Riley & Cowley

An 1887 company advertisement | |

| Company type | Private |

|---|---|

| Industry | Engineering |

| Founded | 1869 |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | 1905 |

| Fate | Dissolved |

| Successor | The Riley Machine Works |

| Headquarters | Brooklyn, New York , United States |

| Products |

|

| Services | Engine and boiler repairs |

Number of employees |

|

Riley & Cowley was an American marine engineering firm established in 1869 in Brooklyn, New York. The company specialized in the design and manufacture of marine steam engines for small watercraft such as steam yachts, launches and tugboats, and was particularly noted for its light and compact, high-performance, compound and triple expansion engines. The company also produced screw propellers, dredging machinery and other marine equipment.

By the 1880s, the company was building engines for the pleasure craft of some of New York's wealthiest men, such as R. V. Pierce and Pierre Lorillard III, and by 1890 it was producing some of the smallest triple-expansion engines then built in the United States. In 1902, the company also built a steam car. The company was dissolved in 1905 following the death of one of its founders.

Company history[edit]

Establishment[edit]

Reuben Riley was an assistant engineer with the United States Navy during the American Civil War.[1] After receiving his discharge in 1865,[1] Riley returned to New York where, together with engineer Robert Cowley and George Besser, he established a machine shop at 3 Summit Street, Brooklyn, which traded under the name Riley, Cowley & Besser.[2][3] This partnership was dissolved in October 1868 with the departure of Besser,[4] but Riley and Cowley retained their business association.

In 1869, the two remaining partners established a new machine shop in Brooklyn with the company name Riley & Cowley.[5] Prior to 1879, the company was located at 187 Van Brunt Street, on the corner of Van Brunt and Bowne Streets. Riley and Cowley eventually acquired a property on the corner of Richards and Bowne Streets, Brooklyn, and in 1879, plans were announced for the construction on this site of "two one and two-story brick shops, 40x60 and 100 [ft], tin roof and wooden and brick cornice".[6] After the relocation of the company to this address, these buildings appear to have been utilized as "a machine shop, blacksmith shop, pattern shop ... and storehouse."[7] The company would remain at this address for the balance of its 36-year history.[7]

Activities[edit]

Riley & Cowley specialized in the design and manufacture of compound and triple expansion steam propeller engines for small watercraft such as yachts, launches and tow boats. They also designed and built single-cylinder marine engines, marine propellers and machinery for steam dredges, as well as making engine and boiler repairs. Riley & Cowley engines had a reputation for speed, reliability, economy, compactness, lightness and ease of maintenance.[8] In particular, the company's attention to balancing all parts of an engine to reduce or eliminate vibration resulted in engines capable of achieving optimal performance.[8] Some engines were sufficiently self-contained and light in weight that they could be readily removed from the hull for winter storage.[8][9]

Engines built by the company were distributed to "all parts of the United States".[5] The company employed 55 people by the mid-1880s,[10] about half of whom were machinists;[5] the number of employees had risen to 100 by 1902, about forty of whom were machinists.[11]

By the 1880s, Riley & Cowley were supplying engines to members of New York's elite yachting set. Clients of the company included leading political and business identities such as Brooklyn mayor James Howell,[12] patent medicine manufacturer Ray Vaughn Pierce,[13] heir to the Aspinwall fortune, the Rev. John A. Aspinwall,[12] and others.[a]

In 1890, the company supplied what was then reportedly the smallest triple-expansion engine built in the United States—with cylinders of 4, 6.5 and 10 inches (10, 17 and 25 cm) by 8-inch (20 cm) stroke—for Aspinwall's steam launch Secret.[14] An engine of similar pattern was also installed in the steam launch Lillian, a vessel built for tobacco heir Pierre Lorillard III for use as a hunting launch along the East Coast.[15] These 75 hp (56 kW), 450 rpm triple expansion engines operated at a steam pressure of about 250 psi (1,700 kPa) and were characterized by "simplicity of construction and accessibility of parts", making them "peculiarly adapted" to their purpose.[15][9] The engines also featured a simple reversing mechanism that dispensed with the usual linkages.[15][9] This model of small triple-expansion powerplant seems to have been particularly successful for the company, the type eventually finding its way into "many steam launches and yachts where it has given excellent satisfaction".[9] The company would later build even smaller triple-expansion engines.[16]

