Old Smyrna

Site of Old Smyrna asty on Tepe Kule at Beyraki, Izmir. Yamanlar Daği rises in the background. Pillars of the Temple of Athena are in evidence. This is not to be taken as the whole asty, or the whole polis, which included territory over the entire east end of the Bay of Smyrna. It probably was the center of the polis. | |

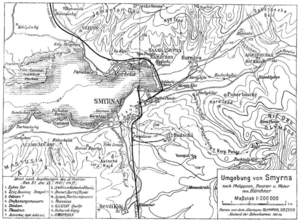

The Pauly-Wissova map showing the location of Old Smyrna with respect to Smyrna. Both are included in modern Izmir, which covers the whole east end of the bay. | |

| Coordinates | 38°27′51″N 27°10′11″E / 38.46407°N 27.16974°E |

|---|---|

| Type | Polis |

| Part of | Aeolis at first, then Ionia, probably a member of the Ionian League, but if not, then an unofficial associate. |

Old Smyrna (Greek Παλαιὰ Σμύρνα, Palaia Smyrna, Turkish Eski Smyrna) is an ancient Greek exonym first known to have been applied by Strabo (14.1.37) to a city of the endonym Σμύρνα, Smyrna. It had existed at the same location on the Bay of Smyrna, Turkey, since prehistoric times. Old Smyrna experienced what was termed dioecism (dioikismos), the removal of a city from its subordinate constituents, the reverse of synoecism, at the hands of its Lydian conquerors under their king, Alyattes, in 585 BC, in the Archaic Period of Greece. It is mentioned by Herodotus (1.16.2). Such a procedure, which was standard among the ancient Greeks,[1] razes the center of the city and distributes the population to komai, or "villages," (where they may have lived anyway). Apparently they did not suffer andrapodismos, the massacre of the men and the sale of the women and children into slavery, but were allowed to live komedon, "in villages," albeit without a polis of their own.

The remains of Old Smyrna are known from several excavations in the neighborhood of Beyraki, Izmir. Its development can be traced for over 700 years. According to ancient sources, Smyrna was founded by Aeolians, but later conquered by Colophon and was therefore regarded as an Ionian city.[2] Having become part of the Lydian empire in 585 BC, its territory became part of the Achaemenid Empire in 545 BC. Around 330 BC, the rulers of Macedon synoecised a new city from the villages of the old including any that had been founded since then.[3]

The main difference besides the demographic changes of time is that a new site was chosen for the asty, or political center, about 4 km (2.5 mi) from the previous. Other than that it cannot be said that the polis was relocated. It had all the villages it would have had, had it not been dioecized. The old asty became a municipal unit of the new city. The ancients did not use the term new, however. Moderns have chosen it in opposition to Strabo's old, and politically there was a new city. The ancient sources chose to regard it as the same Smyrna. Only in 1930 did the more recent population break away from the ancient name, substituting the Turkish form, Izmir, instead.[4][a] For all that, Izmir is derived from Smyrna.

Localization[edit]

Locality problems[edit]

There are a number of difficulties with the Strabo passage. Smyrna is razed and un-synoecized in 585 BC not to be reassembled for 400 years, which would be 185 BC. This reassembly, presumably of the villages, must be another synoecism. Different synoecisms create different cities, yet Strabo considers them in some way the same Smyrna, despite the distinction of one being "old." This turn of the phrase is far-fetched, as after 400 years neither the people nor their material objects can be the same in any significant way, any more than the city of New York continues York, England. Izmir also is considered Smyrna even though yet more different still.

There is, however, a common element. The territory of a polis is every bit as much the polis as the asty, or urban area. Smyrna's territory probably always was about the same; that is, the land around the Bay of Smyrna.[5] Any polis in that territory would have to be Smyrna. If some other polis were there, its territory would belong to it, and have its name, not Smyrna's. Any number of differently named villages could be there.[b]

Having reached this conclusion the investigators' next gambit was to identify villages of the komedon to see what geographic area they covered. The sources stating or implying borders as well as the boundary stones discovered by archaeologic survey were useful for this purpose.[c] Hill is able to use this material to reconstruct the borders of the Ionian states.[5][d]

