Poll tax riots

| Poll tax riots | |||

|---|---|---|---|

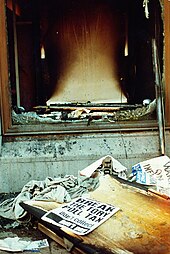

Scenes from the day of the event | |||

| Date | 31 March 1990 | ||

| Location | Trafalgar Square, London | ||

| Goals | Abolition of the poll tax | ||

| Methods | Political demonstration, riot | ||

| Parties | |||

| |||

| Lead figures | |||

No centralised leadership | |||

| Casualties | |||

| Injuries | 113 | ||

| Arrested | 339 | ||

The poll tax riots were a series of riots in British towns and cities during protests against the Community Charge (commonly known as the "poll tax"), introduced by the Conservative government of Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher. The largest protest occurred in central London on Saturday 31 March 1990, shortly before the tax was due to come into force in England and Wales.

Background

[edit]The advent of the poll tax was due to an effort to alter the way the tax system was used to fund local government in the UK. The system in place until this time was called "rates" and had been in place in some form from the beginning of the 17th century.[1] The rates system has been described as "a levy on property, which in modern times saw each taxpayer paying a rate based on the estimated rental value of their home".[1]

The Thatcher government had long promised to replace domestic rates, which were unpopular, especially among Conservative voters. They were seen by many as an unfair way of raising revenue for local councils.[2] It was levied on houses rather than people.[2]

The proposed replacement was a flat-rate per capita Community Charge—"a head tax that saw every adult pay a fixed rate amount set by their local authority".[1] The new Charge was widely called a "poll tax" and was introduced in Scotland in 1989 and in England and Wales a year later.[3] The Charge proved extremely unpopular; while students and the registered unemployed had to pay 20%, some large families occupying relatively small houses saw their charges go up considerably, and the tax was thus accused of saving the rich money and moving the expenses onto the poor.[4]

In November 1989 the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation was set up by the Militant tendency. Other groups such as the 3D (Don't Register, Don't Pay, Don't Collect) network provided national coordination for anti-poll tax unions who were not aligned to particular political factions.[5] After the leadership of the Labour Party refused to back any demonstration against the poll tax, the All Britain Federation called a demonstration in London for 31 March 1990, the day before the tax was due to be launched.[6]

During the early months of 1990, over 6,000 anti-poll tax actions were held nationwide, with demonstrations in cities around England and Wales drawing together thousands of protestors,[7] in a wave of protests which attracted notably large numbers in the South West.[8] On 6 March, a 5,000-strong demonstration in Bristol escalated into clashes, leading to mounted police charging the crowd and arresting 26 demonstrators, with injuries being sustained by both sides.[9] The following day, police baton charged demonstrators in Hackney, escalating the demonstration into a riot, during which 50 high street shop windows were smashed and 56 rioters were arrested.[10] Demonstrations were routinely called in places where councils discussed the poll tax, some resolving peacefully and others escalating into riots, with numerous cases of protestors storming council chambers and forcing meetings to be called off - although none prevented the tax from being implemented. Both Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher and opposition leader Neil Kinnock responded by blaming the demonstrations on outside agitators, respectively calling them "rent a mob extremists" and "Toy Town revolutionaries".[11]

As coaches bound for London were booked all around the country, it soon became clear that the planned demonstration was going to be larger than the 20,000 expected by Militant, who were more focused on the non-payment campaign than political demonstrations. When campaigners met with Metropolitan Police and gave them an expected number of 30,000, the chief police officer responded with laughter, as their own intelligence indicated far fewer numbers.[12] In acknowledgement of the square's capacity, the organisers asked to divert the march to Hyde Park but were denied.[13]

Protest in Trafalgar Square

[edit]

By 2:30 p.m. on 31 March 1990, Trafalgar Square was nearing its capacity. Unable to continue moving easily into Trafalgar Square, at about 3 p.m. a march stopped in Whitehall. The police, worried about a surge towards the new security gates of Downing Street, blocked the top and bottom of Whitehall, and lined the pavement refusing to let people leave the road. Additional police units were dispatched to reinforce the officers manning the barrier blocking the Downing Street side of Whitehall. The section of the march which stopped opposite Downing Street reportedly contained veteran anarchists and a group called "Bikers Against The Poll Tax", some of whom became aggravated by reportedly heavy-handed arrests, including one of a man in a wheelchair.[14]

