Jeremiah Daniel Baltimore

Jeremiah Daniel Baltimore | |

|---|---|

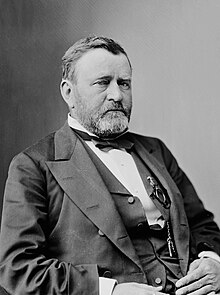

Image of Baltimore from 1887. | |

| Born | April 15, 1852 Washington, DC, U.S. |

| Died | July 29, 1929 (aged 77) Washington, DC, U.S. |

| Alma mater | Livingstone College |

| Occupation | Engineer |

| Political party | Republican |

Jeremiah Daniel Baltimore (April 15, 1852 – July 29, 1929) was an engineer and educator in Washington, D.C. For many years, he was an engineer in the service of the United States Navy and served as chief engineer at the Freedmen's Hospital. He was also a teacher of mechanics, and was responsible for mechanical instruction in the African American schools in the city from 1890 to 1922. He was on the trial board of the Naval battleship USS Texas (1892) and was among the organizers and officers of the Potomac Hospital and Training School. In 1903 he was elected a member of the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia. In 1915, he was made member of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Art, Manufactures, and Commerce of London.

Early life and education

[edit]This section needs additional citations for verification. (February 2024) |

Jeremiah Daniel Baltimore was born in Washington DC on April 15, 1852 to Thomas and Hannah Baltimore. While Thomas was a Catholic, Jeremiah followed his mother and became a Methodist, being baptized at the Wesley Zion Church in 1866. He attended Enoch Ambush's school and then Washington, D.C. public schools. As a boy he liked to experiment with steam and told his mother that he wished to be an engineer. His mother said that this was impossible as she and her father would not be able to get him through school.

His experiments continued and he made a steam boiler and attached it to an engine, but this failed. In spite of this, the pastor at his church, Reverend William P. Ryder placed it in an exhibition at the Wesley Zion Sunday School and then it was put on exhibition in the United States Treasury Department where officers and employers were impressed. This encouraged Baltimore to keep trying. He then used bricks and flower pots to hold molten metal, using a kitchen stove to melt brass, and using a file, old shears and an old knife for cutting, created a steam engine of the horizontal high pressure style with a tubular boiler. The engine was brought to the patent office with the aid of Anthony Bowen, a Washington D.C. City Councilman. The device was widely discussed in the press,[1] appearing the Iron Age of London[2] and locally in the Sunday Chronicle.

Young Jeremiah went to the White House and sent a copy of the article to the desk of President Ulysses S. Grant, who invited Baltimore to his office. Grant gave Baltimore a card to deliver to the Secretary of the Navy to ask that Baltimore be given work in the Navy Yard to learn and work on the machinery.[1]

Early engineering career

[edit]

Baltimore was then given a position as apprentice in the department of steam engineering at the Washington Navy Yard. Baltimore faced a lot of prejudice on account of his color, and, after a few months, complained. Professor John M. Langston brought the complaints to the Secretary of the Navy who allowed Baltimore to transfer to the Philadelphia Navy Yard. He again was discriminated against, but endeavored to study on his own early in the mornings and after work. His study paid off and he was admitted to the Franklin Institute in Philadelphia. He was the second black person to be admitted at the institute. His apprenticeship continued and every sign of growth and learning was countered with further examples of prejudice and intimidation. Despite this, he finished his apprenticeship about September 6, 1873, working for three years and six months.[1]

He then was assigned to the Philadelphia Naval Station on League Island to assist repairs on Monitors. He was released from the job when force sizes reduced. He then worked at a large mill, and next at a manufacturing firm, Sellers & Brother after being refused from Cramp & Sons and multiple previous applications at Sellers & Brother. He resigned for health reasons and moved back to Washington, D.C.[1]

In Washington he became engineer of the United States Coast Survey and opened a general repair shop. On August 2, 1880, he was appointed chief engineer and mechanician at the Freedmen's Hospital.[1] He attended Howard University Medical College in 1880-1881 and received an A.M. (a master's degree) in 1883 from Livingstone College.[3] He was frequently noted for inventing a pyrometer device, for which he received a patent. As an engineer, he was a member of the Mechanics Union and played a key role in merging black and white unions in 1887.[1]

