Latin American Gothic

Latin American Gothic is a subgenre of Gothic fiction that draws on Gothic themes and aesthetics and adapts them to the political and geographical specificities of Latin America. While its origins can be traced back to 20th century Latin American literature and cinema, it was in the first decades of the 21st century that it gained particular relevance as a literary current.

Characteristics

[edit]If Gothic fiction, in general, is characterized by an appeal to negative emotional responses triggered by confrontation with alterity, the narrative transculturation exercised in its Latin American variety doubles the stakes by rendering both foreign and local elements alien.[1] Themes such as the threat of the supernatural, the intrusion of the past into the present, the blurred line between science and religion, or the repression of sexuality serve to unveil the spectres that haunt Latin America's historical past and current political situation in order to explore the sources of fear and unease in its different countries and regions. In this way, the resources of Gothic fiction make it possible to address issues such as the genocide of Indigenous peoples, class struggle, enforced disappearances, and patriarchal violence.

Origins

[edit]Despite being sometimes portrayed as a ruptural phenomenon, the emergence of Gothic themes and topics in 21st century Latin American literature can also be regarded as a variation on a regional literary tradition woven into magic realism and the fantastic.[2] Literary scholar Soledad Quereilhac argues that the circulation of European Gothic works in nineteenth-century Argentina, along with the proliferation of pseudoscientific and occult themes in the popular press, led to a local renewal of the genre, as witnessed by the work of authors such as Leopoldo Lugones, Eduardo Wilde, Eduardo Holmberg and, most notably, Horacio Quiroga.[2] The novel La amortajada (1938), by Chilean writer María Luisa Bombal, has been often singled out as one of the most direct antecedents of contemporary Latin American Gothic fiction.[3][4] Bombal's novel, narrated first-person by a dead woman in her coffin and touching on themes such as abortion and issues of power and submission, was a major influence on Juan Rulfo's Pedro Páramo (1955), which, in addition to being a precursor of magic realism, can also be credited with having helped to pave the way for the regional development of the Gothic.[5] In the second half of the 20th century, some remarkable forerunners of this literary subgenre include the macabre and darkly erotic short stories by Uruguayan writer Armonía Somers (pub. 1950–1994) and the haunted house themed novella La mansión de Araucaima (1973), which Colombian author Álvaro Mutis wrote following a debate with Spanish-Mexican filmmaker Luis Buñuel over the possibility of transposing the themes of English Gothic fiction to a tropical setting.[1]

Leading figures

[edit]

The Latin American literary Gothic stands out for its predominantly female protagonism. The most widely known author working in this vein is arguably Mariana Enríquez, an Argentine writer whose works feature disturbed women, sinister children, and eerie physical environments and deal with themes such as the legacy of military dictatorships, the emotional consequences of exile, femicide, and police violence. She achieved international recognition after the publication of her second book of short stories, Things We Lost in the Fire (2016), which became a bestseller and was translated into more than a dozen languages. She later won the Herralde Novel Prize for Our Share of Night (2019) and was shortlisted for the 2021 International Booker Prize for Megan McDowell's English translation of her first book of short stories, The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (2009).[6][7]

Ecuadorian writer Mónica Ojeda rose to prominence thanks to the critical acclaim she received for her third novel Jawbone (2018), which follows the story of a horror-obsessed teenage girl who is kidnapped by her literature teacher and was shortlisted, in translation by Sarah Booker, for the 2022 National Book Award. Ojeda's 2020 short story collection Las voladoras—which includes Caninos, previously published in 2017—explores themes such as gender violence, abortion, incest, child abuse, sexuality, and religion through the lens of what she defines as "Andean Gothic". It earned Ojeda further critical acclaim and was shortlisted for the Ribera del Duero literary award.[8][9]

Giovanna Rivero is one of the most successful contemporary writers in her native Bolivia. Her work has begun to gain international recognition since the publication of her book of short stories Fresh Dirt from the Grave (2021), which moves between horror and science fiction and expands the boundaries of the Gothic to engage with pre-Columbian ritual and folk tales.[10]

Michelle Roche Rodríguez's novel Malasangre, about a young girl from a Catholic and conservative family who becomes a blood-sucking monster in 1920s Caracas, was shortlisted for the 2021 Celsius literary award, which recognises the best works of science fiction, fantasy, and horror written in Spanish.[11] Roche Rodríguez has been compared to her countryman Juan Carlos Chirinos, who also makes use of Gothic aesthetics to portray the social reality of Venezuela.[12]

Other authors sometimes classed within the Latin American Gothic movement are María Fernanda Ampuero, Fernanda Melchor, and Samanta Schweblin.

Film and television

[edit]

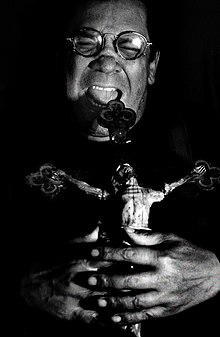

In the 1980s, Colombian filmmakers Carlos Mayolo and Luis Ospina, members of the so-called "Cali group" or "Caliwood", coined the expression "Tropical Gothic" to refer to the aesthetics of their films, which feature monstrous narratives set against a backdrop of sunlight, warm climates, and an abundance of natural resources.[13] According to scholars Justin D. Edwards and Sandra Guardini Vasconcelos, the Tropics are fertile ground for the Gothic due to its history of violence and transculturation that involves both the myths that were brought to the region by the European settlers and haunt it under the guise of its colonial past, and an older belief system that is constantly in the process of being unearthed, acknowledged, and remembered in awe and wonder.[13] Mayolo directed the films Bloody Flesh (1983), a tale of incest and cannibalistic undead creatures set during the military dictatorship of Gustavo Rojas Pinilla, and La mansión de Araucaima (1986), based on the novella by Álvaro Mutis about a mysterious house that keeps a group of people trapped by their own fears and repressed desires. Luis Ospina was the director of Pura Sangre (1982), which is one of the first Colombian vampire films and which, like Bloody Flesh, uses vampirism as an allegory of the bleeding of the working classes of the Cauca Valley by the local businessmen.