For Smyrna, imagine that the border is a line leaving the north coast of the bay in a northward direction, ascending the slopes of the range enclosing the east end of the bay, veering always to the right in an ovoid line following the ridge or the upper slopes on the bay side until it comes around to the south of the bay and heads north to intersect it. The salient locations are as follows:

| Location point | Name | Coordinates | Distance from asty | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| North coast of bay | Mavişehir at the mouth of Peynircioğlu creek | 38°28′03″N 27°04′42″E / 38.467441°N 27.078342°E | 8 km (5.0 mi) | Intersection of 8-km circumference with bay |

| Northern extremity | Sancakli Kalesi on Adatepe | 38°31′22″N 27°08′57″E / 38.52286°N 27.14913°E | 6.75 km (4.19 mi) | Hellenistic permanent fort on a double peak with a ring wall 260 m (850 ft) long Watch tower, cistern with runoff for rain capture. Pottery is all Hellenistic. Elevation about 360 m (1,180 ft), south slope of Yamanlar. North slopes are in Aeolia. View of Smyrna, use hypothesized to be to protect the northern approach.[6] |

| Eastern extremity | Belkahve | 38°27′29.4″N 27°19′5.31″E / 38.458167°N 27.3181417°E | 12.95 km (8.05 mi) | Walled fort overlooking Belkahve Pass from the north. Elevation of pass is 268 m (879 ft); of fort, 450 m (1,480 ft). Its hill is conical from which stone was quarried to build an Archaic-period wall dated 7th century BC. Otherwise pottery is Hellenistic and Roman. Cistern. Unexcavated. Guards Smyrna on the east.[7] |

| Southern extremity | Akçakaya kalesi | 38°21′4.07″N 27°4′30.61″E / 38.3511306°N 27.0751694°E | 4.07 km (2.53 mi) | Walled akropolis of a settlement on the border with Klazomenai at Limontepe Mevkii. Elevation 430 m (1,410 ft). Cistern. Residence. Pottery Hellenistic and Roman except for one Classical sherd.[8] |

| South coast of bay | Narlidere | 38°23′06″N 26°56′16″E / 38.38509°N 26.93789°E | 21.78 km (13.53 mi) |

Not surprisingly the city of Izmir covers about the same territory as ancient Smyrna, except that Izmir extends over prograded land and has managed to inhabit more of the mountainous land. The territory must have filled up during the (new) Smyrna period. There was simply nowhere else to build. Currently over this relatively small territory are roughly 4 million people living on 12,012 km2 (4,638 sq mi). Izmir is the 3rd largest city of Turkey.[4]

Smyrna's conquerors that did not actually inhabit it had some trouble declaring it to be null and void or reducing it to villages. It was already too crowded to fit the village mold. Strabo himself said that it existed on the mountains, and filled up the plains by the harbor, and had a city wall, but only partly fit within it. It is not correct to say that anyone abandoned it or moved out of it to somewhere else or that it was ever a single settlement that could change locations. A polis is by definition a synoecism of multiple settlements. Whatever the site at Beyrakli was, it was not the single site of a single settlement, Smyrna. That the political center moved from there to a few miles away, there is little scholarly doubt. However no source gives any hint of why the Macedonian sponsors made that decision.

Strabo implies that some sort of qualitative improvement was the main intent. The new city, he says, has room for long, straight streets, stone pavements, more and better public buildings, additional monuments, and above all a closed harbor offered by the barrier islands before the mouth of the River Meles. He does have a criticism. The engineers, he says, neglected to build sewers, so that waste water was continually in the streets. Whether this problem remained so continuously would have to be the topic of another investigation, but in the 20th century the bay was too badly polluted even to bathe in. New sewage processing facilities brought an improvement in the 21st century.

The ever-changing terrain[edit]

The Gulf of Izmir shown on today's maps is not the one on which Old Smyrna was founded and existed until the dioecism. The general features are the same, but not the details of the coastline. The same thing may be said of most of the other cities of Ionia, manifestly because they were all subject to the same geologic pressures, some few being in a position to be less influenced by them.

Most generally the land mass of Anatolia is extending (stretching) in a N-S direction due to tectonic factors (plate movements). The extension is opening up normal faults in an E-W direction, creating graben, or sunken valleys, through which the rivers of Anatolia drain to the Aegean Sea.[9] As extension is on-going, and these faults are still active, the danger of earthquakes in the region is high.

Smyrna was placed on the south shore of the mouth of the Gediz River (ancient Hermus), which is the 2nd largest river of Turkey, flowing through the Alaşehir graben, named after the city inland on it (ancient Philadelphia). The L shape of the gulf is caused by the extensive aggradation of the Gediz into the drowned bay, creating the Foça Peninsula (ancient Phocaea) as the delta of the Gediz.

Chronology problems[edit]

The chronological difficulties with the Strabo defining passage of Old Smyrna are with the starting and ending points of the komedon, the supposed village period between dioecism and new synoecism. Moderns tend to confuse these events in the life of a polis with the foundation and destruction of modern cities, which are allowed take all the time the builders or destroyers please and go through whatever phases they please. A polis on the other hand no matter what previous phases cannot be a polis without a synoecism, which must happen on a specific date, like the date of a birth or a death. Every Greek polis looked back on its foundation and commemorated the founder(s). No foundation, no polis, and this was the legal requirement exploited by the Lydians. No polis, no army, no legal standing, etc.