An unusual watercraft to receive a Riley & Cowley engine in 1890 was an "unsinkable" 58-foot (18 m) steam yawl which the inventor, Captain Frank Norton, planned to take across the Atlantic as proof of concept. The engine supplied for this vessel was a 30 hp (22 kW) compound type with cylinders of 5.5 and 10 inches (14 and 25 cm), an operating pressure of 120 psi (830 kPa) and coal consumption of about 1/2 ton per day.[17]

In 1891, Riley & Cowley completed the engine for a fast steam launch for the Yale College Boat Club. The launch, intended to keep pace with rowing regattas, had a speed requirement of 14 miles per hour (23 km/h), but several other companies had tried and failed to meet the requirement. Riley & Cowley supplied a triple expansion engine with cylinders of 5, 8 and 13.5 inches (13, 20 and 34 cm) with 8-inch (20 cm) stroke, which in trials handily exceeded the requirement by recording a speed of 16.5 mph (26.6 km/h).[18]

Around the same time, a fast steam launch, named Norwood, was completed for Norman L. Munro at the yard of C. D. Mosher. Mosher built both the launch and its engine, but the latter failed to produce adequate performance until overhauled by Riley & Cowley.[19] After the overhaul, Norwood broke the record between New York Harbor and Sandy Hook in a race with the fast steamer Monmouth, covering the 14-mile (23 km) distance in 32 minutes or better than 26 mph (42 km/h; 23 kn), thus laying claim to being not only the fastest vessel in New York Harbor,[19] but the fastest steam launch in the world, rivalling that of some naval torpedo boats of the day.[20] Her top speed was said to be in excess of 30 miles per hour (48 km/h; 26 kn).[21]

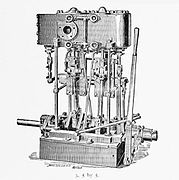

Marine engine gallery[edit]

-

3 and 5 by 5 in (7.6 and 12.7 by 12.7 cm) compound

-

4.5 and 9 by 6 in (11 and 23 by 15 cm) compound

-

4, 6.5 and 10 by 8 in (10, 17 and 25 by 20 cm) triple expansion

-

5, 8 and 13.5 by 8 in (13, 20 and 34 by 20 cm) triple expansion

Steam car[edit]

In 1902, Riley & Cowley built a steam car to the order of one B. M. Whitlock,[b] in the style of "a high powered, foreign gasoline touring car".[23] The vehicle, which seated two people, had a wheelbase of 8 feet 6 inches (2.59 m) and weighed about 4,000 lb (1,800 kg) in all, "including supplies".[23] The vehicle had two gears—which operated in both forward and reverse, as the engine was run in reverse to reverse the vehicle.[23] The driver steered by means of a 16-inch (41 cm) wheel on an inclined column.[23] Two brakes were provided—a steam and a foot brake.[23]

The powerplant, a compound steam engine with cylinder bores of 3 and 6 inches (7.6 and 15.2 cm) and a stroke of 6 inches (15 cm), was capable of developing 12 bhp (8.9 kW) at 150 psi (1,000 kPa) or 15 bhp (11 kW) at 300 psi (2,100 kPa); side-chain drive was used to transmit power to the wheels. The boiler, a fire-tube type 18 inches (46 cm) in height, was placed at the front of the vehicle, concealed beneath an aluminium bonnet. A fuel tank with a capacity of 25 US gallons (95 L; 21 imp gal) was located at the extreme rear, while the water tank, with a capacity of 100 US gallons (380 L; 83 imp gal), was fitted in the body. "Ingenious" exhaust pipes carried the exhaust gases to the rear of the vehicle.[23] Suspension of the vehicle was by leaf springs. The wheels were fitted with 32-by-2.5-inch (81.3 cm × 6.4 cm) hardened fabric tyres, which could be inflated by means of an inbuilt air pump.[23] This vehicle appears to have been the only steam car ever built by the company.[24]

Closure[edit]

Following the death of Robert Cowley, senior partner in the firm, in January 1905, the company was wound up.[25] In June, the entire equipment of the company, including patterns for engines, propellers, gears, pumps and other machinery, was offered for private sale.[26]

