Military history of Cambodia

| History of Cambodia |

|---|

| Early history |

| Post-Angkor period |

| Colonial period |

| Independence and conflict |

| Peace process |

| Modern Cambodia |

| By topic |

|

|

The earliest traces of armed conflict in the territory that constitutes modern Cambodia date to the Iron Age settlement of Phum Snay in north-western Cambodia.[1]

Sources on Funan's military structure are rare. Funan represents the oldest known regional political entity, formed by the unification of local principalities. Whether these events must be categorized as conflict remains unclear[2] More information is available for Funan's successor state - Chenla, which has been characterized as distinctly bellicose as it was established by the military subjugation of Funan.[3] Chenla's early aristocrats heralded authority by public display of their noble genealogies carved onto stone stelae all over Indochina. Later, rulers increasingly embraced the concept of divine Hindu kingship.[4]

The Khmer Empire's territory and integrity was maintained through the Royal Army, personally commanded by the king. Records exist for regular conflict with the kingdom's neighbors, Champa in particular, as the empire effectively controlled Mainland South-east Asia by the 12th century.[5] Nonetheless, the Khmer kingdom suffered a number of serious defeats, such as the Cham invasion and sack of Angkor in 1177. Khmer military supremacy declined by the early 14th century.[6] Since the rise of the Siam Sukhothai Kingdom and later the Ayutthaya Kingdom the empire experienced a series of military setbacks, unable to repel repeated attacks, that eventually caused its collapse followed by the Post-Angkor Period.

The period of decline and stagnation (around 1450 to 1863) nearly ended the Khmer aristocrat's royal dynastic sovereignty and unity of the Khmer people as the result of prolonged encroachments by its neighbours Vietnam and Thailand.[7] In 1863 the Cambodian king acquiesced in the establishment of a French protectorate over his country to prevent its imminent incorporation into Vietnam in the east and the loss of its western provinces to Thailand.[8]

No centrally organized military actions took place during the French protectorate, although notable was an 1883/84 nationwide revolt "which saw thousands of French troops do battle with shadowy bands of Cambodian guerrilla insurgents throughout the countryside". Several local uprisings are accounted for, which caused considerable problems for the colonial authorities. However, mainly reactions to French tax rulings and other perceived legislative injustices and without clear political objective, these endeavours had no decisive consequences.[9] French colonial troops engaged in several conflicts with Thailand and suppressed revolts in Vietnam and Laos.[10]

The Japanese incursion and 1945 coup d'état initiated a decade of political and ethnic re-emancipation of Cambodia, brought about without large-scale military action.[11] Since Cambodia's independence in 1954 the country was to be the stage for a series of proxy wars of the cold war powers, foreign incursions and civil wars, that only effectively ended with the UN Mandate in the early 1990s.[12][13]

Early history

[edit]

The earliest traces of armed and violent conflict have been found at the Iron Age settlement of Phum Snay in north-western Cambodia. A 2010 examination of skeletal material from the site's burials revealed an exceptionally high number of injuries, especially to the head, likely to have been caused by interpersonal violence. The graves contained a quantity of swords, other offensive weapons used in conflicts. The presence of shoulder decorations and armour suggests a distinct military and/or clan culture, that has, according to some authors similarities with the Thai Iron Age sites such as Noen U-Loke and Ban Non Wat.[4][14]

Funan is only known from Chinese sources, which according to most modern historians are doubtful. The polity was fully established around the 1st century CE and consisted of "walled political centers", which implies a desire to be prepared for some kind of conflict and to be protected from attacks. Some authors also argue that Funan was "expansionist" and might have maintained a sizeable navy that conquered regional coastal settlement centers.[15] However, the Champasak territory of Laos was aggressively incorporated, although this might have taken place after the establishment of Funan's successor state - Chenla.

Some modern historians such as M. Vickery have redirected research and focus on archaeology, local genealogy and examined the suspicious size fluctuations and curious shifts of central power that characterized Chenla. Consequently, they argue, that Funan and Chenla, in particular, are terms not to be taken too seriously and accept greater political and military division among the elite.[4] As contemporary Chinese sources on Chenla only provide factual reference points, such as the claim that by 616/617 CE the kingdom of Chenla is the region's new souvereign and...the conqueror of Funan. In 802 CE a powerful and contentious ruling dynasty united sizable territories and established the Khmer Empire.[16]

Khmer Empire

[edit]

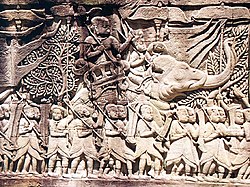

Bas-relief in galleries of the Angkor complex in Siem Reap elaborately depict the empire's land and naval forces and conquests of the period (802 to 1431), as it extended its dominions to encompass most of Indochina. Hindu warrior kings, who actually led troops in battle, did not customarily maintain standing armies but raised troops as necessity required [citation needed]. Historian David P. Chandler has described the relationship between the monarch and the military:

Though the king, who led his country into battle, sometimes engaged his chief enemy in single combat, Khmer military strength rested on the junior officers, the captains of militia. These men commanded the loyalty of peasant groups in their particular locality. If the king conquered a region, a new captain of militia would be enrolled and put under an oath of allegiance. The captains were simply headmen of the outlying regions, but their connection with the king enhanced their status. In time of war they were expected to conscript the peasants in their district and to lead them to Angkor to join the Khmer army. If the captains disobeyed the king they were put to death. The vast majority of the Khmer population were of the farmer-builder-soldier class.

Little is known conclusively about warfare during imperial Cambodia, but much has been assumed from the environment or deduced from epigraphic and sculptural evidence. The army was made up of peasant levies, and because the society relied on rice cultivation, Khmer military campaigns were probably confined to the dry season when peasant-soldiers could be spared from the rice fields. Battles were fought on hard-baked plains from which the paddy (or rice) had been harvested. Tactics were uncomplicated. The Khmer engaged their foes in pitched frontal assaults, while trying to keep the sun at their backs. War elephants were widely employed, for both tactical and logistical purposes. Late in the Khmer Empire, the ballista (a kind of catapult, often shaped like a giant crossbow) took its place in regional warfare. It probably was introduced to the Cambodians by Cham mercenaries, who had copied it earlier from Chinese models.[17]

Throughout the empire’s history, the court was repeatedly concerned with quelling rebellions initiated by ambitious nobles trying to achieve independence, or fighting conspiracies against the king. This was particularly true each time a king died, as successions were usually contested.[18]

The Khmer Empire's principal adversaries were the Cham of the powerful kingdom of Champa in modern central Vietnam and to a lesser extent the Pagan Kingdom to the west. Warfare was endemic and military campaigns occurred continuously. The Chams attacked by land in 1177 and again by water in 1178, sacked Angkor twice. The empire quickly recovered, capable to strike back, as it was the case in 1181 with the invasion of the Cham city-state of Vijaya.[19][20] In 1181 a young nobleman who was shortly to become Jayavarman VII, emerged as one of the great Khmer kings, raised an army and defeated the Chams in a naval battle. After Champa's decline began the rise of Cambodia's new enemies, the Siamese and the Vietnamese.