Old Smyrna flourished in the Archaic Period and was stopped in 585 BC[e] by the dioecism of the Lydians, about half-way through the period. The archaeologists had every right to expect to find an Archaic layer succeeded by a destruction and cut off by it from all habitations and layer material until the Hellenistic period, but that is not at all what they found. The archeology often does not match the political history or the supposed political history.

The archaeologist, Ekrem Akurgal, excavating the site of Old Smyrna at Bayrakli, found no political clarity there. In his reconstruction of the structures and the main street, 500-600 houses existed from 630 BC to 545 BC, supporting a population of about 3000 people in a locale where Strabo stated there ought not to be any.[10] John Manuel Cook, Akurgal's co-director of the excavation, publishing after Akurgal,[11][f] expresses their conclusions about the date of the dioecism as follows.

First of all, the date deduced from the passage of Herodotus (see Introduction above) is based on an incorrect interpretation. He lists the campaigns of Alyattes' reign as though they were in chronological order: a war against the Medes under Cyaxares, expulsion of the Cimmerians, the capture of Smyrna, and the invasion of Clazomenae. Thus the sack of Smyrna has been believed to have followed the Median War. As conflict with the Medes was brought to an end in 585 BC by both parties when it was interrupted by the eclipse of 585 BC, the Lydians were believed to have gone on immediately to the sack of Smyrna. Cook rejects this interpretation mainly because it does not fit the archaeology.

The archeologists' next ploy was to rearrange the campaigns. They assumed that Alyattes would deal with his neighbors, the Ionians, first. There was no denying the existence of a "general destruction level ... recognized in all the main sectors of excavation of the site."[11] This came to be called "the Alyattes destruction levels."[h] The pottery phase in the level was "Early Corinthian," used to date it.[12][i] As Cook reported, the date of Early Corinthian could not be brought up to over 600 BC. As it turns out, there was an earlier eclipse of the sun at 610 BC. Others suggested an eclipse of the moon if they were fighting by moonlight. The excavators chose 600 BC as the earliest historical and latest archaeological date.

Selection of an early date for the dioecism, although historically possible and archaeologically true, does not solve the problem of continued pottery finds when there should have been none or few. The archaeologists' solution, reported by Cook, is this. Immediately after the destruction there was a period of desolation in the asty and deficit of pottery, in which "the old site seems to have been almost totally abandoned." It lasted for only the first quarter of the 6th century BC. Subsequently, at the end of Alyattes' reign, there was a "planned reoccupation" signified by a build-up of various types of pottery. The site was being reinhabited, but there is no evidence of its being a polis. What is new about this resettlement is the Lydian pottery. Apparently a new village was being formed of mixed Greek and Lydian population. There was even more of a floruit in the reign of Alyattes' son, Croesus.

The economic circumstances of Old Smyrna after its destruction were unlike those of the other Ionian cities. There had been conflicts between Lydia and some other Ionian cities but never with such vindictive results. Miletus had been engaged in an extended conflict, but opted at last for a peace treaty. After Smyrna, Alyattes went for nearby Clazomenae, and was driven off. He let it go. Subsequently, he made a defense treaty with Colophon, which he used as an opportunity to massacre Colophon's cavalry while they were celebrating their newfound brotherhood. He annexed Colophon as an asset.

Vindictiveness was not generally a policy of the Lydian kings. They were always interested in prosperity and profit. Far from being the "barbarians" the Greeks tagged them to be, they went a long way towards civilizing the Greeks.[13] It was they who invented currency. They made significant cultural contributions to art and architecture. They always insisted that the Ionian cities include large native populations, who interacted with and intermarried the Greeks.[14] Some of the random surviving inscriptions are written in Lydian or Carian script, some of them bilingual.[15] Many of the historical Ionians could claim a Lydian or Carian relative. What remains puzzling is the intensity and tenacity of the king's wrath against Smyrna. Every structure was razed beyond recovery, while the population were told to get out and stay out, at least for the rest of Alyattes' reign.

Elsewhere the collaboration of Lydians and Ionians made both constituents prosperous. They established free markets and shared ports and trade facilities. Croesus boasted of his wealth to an Athenian in exile, Solon, and graciously bestowed upon him the honorary ownership of Miletus. Solon replied with his still-remembered remark, call no man blessed until he is dead, the recounting of which by Croesus at his execution caught the fancy of the Persian king and saved his life. Akurgal defines the period 650-494 BC as "The Golden Age of Ionia." Of it he says "Ionia was at its highest period of prosperity...."[16]