A few weeks later, in July, the surviving partner, Reuben Riley, established a new business at 192 24th Street, Brooklyn, The Riley Machine Works, capitalized at $6,500 (equivalent to $220,422 in 2023).[27] Incorporators of the new firm were Riley, his wife Amanda and son Frank, with Riley serving as company president and Frank as vice-president and general manager. The firm offered "special attention to marine repairs". This company appears to have been dissolved around the time of the death of Riley's wife in May 1908.[c]

About the proprietors[edit]

Reuben Riley was born in Tuckahoe, Westchester County, New York, on October 25, 1838. He received a "good public school education"[1] before travelling to New York in 1854, where he completed a five-year apprenticeship as a machinist and engineer with Henry Esler & Co. of South Brooklyn. During the American Civil War, Riley joined the United States Navy, serving from 1863 to the end of the war aboard USS Honeysuckle, during which time he was promoted from Assistant Engineer to 2nd Assistant Engineer. Discharged from the Navy on August 21, 1865, he returned to New York to co-found the firm of Riley & Cowley.[1]

Riley married Amanda Hilliker of Tuckahoe, New York in 1860. The couple had four children, including Frank M. Riley, who followed his father into the family business. Riley was a Freemason, an Aid-de-Camp to the Commander in Chief, Grand Army of the Republic, and a member of the board of trustees of the Brooklyn Bridge.[1] A respected engineer, he is known to have given a number of well-received lectures in the field.[d] He became wealthy as a result of his business activities.[30]

Robert Cowley, an engineer, was born in Stockton-on-Tees, England, on January 19, 1836, and emigrated to North America as a young man. He married a Canadian-born woman, Annie Ramsay, in Toronto, Canada, on January 3, 1860. The couple had two children together, Charles Ramsey, who followed his father into the family business, and a daughter Ida, later Mrs. Ida L. Knapp.[31]

In addition to his work with Riley & Cowley, Cowley was a director of the Hamilton Bank. He was a devout Christian and a board member of the First Place Methodist Church of Brooklyn, which he attended three times a week—for prayer meetings every Wednesday and twice on Sundays. He was also a keen art collector, accumulating a substantial gallery of works through the course of his life, including "many ... by the old masters."[31] Cowley died suddenly on January 12, 1905, at the age of 68. He was survived by his wife and children.[31]

Production table[edit]

The following table represents only a sample of engines built by the company, for some of the more notable watercraft.

| Watercraft | Engine | Notes; references | ||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Name[e] | Type[f] | Yr. [g] |

Len. [h] |

Designer | Builder | Original owner | Original homeport[i] |

Type[j] | Cyl. (ins)[k] |

Str. (ins)[l] |

| |

| Port Chester | Freight steamer | 1879 | 100.0 | Lawrence & Foulks | Ferris & Studwell | Port Chester, NY | LP | 20 | 22 | [32] | ||

|

Steam yacht | 1886 | 37.6 | Dr. S. Church | J. G. Purdy | Dr. Stuart Church[n] | Brooklyn | C | 4, 7.75 | 6 | [33][34] | |

|

Steam yacht | 1887 | 40.0 | A. L. Riker | J. Lennox | W. J. Riker | New York, NY | C | 4.5, 8 | 6 | [35][36] | |

| Nomad | Steam yacht | 1887 | 74.0 | Jacob Lorillard | Samuel H. Pine | Adrian Iselin, Jr[o] | New York, NY | TE | 6.5, 10, 16 | 10 | [37][38] | |

| Orrmoore | Steam yacht | 1887 | 67.0 | Dr. Stuart Church | Samuel Ayers | A. E. Orr | New York NY | C | 6, 9 | 6 | 28 | [39][40] |

| Dandy | Steam yacht | ~1888 | 57.0 | Frank Boyer | New York, NY | TE | 4, 6, 10 | 8 | [41][42] | |||

| Frolic | Steam yacht | 1889 | 50.0 | Samuel Ayers | Samuel Ayers | Robert Mayfield | TE | 4.5, 6.5, 10 | 8 | [43][44] | ||

| Cygnet | Steam launch | ~1889 | 47.0 | Dr. Stuart Church | Brooklyn, NY | C | [45] | |||||

| Crescent | Steam launch | ~1889 | O. S. Presbrey | Port Henry, NY | C | [45] | ||||||

| Secret | Steam yacht | 1889 | 58.0 | Samuel Ayers | Samuel Ayers | J. A. Aspinwall | TE | 4, 6, 10 | 8.5 | [14][46] | ||

