Leopard skin (clothing in Ancient Egypt)

| Leopard skin in hieroglyphs | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Netjeret Nṯrt fur apron of the Cheetah [1] | ||||||

Ba-Abi / Ba-Aba B3-3bj / B3-3b3 Soul of the (female) leopard | ||||||

| ||||||

The leopard skin was a ritual garment in Ancient Egypt. It has been documented with certainty since the Early Dynastic period (around 3000 BC). The mythological roots go back to the pre-dynastic period. In these times, the goddess Mafdet still served as the sky goddess,[2] and her cosmic functions were taken over by the sky goddess Nut in the course of ancient Egyptian history. The Ancient Egyptians therefore used the term "leopard skin" in connection with the divine panther.

During his lifetime, the leopard skin identified the king or his designated successor as a divinely legitimized ruler. In the mortuary cult, the leopard skin is mentioned in the pyramid texts as a special symbol of protection and rule for the deceased king in connection with his ascension to heaven after the opening of the mouth ceremony. After successfully ascending to heaven, the sun god Ra accepts him into the divine society. The leopard skin is the king's symbol of power, with which he undertakes his daily journey through the celestial waters alongside the sun god. The leopard skin is therefore one of the symbols that make his immortality visible.

Origins[edit]

Use of the term and origin of the name[edit]

In Egyptology, the technical terms panther or leopard skin are commonly used, although the term panther skin is mainly used in German-speaking Egyptology. Some additional references to a possible connection to the similar genet fur[3] are not documented by the written sources with regard to leopard fur. The Egyptians counted the leopard among the family of big cats and the divine desert animals. In this connection, several hieroglyphic representations were possible, for example in the short form as "The Divine" or as an ideogram. In the Old Kingdom (2707-2216 BC), the name of a deity of the dead "Kenmet" is also translated as "leopard",[4] although an equation with the leopard was also only indirectly derived there and is not certain.[5]

In the Solar Sanctuary of Nyuserre (2455-2420 BC), a larger report is dedicated to the leopard in an appendix in connection with other birthing animals. All species mentioned there are attributed "divinity"; they therefore "need no shepherd", but are the "determiners of fate".[6] An exact attribution to the cheetah or leopard is not possible, as it is only since the Middle Kingdom (2137-1781 BC) that the hieroglyph

| |

was no longer used for the word peh (lion or panther). The attribution to the leopard and cheetah could be taken from the Pyramid Texts through parallel mentions, whereby the royal panther skin and the panther skin apron are primarily mentioned. However, the unclear use of the term "leopard skin/leopard skirt" is also noticeable here, which does not allow an exact identification of leopard skin or cheetah skin.[6] A reliable attribution is only possible through textual additions, for example the cheetah as abi-mehu (narrow panther) and the leopard as abi-schemau (broad panther).

In the Middle Kingdom, the original name changed to the new form "Ba-Abi", which specifically referred to female leopards.[6] In direct connection with this is the first attested mention of the associated deity Abi in the Middle Kingdom.[7]

Mythological connections[edit]

The leopard skin was originally a garment worn by people who were very close to the king during the 1st and 2nd dynasties (3032-2707 BC); it was usually worn by the king's son. There is evidence of leopard skins being worn with the name "Shem" from the 3rd Dynasty (2707-2639 BC), although the associated priesthood had not yet been developed by this time. There may already be a reference here to the god Sameref as the "loving son of the king", who first appeared in mythology around the same time.

There is no evidence that non-royal people performed the function of "Shem" as leopard skin bearers at this time, so it is likely that the king's son performed the duties of "Shem". In the 5th Dynasty (2504-2347 BC), representations on royal temple reliefs of the Old Kingdom show in particular a linking of ancient Egyptian official titles to the leopard skin bearer; for example, the new priestly office of "Shem" is mentioned on the sed festival representations of Sahure in connection with the king's son as a leopard skin bearer.

