Maude Hutchins

Maude Phelps McVeigh Hutchins | |

|---|---|

| Born | February 4, 1899 Guilford, New York, U.S. |

| Died | March 28, 1991 Fairfield, Connecticut, U.S. |

| Occupation | Artist • Author |

| Language | English |

| Education | Yale University |

| Notable works | Victorine (1959) |

| Spouse | Robert Maynard Hutchins |

Maude Hutchins (4 Feb 1899 – 28 March 1991) was an American artist, sculptor, and novelist from New York.

Early life and education[edit]

Maude Hutchins was born Maude Phelps McVeigh on February 4, 1899, in Guilford, New York.[1] She was the daughter of Warren Ratcliff McVeigh, an editor at the New York Sun, and Maude Louise Phelps.[2] She had an older sister, Frances Ratcliffe McVeigh.

Maude and her sister were orphaned at a young age and lived with their grandparents in Bayshore on Long Island. Also living with them was their wealthy aunt, Carlonia Thompson (a prominent member of Long Island society), and her husband and children.[2][3] By 1920, Maude was living solely with her aunt and one of her cousins.[4]

On September 10, 1921, Maude married Robert Maynard Hutchins, who went on to become University of Chicago president.[5][6] Previously, Mr. Hutchins was on the faculty of Yale University which is how he met Maude.[7]

Maude attended St. Margaret's School in Waterbury, Connecticut and then received her B.F.A from the Yale School of Fine Arts,[8] completing her five-year degree in only three and a half. She won several awards, including the Warren Whitney Memorial Prize for heroic figure at the Beaux Arts in New York. She graduated in 1926, but remained at Yale for two years after, during which time she executed a number of portraits and did other professional work.[9]

Career[edit]

Hutchins became a professional artist in 1924. She had her first art show at the Cosmopolitan Club in New York City. A drawing from her 1932 work, Diagrammatics, which she co-published with Mortimer J. Adler, was enlarged and displayed as a mural in the Hall of Science at the Century of Progress Exhibition in Chicago, Illinois.[2]

She exhibited also at the New Haven Paint and Clay Club, became a member of the National Association of Women Painters and Sculptors and showed with that organization in New York. Her artwork was included in many exhibitions at such places as the Brooklyn Museum, Minneapolis Museum, the San Francisco Museum of Art, the Wisconsin Union, the Renaissance Society, the St. Louis Museum, and annual shows at the Chester Johnson-Dell Quest Galleries.[9]

Despite Maude's talent for art and her duties to her three children, she felt the urge to write. She began publishing short stories poems and plays-for-reading in various literary magazines like the New Yorker, the Kenyon Review, Accent, Mademoiselle, Nation, Epoch, Poetry, and the Quarterly Review of Literature.[10] Her first novel Georgiana appeared in 1948 and had immediate critical success. This novel also began her reputation as an author who did not shy away from 'taboo' topics, namely sex and lesbianism. Georgiana is set in a girls' school, and the main character blames her problems in life on her "lesbian complex."[11] Her second novel A Diary of Love (1950) was threatened with banning in Chicago, but the municipal authorities retreated when the American Civil Liberties Union and other leading literary figures came to the book’s defense.[12]

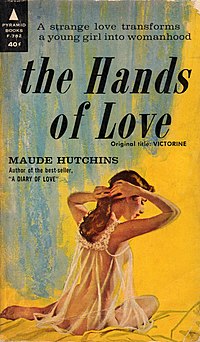

She is considered one of the foremost practitioners of nouveau roman in the English language.[13] Hutchins is best known today for her sexual coming-of-age novel Victorine,[5] which was originally published in 1959, and then republished in 2008 by New York Review Books Classics.[14] The novel focuses on a thirteen-year-old girl, Victorine, as she discovers her sexuality and place in the world. It was reviewed to be "a sly, shocking, one-of-a-kind novel that explores sex and society with wayward and unabashedly weird inspiration, a drive-by snapshot of the great abject American family in its suburban haunts by a literary maverick".[15] She wrote several other novels, short stories, and collections of poetry as well.

Marriage, controversies, and death[edit]

During her marriage with Robert Hutchins, the couple had three children:[16] Frances Ratcliffe (Franja), Joanna Blessing, and Clarissa Phelps.[7] Terry Castle writes on her relationship to motherhood: "[Maude] doted on her Great Dane, Hamlet, but “never” took her own young children out for a walk. (She and Hutchins had three daughters and it’s true: they were mostly shunted off to nannies.)"[5]

Maude and Robert lived together in New Haven, Connecticut in 1927[17] and then to Chicago in 1930.[18] The couple was said to be as glamorous and beautiful as F. Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, but in reality, their 27-year marriage was a union made in hell. Many take the side of her husband, placing the responsibility on Maude, because of how influential Robert was in academia. Milton Mayer wrote in 1993 that Mr. Hutchins was forced to spend nearly thirty years in an ‘isolated hell’, struggling to ‘keep Maude quiet’.[19] Terry Castle describes Maude in the marriage as thus: "[Maude] had no interest in the “parochial stuffiness” of academia, one says, and refused to entertain university dignitaries. Whenever “poor Bob” had to attend a presidential function, another says, Maude would throw a “window-rattling tantrum” and threaten to “blow the roof off.” She was “extravagant”, “selfish” and “constitutionally uninterested in most of mankind.”[5] It was also rumored that both of them were homosexuals to some extent, Castle writing that "[Robert Hutchins'] emotional focus was entirely on other men".[19]

