured in a famous photograph, causing the Red August. On August 20, 1966, Guangming Daily published an article signed by Binbin under her pen name "Song Yaowu", "I Put a Red Armband on Chairman Mao", which was reprinted by People's Daily newspaper the next day.[4]

At the end of August, Wang Renzhong met Liu Jin and Song Binbin at the Diaoyutai Guesthouse and mobilized them to go to Wuhan to protect the Hubei Provincial Committee of the CCP. Before Liu Jin went, Song Binbin and her classmates went to Wuhan in early September. Soon after, they wrote an article with the keynote of protecting the Hubei Provincial Party Committee of the CCP and handed it to the Provincial Party Committee. Immediately, the local newspaper published an open letter signed under pen name "Song Yaowu". The content was different from the original article by Song Binbin and others. The wording was stronger to protect the Hubei Provincial Committee of the CCP. Song Binbin was dissatisfied with this. She asked the person in charge of the provincial party committee and issued a statement through the provincial party committee stating that the open letter was not written by her, but she still did not agree to overthrow the provincial party committee.[5]

After returning to Beijing, Song Binbin became a member of the "Xiaoyao faction", and did not participate in the old Red Guard organizations. In April 1968, Song Binbin and her mother were taken to Shenyang under house arrest. In the early spring of 1969, Song Binbin escaped from Shenyang and came to the pastoral area of Xilingol League in Inner Mongolia Autonomous Region, and then joined the team. In the spring of 1972, at the recommendation of the local herdsmen and the brigade commune, Song Binbin was accepted by a university and then returned due to rumors. According to reports from fellow villagers and educated youths, the teacher in charge of enrollment in Xilingol League admitted Song Binbin under pressure, and Song Binbin entered Changchun Institute of Geology as a Worker-Peasant-Soldier student.[6]

In 1975, Song Binbin received a bachelor's degree from Changchun Institute of Geology.

Later life[edit]

After the Cultural Revolution, Binbin was admitted to the Graduate School of the Chinese Academy of Sciences as a graduate student, from 1978 to 1980. In 1980, Binbin went to the United States to study. She received a master's degree in geochemistry from Boston University in the United States in 1983. She completed a doctorate at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1989.[7]

After becoming naturalized as a U.S citizen, Binbin worked for the Massachusetts Department of Environmental Protection as an environmental analysis officer from 1989 to 2003. In 2003, she moved back to China, where she served as chairwoman of the British-owned Beijing Cobia System Engineering Co., Ltd. and Beijing Cobia Innovation Technology Development Co., Ltd.[8]

In September 2007, the Experimental High School Affiliated to Beijing Normal University (formerly the Women's Affiliated High School of Beijing Normal University) named Song Binbin as one of the 90 "honorary alumni" when celebrating the 90th anniversary of the school. This matter caused controversy when Wang Jingyao, husband of Bian Zhongyun, protested because he believed that Song Binbin was the main person in charge of the Red Guards in the school during the Cultural Revolution and thus responsible for the death of his wife.[9]

Controversy over the death of Bian Zhongyun[edit]

In 1995, Normal University High School for Girls 1968 alumni Wang Youqin published a text in Hong Kong, "1966: Students play the teacher's revolution", for the first time since August 5, 1966, where Youqin wrote that Binbin and other guards played a role in the death of Bian Zhongyun, are linked to form a causal relationship during those times.[10]

In 2003, Carma Hinton, a graduate of Beijing 101 Middle School, directed the Cultural Revolution documentary Morning Sun, which was not officially released in China, but was released in the United States. Song Binbin was interviewed, and for the first time publicly stated that during the Cultural Revolution, she had never participated in violent actions such as beating people, ransacking homes, or destroying the Four Olds. She claimed that The Guangming Daily signed her article without seeking her opinion in advance. Song Binbin denied that the article was written by her, nor did she authorize the reporter to ghostwrite.[11]

In 2004, Wang Youqin published another article "The Death of Bian Zhongyun", where she pointed out that Song Binbin was responsible for the Red Guard violence that led to Bian Zhongyun's death. The evidence was a list of seven people who had pledged to the hospital to rescue Bian Zhongyun at the Beijing Posts and Telecommunications University Hospital in Changping District, saying " Six of the seven are Red Guards students. The first name on the list is Song Binbin, a senior in the school and the head of the Red Guards.” Song Binbin responded to the claims in the article saying that the first name on the list of seven is Li Songwen, a teacher, while her name is ranked last, suggesting that she could not have played a major role in the death of Zhongyun.[12]