Post-Angkor Period

[edit]As some scholars assert that the decline of the Khmer Empire was, among other causes, mainly precipitated by the drain on its economy. Dynastic rivalries and slave rebellions are also considered to have affected the demise of the empire.

Military setbacks

[edit]Although a number of sources, such as the Cambodian Royal Chronicles and the Royal chronicles of Ayutthaya[21] contain recordings of military expeditions and raids with associated dates and the names of sovereigns and warlords, several influential scholars, such as David Chandler and Michael Vickery doubt the accuracy and reliability of these texts.[22][23] Other authors criticise this rigid "overall assessment", though.[24]

David Chandler states in A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing, Volume 2: "Michael Vickery has argued that Cambodian chronicles, including this one, that treat events earlier than 1550 cannot be verified, and were often copied from Thai chronicles about Thailand..."[6][25] Linguist Jean-Michel Filippi concludes: "The chronology of Cambodian history itself is more a chrono-ideology with a pivotal role offered to Angkor."[26] Similarities apply to Thai chronological records, with the notable example of the Ramkhamhaeng controversy.[27][28]

According to the Siamese Royal chronicles of Paramanuchitchinorot, clashes occurred in 1350, around 1380, 1418 and 1431.[29][30]

"In 1350/51; probably April 1350 King Ramadhipati had his son Ramesvara attack the capital of the King of the Kambujas (Angkor) and had Paramaraja (Pha-ngua) of Suphanburi advance to support him. The Kambuja capital was taken and many families were removed to the capital Ayudhya. At that time, [around 1380] the ruler of Kambuja came to attack Chonburi, to carry away families from the provinces eastwards to Chanthaburi, amounting to about six or seven thousand persons who returned [with the Cambodian armies] to Kambuja. So the King attacked Kambuja and, having captured it, returned to the capitol."[sic]

Colonial Cambodia

[edit]

Insurrections

[edit]Following negotiations by Cambodian King Ang Duong and Napoleon III for protection from Vietnam conquest and land loss by Thailand, a delegation of French naval officers concluded the French protectorate with King Norodom (1859–1904).The intervention of colonial France prevented further erosion of national and cultural integrity of Cambodia and ended territory loss.[31][32]

Heavy taxation, institutionalisation of land ownership, reforms, that weakened the privileged status of the Cambodian elite, as well as resentment against foreign domination, were the causes of intermittent rebellions that marked the colonial period. Revolts erupted in 1866, in 1870 and 1883/84 that attracted considerable support in the countryside, easily quelled by the French, who created discord among the Khmer forces. Sisowath, Norodom's half brother led his troops into combat alongside the French who nourished his ambitions for the royal crown.[33] Quelling the rebellion took one and one-half years, and it tied down some 4,000 French and Vietnamese troops that had been brought in from Cochinchina.

Ethnic Khmer colonial forces

[edit]The colonial military forces in Cambodia, tasked to quell potential insurrections, consisted of a light infantry battalion (Bataillon tirailleurs cambodgiens) and a national constabulary (Garde nationale, also called Garde indigène).[34]

The light infantry battalion, a Khmer unit with French officers, was part of a larger force, the third brigade, which had responsibility for Cambodia and for Cochinchina. In addition to the Cambodian battalion, the brigade was composed of French colonial and Vietnamese light infantry regiments and support elements. The brigade, headquartered in Saigon, was ultimately responsible to a supreme military command for Indochina located in Hanoi.

Under the French pre-World War II colonial regime, the constabulary consisted of a force of about 2,500 men and a mixed Franco–Khmer headquarters element of about forty to fifty officers, technicians, and support personnel. The force was divided into about fifteen companies deployed in the provinces. Control of the constabulary was vested in the colonial civil administration, but in times of crisis, command could pass quickly to military authorities in Saigon or in Hanoi. Service in the constabulary theoretically was voluntary, and personnel received a cash salary. Enlistments, however, were rarely sufficient to keep pace with personnel requirements, and villages occasionally were tasked to provide recruits.[35]

Japanese occupation (1941–1945)

[edit]

During World War II Japan which effectively controlled South-east Asia by 1942 tolerated the Vichy administration in Hanoi as a vassal of Nazi Germany that included permission of unhindered movement of Japanese troops through Indochina. The Japanese, while leaving the Vichy colonial government nominally in charge throughout Indochina, established an 8,000 troops strong garrison in Cambodia by August 1941.[36]

Thailand sought to take advantage of its alliance with Tokyo and colonial French weakness by launching an invasion of Cambodia's western provinces. As the French suffered a series of land defeats in the skirmishes that followed, a small French naval force intercepted a Thai battle fleet, en route to attack Saigon, and sank two battleships and other light craft. However, the Japanese then intervened and arranged a treaty, compelling the French to concede to Thailand the provinces of Battambang, Siem Reap and parts of Kampong Thom Province and Stung Treng Province. Cambodia lost one-third of its territory including half a million citizens.[37][38]

Cambodian nationalism assumed a more overt form in July 1942, when early leaders Pach Chhoeun, a monk named Hem Chieu and Son Ngoc Thanh organised resistance involving Cambodian military personnel. The plot was discovered by the colonial authorities that resulted in many injuries and in mass arrests.

On 9 March 1945, Japanese forces in Cambodia deposed the French colonial administration; and in an attempt get Khmer support for Tokyo's war, they encouraged Cambodia to proclaim independence. During this period the fate of the constabulary and of the light infantry battalion remained uncertain. The battalion apparently was demobilised, while the constabulary remained in place but was rendered ineffective, their French officers were interned by the Japanese. Japan had initially prepared for the creation of 5 Khmer volunteer units of 1,000 troops each to preserve public order and internal security. Recruitment of personnel for the volunteer units would include physical and written exams. Before the plan could be implemented the war ended and the concept died without further action.

