Peter Baker (slave trader)

Peter Baker (1731–1796) was an English slave trader.[1] He formed the Liverpool slave trading company Baker and Dawson with his son-in-law John Dawson. In the period between 1783 and 1792, Baker and Dawson was the largest company of slave traders in England. They had an exclusive contract with the Spanish government to supply enslaved people to the Spanish colonies. In 1795, he became Mayor of Liverpool.[2]

Slave trade[edit]

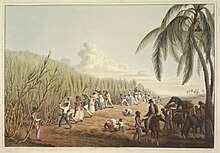

Peter Baker was born in West Derby, Liverpool.[3] In the period between 1783 and 1792, Baker and his partner John Dawson were the largest firm of slave traders in England.[4] In 1784 their firm, Baker and Dawson, secured a contract with the Spanish government to supply enslaved people to Spanish America.[5] The contract was arranged by two intermediaries named Barry and Black and gave them exclusive access to disembark enslaved people in Cuba and the other Spanish West Indies islands. Barry and Black arranged the on-island functions, such as the holding pens and transportation. In 1786, Baker and Dawson signed a new contract to supply enslaved people taking over these functions themselves. The contract had a fixed price of 155 Pesos for each enslaved person.[6] In total they supplied 11,000 enslaved people that they valued at more than £350,000.[7]

The rulers of the Spanish Caribbean islands became dissatisfied with the sickly nature of Africans and began to return them. Records show Baker and Dawson carried more kidnapped people per ship tonnage than their contemporaries. In 1788, Dawson complained to the UK government about the regulation of the number of the enslaved allowed per ship tonnage.[8] Records do not indicate what happened to those people, most likely they were sold in nearby Jamaica.[8] Even after the Spanish colonies were opened to other slave merchants, Baker and Dawson remained the largest slave trading company in the Spanish Caribbean.[4]

Baker and Dawson had completed over 100 slave voyages by the early 1790s. Dawson, who also slave traded without Baker, went bankrupt in 1793 during a credit crisis.[1]

Capture of Carnatic[edit]

On 28 October 1778 Dawson captured a French East Indiamen named Carnatic.[9] He was captaining Mentor, owned by Messrs. Baker & Co., that had 400 tons burthen, 28 guns, and a crew of 102 men. Carnatic had a cargo that included a box of diamonds valued at £135,000. This was said to be the richest prize ever taken and brought safely into port by a Liverpool privateer.[9]

Personal life[edit]

Baker was the father-in-law of John Dawson who became his business partner in the firm Baker and Dawson.[9]

Carnatic Hall[edit]

Baker used his fortune to build the country house Carnatic Hall in Mossley Hill, Liverpool. It was named after Carnatic, which Dawson had captured in 1778. The house burned down in 1890, was rebuilt, and was demolished completely in 1964. The University of Liverpool purchased the site for a student hall of residence that they named Carnatic Hall. The student residence closed in 2018.[1]

Corporation of Liverpool[edit]

Baker was the Mayor of Liverpool in 1795.[2] Liverpool was Britain's pre-eminent slave trading city and twenty-five former mayors of Liverpool were slave traders.[10] In 1788, a House of Commons bill was passed that regulated slave ships. The bill caused a hostile reaction from the Corporation of Liverpool, who petitioned the House of Lords to throw out the bill.[11] Williams writes "The spectacle of the corporation, the members of which must have been perfectly well acquainted with the horrors of the slave trade, appealing to the House of Lords to uphold the infamy of the town, is a melancholy, but striking example of the power of usage and self-interest in blunting the moral vision of men".[11]

List of vessels owned by Baker & Dawson[edit]

Baker and Dawson were the largest firm of slave traders in England.[4] Vessels they owned included:

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Clements, Max (June 21, 2020). "Stark truth that not just city centre benefited from slavery cash". Liverpool Echo. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ a b "Former Mayors and Lord Mayors". Liverpool Town Hall. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Richardson 2007, p. 194.

- ^ a b c Behrendt, Stephen. "The Captains in the British Slave Trade from 1785 to 1807" (PDF). The Historic site of Lancashire and Cheshire. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ Postigo 2019, p. 1.

- ^ Postigo 2019, p. 4.

- ^ Richardson 2007, p. 32.

- ^ a b Postigo 2019, p. 5.

- ^ a b c Williams 1897, p. 239.

- ^ Long, Chris (January 15, 2020). "The slavers and abolitionists on Liverpool's streets". BBC News. Retrieved July 6, 2021.

- ^ a b Williams 1897, p. 611.

Sources[edit]

- Morgan, Kenneth (2007). Slavery and the British Empire. Oxford University Press.

- Postigo, José Luis Belmonte (2019). "A Caribbean Affair: The Liberalisation of the Slave Trade in the Spanish Caribbean, 1784-1791". Culture & History Digital Journal. 8 (1): 014. doi:10.3989/chdj.2019.014. hdl:10261/259058.

- Richardson, David (2007). Liverpool and Transatlantic Slavery. UK: Liverpool University Press. ISBN 978-1-84631-066-9.

- Williams, Gomer (1897). History of the Liverpool Privateers and Letters of Marque: With an Account of the Liverpool Slave Trade. W. Heinemann.