- Ionian golden age ceramics in the Izmir Archaeological Museum

The fortunes of the village of Old Smyrna were highly variable over this time. Cook calls the whole time from the dioecism to the synoecism "the village period."[17] The village finally escaped Alyattes at his death in 560 BC, and was well-treated by Croesus, but never restored as a polis. The defeat of the Lydians against the Persians in 546 BC seems to have made little difference to the Ionians. There was no archaeological effect on Old Smyrna.[18] The anecdotes in Herodotus suggest that Cyrus the Great admired the Ionians. He invited their philosophers to court and sought the advice of their military men. Whether this leniency encouraged the Ionians to revolt is not certain, but revolt they did, 499-493 BC, with a complete loss of the king's good favor (now Darius the Great). The abandonment of Smyrna and Clazomenae at this time is attributed to the king's bad favor.[j]

Fifth-century Athens is known as the golden age of Athens. It began with the defeat of the Persian Empire at the hands of the Athenians as their army attempted to overrun Greece from the northeast. Tiring of the Ionian Revolt, the Persians defeated them and then perceived that they would have to defeat their friends and allies on the mainland as well. They didn't get to enjoy their victory over the Ionians for long, as they were expelled from Greece and from Ionia in a series of battles with the Athenians and Lacedaemonians, now too well known to mention. Athens then reached a floruit of art, philosophy, literature and government, before committing suicide in a life-and-death struggle with the Lacedaemonians and their allies, the Peloponnesian War, which they lost at the end of the century. Ionia reverted to the Persians. Meanwhile, the Ionian League had pretty well been supplanted by the Delian League, nowadays characterized by the scholarly exonym, Athenian Empire.

Smyrna is of note as not being part of any of it, because it was not extant, and yet something was there on the hill at Old Smyrna. Cook points out that the wells, the water supply, were used continuously since the golden age of Smyrna. There was some 5th-century pottery on the hill, perhaps from a few buildings. The territory of Smyrna is not likely to have been abandoned, or the other poleis would have moved in on it. There is some slight evidence that, although not a polis, it was respected as a credible political entity. The Athenian Empire had issued the Coinage Decree specifying that the cities in their League must not issue silver coinage on penalty of death.[19] The decree was required to be published in stone in the agora of each polis as warning. Smyrna was not then a polis but a fragment of the decree was found on the hill and was documented. It was lost in 1855. The fragment raises as many questions as it answers, such as why, if the Smyrnaeans were under no constraint, did they not rebuild the city, and why the Athenians should accord the status of agora to a deserted and dilapidated collection of ruins. Obviously, if the population chose not to inhabit the hill, they were living happily nearby.

In the 4th century BC dense settlement again appeared on Bayrakli. The new settlers did not use the footprint of the prior settlements. The houses "were laid on an axis oblique to that of the sevemth century."[20] The edges of the hill were shored by a revetment. A new circuit wall was built. This unexplained renewal settlement was abandoned no later than 325 BC, with an upper layer of Black Glazed Ware.[21]

Cook is uncertain whether komedon means "plurality of villages" or "open settlement." Either way he suggests the walled district represents neither a polis nor a kome but was "the stronghold of a local governor or landlord" now that Athens' protection of the territory was gone. The wealth of the stronghold was trade. The old harbor was rebuilt. It exported grain and imported wine. This use of the site of Old Smyrna was the last of the Village Period. A new synoecism was about to follow.

Archaeology[edit]

This section is a brief history of professional archaeological surveys and excavations conducted within the territory of the polis of Old Smyrna leading to information about the Greek polis and any previous phases of any culture. The settlement or settlements within the territory are known to extend backward to prehistoric times and to comprise speakers of at least two language groups, Greek and Anatolian. Excluded from consideration are operations conducted within the territories of other poleis, such as Clazomenae, Ephesos, or Sardis, even though the cultures or periods of those places may partially or entirely parallel those Smyrna. Also excluded are operations within the territory that reveal information only on Greek (new) Smyrna or on Turkish Smyrna or Izmir.

Izmir was the subject of frequest visitation from the Middle Ages on by persons interested in discovering antiquities, perhaps because it was "on the pilgrimage route to Jerusalem."[22] Subsequently, in the 18th century professionals came specifically to examine the ruins. The more ostentatious new city caught their attention first, with its statues, columns, arches, and inscriptions. Richard Pococke (1704-1765) visiting Izmir in 1739 noticed some funerary tumuli upslope from Beyrakli on Yamanlar, called Mount Sipylus in classical antiquity. Richard Chandler (1737-1810) having investigated Pococke's tombs in 1764 on behalf of the Society of Dilettanti was the first to propose that Old Smyrna had been in that area of Yamanlar.

Archaeological excavations started in 1930/31 under Franz Miltner. From 1948 to 1951 British-Turkish excavations were under the direction of John Manuel Cook and Ekrem Akurgal. Since 1967 there have been further Turkish excavations. The archaeological excavations discovered a heavily destroyed temple for Athena,[23] a massive town wall[24] and several parts of the living quarters. Next to the town are also substantial ancient cemeteries.