At the conclusion of World War II a defeated Japanese military contingent waited to be disarmed and repatriated; French nationals sought to resume their pre-war rule with the support of Allied military units. The Khmer Issarak (nationalist insurgents with Thai backing), declared opposition to a French return to power, proclaimed a government-in-exile, and established a base in Battambang Province. On the eastern frontier Vietnamese communist forces (Việt Minh) infiltrated the Cambodian border provinces, organised a "Khmer People's Liberation Army" (not to be confused with the later Cambodian force, the Kampuchean People's National Liberation Armed Forces) and tried to forge a united front with the Khmer Issarak.[39]

First Indochina War (1945–54)

[edit]

In the fall of 1945 Prince Monireth proposed to raise an indigenous military force to the returning French authorities. Appointed defense minister, he announced the formation of the first native Cambodian battalion on 23 November and the establishment of an officer-candidate school on 1 January 1946. The Franco–Cambodian Modus Vivendi of 1946, mainly concerned political matters included recognition of the Cambodian army by French advisers in the Cambodian Ministry of Defense and the French authorities' responsibility for maintaining order.[40]

Facing increasing threats from thousands of Khmer Issarak combatants, regular troops quickly grew in numbers. In January 1947, the effective strength of the Cambodian military stood at about 4,000 personnel, of which 3,000 served in the constabulary who saw combat the same year. The remainder belonged to a mobile reserve of two battalion-sized units (one of the newly formed) named, respectively, the First Cambodian Rifle Battalion and the Second Cambodian Rifle Battalion (Bataillon de Chasseurs Cambodgiens). During the next two years, two more rifle battalions were added, bringing total strength up to 6,000 personnel, with about half serving in the Garde Nationale and half in the mobile reserve.[41][42]

By July 1949 Cambodian forces were granted autonomy within operational sectors beginning in the provinces of Siem Reap and Kampong Thom and in 1950 provincial governors received the assignment to oversee the pacification of their jurisdiction, supported by an independent infantry company. A military assistance agreement between the United States and France followed in the fall of 1950 determined the expansion of indigenous forces in Indochina, and by 1952 Cambodian troop strength had reached 13,000. Additional rifle battalions were formed, combat-support units were established, and a framework for logistical support was set up. Cambodian units were given wider responsibilities, such as border and coastal protection.

Prince Sihanouk seized power in June 1952, staging a "royal coup d'état" in 1953.[43] He suspended the constitution "to restore...order..." and took command of the army and operations. He attacked Son Ngoc Thanh's Khmer Issarak forces in Siem Reap Province and announced that he had driven "700 red guerrillas" across the border into Thailand.

In early 1953, Sihanouk embarked on a world tour to publicise his campaign for independence, contending that he could "checkmate communism by opposing it with the force of nationalism." Following his tour, he took control of entire Cambodia, joined by 30,000 Cambodian troops and police in a show of support and strength. Elsewhere, Cambodian troops under French officers staged slowdowns or refused the commands of their superiors, as a demonstration of solidarity with Sihanouk. Full independence was obtained in November 1953, and Sihanouk took command of the army of 17,000 troops, which had been renamed the Royal Cambodian Armed Forces (Forces armées royales khmères – FARK).

In March 1954, combined Viet Minh and Khmer Issarak forces launched attacks from Vietnam into northeastern Cambodia. Conscription was introduced for men between fifteen and thirty-five years of age and national mobilisation was declared. Following the conclusion of the Geneva Conference on Indochina in July, Viet Minh representatives agreed to withdraw their troops from Cambodia. FARK troop numbers of 47,000 dropped to 36,000, with demobilisation after Geneva at which it was to be maintained for the next fifteen years except during periods of emergency.[44]

Second Indochina War (1954–75)

[edit]

In 1955, the United States and Cambodia signed an agreement providing for security assistance. In addition to a Military Assistance Advisory Group (MAAG) and military budget support, FARK received US supplies and equipment worth approximately US$83.7 million for eight years until the assistance program was discontinued at Sihanouk's request in 1963. France also retained a military training mission in Cambodia until 1971 from which FARK military traditions and doctrines were adopted.[45]

As the United States failed to guarantee a reliable military support program Sihanouk increasingly pursued a neutralist foreign policy during the 1960s and eventually declared that Cambodia would "abstain from military or ideological alliances" but would retain the right to self-defense.[46]

From 1958 on Northern and Southern Vietnamese combat troops began to violate Cambodian territory on a regular basis. Neither Washington nor Hanoi responded to Sihanouk's protests, which lead him to establish diplomatic relations with China. By the mid-1960s, large areas within Cambodia served as supply routes and strategic staging sites for North - and South Vietnamese communists and Viet Cong forces. FARK could do little more than monitor these developments and maintained a modus vivendi with the intruders as Sihanouk charged the United States of complicity with the Khmer Serei, which further strained Cambodian–American relations.[45]

Economic and military cooperation with the United States was formally terminated on 3 May 1965. Although French military assistance and training continued until 1972, Sihanouk began to accept military assistance from the Soviet Union. He also accused Thailand and South Vietnam of subversive cooperation with the USA whom he suspected to actively destabilize his government and promote the Khmer Serei.[47][45][48]

By the mid-1960s Cambodia's armed forces had failed to incorporate into a comprehensive program of one of the opposing sides of the cold war. Mixed military equipment of several suppliers with varying doctrines and structure worsened FARK's strategic position.[45]

Unable to effectively combat Vietnamese presence in Eastern Cambodia Sihanouk, in a gesture of appeasement secretly offered the deep-water port of Sihanoukville, situated at the Gulf of Thailand as a supply terminal for the NVA. FARK's role as a centrally lead operative force eroded further and increasingly functioned as a highly corrupt arbiter of uncontrolled weapon deals and as shipment agency.[45][49]

In 1967 FARK brutally suppressed the Samlaut Uprising of frustrated peasants in Battambang Province who, among other things, protested against government price dumping for rice, treatment by local military, land displacement and poor socio-economic conditions. Sihanouk attributed the insurrection to the Khmer Rouge and blamed the "Thai patriotic front" to have been the instigating force in the background. Sihanouk's incorrect political analysis and the inappropriate actions of FARK against civilians caused a serious alienation process between Cambodia's population and the official armed forces. Many people fled FARK's repressions and joined rebel groups of whom the Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea became the most prolific. As long as Sihanouk remained in power these forces received very limited military assistance from Hanoi because this might have alienated Sihanouk's government and affected North Vietnamese and Viet Cong access to Cambodian territory and the Sihanoukville supply route.[45]