| Steam yawl | 1890 | 58.0 | Frank Norton | Frank Norton | C | 5.5, 10 | 30 | Experimental "unsinkable" boat built for transatlantic voyage[17] | ||||

| Steam launch | 1890 | 65.0 | Jonson Iron Works | Pierre Lorillard III | TE | 4, 6.5, 10 | 8 | 75 | [47] Designed for hunting expeditions on the rivers of Florida.[15] | |||

|

Steam yacht | 1890 | 37.0 | Seabury & Co. | Seabury & Co. | W. Fred Lawrence | C | 4.5, 9 | 8 | [48][49] | ||

| Steam yacht | 1890 | 122.5 | Henry J. Gielow | H. C. Wintringham | R. V. Pierce | Buffalo, NY | FA/C/I | 11, 22 | 15 | [13][50] | ||

| Steam launch | 1891 | 53.0 | Samuel Ayers | Yale College Boat Club | TE | 5, 8, 13.5 | 8 | Fast launch designed to keep pace with rowboat races[18][51][52] | ||||

| Vulcan | Steam yacht | 1891 | 72.0 | J. B. Baugh | J. B. Baugh | J. B. Baugh[p] | TE | 6, 10, 16 | 10 | "[F]or use on the [Great] lakes".[12] | ||

| Steam launch | 1892 | Gas Engine & Power Co. | City Dock Dept. (NY) | New York, NY | [54] | |||||||

| Steam launch | 1892 | 40.0 | C. TenEycke | C | 4.5, 9 | 6 | "[F]or carrying passengers from the railroad depot to the hotel" (on Greenwood Lake).[12] | |||||

| Steam launch | 1892 | 52.0 | B. McCarrick | James Howell | TE | 4, 6, 10 | 8 | "[T]o be used on Lake Champlain as a pleasure boat".[12] | ||||

| Espadon | Steam launch | 1892 | 35.0 | A. Carey Smith | Seabury & Co. | FA/C | 3, 6 | 5 | [55] | |||

| Kanaka | Steam yacht | 1892 | 52.0 | Roberts Safety Water Tube Co. | Roberts Safety Water Tube Co. | C | 4.5, 9 | 6 | [56] | |||

| Steam yacht | 1894 | 84.0 | Gas Engine & Power Co. | Gas Engine & Power Co. | TE | 6.5, 10, 16 | 10 | [57] | ||||

| Steam yacht | 1896 | 85.0 | Henry J. Gielow | J. F. Hawkins | Benjamin M. Whitlock | C | 7, 14 | 9 | [58][59][60] | |||

|

Steam yacht | 1900 | 109.0 | Hiram Wellers & Sons | Hiram Wellers & Sons | TE | 6.5, 10, 16 | 10 | Twin-screw steamer with two engines[61][62] | |||

|

Yacht tender | 1903 | 27.5 | Wintringham | Henry J. Gielow | TE | 3, 5, 8 | 5 | [16] | |||

| Gadabout | Steam launch | 1904 | 43.5 | E. B. Schock | E. M. Fulton | E. M. Fulton | C | 4, 8 | 6 | [63] | ||

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ See production table.

- ^ Probably the New York yachting uniform manufacturer.[22]

- ^ Judging by the company's advertising history; the company advertised regularly until August 1908 when advertising ceases and is not renewed.

- ^ Examples:[28][29]

- ^ Name of vessel. When a vessel had more than one name in the course of its career, the names are listed chronologically in descending order.

- ^ Type of watercraft. All vessels in the table were screw-propelled.

- ^ Year built.

- ^ Length in feet.

- ^ So far as can be determined.

- ^ Type of engine. Abbreviations as follows: LP = low pressure; C = compound; TE = triple expansion; FA = fore-and-aft; I = inverted. Note that while only one of the engines listed in this table is documented as inverted, all the engines listed were likely inverted since by this time screw engines of the inverted type had become the standard pattern and the "inverted" descriptor was therefore considered superfluous.

- ^ Cylinder (bore) size in inches.

- ^ Stroke in inches.

- ^ Indicated horsepower.

- ^ Owner's given name spelled "Stewart" in some sources.

- ^ Son of New York financier Adrian Georg Iselin.