Etymological speculation[edit]

From Smyrna to Izmir[edit]

In English, the city was called Smyrna into the 20th century. Izmir (sometimes İzmir) was adopted in most foreign languages. The historic name Smyrna is still used today in some languages, such as Italian (Smirne), and Catalan, Portuguese, and Spanish (Esmirna).

Theories of a Greek origin[edit]

Several explanations have been offered for its name. A Greek myth derived the name from an eponymous Amazon named Σμύρνα (Smyrna), which was also the name of a quarter of Ephesus. This is the basis of Myrina, a city of Aeolis.

In inscriptions and coins, the name often was written as Ζμύρνα (Zmýrna), Ζμυρναῖος (Zmyrnaîos, "of Smyrna").[25]

The name Smyrna may also have been taken from the ancient Greek word for myrrh, smýrna,[26][27][28] which was the chief export of the city in ancient times.[29]

The latest known rendering in Greek of the city's name is the Aeolic Greek Μύρρα Mýrrha, corresponding to the later Ionian and Attic Σμύρνα (Smýrna) or Σμύρνη (Smýrnē), both presumably descendants of a Proto-Greek form *Smúrnā. Some would see in the city's name a reference to the name of an Amazon called Smyrna said to have seduced Theseus, leading him to name the city in her honor.[30]

Theories of an Anatolian origin[edit]

The region of İzmir was situated on the southern fringes of the Yortan culture in Anatolia's prehistory, knowledge of which is almost entirely drawn from its cemeteries.[31] In the second half of the 2nd millennium BC, it was in the western end of the extension of the still largely obscure Arzawa Kingdom, an offshoot and usually a dependency of the Hittites, who themselves spread their direct rule as far as the coast during their Great Kingdom. That the realm of the 13th century BC local Luwian ruler, who is depicted in the Kemalpaşa Karabel rock carving at a distance of only 50 km (31 mi) from İzmir was called the Kingdom of Myra may also leave grounds for association with the city's name.[32]

Speculations of a prior origin[edit]

In ancient Anatolia, the name of a locality called Ti-smurna is mentioned in some of the Level II tablets from the Assyrian colony in Kültepe (first half of the 2nd millennium BC), with the prefix ti- identifying a proper name, although it is not established with certainty that this name refers to modern-day İzmir.[33]

Others link the name to the Myrrha commifera shrub, a plant producing the aromatic resin called myrrh that is indigenous to the Middle East and northeastern Africa, which was the city's chief export in antiquity.[34] The Romans took over this name as Smyrna, which is still the name used in English when referring to the city in pre-Turkish times. In Ottoman Turkish the town's name was ازمير Izmīr.[citation needed]

Prehistory, protohistory, and history[edit]

Prehistoric settlements, neolithic and chalcolithic[edit]

The region was settled at least as of the beginning of the third millennium BC, or perhaps earlier, as suggested by finds made in Yeşilova Höyük in excavations since 2005.

The city is one of the oldest settlements of the Mediterranean basin. The 2004 discovery of Yeşilova Höyük and the neighboring Yassıtepe, in the small delta of Meles River, now the Bornova plain, reset the starting date of the city's past further back than previously thought. Findings from two seasons of excavations carried out in the Yeşilova Höyük by a team of archaeologists from İzmir's Ege University indicate three levels, two of which are prehistoric. Level 2 bears traces of early to mid-Chalcolithic, and Level 3 of Neolithic settlements. These two levels would have been inhabited by the indigenous peoples of the area, very roughly, between the 7th millennium BC and the 4th millennium BC. As the seashore receded with time, the site was later used as a cemetery. Several graves containing artifacts dating roughly from 3000 BC, and contemporary with the first city of Troy, were found.[35]

The first settlement to have commanded the Gulf of İzmir as a whole was established on top of Mount Yamanlar, to the northeast of the inner gulf. In connection with the silt brought by the streams which join the sea along the coastline, the settlement to form later the core of "Old Smyrna" was founded on the slopes of the same mountain, on a hill (then a small peninsula connected to the mainland by a small isthmus) in the present-day neighborhood of Tepekule in Bayraklı. The Bayraklı settlement is thought to have stretched back in time as far as the 3rd millennium BC.[citation needed]

Anatolian occupation in the Bronze Age[edit]

It could have been a city of the autochthonous Leleges before the Greek colonists started to settle along the coast of Asia Minor at the turn of the second to first millennium BC.