The 1969 U.S. bombing campaigns inside Cambodian territory caused the Vietnamese to penetrate deeper into the country where they came into more frequent hostile contact with FARK, who reportedly conducted joint operations with South Vietnamese forces against the North Vietnamese and the Viet Cong. Sihanouk disapproved of these latest communist incursions, terminated access to Sihanoukville's port and stated that "to deal with the Viet Cong and Viet Minh", he is going "to give up the defensive spirit and adopt an offensive spirit." On 11 June 1969 he announced that "...at present there is war in Ratanakiri Province between Cambodia and Vietnam."[45]

In January 1970 a group of FARK officers under general Lon Nol exploited Sihanouk's absence to carry out a coup d'État that was confirmed by the National Assembly of Cambodia two months later. The coup passed without any violent incidents and all FARK contingents, around 35,000 to 40,000 troops, organised mainly as ground forces remained alert, manned and secured key strategic positions.[45]

The FARK were renamed to Khmer National Armed Forces (Forces armées nationales khmères - FANK) under Lon Nol's command. His government reiterated a neutral political stance. However, attempts to negotiate a peaceful withdrawal of the Vietnamese from Cambodian territory were rejected. As a consequence, Lon Nol called for UN intervention and international assistance.[45]

From 29 April and 1 May 1970, South Vietnamese and United States ground forces entered eastern Cambodia and captured vast quantities of enemy matériel, destroyed NVA and Viet Cong infrastructure and depots. Retreating Vietnamese troops pushed further west into Cambodia, destroyed FANK troops and positions, seriously destabilizing the Lon Nol government. After South Vietnamese and United States army withdrawal all of north-eastern Cambodia was controlled by the Vietnamese, who extensively supported, equipped local communist Khmer Rouge insurgents that had replaced FANK in these territories.[50]

A comprehensive assessment of the Khmer Republic's armed forces revealed serious shortcomings, such as the "lack of combat experience, equipment deficiencies,...lack of mobility" and "incompetent and corrupt officers". Although martial law was declared and total mobilization introduced, reliable and transparent administration, replacement of incompetent and corrupt officers, important personnel and educational reforms based on a modern military doctrine did not take place.

FANK strategy focused on securing the central territory. The majority of the population occupied these rich, rice-growing areas as Vietnamese and Khmer Rouge control constituted the forested and mountainous lands north and east of the "Lon Nol Line." Two military offensives (Chenla I, in August 1970, and Chenla II, in August 1971) were undertaken in order to regain control of the fertile agricultural area of Kompong Thom north of Phnom Penh. Some initial success was not exploited and FANK was eventually defeated by the opposing North Vietnamese Ninth Division and increasingly numerous and effective Khmer Rouge divisions. These troops had acquired considerable political momentum since the dethroned Sihanouk served as their new figurehead proclaiming war of national liberation.

In 1970 Sihanouk announced the establishment of the Royal Government of National Union of Kampuchea (Gouvernement royal d'union nationale du Kampuchéa – GRUNK), which he claimed was legitimized by the National United Front of Kampuchea (Front uni national du Kampuchéa – FUNK). This rhetoric was particularly popular among the rural population and ethnic minorities.[51] The RAK (Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea) was renamed the Cambodian People's National Liberation Armed Forces (CPNLAF).[52]

By 1972 FANK actions were mainly defensive operations for steadily shrinking government territory which by November 1972 had reached a point that required a new strategic realignment of the Lon Nol line. Lost were the rich rice-growing areas around the Tonlé Sap lake. The remaining territory still held the majority of the population. It consisted of south-eastern Cambodia - roughly a triangle from Phnom Penh in the north via Sihanoukville in the south to the Vietnamese border in the east. By 1973 the CPNLAF controlled about 60 percent of the country's territory and 25 percent of the population.[53]

CPNLAF began its offensive on Phnom Penh at New Year 1975 - by then the last remnant of Khmer Republic territory. Khmer Rouge forces slowly encircled the city as all roads and riverine routes were cut. By early April most defensive positions had been overrun with FANK units annihilated and supplies exhausted. On 17 April the Khmer Republic fell and FANK was totally crushed, beaten by a disciplined enemy army in a conventional war of movement and manoeuvre.[50]

Cambodian Civil War

[edit]Military developments under the Khmer Rouge

[edit]

The 68,000 troops of Democratic Kampuchea were led by a small group of intellectuals, inspired by Mao Zedong’s Cultural Revolution in China who aimed to convert Cambodia into an agrarian Utopia. With help from the Vietnamese, indoctrinated and highly dedicated to Maoist communist ideology, a handful of loose companies, recruited from peasantry developed into disciplined forces, trained in guerrilla warfare as well as in modern manoeuvre warfare. When North Vietnamese combat divisions had withdrawn from Cambodia by the end of 1972 these forces defeated FANK - the regular army of Cambodia on their own within 2 years.[54][50]

In 1975 that marked the beginning of Democratic Kampuchea, the CPNLAF (Cambodian People's National Liberation Armed Forces) were renamed RAK (Revolutionary Army of Kampuchea) once again. Led by long-time commander and then Minister of Defense Son Sen, RAK consisted of 230 battalions in 35 to 40 regiments in 12 to 14 brigades. The command structure in units was firmly based on an extreme form of peasant communist ideology with three-person committees where the political commissar ranked highest. The country was divided into military zones and special sectors, the boundaries of which changed slightly over the years. One of RAK's first tasks upon military and political consolidation, was the wholesale and summary execution of former FANK officers and governments officials and their families.[55]

The Khmers Rouge units were led by secretaries of the various military zones who exerted supreme political and military power. A national army was established in order to enforce discipline and to separate formerly autonomously operating forces as troops from one zone frequently were sent to another. These efforts were considered to be essential by the central governing group as to control regional secretaries and their dissident or ideologically impure cadres. A practice that eventually culminated in widespread bloody purges decimating the ranks, undermined the morale and considerably contributed to the rapid collapse of the regime. As author Elizabeth Becker noted, "in the end paranoia, not enemies, was responsible for bringing down the regime."[56]

Cambodian–Vietnamese border tensions

[edit]

Tensions between Cambodia and Vietnam have been going on for hundreds of years.[57] They first peaked during the 19th century when only the establishment of the French Protectorate of Cambodia prevented the inevitable incorporation into a Vietnamese empire. French colonial administrators established numerous administrative zones and borders such as the Brévié Line, with little regard to historic and ethnic considerations. Virtually all of these re-drawings resulted in territorial gains for Vietnam, who since independence after 1945 refuse to re-negotiate with Cambodia referring to the authority of the colonial calibrations.[53]

First clashes between the RAK and Vietnam's NVA date back to 1970, as Khmer Rouge units fired on North Vietnamese troops. Reports of engagements of growing intensity continued, particularly after 1973. The North Vietnamese initially chose to ignore the incidents because they regarded the sanctuaries in Cambodia as vital for their domestic war. After the communist victories of April and May 1975, Khmer Rouge border raids increased, that included massacres of villagers. Democratic Kampuchea attempts to capture several disputed insular territories in the Gulf of Thailand (e.g. Thổ Chu and Phú Quốc[58]) ended, apart from high civilian losses, in failure.

