Sarah Margru Kinson

Sarah Margru Kinson | |

|---|---|

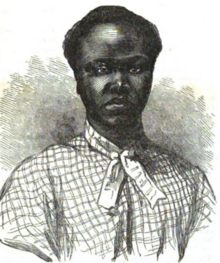

Sarah Margru Kinson, from an 1850 publication | |

| Born | Margru or Mar'gru about 1832 Mende country, West Africa |

| Died | after 1854 |

| Occupation | Educator |

Sarah Margru Kinson (about 1832 – after 1854) was a West African educator. As Margru or Mar'gru, she was one of the four children on La Amistad. As Sarah Kinson, she was educated at Oberlin College and returned to West Africa to be a missionary teacher. She is considered the first woman born in Africa to be educated in an American college.[1][2]

Early life and the Amistad[edit]

Margru was born in the Mende country of West Africa, in what is now called Sierra Leone.[3] She was sold to traders as a young girl, forced to walk to the coast, and shipped to Cuba aboard a Portuguese slave ship, the Tecora. In 1839, she was one of the four children aboard La Amistad, commandeered by Joseph Cinqué, a fellow Mendian, hoping to escape back to Africa. Instead, the Amistad was brought to shore by the United States Coast Guard at New London, Connecticut.[4] Margru and the others aboard were held in a jail in New Haven, exhibited and studied, while their legal status was determined in the courts. Abolitionist Lewis Tappan arranged for Margru and the other children to be moved to the residence of the white jailer and his wife, where she was a domestic servant.[5][6]

In 1841, when the Amistad passengers won their case and freedom, she went to stay with the rest in Farmington, Connecticut, where she was given the English name "Sarah Kinson". The group were still a matter of public curiosity, and gave presentations in various American cities about their experiences. In their public appearances, Kinson was known for reciting from Psalms, especially on themes of escape and redemption.[1] They returned to West Africa together, arriving near Freetown in January 1842, along with several American missionaries.[5]

Education[edit]

Kinson was still a child when the Amistad contingent arrived in West Africa in 1842. She lived at the Kaw Mendi (Komende) mission, learned to read and write, converted to Christianity, and worked for the American missionaries.[7] Under Lewis Tappan's ongoing interest in her care, she returned to the United States in 1846, and attend Oberlin's Little Red Schoolhouse, and then the Oberlin Collegiate Institute, both in Ohio.[8] At Oberlin, she roomed with an African-American girl, Lucy Stanton,[9] and learned to play accordion along with her academic studies.[5]

During this period of her time in the United States, Kinson was examined by Orson Squire Fowler, a phrenologist in New York City, who declared her to have a "vigorous constitution" in his published paper about her.[10][11]

Career[edit]

In 1849, Kinson returned to West Africa, this time to become head teacher of the new girls' school at the Sherbro Island mission.[12] She set up a sewing society for local women, to produce Western-style clothing.[1] Kinson married fellow African missionary teacher Edward Henry Green in 1852. They moved inland to start their own mission station in 1855, but her husband was dismissed from mission work soon after; beyond that time, her life was not recorded in mission reports or correspondence.[5]

Legacy[edit]

The schoolhouse Kinson attended in Ohio still stands, under the care of the Oberlin Heritage Center, and is open for tours.[13] Historians and other scholars have studied Kinson's life in recent years,[14] with more interest spurred after the film Amistad (1997).[1] Kimberly Jones sang the part of Margru in the 1997 opera Amistad by Anthony Davis and Thulani Davis, when it was first produced by the Lyric Opera of Chicago.[15] In 2004, artist Carolyn Evans portrayed Margru in a library program for Black History Month in White Plains, New York.[16] A 2013 children's book, Africa is My Home: A Child of the Amistad by Monica Edinger, uses "Magulu" as her original name, a variation of the name used in most sources.[17]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Royster, Jacqueline Jones. "Sarah's Story: Making a Place for Historical Ethnography in Rhetorical Studies" in C. Jan Swearingen, David S. Kaufer, eds., Rhetoric, the Polis, and the Global Village: Selected Papers from the 1998 Thirtieth Anniversary Rhetorical Society of America Conference (Routledge 1999): 39-51. ISBN 9781135667894

- ^ Lamphier, Peg A.; Welch, Rosanne (2017-01-23). Women in American History [4 volumes]: A Social, Political, and Cultural Encyclopedia and Document Collection [4 volumes]. Bloomsbury Publishing USA. p. 102. ISBN 978-1-61069-603-6.

- ^ Lawrance, Benjamin Nicholas (2015-01-28). Amistad's Orphans: An Atlantic Story of Children, Slavery, and Smuggling. Yale University Press. p. 74. ISBN 978-0-300-21043-9.

- ^ King, Wilma (2011-06-29). Stolen Childhood, Second Edition: Slave Youth in Nineteenth-Century America. Indiana University Press. p. 232. ISBN 978-0-253-22264-0.

- ^ a b c d Merrill, Marlene D. "Sarah Margru Kinson: The Two Worlds of an Amistad Captive" (a 2003 booklet made for the Oberlin Historical and Improvement Organization).

- ^ "Sarah Margru Kinson, Child of the Amistad". Ohio Memory (July 6, 2018). Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ "Appeal for Funds for the Mendi Mission". New-York Tribune. 1843-01-31. p. 3. Retrieved 2023-10-02 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Lubet, Steven (2015-08-27). The 'Colored Hero' of Harper's Ferry: John Anthony Copeland and the War against Slavery. Cambridge University Press. pp. 49–50. ISBN 978-1-316-35220-5.

- ^ Evans, Stephanie Y. (2016-12-01). Black Women in the Ivory Tower, 1850-1954: An Intellectual History. University Press of Florida. ISBN 978-0-8130-6305-8.

- ^ Branson, Susan (2022-01-15). Scientific Americans: Invention, Technology, and National Identity. Cornell University Press. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-5017-6092-1.

- ^ "Miscellany". The American Phrenological Journal and Miscellany. 12 (6): 230–231. June 1850.

- ^ Browne-Marshall, Gloria J. (2021-01-01). She Took Justice: The Black Woman, Law, and Power – 1619 to 1969. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-000-28355-6.

- ^ "House of History". Pulse Lorain Magazine. Retrieved 2023-10-01.

- ^ Lawson, Ellen NicKenzie; Merrill, Marlene (1984). The Three Sarahs: Documents of Antebellum Black College Women. E. Mellen Press. ISBN 978-0-88946-536-7.

- ^ Page, Tim (1997-12-01). "'Amistad' Misses the Boat". Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ^ Crowe, Alice (2004-02-09). "Slave Girl's Story; Artist Portrays Margru, a Child Prisoner on Amistad". The Journal News. p. 9. Retrieved 2023-10-02 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Edinger, Monica (2013). Africa Is My Home: A Child of the Amistad. Candlewick Press. ISBN 978-0-7636-5038-4.