- ^ The source gives the owner's name as "J. I. Baught";[12] presumably this is a transcription error as Manning's Yacht Register lists the designer/builder as "J. B. Baugh".[53]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e Whittemore 1889. pp. 301–2.

- ^ Lain 1868. p. 521.

- ^ Stiles 1884. p. 691.

- ^ "Special Notices". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1868-10-14. p. 3.

- ^ a b c Half-Century's Progress of the City of Brooklyn. p. 202.

- ^ "Buildings Projected. Brooklyn, N. Y. Plan 685". Real Estate Record and Builders' Guide. XXIV (598): 700. 1879-08-30. hdl:2027/nnc2.ark:/13960/t2b85mh46.

- ^ a b "For Sale". American Machinist. New York: Hill Publishing Company. 1906-05-18. hdl:2027/mdp.39015080284311.

- ^ a b c Howell 1896. p. 87.

- ^ a b c d "Triple-Cylinder Expansion Engine by Riley and Cowley". The Engineer. XIX (4). New York: Egbert P. Watson & Son: 37. 1890-02-15. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942491.

- ^ State of New York 1890. p. 114.

- ^ United States Government 1903. p. 112.

- ^ a b c d e f "Some Fast Steam Launches" (PDF). The Sun. New York. 1892-07-09. p. 4.

- ^ a b The American Yacht List. 1891. p. 186.

- ^ a b "Marine Engineering". The Railroad and Engineering Journal. LXIV (10). New York: M. N. Forney: 473. Oct 1890. hdl:2027/mdp.39015013032506.

- ^ a b c d "Mr. Lorillard's Steel Launch". Scientific American. LXII (6). New York: Munn & Co.: 89 1890-02-08. hdl:2027/pst.000062999625.

- ^ a b "Boats for Sale: No. 16107". The Rudder. XVI (3). New York: The Rudder Publishing Company: 215. Mar 1905. hdl:2027/mdp.39015022693595.

- ^ a b "Norton's Unsinkable Ship". The Engineer. XX (12). New York: Egbert P. Watson & Son: 134. 1890-12-06. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942491.

- ^ a b "A Fast Steam Launch". The Engineer. XXI (12). New York: Egbert P. Watson & Son: 135. 1891-06-06. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942509.

- ^ a b "Popular Miscellany". The Engineering Magazine. I (6). New York: The Engineering Magazine Company: 860–1. Sep 1891. hdl:2027/mdp.39015014810140.

- ^ "Name the Fastest Boat". The Record-Union. Sacramento, CA. p. 1.

- ^ Howell 1896. pp. 121–23.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1888. pp. viii–viiii.

- ^ a b c d e f g "The Riley & Cowley Steam Car". The Horseless Age. 10 (27). New York: Horseless Age Co.: 726–27 1902-12-31. hdl:2027/mdp.39015039811529.

- ^ Glasscock 1937. p. 332.

- ^ "For Sale". American Machinist. New York: Hill Publishing Co. 1905-05-18. p. 678. hdl:2027/mdp.39015080284311.

- ^ "Machine, Blacksmith and Pattern Shops" (PDF). New York Herald. 1905-06-11. p. 20.

- ^ "Eastern". The Iron and Machinery World. 4. Vol. XCVIII, no. 33. Chicago, IL: The Iron and Machinery World (Inc.). 1905-07-22. p. 22. hdl:2027/nyp.33433108238738.

- ^ "Reminiscences of a Machinist and Marine Engineer". The American Engineer. 21 (13). Chicago, IL: The American Engineer Publishing Co.: 124 1891-03-28. hdl:2027/uiug.30112061157910.

- ^ "Personal Mention and Engineers' Directory". The Engineer. XVIII (11). New York: Egbert P. Watson & Son: 125. 1889-11-23. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942483.

- ^ "Mrs. Lester Divorced" (PDF). The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1905-01-30. p. 2.

- ^ a b c Buckley, James M., ed. (1905-07-13). "Memoirs". The Christian Advocate. Vol. LXXX, no. 15. New York: Eaton & Mains. p. 599.

- ^ "Maritime Miscellany" (PDF). The New York Herald. 1879-03-14. p. 10.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1888. p. 128.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. p. 45.

- ^ The American Yacht List. 1889. p. 32.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1891. p. 182.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1888. p. 143.

- ^ Manning's Yacht Register for 1903. p. 46.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1888. p. 148.