Greek settlement[edit]

Achaean colonization[edit]

Archaeological findings of the late Bronze Age show a certain degree of Mycenaean influence in the settlement and the surrounding region, though further excavations of Bronze Age layers are needed to propose Old Smyrna of that time as a Mycenaean settlement.[36] In the 13th century BC, however, invasions from the Balkans (the so-called Sea Peoples) destroyed Troy VII, and Central and Western Anatolia as a whole fell into what is generally called the period of "Anatolian" and "Greek" Dark Ages of the Bronze Age collapse.

Aeolian colony[edit]

The early Aeolian Greek settlers of Lesbos and Cyme, expanding eastwards, occupied the valley of Smyrna. It was one of the confederacy of Aeolian city-states, marking the Aeolian frontier with the Ionian colonies.

Smyrna was also among the cities that claimed Homer as a resident.[37]

At the dawn of İzmir's recorded history, Pausanias describes "evident tokens" such as "a port called after the name of Tantalus and a sepulcher of him by no means obscure", corresponding to the city's area and which have been tentatively located to date.[38] The term "Old Smyrna" is used to describe the Archaic Period city located at Tepekule, Bayraklı, to make a distinction with the city of Smyrna rebuilt later on the slopes of Mount Pagos (present-day Kadifekale). The Greek settlement in Old Smyrna is attested by the presence of pottery dating from about 1000 BC onwards. The most ancient preserved ruins date back to 725–700 BC.

According to Herodotus the city was founded by Aeolians and later seized by Ionians.[39] The oldest house discovered in Bayraklı has been dated to 925 and 900 BC. The walls of this well-preserved house (2.45 by 4 metres or 8.0 by 13.1 feet), consisting of one small room typical of the Iron Age, were made of sun-dried bricks and the roof of the house was made of reeds. [citation needed]

Ionian colony[edit]

Strangers or refugees from the Ionian city of Colophon settled in the city. During an uprising in 688 BC, they took control of the city, making it the thirteenth of the Ionian city-states. Revised mythologies said it was a colony of Ephesus.[40] In 688 BC, the Ionian boxer Onomastus of Smyrna won the prize at Olympia, but the coup was probably then a recent event. The Colophonian conquest is mentioned by Mimnermus (before 600 BC), who counts himself equally of Colophon and of Smyrna. The Aeolic form of the name was retained even in the Attic dialect, and the epithet "Aeolian Smyrna" remained current long after the conquest.

The archaic city ("Old Smyrna") contained a temple of Athena from the seventh century BC.

A house found in Old Smyrna with two floors and five rooms with a courtyard, built in the second half of the 7th century BC, is the oldest known house having so many rooms under its roof. Around that time, people started to build thick, protective ramparts made of sun-dried bricks around the city. Smyrna was built on the Hippodamian system, in which streets run north–south and east–west and intersect at right angles, in a pattern familiar in the Near East but the earliest example in a western city. The houses all faced south. The most ancient paved streets in the Ionian civilization have also been discovered in ancient Smyrna. [citation needed]

Under or against the Lydians and Persians, the village period[edit]

When the Mermnad kings raised the Lydian power and aggressiveness, Smyrna was one of the first points of attack. Gyges (ca. 687–652 BC) was, however, defeated on the banks of the Hermus, the situation of the battlefield showing that the power of Smyrna extended far to the east. A strong fortress was built probably by the Smyrnaean Ionians to command the valley of Nymphi, the ruins of which are still imposing, on a hill in the pass between Smyrna and Nymphi.

According to Theognis (c. 500 BC), it was pride that destroyed Smyrna. Mimnermus laments the degeneracy of the citizens of his day, who could no longer stem the Lydian advance. Finally, Alyattes (609–560 BC) conquered the city and sacked it, and though Smyrna did not cease to exist, the Greek life and political unity were destroyed, and the polis was reorganized on the village system. Smyrna is mentioned in a fragment of Pindar and in an inscription of 388 BC, but its greatness was past.

The city's port position near their capital drew the Lydians to Smyrna. The army of Lydia's Mermnad dynasty conquered the city sometime around 610–600 BC[41] and is reported to have burned and destroyed parts of the city, although recent analyses on the remains in Bayraklı demonstrate that the temple had been in continuous use or was very quickly repaired under the Lydian rule.

Soon afterwards, an invasion from outside Anatolia by the Persian Empire effectively ended Old Smyrna's history as an urban center of note. The Persian emperor Cyrus the Great attacked the coastal cities of the Aegean after conquering the capital of Lydia. As a result, Old Smyrna was destroyed in 545 BC.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The author does not define "officially." In general it refers to the extensive reconstruction of the city and renaming all its streets, architectural, and topographical features with Turkish names that went on in the 1920's and 1930's. The conflagrations of 1923 had destroyed most of the city.

- ^ What appwars to be the prototype of the theory can be found in Cook 1959, pp. 17–19, The Smyrnaean Territory. Cook defines it region by region, opposing previous scholars who had believed some of these regions were independent poleis. The concept of polis had not been extensively studied, as it was in the late 20th and early 21st centuries.