In 2002, a collection of publications related to sexology seminars, Chinese Femininities, Chinese Masculinities: A Reader, included research articles by American female scholar Emily Honig on the death of Bian Zhongyun. According to Wang Youqin's article, Honig claimed that Song Binbin was responsible for some of the violent activities in the early parts of Cultural Revolution.[13]

Apology[edit]

On January 12, 2014, at a meeting held at High School Attached to Beijing Normal University and was attended by more than 20 students and more than 30 teachers and family members of the alumni, she apologized for the actions of the Red Guards during the Cultural Revolution.[14]

The apology was met with mixed reactions in China: some people welcomed her words; some people said that these words came too late and are inadequate; others said that the CCP should apologize for the incidents that happened during those times.[15]

Cui Weiping, Beijing Film Academy professor and social critic, said in a telephone interview:[16]

Considering her identity, this is not enough. She is an important figure in the Red Guards, and the demands on her should be higher than ordinary people. She said she had witnessed a murder. It’s meaningless to say you witnessed a murder and then say you don’t know who the killers were.

Wang Youqin said in an interview that Song Binbin and various other Red Guards, in the past decade, have been actively denying persecution and involvement during the Cultural Revolution and mass killings during that time and believes that Song Binbin's responsibility in all the violence in the Women's Affiliated High School should be obvious, due to her position as one of the deputy directors of the school and organizer of the meetings by the school's revolutionary committee.[17]

In 2014, Bian's husband Wang Jingyao issued a statement accusing Song Binbin and others of covering up their evil deeds during the Cultural Revolution. He called their apologies hypocritical and he would not accept their apologies until the truth about their involvement in his wife's death was revealed to the world.[18]

References[edit]

- ^ Buckley, Chris (2014-01-13). "Bowed and Remorseful, Former Red Guard Recalls Teacher's Death". Sinosphere Blog. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "Song Binbin Offers New Apology for Death of Teacher During China's Cultural Revolution". Wall Street Journal. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ The Chinese Cultural Revolution; Remembering Mao's Victims 05/15/2007 Spiegel

- ^ "四十多年来我一直想说的话". China Studies Service Center (in Chinese (China)). The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "四十多年来我一直想说的话". China Studies Service Center (in Chinese (China)). The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "四十多年来我一直想说的话". China Studies Service Center (in Chinese (China)). The Chinese University of Hong Kong. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋彬彬:往日的辉煌与今日的眼泪" (in Chinese (China)). rfi.fr. 16 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ Buckley, Chris (2014-01-13). "Bowed and Remorseful, Former Red Guard Recalls Teacher's Death". Sinosphere Blog. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "毛澤東欽點紅衛兵 宋彬彬為文革道歉" (in Chinese (China)). storm.mg. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋彬彬为文革恶行道歉新动态:遗属声明斥"虚伪"" (in Chinese (China)). Voice of America. 30 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋任穷之女向文革中受伤害师生道歉 数度落泪" (in Chinese (China)). sohu.com. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋任穷之女向文革中受伤害师生道歉 数度落泪" (in Chinese (China)). sohu.com. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋任穷之女向文革中受伤害师生道歉 数度落泪" (in Chinese (China)). sohu.com. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "Song Binbin Offers New Apology for Death of Teacher During China's Cultural Revolution". Wall Street Journal. 13 January 2014. Retrieved 2023-02-25.

- ^ "宋彬彬为文革中校长被打致死道歉". 储百亮 (in Chinese (China)). The New York Times. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋彬彬:我的道歉和感谢" (in Chinese (China)). 21ccom. Archived from the original on 2016-03-05. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "宋彬彬为文革中校长被打致死道歉". 储百亮 (in Chinese (China)). The New York Times. 14 January 2014. Retrieved 2020-09-16.

- ^ "金鐘就宋彬彬對文革作出道歉訪問文革研究者王友琴" (in Chinese (China)). cnd.org. Retrieved 2020-09-16.