- ^ Manning's Yacht Register for 1903. p. 49.

- ^ "At Lake George" (PDF). The Troy Daily Times. Troy, NY. 1888-08-14. p. 3.

- ^ "An Exciting Steam Yacht Race". The Engineer. Vol. 16, no. 5. New York. 1888-09-08. p. 55. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942475.

- ^ "A Swift Steam Yacht". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1889-06-06. p. 6 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. Part I. p. 18.

- ^ a b "Untitled". The Engineer. Vol. 18, no. 8. New York. 1889-10-12. p. 89. hdl:2027/mdp.39015010942483.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. p. 44.

- ^ Register of Iron and Steel Vessels. New York: The United States Standard Steamship Owners’, Builders’ and Underwriters” Association, Ltd. 1892. p. 114.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1891. p. 299.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. p. 14.

- ^ Manning's Yacht Register for 1903. p. 47.

- ^ "Roberts Boilers". Forest and Stream. Vol. 36, no. 2. New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Co. 1891-01-29. p. 38. hdl:2027/mdp.39015022405248.

- ^ "The Riley & Cowley Engines". Forest and Stream. Vol. 36, no. 5. New York: Forest and Stream Publishing Co. 1891-02-19. p. 97. hdl:2027/mdp.39015022405248.

- ^ Mannings Yacht Register 1903. p. 70.

- ^ "Untitled". The Engineer. XXIII (6). New York: Egbert P. Watson & Son: 63. 1892-03-19.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. I. p. 16.

- ^ The American Yacht List 1896. I. p. 27.

- ^ Lloyd's Register of American Yachts 1912. p. 117.

- ^ "Steam Yacht Telka". The World. New York. p. 11 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Manning's Yacht Register 1903. I. p. 64.

- ^ "Boats-For-Sale Illustrated List". The Rudder. 13 (3). New York: The Rudder Publishing Company: 169. Mar 1902. hdl:2027/mdp.39015022693579.

- ^ Manning's Yacht Register 1903. I. p. 35.

- ^ Lloyd's Register of American Yachts 1914. p. 182.

- ^ Lloyd's Register of American Yachts 1905. p. 94.

Bibliography[edit]

- The American Yacht List. New York: Thomas Manning. 1888. pp. 128, 143.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - The American Yacht List. New York: Thomas Manning. 1889. pp. 32.

- The American Yacht List. New York: Thomas Manning. 1891. pp. 182, 186, 299.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - The American Yacht List. Vol. I. New York: Thomas Manning. 1896. pp. 18, 27, 44, 45.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - Glasscock, C. B. (1937). The Gasoline Age: The Story of the Men Who Made it. Indianapolis and New York: The Bobbs-Merrill Company. p. 332.

- Half-Century's Progress of the City of Brooklyn. New York: International Publishing Co. 1886. p. 202.

- Howell, G. Foster (1896). Howell's Steam Vessels and Marine Engines. New York: The American Shipbuilder. pp. 87–88, 121–23.

- Lain, George T. (1868). Brooklyn City Directory For The Year Ending May 1st, 1868. Brooklyn, New York: J. Lain & Co. p. 521.

- Lloyd's Register of American Yachts. New York: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1905. p. 94.

- Lloyd's Register of American Yachts. New York: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914. p. 182.

- Manning's Yacht Register. Vol. I. New York: A. J. Manning. 1903. pp. 35, 47, 64.

- State of New York (1890). Fourth Annual Report of the Factory Inspectors of the State of New York (Report). James B. Lyon. p. 114.

- Stiles, Henry Reed (1884). The Civil, Political, Professional and Ecclesiastical History and Commercial and Industrial Record of the County of Kings and the City of Brooklyn, N.Y. from 1683 to 1884. Vol. II. New York: W. W. Munsell & Co. p. 691.

- United States Government (1903). Eight Hours For Laborers On Government Work. Hearings Before the Committee on Education and Labor of the United States Senate. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office. p. 112.

- Whittemore, Henry (1889). Free Masonry in North America from the Colonial Period to the Beginning of the Present Century: Also the History of Masonry in New York from 1730 to 1888: in Connection with the History of the Several Lodges Included in What is Now Known as the Third Masonic District of Brooklyn. New York: Artotype Printing and Publishing Co. pp. 301–2.