- ^ Rubinstein 2004, p. 1099 after stating "numerous second-order settlements scattered all over Smyrnean territory, some of them fortified, may be dated to the period after the dioikismos," proceeds to name several from the Archaic and Hellenistic periods.

- ^ The numbers of the subsequent presentation not otherwise accounted for were derived by overlaying Hill's depiction of the borders of Smyrna onto a Google map. His depiction is in places slightly distorted compared to the satellite views, but there are other sources for some of the coordinates.

- ^ This conventional date is based on textual analysis. It was revised by the archaeologists. See below.

- ^ Akurgal's book, Alt-Smyrna I, came out in 1983. See Rubinstein.

- ^ The Corinthian pottery found in Beyrakli is catalogued in Anderson, J.K. (1959). "Old Smyrna: The Corinthian Pottery". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 53: 138–151. doi:10.1017/S006824540001306X. S2CID 246244262.

- ^ Cook also calls this event "the Lydian capture:" Cook 1959, p. 23. He later explains that the destruction came at the end of a "protracted siege" of the city walls succeeding finally with a siege ramp: Cook 1998, p. 134 The ruination was so complete that in the subsequent village occupation some structures were never rebuilt.

- ^ The sequence is given as Corinthian Transitional, 640-625; Early Corinthian 625-600

- ^ The king sent a couple of generals to sack cities in Ionia. Developing greater plans for the conquest of Greece he accepted the submission of the others, which may have inculcated the wrong idea about Greeks and Greece. When he sent envoys to Sparta demanding water and soil as a token of submission, they threw the envoys into a well saying "dig it out for yourselves." Ionians went with the Great King on his march to Greece. Even so they were exonerated and set free by the Athenians in the aftermath of battle.

Citations[edit]

- ^ Hansen 2004, pp. 120–121

- ^ Herodotus, Histories 1, 149

- ^ The history is summarized in Akurgal 1983, p. 128

- ^ a b Eylemer 2015, Abstract

- ^ a b Hill, David (2019). "The formation and development of political territory and borders in Ionia from the Archaic to the Hellenistic periods: A GIS analysis of regional space". Journal of Greek Archaeology. 4: 109. doi:10.32028/jga.v4i.476. S2CID 253864569.

- ^ Bean, G.E.; Duyuran, R. (1947). "Ada Tepe Again (Sancakli Kalesi)". Journal of Hellenic Studies. 67: 128–134. doi:10.2307/626786. JSTOR 626786. S2CID 163296620.

- ^ Göncü 2019, pp. 13–16

- ^ Göncü 2019, pp. 23–26

- ^ Uzel 2012, pp. 440–441, Figures 1-2

- ^ Rubinstein 2004, p. 1100

- ^ a b Cook, J.M. (1985). "On the Date of Alyattes' Sack of Smyrna". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 80: 25–28. doi:10.1017/S0068245400007486. S2CID 163790514.

- ^ Cook 1959, pp. 25–27

- ^ "The Ancient City of Sardis and the Lydian Tumuli of Bin Tepe". Unesco World Heritage Convention. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Kerschner, Michael (2010). "The Lydians and their World". Sardis. Retrieved 14 September 2023.

- ^ Jeffery, L.H. (1964). "Old Smyrna: Inscriptions on Sherds and Small Objects". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 59: 47. doi:10.1017/S0068245400006079. S2CID 194951665.

- ^ Akurgal 1962, p. 373

- ^ Cook 1959, p. 29

- ^ Cook 1959, p. 31 "Smyrna evidently offered no resistance to the Persians, since there is no sign of any fortification or widespread damage on the site...."

- ^ Meritt, Benjamin D. (1975). "Perikles, the Athenian Mint, and the Hephaisteion". Proceedings of the American Philosophical Society. 119 (4): 267–268.

- ^ Cook 1958, p. 30

- ^ Cook 1958, pp. 30–31

- ^ Akar Tanriver 2017, p. 68

- ^ Smyrna, Temple of Athena (Building), John M. Cook, R. V. Nicholls: The Temples of Athena, Old Smyrna Excavations. London 1998, ISBN 0904887286

- ^ Smyrna, Fortifications (Building)

- ^ Σμύρνα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ Pseudo-Apollodorus, Bibliotheke, iii.14.4 (Adonis), as quoted in Geoffrey Miles, Classical mythology in English literature: a critical anthology 1999:215.

- ^ σμύρνα, Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, on Perseus

- ^ List of ancient Greek words starting with σμύρν-, on Perseus

- ^ Weston, J. (2007). Patmos Speaks Today. Scripture Truth Publications. p. 27. ISBN 9780901860668. Retrieved October 10, 2014.