Deteriorating Cambodia–Vietnam relations reached a low on 31 December 1977 as Radio Phnom Penh reports a "ferocious and barbarous aggression launched by the 90,000 [troops of the] Vietnamese aggressor forces against Democratic Kampuchea", denounced the "so-called Socialist Republic of Vietnam" and announced a "temporary severance" of diplomatic relations. Escalating rhetoric border skirmishes erupted into pitched battles in the summer and the fall of 1978. Major engagements were reported from Svay Rieng Province, Kampong Cham Province and Ratanakiri Province.

In November 1978 Vietnamese forces launched a sustained operation on Cambodian soil in the area of the town of Snuol and Memot in Kratié Province. This action cleared a liberated zone where anti-Khmer Rouge Cambodians could launch a broad-based political movement that opposed the inhumane Pol Pot regime. On 2 December 1978 the Kampuchean National United Front for National Salvation - KNUFNS was proclaimed in a rubber tree plantation amid rigid security provided by heavily armed Vietnamese units reinforced with anti-aircraft guns.

Vietnamese invasion of Cambodia

[edit]

The establishment of KNUFNS made a forceful removal of Democratic Kampuchea inevitable. However, KNUFNS was by no means an effective force. Only Vietnam's NVA, which had already had deployed a task force beyond the border, was capable of successfully completing such an operation.[59]

Twelve to fourteen divisions and three Khmer regiments - the future nucleus of KPRAF - launched an offensive on 25 December 1978, with a total invasion force comprising some 100,000 troops. NVA forces first headed towards Kratié City and Stung Treng City; however, this initial move was conducted to conceal their final strategic objectives: to secure a far-reaching Vietnamese base in the large but sparsely occupied North-Eastern territories, and to prevent any Khmer Rouge units from retreating into this area.

The Khmer Rouge concentrated defensive units only in the plains regions of eastern and south-eastern Cambodia, where they correctly anticipated the main focus of NVA attacks. Strong Vietnamese forces rushed in three columns towards the Kampong Cham river port, the Mekong river crossing at Neak Loeung, and along the gulf coast in order to capture the sea ports of Sihanoukville and Kampot.

The morale and combat effectiveness of the Democratic Kampuchea troops had considerably deteriorated, and many senior commanders had been lost in party purges. Serious battle engagements were confined to small areas as most Khmer Rouge units – under relentless NVA artillery and air force assaults – soon retreated west. The first Vietnamese troops reached the eastern banks of the Mekong near Phnom Penh on 5 January 1979. Whether it was Hanoi's initial intention to go any further is still not entirely clear. However, after a 48-hour halt to regroup and rout Khmer Rouge troops, the assault on Phnom Penh was launched, and the undefended and deserted city was captured on 7 January 1979.[60]

With the capital secure, NVA units proceeded towards and captured Battambang and Siem Reap in western Cambodia. Prolonged and serious fighting took place west of Sisophon near the Thai border, lasting until April. The last Khmer Rouge fighters evacuated into the remote forests on both sides of the border. Vietnamese troops did not advance further and kept a distance to Thai territory. As international dissent over the legitimacy of the new government persisted, the Khmer Rouge continued to threaten and attack inner Cambodia for more than another decade, seeking to reclaim political power.

Following the Vietnamese intervention, two anti-Vietnamese non-communist political and military fronts emerged from the masses of civilian refugees and dislodged soldiery - namely the Khmer People's National Liberation Armed Forces (KPNLAF)[61] and the Sihanouk National Army (Armée nationale sihanoukiste – ANS, see also: FUNCINPEC).[62] During the next decade, both factions operated independently from bases inside Thai territory, conducting hit-and-run insurgency operations against Vietnamese troops and the current government, who failed to neutralize the threat. The Vietnamese and the People's Republic of Kampuchea government's K5 Plan[63] (also known as the Bamboo Curtain) established trenches, wired fences, and extensive minefields along the 700 km (430 mi) border with Thailand. The K5 Plan further destabilized the region and increased chaos, as maintenance and effective patrolling became ever more difficult, while rebel forces eventually succeeded in avoiding or crossing it.[64][59]

Military developments in postwar Cambodia

[edit]Military stalemate

[edit]As the 1980s proceeded Vietnam maintained a permanent 140,000 strong force, supplemented by 30,000 to 35,000 KPRAF troops. This force managed to continuously control the Cambodian heartlands, including the commercial, agricultural and population centres. The opposing rebel factions had established a government in exile known as the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea (CGDK), encouraged by widespread international rejection (in particular by the Association of Southeast Asian Nations - ASEAN) of Vietnamese authority. However, attempts at political and military co-operation, like the Permanent Military Coordinating Committee of 1984 and the subsequent Joint Military Command, failed due to ideological differences and general mistrust.[65] Factional uncoordinated military actions prevented strategic gains and only affected the fringes of Battambang, Siem Reap and Oddar Meanchey provinces. The two opposing fronts had drifted into a stalemate, unable to defeat or weaken each other and only further obstructing vital political progress.[66] Soon after one of the rare CGDK tactical co-operations that involved all three factions in 1986, the Khmer Rouge quickly resumed hostilities towards the two non-communist factions and "repeatedly ambushed and killed troops." Prince Sihanouk, figurehead and chief negotiator among the three CGDK factions, resigned in 1987.[67]

CGDK factions

[edit]National Army of Democratic Kampuchea

[edit]In December 1979, the Khmer Rouge renamed their army to the National Army of Democratic Kampuchea (NADK), followed by political reorganisation and the demotion of Pol Pot to an advisor in 1985. These reforms were adopted as an attempt to diassociate themselves from the terror of the Pol Pot era. NADK forces consisted of former RAK troops, conscripts forcibly recruited during the 1978/79 retreat, and personnel pressed into service during in-country raids or drawn from refugees and new volunteers. Military observers and journalists estimated around 40,000 and 50,000 NADK combatants, which were considered to be "the only effective [anti-Vietnamese] fighting force".