Maude was known as a quite strange, unpredictable woman. She invited undergraduates, male and female, to model for her in the nude. One of her most embarrassing freaks—or so the story goes—was to send Christmas cards to all the Chicago faculty and trustees featuring a drawing of the Hutchins’ 14-year-old daughter Franja, nude and in an alarmingly suggestive pose. Later in life she learned to pilot her own plane and made several solo flights around the country.[19]

One night in 1947, Robert abruptly moved into a Chicago hotel. Maude never saw him again, and they were officially divorced in 1948.[2] Within the year, Robert married his secretary, a docile young lady called Vesta, twenty years his junior, who seemed happy to play the role of conventional academic consort. Maude, meanwhile, retreated with her two younger daughters to Southport, Connecticut, where she spent the rest of her life in relative obscurity.

Hutchins died in Fairfield, Connecticut, on March 28, 1991. A collection of her papers, photographs, and works were donated to The University of Chicago Library.

Shows and exhibits[edit]

According to a Chicago Sunday Tribune article of June 21, 1942, Maude Phelps Hutchins had shows and exhibits in the following museums and galleries:[2]

- The Brooklyn Museum

- The Grand Central Art Galleries

- Saint Louis Art Museum

- The San Francisco Museum of Art

- The Toledo Museum of Art

- Wildenstein Fine Arts Gallery, New York City

- American Fine Arts Gallery, New York City

- The New Haven Paint and Clay Club

- Albert Roullier Art Gallery, Chicago, Illinois [20]

Bibliography[edit]

- Diagrammatics (1932) co-published with Mortimer J. Adler

- Georgiana (1948)

- A Diary of Love (1950)

- Love is a Pie (1952) (collection of short stories and plays)

- My Hero (1953)

- The Memoirs of Maisie (1955)

- Victorine (1959)

- The Elevator (1962) (Short story collection)

- Honey on the Moon (1964)

- Blood on the Doves (1965)

- The Unbelievers Downstairs (1967)

Further reading[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Maude P Hutchins" in the Connecticut Death Index, 1949-2012

- ^ a b c d e Wendt, Lloyd (June 21, 1942). "The Midway's Versatile First Lady". The Chicago Tribune.

- ^ "Maud P Mcveigh" in the 1900 United States Federal Census (Year: 1900; Census Place: Islip, Suffolk, New York; Page: 27; Enumeration District: 0765; FHL microfilm: 1241165)

- ^ "Maude P Mcveigh" in the 1920 United States Federal Census (Year: 1920; Census Place: Islip, Suffolk, New York; Roll: T625_1269; Page: 13A; Enumeration District: 118)

- ^ a b c d Walker, Andrea (12 August 2008). "In Praise of Wanton Women". The New Yorker. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Maude P Mc Veigh" in the New York State, Marriage Index, 1881-1967 (New York State Department of Health; Albany, NY, USA; New York State Marriage Index)

- ^ a b "Guide to the Maude Phelps McVeigh Hutchins Collection 1930-1946". www.lib.uchicago.edu. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ "Phelps McVeigh Hutchins" in the U.S., School Yearbooks, 1900-1999 ("U.S., School Yearbooks, 1880-2012"; School Name: Yale University; Year: 1924)

- ^ a b "Maude P.H. Hutchins: Drawings and Sculpture". Renaissance Society. 19 February 1937. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Fuchs, Miriam (25 December 2020). "Hutchins, Maude (Phelps) McVeigh | Encyclopedia.com". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Bradley, Marion Zimmer (17 March 2012). "Checklist: A complete, cumulative Checklist of lesbian, variant and homosexual fiction". Project Gutenberg. Retrieved 27 December 2020.

- ^ "Maude Hutchins". www.ndbooks.com. 2011-09-08. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Nin, Anais, The Novel of the Future, p. 166, Macmillan, New York, New York, 1968

- ^ Castle, Terry. "Victorine". New York Review Books. New York Review Books. Retrieved 16 April 2015.

- ^ Kirsty (11 April 2017). "Really Underrated Books (Part Two)". theliterarysisters. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Dzuback, Mary Ann, Robert M. Hutchins: Portrait of an Educator, University of Chicago Press, Chicago, Illinois, 1991

- ^ "Maude P Hutchins" in the U.S., City Directories, 1822-1995

- ^ "Mauda P Hutchins" in the 1930 United States Federal Census (Year: 1930; Census Place: Chicago, Cook, Illinois; Page: 4A; Enumeration District: 0202; FHL microfilm: 2340157)

- ^ a b c Castle, Terry (3 July 2008). "Tickle and Flutter". London Review of Books. Vol. 30, no. 13. ISSN 0260-9592. Retrieved 2020-12-27.

- ^ Sturdy, M.F. (2015-05-05). "An Exhibition of Sculpture, Paintings and Drawings by Maude Phelps Hutchins" (Press release). Chicago, Illinois: Albert Roullier Art Galleries.

- 1899 births

- 1991 deaths

- 20th-century American novelists

- American women novelists

- 20th-century American women writers

- Novelists from New York City

- Yale University alumni

- American women sculptors

- 20th-century American painters

- 20th-century American sculptors

- Painters from New York City

- 20th-century American women painters

- Sculptors from New York (state)

- Pulp fiction writers

- Lesbian fiction

- 20th-century women sculptors