Different representations[edit]

In Predynastic times (late 4th millennium B.C.), several types of leopard skin are depicted.[8] Bruce Williams considers it possible that the people depicted on vases from the Naqada IIC period (3800-3300 B.C.) symbolize the wearer of a leopard skin. He therefore identifies the ceremonial activity with a functionary and with that of the tjet depicted in a tomb at Hierakonpolis. However, it remains unclear in this context whether it is the skin of a leopard, cattle or a cattle-like species.[9]

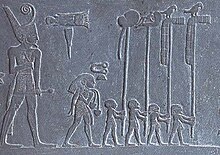

The undoubtedly oldest depiction is documented on the head of Scorpion II around 3100 BC. The leopard-skin bearer is among the king's direct escort. He is probably carrying a sheaf of ears of corn and follows a person scattering seeds from a basket into the earth.[10] Further evidence is found on the Narmer palette and the Narmer macehead.

On many relief depictions, no spots can be recognized for the leopard skin, although it was certainly present in many painted representations. On the few preserved color versions in Ramesside tombs of the kings (1292-1070 BC), the background color of the leopard skin is always yellow. The symbols are applied to the background color in black or white. In the Theban royal tombs, the leopard skin is sometimes also depicted with stars, which refers to the celestial symbolism of the leopard skin.

The most frequently used iconographic motifs show a fur robe that covers the entire upper body and a fur cloak that only partially covers it.[11] The fur cloak can be attached to the body in various ways; one possibility is to pull the fur under one arm, while the two front paws are only attached to one shoulder. The other shoulder remains free. The torso, on the other hand, is completely covered by the fur.

Other variants show a front paw and the panther's head on the shoulders or the crossing of the front paws on the chest, with both paws under the arms. The panther's head is usually placed over the shoulder past the neck, leaving the belly uncovered. The associated hairstyle is a side plait rolled forward, often in combination with a cap-like short hairstyle. Especially in the 18th dynasty (1550-1292 BC), this style was used, for example, by Amenophis I to Thutmosis III, following early traditions.

Historical significance of the leopard skin[edit]

The leopard-skin bearer also wore the sidelock of youth, which identified him as the king's son. In iconography, the sidelock of youth also served in the further course of ancient Egyptian history to identify primarily those royal descendants who were eligible as designated heirs to the throne. As part of his priestly function as Tjet or "Shem" and as the embodiment of Sameref, the eldest son of the king, who was adorned with the leopard skin, thus acted as a mediator between the king and the world of the gods.[12]

Early period (3100-2707 BC)[edit]

A relief fragment from the area of the former temple of Hathor in Gebelein depicts the leopard skin bearer in the royal cult. The limestone block, which is located in the Museo Egizio in Turin, is usually dated to the 2nd or early 3rd dynasty.[13] Egyptologists interpret the actions of the leopard skin bearer as a foundation or hunting ritual and as a ceremony within the Sed festival. There is no doubt, however, that it was a symbolic act, as the crown goddess Unut was also involved in the event. The leopard skin bearer was active in the context of the Horus procession, in which the royal exercise of power as the maintenance of kingship was the dominant motif of the ceremonial acts.[12]

Old Kingdom (2707-2216 BC)[edit]

In royal rituals of the Old Kingdom from the 5th Dynasty onwards, the leopard skin was exclusively the costume of the Shem priest, who was the person among the king's priests who walked directly in front of the king's palanquin in processions. Wolfgang Helck makes it clear that only the eldest son of the king had the royal permission to be close to him.[14] This connection is also shown in the festive scenes of the Pepi II pyramid, which is why it can be assumed that the office of the leopard skin bearer as Shem priest in the associated ceremonies was either occupied by the king's son or symbolically identified him as the acting person.[12]

Middle Kingdom (2137-1781 BC)[edit]

In the Middle Kingdom, a torso made of granite for Amenemhet III documents the possibility that a designated king could also appear as a leopard skin bearer. Before his sole accession to the throne, Amenemhet III reigned together with his father Sesostris III for around twenty years. Amenemhet III can be seen on the granite block wearing a wispy wig and a strand of pearls in several rows, known as a "menat". The leopard skin, which is mainly worn backwards, ends on his shoulders.

