Shin-hanga

Shin-hanga (新版画, lit. "new prints", "new woodcut (block) prints") was an art movement in early 20th-century Japan, during the Taishō and Shōwa periods, that revitalized the traditional ukiyo-e art rooted in the Edo and Meiji periods (17th–19th century). It maintained the traditional ukiyo-e collaborative system (hanmoto system) where the artist, carver, printer, and publisher engaged in division of labor, as opposed to the parallel sōsaku-hanga (creative prints) movement.

The movement was initiated and nurtured by publisher Watanabe Shozaburo (1885–1962), and flourished from around 1915 to 1942, resuming on a smaller scale after the Second World War through the 1950s and 1960s. Watanabe approached European artists residing in Tokyo, Friedrich Capelari and Charles W. Bartlett to produce woodblock prints inspired by European Impressionism (which itself had drawn from ukiyo-e).

Shin-hanga artists incorporated Western elements such as the impression of light and the expression of individual moods. It eschewed ukiyo-e traditions of emulating hand-drawn brushstrokes seeking instead to "create works replete with creativity and rich with artistic quality, by avoiding enslavement to hand-drawn painting or old models".[1]

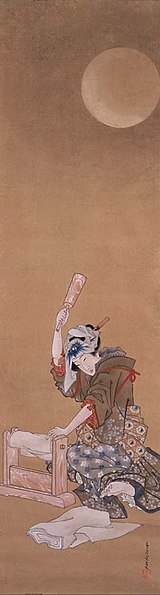

Watanabe introduced new printing techniques, most notably in the extensive use of printed layers of either baren suji-zuri (printed marks left deliberately by the baren) or goma-zuri (printed speckles), printed on thicker and usually less moist paper than past ukiyo-e prints. Watanabe considered shin-hanga to be fine art (geijutsu) and separate from shinsaku-hanga, the term that he used to describe less labor-intensive souvenir prints such as those by Takahashi Shōtei.[2] Shin-hanga themes, however, remained strictly traditional; themes of landscapes (fukeiga), famous places (meishō), beautiful women (bijinga), kabuki actors (yakusha-e), and birds-and-flowers (kachō-e).

History

[edit]Primarily aimed at foreign markets, shin-hanga prints appealed to Western taste for nostalgic and romanticized views of Japan and as such, enjoyed immense popularity overseas. In the 1920s, there were articles on shin-hanga in the International Studio, The Studio, The Art News and The Art Digest magazines. The first shin-hanga exported were Capelari and Bartlett prints in 1916, however, no foreign exhibitions were held until at Boston in March 1924. A larger exhibition of 68 works was held at the Herron Art Institute in October 1926. Later, the promoter of said Boston and Indianapolis touring exhibitions, artist Hiroshi Yoshida, helped organize and promote two very large exhibitions at the Toledo Museum of Art in Ohio in 1930 and 1936.[3] Through the 1930s and then after the Second World War, art dealers such as Robert O. Muller (1911-2003) imported shin-hanga to satisfy Western demand.

There was not much domestic market for shin-hanga prints in Japan. Ukiyo-e prints were considered by the Japanese as mass commercial products, as opposed to the European view of ukiyo-e as fine art during the climax of Japonisme. After decades of modernization and Westernization during the Meiji era, architecture, art and clothing in Japan came to follow Western modes. Japanese art students were trained in the Western tradition. Western oil paintings (yōga) were considered high art and received official recognition from the Bunten (The Ministry of Education Fine Arts Exhibition). Shin-hanga prints, on the other hand, were considered as a variation of the outdated ukiyo-e. They were dismissed by the Bunten and were subordinated under oil paintings and sculptures.[4]

As foreign demand for shin-hanga increased through the 1920s, the complexity of prints decreased. Ground layers of baren-suji and goma were less commonly seen and the overall number of printing impressions decreased. To satisfy foreign collectors, colors became brighter and more saturated. Shin-hanga supplanted shinsaku-hanga in the souvenir market and the latter ceased production.