From 4 pm, with the rally nearly officially over, contradictory reports began to arise. According to some sources, mounted riot police (officially used in an attempt to clear Whitehall of protesters) charged out of a side street into the crowd in Trafalgar Square. Whether intentional or not, this was interpreted by the crowd as a provocation, fueling anger in the Square where the police had already been pushing sections of crowd back into corners, leaving no way out except through the police. At 4:30 pm, four shielded police riot vans drove into the crowd (a tactic in dealing with mass demonstrations at the time) outside the South African Embassy, attempting to force through to the entrance to Whitehall where police were re-grouping. The crowd attacked the vans with wooden staves and scaffolding poles. Soon after, rioting began to escalate.[15]

The demonstrators mixed in with the general public. By midnight, released figures claimed 113 were injured, mostly members of the public, but also police officers, and 339 people had been arrested.[16] Scuffles between rioters and police continued until 3 am. Rioters attacked numerous shops, most notably Stringfellow's nightclub, and car showrooms, and Covent Garden cafés and wine bars were set ablaze, along with motor vehicles.[17]

Responses

[edit]The response of the Metropolitan Police, the Government, the Labour Party and the labour movement and some of the Marxist and Trotskyist left, notably the Militant tendency, was to condemn the riot as senseless and to blame anarchists. Tommy Sheridan of Scottish Militant Labour condemned the protesters. The next day, Steve Nally, also a Socialist Party member and Secretary of the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation, said that they would "hold an enquiry and name names".[18] Many others denounced the All Britain Anti-Poll Tax Federation position and defended those who fought back against the police attacks. Danny Burns (secretary of the Avon Federation of anti-Poll Tax Unions) for example said: "Often attack is the only effective form of defence and, as a movement, we should not be ashamed or defensive about these actions; we should be proud of those who did fight back."[19]

The Socialist Workers' Party (SWP), which was blamed for the violence by some in the media and by Labour MP George Galloway,[20] refused to condemn protesters, calling the events a "police riot". Pat Stack, then a member of the SWP's Central Committee, told The Times: "We did not go on the demonstration with any intention of fighting with the police, but we understand why people are angry and we will not condemn that anger."[21]

A 1991 police report concluded there was "no evidence that the trouble was orchestrated by left-wing anarchist groups". Afterwards, the non-aligned Trafalgar Square Defendants Campaign was set up, committed to unconditional support for the defendants, and to accountability to the defendants.[22] The Campaign acquired more than 50 hours of police videos. Use of these was influential in acquitting many of the 491 defendants, suggesting the police had fabricated or inflated charges.[16]

In March 1991, the police report suggested additional contributing internal police factors: squeezed overtime budgets which led to the initial deployment of 2,000 men, insufficient given the number of demonstrators, a lack of riot shields (400 "short" riot shields were available), and erratic or poor-quality radio, with a lag of up to five minutes in the computerised switching of radio messages during the evening West End rioting. Prime Minister Thatcher was at a conference of the Conservative Party Council in Cheltenham; the poll tax was the focus of the conference. As coverage of the demonstrations unfolded, speculation developed for the first time about Thatcher's position as leader. In November 1990, Thatcher would face a Party leadership challenge, and would lose to John Major in the subsequent leadership election.

Abolition of the tax

[edit]Vehement national opposition to the poll tax (which was especially strong in the north of England and Scotland) was the most important factor in its abolition. An opinion poll conducted in 1990 indicated that 78% of those polled and who expressed an opinion gave preference to alternative means of taxation.[23]

John Major, initially in his first Prime Minister's Questions, only said his government would "look at" the Community Charge, and if necessary "ensure it is accepted throughout the country", though it is a common misconception that he instantly scrapped it. In 1991, he then announced in a parliamentary speech as Prime Minister that the poll tax was to be replaced by Council Tax. The council tax came into effect in 1993. Similar to the previous system of rates, the new system set tax levels on property value. Although it was not directly linked to income, the council tax took ability to pay into consideration, unlike the poll tax.[1]