Wolfhart Westendorf emphasizes that the iconography of the Middle Kingdom corresponds to the traditional priestly dress of Tjet and shows Amenemhet III in the mythical phase of the divine Horus before he took the place of his father.[15] In addition, Amenemhet III reveals the principle of the young Horus in Chemmis embodied by the deity Iunmutef. The background was formed by the mythological idea that the young Horus stayed in the secret place of Chemmis in order to grow to manhood hidden from Set by Isis, with the leopard skin identifying Amenemhet III as a young Horus and a ritual expert.[12]

New Kingdom (1550-1070 BC)[edit]

The New Kingdom was characterized by great upheaval. Texts on the dead and coffins were combined to form the Book of the Dead. Life after death and the journey to Sechet-iaru in the Duat was now possible for all those who were financially able to have a personal Book of the Dead written. Accordingly, the leopard skin was part part of the dress of several high priests without being tied to a specific deity; in addition, simple priests of lower rank were also allowed to wear the leopard skin.[12]

However, the costume of the leopard skin was still mainly associated with the office of Shem priest. Seti I elevated the figure of Horus Iunmutef, who until then had only been revered as a mystical figure, to the status of the new deity of the dead and had himself appointed as his leopard skin-bearing high priest. Seti I is also depicted in the Temple of Amun in Karnak as the high priest of Amun, who accompanies the royal barque in his role as the son of the god during a procession:

"Amun sees his son carrying him, the king lifting up the one who created him. My hands carry my glorious father (Amun). My body is pure through the leopard skin that is on me." - Seti I[12]

As in the case of Amenemhet, Ramesses II, the son of Seti I and co-ruling king, also wore the leopard skin at a young age. In the mortuary temple of Seti I in Abydos, the Sameref priests of Ramesses II wore the leopard skin in the sacrificial cult for his father Seti I in front of the royal ancestors. Ramesses II is positioned behind Seti I in the associated depictions and, as the rightful heir, refers to the dynasty of kings who reigned before him, subtitled by name.[12]

Late period (664-332 BC)[edit]

In the late period, an extended circle of leopard skin bearers was added to the mythological interpretation. In particular, it was now the dress of the queens of the kingdom of Kush. The Kushite king's mothers saw themselves in the role of the goddess Isis, who, as the mother of Horus, was responsible for the royal successors.[16]

The queens had a decisive influence in the coronation ritual. Therefore, they assumed the ritual execution of the necessary ceremonial acts in a reinterpretation of Sameref's earlier function as the bearer of the leopard skin. In doing so, they appropriated the content of the Osiris myth and adopted the attributes of the deity Horus-Iunmutef.[16]

The leopard skin in the cult of the dead[edit]

As early as the Old Kingdom, the tomb owner is often depicted wearing a leopard skin cloak on false doors and the entrance areas of burial chambers. This is supplemented by ritual acts in connection with the display of livestock and the provision of offerings. In the cult of the dead, the leopard skin does not represent an earthly office, but shows the ideal rank of the grave owner, which is achieved with the completion of the burial and, as the wearer of the leopard skin, enables him to live on in the sacred land of the deceased with magical powers.[17] In the Middle Kingdom, further functions of the leopard skin are added with the practice of the cult of the dead. It was also part of the standard equipment of those involved in the area of mortuary sacrifices; usually the eldest son or the Shem priests, who were elevated to the rank of sorcerer and thus received the status of "divinely endowed and recognized spirits of the dead".[18] Tomb reliefs and stelae show the newly added ritual costume alongside the tomb owner in the traditional role. With the beginning of the New Kingdom, the depictions of the leopard skin predominate on account of its connection to the priestly cult of the dead as the "loving son" and "first of the sacrificial cortege". In the opening of the mouth ceremony, however, the leopard skin retained its central effect as a cult object of the deceased.[19]

Unas (2380-2350 BC)[edit]

Unas was the first king (pharaoh) to have the underground pyramid chambers inscribed with reciting funerary texts in the form of "death sayings".[20] With the use of the pyramid texts, Unas established a tradition that ran through the pyramid buildings of the kings and queens of the 6th Dynasty and formed the basis for later funerary liturgies such as coffin texts and the Ancient Egyptian Book of the Dead.[21] The leopard skin appears in the texts of Unas in direct reference to the cosmic rebirth of the king. The later Book of Nut describes the daily journey of the sun god Ra. The texts of the dead that serve as a basis for this describe the deceased king who, like Ra, travels between the horizons to purify himself at night after sunset in Sechet-iaru in the Merencha, in order to start the day together with Ra again the next morning.