- ^ Molly Miller (1971). The Thalassocracies. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-0-87395-062-6.. See also Life of Homer (Pseudo-Herodotus) and Cadoux.

- ^ K. Lambrianides (1992). "Preliminary survey and core sampling on the Aegean coast of Turkey". Anatolian Studies. 42. British Institute at Ankara: 75–78. doi:10.2307/3642952. JSTOR 3642952. S2CID 131663490.

- ^ J.D.Hawkins (1998). "Tarkasnawa King of Mira". Anatolian Studies. 48. British Institute at Ankara: 1–31. doi:10.2307/3643046. JSTOR 3643046. S2CID 178771977.

- ^ Ekrem Akurgal (1983). Old Smyrna's 1st Settlement Layer and the Artemis Sanctuary. Turkish Historical Society.

- ^ Weston, John (2 May 2018). Patmos Speaks Today. Scripture Truth. ISBN 9780901860668 – via Google Books.

- ^ "Yeşilova Höyük excavations". Archived from the original on 2007-02-23. Retrieved 2007-02-21.

- ^ Wagner, Ana. "Carolina Digital Repository – The Ahhiyawa Question: Providing Archaeological Evidence for the interconnection between the Hittites and the Mycenaeans". cdr.lib.unc.edu. University of North Carolina. p. 14. Archived from the original on 21 May 2018. Retrieved 26 October 2017.

In Western Anatolia, both Old-Smyrna and Izmir display a degree of Mycenaean influence,...

- ^ Gates, Charles (2011). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece, and Rome. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781136823282.

- ^ Pausanias. The description of Greece, Volume 2, p. 38.

- ^ According to Herodotus, the Ionian seizure of the city from the Aeolians was celebrated deceit that had occurred in the following manner: Colophonians fleeing internal strife within their Ionian city had taken refuge in Old Smyrna. But soon afterward, these defectors had taken advantage of an opportunity that had presented itself when native Aeolian Smyrniots had gone outside the city ramparts for a festival in honor of Dionysos, and had taken possession of the city. They forced an agreement upon the former inhabitants, who were obliged to take all their movable assets in the city and leave.

- ^ Strabo xiv. (633 BC); Stephanus Byzantinicus; Pliny, Natural History v.31.

- ^ An earlier siege laid by Gyges of Lydia is recounted by Herodotus in the form of a story according to which the King of Lydia would have attacked the city to avenge the ill-treatment received from its inhabitants a certain Manes, a poet and a favorite of the sovereign.

Reference bibliography[edit]

Excavation reports[edit]

- Akurgal, Ekrem (1983). Alt-Smyrna I. Wohnschichten und Athenatempel. Ankara: Türk Tarih Kurumu.

- Cook, John M.; et al. (1998). Old Smyrna: Excavations: The Temples of Athena. Supplementary Volume No. 30. London: The British School at Athens. ISBN 0904887286.

- Cook, J.M. (1959). "Old Smyrna, 1948–1951". The Annual of the British School at Athens 53/54 1958/1959: 1–34.

- Nicholls, R.V. (1958). "The Iron Age Fortifications and Associated Remains on the City Perimeter". The Annual of the British School at Athens. 53/54: 35–137.

Other reference literature[edit]

- Akar Tanrıver, Duygu (2017). "Eski Smyrna'nın Keşfi (The Discovery of Old Smyrna)". SDÜ Fen-Edebiyat Fakültesi Sosyal Bilimler Dergisi (SDU Faculty of Arts and Sciences Journal of Social Sciences (in Turkish) (42): 67–77.

- Akurgal, Ekrem (1962). "The Early Period and the Golden Age of Ionia". American Journal of Archaeology. 66 (4): 369–379. doi:10.2307/502024. JSTOR 502024. S2CID 191373655.

- Eylemer, S.; et al. (2015). "The borderland city of Turkey: Izmir from past to the present". Eurolimes. 19: 159–184.

- Göncü, Hakan; et al. (2019). "An Evaluation of Some Defensive Structures In the Hinterland of Smyrna/İzmir" (PDF). Turkish Academy of Sciences Journal of Cultural Inventory (in Turkish). 19: 11–28.

- Hansen, M.H. (2004). "Introduction". In Hansen, M.H.; Nielsen, T.H. (eds.). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis (PDF). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rubinstein, Lene (2004). "Ionia". In Hanson, Mogens Herman; Nielson, Thomas Heine (eds.). An Inventory of Archaic and Classical Poleis. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 1053–1107.

- Uzel, Bora; et al. (2012). "Neotectonic Evolution of an Actively Growing Superimposed Basin in Western Anatolia: The Inner Bay of Izmir, Turkey". Turkish Journal of Earth Sciences. 21 (4): 439–471.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Old Smyrna at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Old Smyrna at Wikimedia Commons