In 1987 the opinion that the NADK was "the only effective fighting force" opposing the Vietnamese was expressed by foreign observers. In an interview published in the United States in May 1987, Sihanouk reportedly said, "without the Khmer Rouge, we have no credibility on the battlefield... [they are]... the only credible military force." Led by senior figures such as Son Sen, Khieu Samphan, Ieng Sary and Ta Mok with an unclear hierarchy and loyalty structure, the NADK units were "less experienced, less motivated, and younger" than the early to mid 1970s generation of Khmer Rouge fighters. The NADK only gained limited success, despite their use of terror against civilians, murder and destruction of property and economic resources, and invoking traditional Cambodian hatred of the Vietnamese as a means to recruit personnel; most Cambodians preferred to live under Vietnamese occupation rather than endure another Khmer Rouge reign.

The NADK divided Cambodia into four autonomous military zones. As the bulk of combatants were stationed at the Thai border, countless Khmer Rouge sanctuaries existed countrywide. This kept Cambodia "in a permanent state of insecurity" until the late 1990s. The NADK received most of its military equipment and financing from China. Sources suggest Chinese aid in between US$60 Million and US$100 Million a year, to as high as US$1 million a month, arrived via two infiltration routes. One of them ran south from Thailand through the Dangrek Mountains into northern Cambodia. The second ran north from Trat, a Thai seaport in the Gulf of Thailand.

Khmer People's National Liberation Armed Forces

[edit]

The Khmer People's National Liberation Armed Forces (KPNLAF) was the military component of the Khmer People's National Liberation Front (KPNLF). The KPNLAF was formed in March 1979 and loyal to Son Sann. It was consolidated by General Dien Del (Chief of Staff) from various anticommunist groups, former Khmer Republic soldiers, refugees, and retreating military and insurgency combatants at the Thai border. The KPNLAF initially lacked a central command structure, as personal allegiance and loyalty only functioned in various warlord bands. These bands focused on trading all kinds of commodities and fighting rival factions, rather than on conducting combat operations. However, as the KPNLAF opposed all communist factions, it constituted the second largest guerrilla force. By 1981, with about 7,000 men under arms, it was able to protect its border camps and conduct occasional forays further inland.

Beginning in 1986 the KPNLAF declined as a fighting force as it lost its bases at the Thai–Cambodian border, following the Vietnamese dry season offensive of 1984/85. Inflexible and unable to adapt to new conditions, combatants were "virtually immobilized by the loss of their camps." Additionally, senior commanders began to oppose the "dictatorial ways" of president Son Sann, who regularly interfered into "military matters". Units deserted or demobilized in order to await the outcome of leadership clashes; this led to the collapse of the central chain of command, and stagnation and collapse of the entire KPNLAF structure.

1987 estimates of KPNLAF unit strength varied within a maximum total of 14,000 troops. The KPNLAF divided Cambodia into nine military regions or operational zones, and was headed by a general officer (in 1987, by General Sak Sutsakhan) who functioned as commander in chief, a chief of staff, and four deputy chiefs of staff in charge of military operations, general administration, logistical affairs, and planning/psychological operations respectively. Combat units were divided into battalions, regiments, and brigades. The KPNLAF received most of its military equipment from China. However, further aid and training was granted by ASEAN nations such as Singapore and Malaysia.[68]

Armée Nationale Sihanoukiste

[edit]The Armée National Sihanoukiste (ANS) constituted the armed component of FUNCINPEC, royalist supporters of Sihanouk also based at the Thai border, and was smaller than the KPRAF. It was founded in June 1981 as a merger of the Movement for the National Liberation of Kampuchea (Mouvement pour la libération nationale du Kampuchea – MOULINAKA) and several minor armed groups. The ANS only began to develop a professional and effective military structure with the formation of the Coalition Government of Democratic Kampuchea, which introduced international shipments of supplies and armaments (mostly Chinese equipment). By 1986/87, the ANS had replaced the KPNLAF (weakened by leadership dispute) as the primary non-communist rebel force.

Figures of ANS personnel strength during the 1980s are based on the statements of Sihanouk and his son Prince Norodom Ranariddh (since 1987 commander in chief and chief of staff), ranging from 7,000 to a maximum of 11,000 combatants, plus an additional "8,500 fighters permanently inside Cambodia.". Major General Prince Norodom Chakrapong functioned as deputy chief of staff. Combat and manoeuvre elements consisted of battalions grouped under six brigades, four additional independent regiments (at least one composed of Khmer Rouge deserters), and a further five independent commando groups.

Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Armed Forces

[edit]The Kampuchean People's Revolutionary Armed Forces (KPRAF) constituted the regular armed forces of the People's Republic of Kampuchea (PRK) under Vietnamese occupation. It was promoted and supervised by Hanoi and established immediately after the fall of the Khmer Rouge in order to sanitize the regime's image ruling a legitimate and sovereign state. Furthermore, the People's Army of Vietnam (PAVN) would require an effective Khmer military force that eventually could replace NVA units in future security tasks. The establishment of a sovereign ethnic Khmer army also addressed the problem of traditional fears and widespread hate towards the Vietnamese among the population, and was instrumental for the upkeep of public order. However, it remained a very delicate matter, as several recent precedents had seriously affected Cambodia's fortunes, such as supporting Khmer communist factions and raising regiments of Khmer troops for the Vietnamese invasion. Nonetheless, the KPRAF consolidated as the official military force and served as an instrument of both the party and the state. These measures remained classified, and much that could be concluded about the armed forces of the PRK was based on analysis rather than incontrovertible hard data.

Foreign armed forces

[edit]As many as 200,000 troops invaded Cambodia in 1978. Designated by Hanoi as "The Vietnamese volunteer army in Kampuchea", the PAVN force, comprising some ten to twelve divisions, was made up of conscripts who supported a "regime of military administration." After several years, Vietnam ostensibly began to decrease the size of its military contingent in Cambodia. In June 1981, Vietnam's 137th Division returned home. In July 1982, Hanoi announced it would withdraw an unspecified number of troops as these withdrawals became annual occurrences with elaborate departure ceremonies. However, critical observers contended that these movements were merely troop rotations.[60]

Hanoi publicly committed itself to withdraw its occupation forces by 1990. It first announced this decision following an August 1985 meeting of Vietnamese, Laotian, and Cambodian foreign ministers. The commitment to a pullout engendered continuing discussion, both by foreign observers and by Indochinese participants. What emerged was the clarifying qualification that a total Vietnamese military withdrawal was contingent upon the progress of pacification in Cambodia and upon the ability of the KPRAF to contain the insurgent threat without Vietnamese assistance. Prime Minister Hun Sen declared in a May 1987 interview that "if the situation evolves as is, we are hopeful that by 1990 all Vietnamese troops will be withdrawn ... [but] if the troop withdrawal will be taken advantage of, we will have to negotiate to take appropriate measures...." Shortly thereafter, a KPRAF battalion commander told a Phnom Penh press conference that "Vietnamese forces could remain in Cambodia beyond 1990, if the Khmer Rouge resistance continues to pose a threat." In an interview with a Western correspondent, Vietnamese Foreign Minister Nguyen Co Thach repeated the 1990 withdrawal pledge, insisting that only foreign military intervention could convince Hanoi to change its plans. Some ASEAN and Western observers greeted declarations of a total pullout by 1990 with incredulity. Departing Vietnamese units reportedly left equipment behind in Cambodia, and it was suggested that they easily could return if it looked as though a province might be lost.