Among more recent films, La Llorona (2019), by Guatemalan filmmaker Jayro Bustamante, places the Mesoamerican ghost legend of La Llorona in the context of the 1981-1983 Mayan genocide. The film was nominated for the Golden Globe, Goya, and Ariel awards and won the Director's Award at the Giornate degli Autori of the Venice Film Festival.

Also critically acclaimed was Pablo Larraín's black comedy El Conde (2023), in which Chilean dictator Augusto Pinochet is portrayed as a two hundred and fifty year old vampire. It received an Academy Award nomination for Best Cinematography and was nominated to the Golden Lion and winner for Best Screenplay at the Venice Film Festival.

On television, the miniseries Santa Evita (2022), inspired by the novel of the same name by Tomás Eloy Martínez (1995), offers a fictionalised account of the fate of the embalmed corpse of Eva Perón framed in a phantasmagorical atmosphere and bordering on the supernatural.

Other media

[edit]The style of Argentine visual artist Santiago Caruso, who illustrated the covers of many works of Gothic, horror, and fantasy fiction, ranging from Alejandra Pizarnik's The Bloody Countess to the Comte de Lautréamont's Les Chants de Maldoror, has often been described as Gothic.[14]

English translations

[edit]María Fernanda Ampuero: Cockfight (tr. Frances Riddle for Feminist Press, 2020), Human Sacrifices (tr. Frances Riddle for Feminist Press, 2023).

Mariana Enríquez: Our Share of Night (tr. Megan McDowell for Granta Books, 2023), The Dangers of Smoking in Bed (tr. Megan McDowell for Granta Books, 2021), Things We Lost in the Fire (tr. Megan McDowell for Portobello Books, 2018).

Fernanda Melchor: Hurricane Season (tr. Sophie Hughes for Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2020), This is Not Miami (tr. Sophie Hughes for Fitzcarraldo Editions, 2023).

Mónica Ojeda: Jawbone (tr. Sarah Booker for Coffee House Press, 2022), Nefando (tr. Sarah Booker for Coffee House Press, 2023).

Giovanna Rivero: Fresh Dirt from the Grave (tr. Isabel Adey for Charco Press, 2023).

Samanta Schweblin: Fever Dream (tr. Megan McDowell for Riverhead Books, 2017), Little Eyes (tr. Megan McDowell for Riverhead Books, 2020), Mouthful of Birds (tr. Megan McDowell for Riverhead Books, 2019), Seven Empty Houses (tr. Megan McDowell for Riverhead Books, 2023).

References

[edit]- ^ a b Eljaiek Rodríguez, Gabriel Andrés (2017). Selva de fantasmas: el gótico en la literatura y el cine latinoamericanos. Ópera eximia (Primera edición ed.). Bogotá: Pontificia Universidad Javeriana. ISBN 978-958-781-086-8.

- ^ a b Casanova-Vizcaíno, Sandra; Ordiz, Inés, eds. (2017). Latin American gothic in literature and culture. Routledge interdisciplinary perspectives on literature. New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-1-138-23422-2.

- ^ "Raíces y desinencias del nuevo gótico latinoamericano". www.elsaltodiario.com. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ "Gótico latinoamericano". www.lavanguardia.com. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Miramontes, Ana (2004). "Rulfo lector de Bombal" (PDF). Revista iberoamericana. LXX (207): 491–520.

- ^ Fernández, Silvia Beatriz (2022-11-29). "El terror gótico latinoamericano de Mariana Enriquez como propuesta virtual en el museo Malba: una crítica social y de género". Amérique Latine Histoire et Mémoire (44). doi:10.4000/alhim.11238. ISSN 1628-6731.

- ^ ""No quiero que me saquen las pesadillas" | Babelia | EL PAÍS". 2017-10-07. Archived from the original on 2017-10-07. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Marcos, Javier Rodríguez (2018-05-30). "¿Quién demonios es Mónica Ojeda?". El País (in Spanish). ISSN 1134-6582. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ "El Telégrafo - Noticias del Ecuador y del mundo - Ojeda, Baudoin y Erlés entre finalistas del Premio Ribera del Duero". 2020-02-19. Archived from the original on 2020-02-19. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ "Fresh Dirt from the Grave". Charco Press. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ Literatura, Cine y (2020-07-08). ""Malasangre": La novela revelación de la nueva literatura venezolana". Cine y Literatura (in Spanish). Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ "Una historia de vampiros en Venezuela". Diario ABC (in Spanish). 2020-03-20. Retrieved 2024-03-13.

- ^ a b Ajuria Ibarra, Enrique (2022-03-24), "Latin American Gothic", Twenty-First-Century Gothic, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 263–275, doi:10.1515/9781474440943-020, ISBN 978-1-4744-4094-3, retrieved 2024-03-14

- ^ Davis, David (2014-10-06). "Interview: Santiago Caruso | David Davis". Weird Fiction Review. Retrieved 2024-03-14.