Shin-hanga declined as the military government tightened its control over the arts and culture during wartime. In 1939, the Army Art Association was established under the patronage of the Army Information Section to promote war art. By 1943, an official commission for war painting was set up and artists’ materials were rationed. Overseas market for Japanese prints declined drastically at the same time.[5]

Demand for shin-hanga never regained its momentum postwar. Nevertheless a small number of artists continued in the tradition. Artists such as Itō Shinsui (1898–1972) and Shimura Tatsumi (1907–1980) continued to utilize the collaborative system during the 1960s and 1970s. In the last decades of the 20th century publishers instead concentrated on making reproductions of early 20th century shin-hanga; meanwhile sōsaku-hanga enjoyed immense popularity and prestige in the international art scene. The early 21st century has seen somewhat of a resurgence in shin-hanga popularity notably in market demand for earlier masters such as Kawase Hasui (1883–1957) and Hiroshi Yoshida (1876–1950), and for new artists continuing the shin-hanga aesthetic such as Paul Binnie (1967–).[6]

Steve Jobs, the head of Apple, was among the prominent collectors of shin-hanga.[7]

Shinsaku Hanga vs. Shin-hanga

[edit]Shinsaku-hanga (新作版画, lit. "newly-made prints", "newly made, not ukiyo-e reproductions") and shin-hanga have often been conflated. Shinsaku-hanga was the forerunner to shin-hanga and similarly created by the publisher Watanabe Shozaburo. It began in 1907 with the prints of Takahashi Shōtei and prospered until about 1927, with its popularity waning inversely to the growing popularity of shin-hanga. It had ceased completely by 1935.[8]

Shinsaku-hanga was essentially modernization of ukiyo-e and especially the prints of Hiroshige. Compared to shin-hanga, it did not depict contemporary Japan, instead it offered nostalgic views of pre-industrial, pre-Meiji Japan with modern printmaking techniques. Techniques characterized by continuing to replicate the hand-drawn brushstrokes of ukiyo-e (shin-hanga expressly resisted replicating brushstrokes) while beginning to eschew contour lines and large flat areas of color typical of historical ukiyo-e.[9]

This style was very popular early on with tourists in Japan (Watanabe described them as "souvenir prints") and for foreign export. Its typically smaller prints (smaller than shin-hanga) were less expensive to produce and less expensive to purchase, and they ultimately provided the financial stability to Watanabe to nurture the shin-hanga movement.

The best known shinsaku-hanga artists were Takahashi Shōtei, Ohara Koson, Ito Sozan and Narazaki Eisho. Each of these artists later moved to shin-hanga.

Notable artists

[edit]- Arai Yoshimune

- Hashiguchi Goyō

- Hirano Hakuhō

- Itō Shinsui

- Ito Yuhan

- Kaburagi Kiyokata

- Kawase Hasui

- Elizabeth Keith

- Kitano Tsunetomi

- Kobayakawa Kiyoshi

- Natori Shunsen

- Ohara Koson

- Koichi Okada

- Ota Masamitsu (also known as Ota Gako)

- Settai Komura

- Tatsumi Shimura

- Shiro Kasamatsu

- Takahashi Shōtei (also known as Hiroaki)

- Takeji Asano

- Torii Kotondo

- Tsuchiya Koitsu

- Tsuchiya Rakusan

- Yamakawa Shūhō

- Yamamura Toyonari

- Yoshida Hiroshi

References

[edit]- ^ Watanabe, Shozaburo Shin-hanga o tsukuru ni tsuite no watashi no iken [My opinions about how to make shin-hanga]

- ^ Shimizu, Hisao The Publisher Watanabe Shozaburo and the Birth of Shin-Hanga

- ^ Stephens, Amy Reigle (1993). The New wave : twentieth-century Japanese prints from the Robert O. Muller collection. ISBN 1870076192.

- ^ Brown, K. and Goodall-Cristante, H.