Vietnam's presence in Cambodia reportedly consumed 40 to 50 percent of Hanoi's military budget. Although substantial portions of the cost had been underwritten by Soviet grant aid, Vietnamese troops in Cambodia apparently were on short rations. Radio Hanoi reportedly commented on troops "dressed in rags, puritanically fed, and mostly disease ridden." The parlous state of Vietnamese forces in Cambodia also was the subject of a report by the director of an Hanoi military medical institute. According to media accounts, the report acknowledged that Vietnamese troops in the country suffered from widespread and serious malnutrition and that beriberi occurred in epidemic proportions.

Vietnamese military advisers also were detached to serve with KPRAF main and provincial forces down to the battalion, and perhaps even the company, level. The functions and the chain of command of these advisers remained unknown, except that it could be assumed that they reported to the Vietnamese military region or front headquarters.

21st century military structure

[edit]As a member of ASEAN's defensive program, Cambodia's army has adopted modern military doctrines which call for developing practical co-operation in a regional defense concept.[69] All common branches of military service are maintained and equipped accordingly. Personnel and recruitment figures are centrally administered and published annually. Active combat forces are supported by reserve troops.[70]

References

[edit]- ^ "Archaeological evidence of warfare and weaponry at Phum Snay". Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ John N. Miksic (30 September 2013). Singapore and the Silk Road of the Sea. NUS Press. ISBN 9789971695583. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Lavy, Paul A. (2003). "As in Heaven, So on Earth: The Politics of Visnu Siva and Harihara Images in Preangkorian Khmer Civilisation". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 34 (1). academia edu: 21–39. doi:10.1017/S002246340300002X. S2CID 154819912. Retrieved 23 December 2015.

- ^ a b c John Norman Miksic (14 October 2016). Ancient Southeast Asia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 9781317279044. Retrieved 1 January 2018.

- ^ "Two Historical Records of the Kingdom of Vientiane - That was probably also the reason for the Cambodian conquests in Champa in the reigns of the Angkor kings Suryavarman II and Jayavarman VII" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 30 June 2015.

- ^ a b Woolf, D. R. (3 June 2014). A Global Encyclopedia of Historical Writing, Volume 2 - Tiounn Chronicle. Routledge. ISBN 9781134819980. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ^ "March to the South (Nam Tiến)". Khmers Kampuchea-Krom Federation. Archived from the original on 26 June 2015. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ Chapuis, Oscar (1 January 2000). The Last Emperors of Vietnam: From Tu Duc to Bao Dai. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 48. ISBN 9780313311703. Retrieved 3 April 2015.

- ^ "The French in Cambodia: Years of revolt (1884 - 1886)". Phnom Penh Post. 11 December 1998. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Stuart-Fox, Martin (1997). A History of Laos. Cambridge University Press. pp. 24–25. ISBN 0-521-59746-3.

- ^ Geoffrey Gunn. "The Great Vietnamese Famine of 1944-45 Revisited". The Asia-Pacific Journal. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Conflict in Cambodia, 1945-2002 by Ben Kiernan - American aircraft dropped over half a million tons of bombs on Cambodia's countryside, killing over 100.000 peasants..." (PDF). Yale University. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ "COMMUNISM AND CAMBODIA - Cambodia first declared independence from the French while occupied by the Japanese. Sihanouk, then King, made the declaration on 12 March 1945, three days after Hirohito's Imperial Army seized and disarmed wavering French garrisons throughout Indo-China" (PDF). DIRECTORATE OF INTELLIGENCE. Retrieved 7 July 2015.

- ^ Buckley, H. R.; O'Reilly, D. J. W.; Domett, K. M. (2 January 2015). "Bioarchaeological evidence for conflict in Iron Age north-west Cambodia - Examination of skeletal material from graves at Phum Snay". Antiquity. 85 (328). Cambridge University Press: 441–458. doi:10.1017/S0003598X00067867.

- ^ Peter N. Peregrine (31 January 2001). Encyclopedia of Prehistory: Volume 3: East Asia and Oceania. Springer. ISBN 9780306462573. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Glover, Ian (2004). Southeast Asia: From Prehistory to History. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-29777-6.

- ^ J. Stephen Hoadley (5 September 2017). Soldiers and Politics in Southeast Asia: Civil-Military Relations in ... Routledge. ISBN 9781351488822. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ Rodrigo Quijada Plubins (12 March 2013). "Khmer Empire". World History Encyclopedia. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "Angkor Wat: equated with the quintessence of Cambodian culture for more than a century - The Cham fleet sailed up the Mekong River...The reaction was very quick..." The Phnom Penh Post. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 21 June 2015.

- ^ "Bayon: New Perspectives Reconsidered Michael Vickery" (PDF). Michael Vickery’s Publications. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Siam Society Books - The Royal Chronicles of Ayutthaya - A Synoptic Translation by Richard D. Cushman". Siam Society. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Cambodia's cultural heritage considerations in Area Studies by Aratoi Hisao". googleusercontent.com. Retrieved 12 March 2015.

- ^ "Essay on Cambodian History from the middle of the 14 th to the beginning of the 16 th Centuries According to the Cambodian Royal Chronicles by NHIM Sotheavin - So far, the reconstruction of history from the middle of the 14 th to the beginning of the 16 th centuries is locked in a sort of unsolved state, since local sources prove inadequate and references from foreign sources are of little use" (PDF). Sophia Asia Center. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 April 2015. Retrieved 1 July 2015.

- ^ Bourdonneau, Eric (September 2004). "Culturalism and historiography of ancient Cambodia: about prioritizing sources of Khmer history - Ranking Historical Sources and the Culturalist Approach in the Historiography of Ancient Cambodia by Eric Bourdonneau - 29 Also this material is sparse..." Moussons. Recherche en Sciences Humaines Sur l'Asie du Sud-Est (7). Presses Universitaires de Provence: 39–70. doi:10.4000/moussons.2469. Retrieved 3 July 2015.