"It (the leopard skin) is perfect for Unas and his Ka. The doors of the starry heavens are opened for this king, that he may pass through them. His leopard skin is on him, his Ames scepter[A 1] is in his arm, his Aba scepter[A 2] is in his hand. This king is unharmed with his flesh, perfect it is for this king with his name, this king lives with his Ka. A sacrifice the king gives that the son may be on thy throne. Let thy garment be the leopard skin, let thy garment be the Chesed skirt, may thou walk in thy sandals." - Pyramid Texts 224, 225, 338 a-b[22]

The contents of the texts of the dead show that, in addition to the heavenly rule of the deceased king, the leopard skin is also associated with his integrity. This condition was absolutely necessary for heavenly existence, as the absence of the leopard skin had negative effects on the deceased's afterlife. With the sacrificial formula, the king is granted regency over the realms of Horus and Seth, which are located in the eastern heavens.

Tutankhamun (1332-1323 BC)[edit]

Tutankhamun's tomb is particularly noteworthy because of the leopard skin found in it. A wall painting depicts the opening of the mouth ceremony, in which Tutankhamun's successor Ay himself acts as leopard skin bearer and Shem priest. In addition to the numerous grave goods, two leopard skins were found in the tomb: one made of real leopard skin, decorated with golden stars, with the head made of wood and covered in gold, while the other is a replica made of linen.[23]

The same motif can be seen on a group statue in the Louvre, where Tutankhamun is dressed in a star-covered leopard skin cloak and stands between the legs of a statue of Amun,[24] who embraces him from behind. Both arms of the god are resting on Tutankhamun's upper arms. In this depiction, the symbolic father-son relationship is clearly recognizable, in which Tutankhamun appears as the "loving son" of his "father" Amun. The leopard skin is the visual sign of the family ties between Tutankhamun and Amun. In his role as divine son, Tutankhamun is thus the rightful bearer of the leopard skin.

References[edit]

- ^ Rainer Hannig: Grosses Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch: (2800–950 v. Chr.). p. 470.

- ^ Altmüller, Hartwig (1965). Die Apotropaia und die Götter Mittelägyptens: Eine typologisch und religionsgeschichtliche Untersuchung der sogenannten "Zaubermesser" des Mittleren Reichs. Teil 2: Katalog. Dissertation. Universität München. pp. 58–59.

- ^ Picture of an Ethiopian genet (Genetta abyssinica)

- ^ Leitz, Christian (2002). Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. Leuven: Peeters. p. 289. ISBN 9042911468.

- ^ Hannig, Rainer. Großes Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch: (2800–950 v. Chr.). p. 955.

- ^ a b c Edel, Elmar (1961). Zu den Inschriften auf den Jahreszeitenreliefs der „Weltkammer“ aus dem Sonnenheiligtum des Niuserre. Nachrichten der Akademie der Wissenschaften in Göttingen. Vol. 8. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. p. 244.

- ^ Leitz, Christian (2002). Lexikon der ägyptischen Götter und Götterbezeichnungen. Vol. 1. Leuven: Peeters. p. 10. ISBN 2877236447.

- ^ Hendrickx, Stan (1998). "Peaux d'animaux comme symboles prédynastiques. À propos de quelques représentations sur les vases White Cross-lined". Caribéens d’Egyptologie (CdE) (73): 203–230.

- ^ Williams, Bruce (1997). "The wearer of the leopard-skin in the Naqada Period". In Phillips, Jacke (ed.). Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Near East. Studies in honour of Martha Rhoads Bell. Vol. 2. San Antonio: Van Siclen. pp. 483–496. ISBN 0933175442.

- ^ Asselberghs, Henri (1961). Chaos en beheersing. Documenten uit aeneolithisch Egypte. Leiden: Brill. Plate XCVIII, figure 173.