See also

[edit] Anarchism portal

Anarchism portal- 1990 Strangeways Prison riot

- 2011 United Kingdom anti-austerity protests

- Class conflict

- List of riots in London

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d Nick Collins (9 March 2011), "Local government funding timeline: From rates to poll tax to council tax", The Daily Telegraph, retrieved 22 May 2018

- ^ a b Margaret Thatcher: The Authorized Biography, Volume Two: Everything She Wants, p. 58–9, at Google Books

- ^ "Secret papers reveal push to 'trailblaze' poll tax in Scotland", BBC News, 30 December 2014, retrieved 10 October 2015

- ^ Wilde, Robert, "Community Charge / Poll Tax", About Education, archived from the original on 6 September 2015, retrieved 10 October 2015

- ^ Burns 1992, p. 78.

- ^ Hannah 2020, p. 81.

- ^ Burns 1992, pp. 83–84; Hannah 2020, pp. 81–82.

- ^ Burns 1992, pp. 83–84.

- ^ Burns 1992, p. 84.

- ^ Burns 1992, pp. 84–85.

- ^ Burns 1992, p. 85.

- ^ Hannah 2020, p. 82.

- ^ Sharpe, James (8 September 2016). A Fiery & Furious People: A History of Violence in England. ISBN 9781446456132.

- ^ Channel 4 Critical Eye documentary, "Battle of Trafalgar", 9 July 1990, Despite TV

- ^ britishculturearchive (24 January 2020). "Protests and Riots in Thatcher's Britain | Photographs by Andrew Moore". British Culture Archive. Retrieved 14 November 2023.

- ^ a b Verkaik, Robert (21 January 2006), "Revealed: How police panic played into the hand of the poll tax rioters", The Independent, p. 10, retrieved 17 May 2008

- ^ "Poll Tax Riots & Protests, 1990 | Photographs by David Corio". British Culture Archive. Retrieved 8 February 2024.

- ^ London: Anti Poll Tax Riot: The Violence | Archive Footage, ITN Source, 1 April 1990, retrieved 8 August 2012

- ^ Burns 1992, p. 116.

- ^ "Poll tax spurs riot", The Gainesville Sun, 1 April 1990

- ^ "Bloody battle of Trafalgar – London poll tax riot", The Sunday Times, 1 April 1990

- ^ Gross, David M. (2014), 99 Tactics of Successful Tax Resistance Campaigns, Picket Line Press, pp. 37–38, ISBN 978-1490572741

- ^ Wood, Nicholas; Oakley, Robin (30 April 1990), "Poll shows 35% want to bring back rates", The Times, MORI found 35% wanted 'Rates', 29% a local income tax, 15% a 'Roof tax' combining property values with ability to pay, 12% the poll tax, with 9% in favour of neither of these options.

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link)

Bibliography

[edit]- Burns, Danny (1992). Poll Tax Rebellion. Stirling: AK Press. ISBN 1873176503. OCLC 26200325.

- Hannah, Simon (2020). Can't Pay, Won't Pay: The Fight to Stop the Poll Tax. London: Pluto Press. ISBN 978-0745340852. OCLC 1119768767.

Films

[edit]- "The Battle Of Trafalgar". Despite TV. 18 September 1990. Channel 4.

External links

[edit]- On This Day, 31 March 1990, BBC archive

- Gallery of photographs from 31 March riot

- Role of The Militant in defeating the poll tax

- The Rise of Militant

- Politicising the Poll Tax, Anarchist Workers Group

- "The Poll Tax Revolt" documentary

- Poll Tax Riot: The day that sunk Thatcher's flagship, The Socialist Worker

- Anarchist Communist Federation: Anti-poll tax articles from Organise! (magazine), scanned articles about the anti–poll tax struggle (1988–1992) from Issues 14 to 27 inclusive

- 1990s in the City of Westminster

- 1990s crimes in London

- 1990 crimes in the United Kingdom

- 1990 in London

- 1990 riots

- Civil disobedience in the United Kingdom

- March 1990 crimes

- March 1990 events in the United Kingdom

- Protests in the United Kingdom

- 20th-century riots in London

- Riots and civil disorder in England

- Poll taxes