- ^ "The historical Records of Ayudhya...Blamed on the invasion of Pagan in 1767, all Ayudhya's past records were assumed perished during its fall to the Burmese attack". Khmer heritage. 31 May 2015. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Angkor Wat: equated with the quintessence of Cambodian culture for more than a century - Behind the mythical towers: Cambodian history". Phnom Penh Post. 14 June 2013. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "A king and a stone - Nineteenth century or twelfth? When the Thai script was first inscribed has much to do with how history is used politically by Rahul Goswami". Khaleej Times. 29 November 2014. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "Recreations epigraphic (2 2). Epigraphic western: the case of Ramkhamhaeng by Jean-Michel Filippi". Kampotmuseum. 28 June 2012. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "THE ABRIDGED ROYAL CHRONICLE OF AYUDHYA - In 712 of the Era, Year of the Tiger..." (PDF). The Siam Society. Retrieved 12 June 2015.

- ^ "History of Ayutthaya - Dynasties - King Ramesuan". History of Ayutthaya. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ^ "London Company's Envoys Plot Siam" (PDF). Siamese Heritage. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Volume IV - Age of Revolution and Empire 1750 to 1900 - French Indochina by Justin Corfield" (PDF). Grodno State Medical University. Retrieved 24 January 2017.

- ^ "Cambodia - Tai and Vietnamese hegemony". britannica.com. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Archive & 1re Guerre mondiale : Quand les Cambodgiens se battaient pour la France" (in French). Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ "Cambodia The French Protectorate, 1863-1954". photius. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Arthur J. Dommen (20 February 2002). The Indochinese Experience of the French and the Americans: Nationalism and ... Indiana University Press. ISBN 0253109256. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Dr. Andrew McGregor. "Vichy versus Asia: The Franco-Siamese War of 1941". WWII Forum. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Pierre Gosa (2008). Le conflit franco-thaïlandais de 1940-41: la victoire de Koh-Chang. Nouvelles Editions Latines. ISBN 9782723320726. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

- ^ Murashima, Eiji (1 November 2005). "Opposing French colonialism Thailand and the independence movements in Indo-China in the early 1940s". South East Asia Research. 13 (3): 333–383. doi:10.5367/000000005775179702. S2CID 147391206.

- ^ David P. Chandler (1991). The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. GoogleBooks. p. 22. ISBN 0300057520. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

Prince Monireth.

- ^ David P. Chandler (1991). The Tragedy of Cambodian History: Politics, War, and Revolution Since 1945. Yale University Press. p. 43. ISBN 0300057520. Retrieved 13 January 2018.

Franco–Khmer headquarters.

- ^ Grant, Edited by Jonathan S.; Moss, Laurence A. G.; Unger, Jonathan (1971). Cambodia: the widening war in Indochina. New York: Washington Square Press. p. 314. ISBN 0671481142.

{{cite book}}:|first1=has generic name (help) - ^ "Cambodia Under Sihanouk - 1949-1970". Globalsecurity. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ "First Indochina War - Cambodia". Britannica. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "Cambodian The Second Indochina War, 1954-75". Country-data. Retrieved 14 January 2018.

- ^ William S. Turley (17 October 2008). The Second Indochina War: A Concise Political and Military History. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. ISBN 9780742557451. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ William J. Rust (2016). 9 "Stupid Moves" (1959–1960) Eisenhower and Cambodia: Diplomacy, Covert Action, and the Origins of the Second Indochina War. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 9780813167459. JSTOR j.ctt1bqzmsw.

- ^ William J. Rust (24 June 2016). "Covert Action in Cambodia". University Press of Kentucky. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "America's Vietnam War in Indochina War in Cambodia". US History. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b c Melvin Gurtov. "Indochina in North Vietnamese Strategy" (PDF). RAND Corporation. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Zal Karkaria. "Failure Through Neglect: The Women's Policies of the Khmer Rouge in Comparative Perspective" (PDF). Concordia University Department of History. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ Arnold R. Isaacs (27 January 1999). Without Honor: Defeat in Vietnam and Cambodia. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801861079. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b "Khmer Rouge History". Cambodia Tribunal. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Precursors to Genocide: Rise of the Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot". United to End Genocide. 6 April 2016. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "The Khmer Rouge and Pol Pot's Regime". Mount Holyoke College. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "VIETNAM, CAMBODIA AND THE US" (PDF). Repository Library Georgetown. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "Reconceptualizing Southern Vietnamese History from the 15th to 18th Centuries Competition along the Coasts from Guangdong to Cambodia by Brian A. Zottoli". University of Michigan. Retrieved 26 June 2015.

- ^ "Island map of Cambodia". Island Wild Life Cambodia. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b "1978-1979 - Vietnamese Invasion of Cambodia". GlobalSecurity. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ a b Kevin Doyle (14 September 2014). "Vietnam's forgotten Cambodian war". BBC. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East ..., Volume 1. Bloomsbury Academic. ISBN 9781576077702. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ "The non-communist factions in Cambodia" (PDF). CIA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Esmeralda Luciolli, Le mur de bambou, ou le Cambodge après Pol Pot. (in French)

- ^ Kelvin Rowley. "Second Life, Second Death: The Khmer Rouge After 1978" (PDF). Swinburne University of Technology. Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Boraden Nhem (28 July 2017). The Chronicle of a People's War: The Military and Strategic History of the ... Routledge. ISBN 9781351807654. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Bertil Lintner (31 October 2007). "Odd couple: The royal and the Red". Asia Times Online. Archived from the original on 23 July 2008. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ^ Sorpong Peou (12 July 2017). Cambodia: Change and Continuity in Contemporary Politics: Change and ... Routledge. ISBN 9781351756501. Retrieved 9 March 2018.

- ^ Ted Galen Carpenter (24 June 1986). "U.S. Aid to Anti-Communist Rebels: The "Reagan Doctrine" and Its Pitfalls - Cambodia" (PDF). Cato Institute. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ^ "ASEAN DEFENCE MINISTERS' MEETING (ADMM) - THREE-YEAR-WORK PROGRAM - 2011-2013" (PDF). ASEAN org. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- ^ "2017 Cambodia Military Strength - Current military capabilities and available firepower for the nation of Cambodia". Global Firepower. Retrieved 10 March 2018.

- Tatu, Frank. "National security". Cambodia: A Country Study (Russell R. Ross, editor). Library of Congress Federal Research Division (December 1987). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.[1]