- ^ Brown, K. and Goodall-Cristante, H.

- ^ Brown, K. and Goodall-Cristante, H.

- ^ "Behind the Simplicity – Steve Jobs and Shin-Hanga". NHK. 2 January 2021.

- ^ Shimizu, Hisao The Publisher Watanabe Shozaburo and the Birth of Shin-Hanga in Brown, K. p29

- ^ Shimizu, Hisao The Publisher Watanabe Shozaburo and the Birth of Shin-Hanga in Brown, K. p23

Further reading

[edit]- Blair, Dorothy. Modern Japanese prints: printed from a photographic reproduction of two exhibition catalogues of modern Japanese prints published by the Toledo Museum of Art in 1930–1936. Ohio: Toledo Museum of Art, 1997.

- Brown, K. and Goodall-Cristante, H. Shin-Hanga: New Prints in Modern Japan. Los Angeles County Museum of Art, 1996. ISBN 0-295-97517-2

- Hamanoka, Shinji. Female Image: 20th Century Prints of Japanese Beauties. Hotei Publishing 2000. ISBN 90-74822-20-7

- Jenkins, D. Images of a Changing World: Japanese Prints of the Twentieth Century. Portland: Portland Art Museum, 1983. ISBN 0-295-96137-6

- Menzies, Jackie. Modern boy, Modern Girl: Modernity in Japanese Art 1910–1935. Sydney, Australia: Art Gallery NSW, c. 1998. ISBN 0-7313-8900-X

- Merritt, Helen and Nanako Yamada. (1995). Guide to Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints, 1900–1975. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 9780824817329; ISBN 9780824812867; OCLC 247995392

- Merritt, Helen. Modern Japanese Woodblock Prints: The Early Years. Honolulu: University of Hawaii Press 1990. ISBN 0-8248-1200-X

- Milone, Marco. La xilografia giapponese moderno-contemporanea, Edizioni Clandestine, 2023, ISBN 88-6596-746-3

- Mirviss, Joan B. Printed to Perfection: Twentieth-century Japanese Prints from the Robert O. Muller Collection. Washington D.C.: Arthur M. Sackler Gallery, Smithsonian Institution and Hotei Publishing 2004. ISBN 90-74822-73-8

- Newland, Amy Reigle. (2005). Hotei Encyclopedia of Japanese Woodblock Prints. Amsterdam: Hotei. ISBN 9789074822657; OCLC 61666175

- Smith, Lawrence. Modern Japanese Prints 1912–1989. New York, London, Paris: Cross River Press, 1994.

- Swinton, Elizabeth de Sabato. Terrific Tokyo: A panorama in Prints from the 1860s to the 1930s. Worcester: Worcester Art Museum, 1998. ISBN 0-936042-00-1

- Masuda, Koh. Kenkyusha's New Japanese-English Dictionary, Kenkyusha Limited, Tokyo 1991, ISBN 4-7674-2015-6

- Shimizu, Hisao The Publisher Watanabe Shozaburo and the Birth of Shin-Hanga in Water and Shadow: Kawase Hasui and Japanese Landscape Prints edited by Kendall Brown, Hotei Publishing, 2014. ISBN 9789004284654

- Watanabe, Shozaburo Shin-hanga o tsukuru ni tsuite no watashi no iken [My opinions about how to make shin-hanga] in Bijutsu gaho vol 44 no 8 (August 1921).

External links

[edit]- Video showing the printing of a shin-hanga work by craftsman David Bull (16 mins)

- "The Shin Hanga Movement in America" Video lecture by Dr. Kendall Brown on roles played by artist Hiroshi Yoshida and museum professional J. Arthur MacLean in disseminating the art (50 mins)

- Shin hanga — Viewing Japanese Prints website by John Fiorillo

- Dream Worlds: Modern Japanese Prints and Paintings from the Robert O. Muller Collection Online Exhibition

- Robert O. Muller Information about the man behind one of the most well known collections of Shin Hanga.