- ^ Staehelin, Elisabeth (1966). Untersuchungen zur ägyptischen Tracht im Alten Reich. Berlin: Hessling. p. 36.

- ^ a b c d e f g Rummel, Ute (2003). Pfeiler seiner Mutter – Beistand seines Vaters: Untersuchungen zum Gott Iunmutef vom Alten Reich bis zum Ende des Neuen Reiches. Hamburg. pp. 31–37.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Gundlach, Rolf; Rochholz, Matthias (1998). Feste im Tempel. 4. Ägyptologische Tempeltagung, Köln, 10.–12. Oktober 1996. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. p. 223. ISBN 344704067X.

- ^ Helck, Wolfgang (1954). Untersuchungen zu den Beamtentiteln des ägyptischen Alten Reiches. Ägyptologische Forschungen (ÄgFo). Glückstadt. pp. 16–17.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Westendorf, Wolfhart (1988). Das alte Ägypten. Munich: Naturalis. p. 94. ISBN 388703712X.

- ^ a b Lohwasser, Angelika (2001). Die königlichen Frauen im antiken Reich von Kusch: 25. Dynastie bis zur Zeit der Nastasen. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 324–326. ISBN 3447044071.

- ^ Altenmüller, Hartwig (1998). Die Wanddarstellungen im Grab des Mehu in Saqqara. Mainz: Zabern. p. 40. ISBN 3805305044.

- ^ Helck, Wolfgang (1984). "Schamane und Zauberer". In Gutbub, Adolphe (ed.). Mélanges Adolphe Gutbub. Montpellier: Université de Montpellier. p. 107. ISBN 2905397039.

- ^ Schulz, Regine (1992). Die Entwicklung und Bedeutung des kuboiden Statuentypus: Eine Untersuchung zu den sogenannten Würfelhockern. Hildesheim: Gerstenberg. p. 475.

- ^ Assmann, Jan (2003). Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten. p. 323.

- ^ Goelet, Ogden (1998). A Commentary on the Corpus of Literature and Tradition which constitutes the Book of Going Forth By Day. San Francisco: Chronicle Books. pp. 139–170.

- ^ Staehelin, Elisabeth (1966). Untersuchungen zur ägyptischen Tracht im Alten Reich. Berlin: Hessling. p. 31.

- ^ Edwards, I. E. S. (1977). The treasures of Tutankhamun. Harmondsworth: Penguin Books. pp. 104–105. ISBN 0140042873.

- ^ Louvre E 11609

Bibliography[edit]

- Assmann, Jan (2003). Tod und Jenseits im Alten Ägypten Beck, München , ISBN 3-406-49707-1. Munich: Beck. ISBN 3406497071.

- Brentjes, B. (1965). "Das Leopardenfell im Alten Orient". Das Pelzgewerbe (6). Berlin: Hermelin-Verlag Dr. Paul Schöps: 243–253.

- Hannig, Rainer (2006). Grosses Handwörterbuch Ägyptisch-Deutsch: (2800–950 v. Chr.). Mainz: von Zabern. ISBN 3805317719.

- Rummel, Ute (2009). Verbovsek, Alexandra; Burkard, Günter; Junge, Friedrich (eds.). "Das Pantherfell als Kleidungsstück im Kult: Bedeutung, Symbolgehalt und theologische Verortung einer magischen Insignie". Imago Aegypti. (International Journal for Egyptological and Coptological Art Research, Visual Theory and Cultural Studies, in cooperation with the German Archaeological Institute, Cairo Department). 2. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht: 109–152. ISBN 3525470118.

- Staehelin, Elisabeth (1966). Untersuchungen zur ägyptischen Tracht im Alten Reich. Berlin: Hessling.

- Vandier, Jacques (1962). Le Papyrus Jumilhac. Paris: Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique. pp. 113–114.

- Williams, Bruce (1997). "The wearer of the leopard-skin in the Naqada Period". In Phillips, Jacke (ed.). Ancient Egypt, the Aegean, and the Near East: Studies in honour of Martha Rhoads Bell. Vol. 2. San Antonio (TEX): Van Siclen. pp. 483–496. ISBN 0933175442.