Public life

[edit]Baltimore was active in Republican politics. In 1876 he was secretary of the 17th District Republicans and was a delegate to the 1876 Republican National Convention in Cincinnati.[4] In 1880, he was made chairman of the group and was again delegate at the National convention in Chicago.[5]

He was recommended as a trustee for public schools in 1883[6] and in 1889.[7]

In 1890, he was appointed to take charge of machine instruction in the colored public schools in Washington, a position he held until 1922.[2] His position included the responsibility of teaching at the Armstrong Manual Training School. He was highly respected as a professor, adopting the methods of the United States Bureau of Steam Engineering. One of his techniques was that he constructed an engine made of glass to help the students see the workings of the engine and the effect of heat on water.[8]

In 1895 he was selected by the Navy to serve as assistant engineer officer on the trial board of the battleship, USS Texas.[2] In 1906, Baltimore was among the organizers of the Potomac Hospital and Training School and was its treasurer. The organizers included Reverend W. J. Howard, Dr. A. R. Collins, and Dr. Harry J. Williams.[9]

Honors and affiliations

[edit]Baltimore was very active in DC Society. In 1875, he was elected recording secretary of the Colored Sabbath School Union of Washington, DC.[10] However, Baltimore's belief in scientific reason occasionally put him at odds with the religious community, as in 1876 when he took part in a debate with Dr. J. L. N. Bowen wherein Baltimore argued that geological evidence showed that the first verses of Genesis did not definitively fix the age of the world at about 6,000 years.[11]

He was a member of a number of literary and debating clubs, including in the late 1870s as an officer of "The Institute" led by Charles N. Otey, John Wesley Cromwell, and J. E. Blunheim,[12] and an officer of the Young Men's Brilliant Star Association led by J. G. Mihales and J. Hicks;[13] and in the 1890s as leader of the Literary Lyceum of Metropolitan Zion Wesley Church along with Dr. S. A. Sumby[14] and the National Congressional Lyceum.[15]

In 1882 he was made president of an association to promote industry among Washington blacks.[16] He was an officer of the Association of Steam Engineers led by William H. Thomas and H. H. Anseer in 1905.[17]

He was an officer of the Washington Branch of the Negro Development and Exposition Company of the Jamestown Exposition which developed presentations for the Jamestown Exposition in 1907 in Norfolk, Virginia.[18]

He was a member and one of the first vice presidents of the Oldest Inhabitants Club. Also, he was a Mason and affiliated with the Eureka Lodge, F. A. A. M and the Old Ark Lodge, G. U. O. of O. F.[19]

Beyond his activities, he was highly honored while still alive. In 1903 he was elected a member of the Franklin Institute of Philadelphia. In 1915 he was made member of the Royal Society for the Encouragement of Art, Manufactures, and Commerce of London.[2]

Personal life and death

[edit]Baltimore was for a long time a trustee of the Metropolitan A. M. E. Zion Church in Washington, DC.[20] On May 29, 1872 he married Ella V. Waters.[1] Ella died May 7, 1889. She was a member of the Daughters of Levi and the Young Ladies Brilliant Star and upon her death was a member of the Metropolitan A. M. E. Zion church.[21]

Baltimore remarried to Jeanett E. Anderson in November 1908.[22] Jeanett was director of art in the public schools. He had two sons, attorney Richard L. and Jeremiah A. He had one daughter, Ella A. Bryant.[19]

Baltimore died the evening of Monday, July 29, 1929. At his death, he was a member of the 19th Street Baptist Church, where his funeral was held.[19]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e f g Simmons, William J., and Henry McNeal Turner. Men of Mark: Eminent, Progressive and Rising. GM Rewell & Company, 1887. pp. 267-272

- ^ a b c d The Horizon, The Crisis, February 1924, p. 181

- ^ Lamb, Daniel Smith. A Historical, Biographical and Statistical Souvenir. Beresford, 1900, p. 234

- ^ "Seventeenth District. National Republican". National Republican. June 7, 1876. p. 4.

- ^ "The Chicago Convention, Evening Star". Evening Star. February 6, 1880. p. 4.

- ^ "A South Washington Delegation, Evening Star". Evening Star. June 28, 1883. p. 5.

- ^ "Want a Trustee from South Washington, Evening Star". Evening Star. August 16, 1889. p. 8.

- ^ "A Leader of his Race, The Times (Philadelphia, Pennsylvania)". The Philadelphia Times. July 28, 1892. p. 4.

- ^ "Site for New Hospital, The Washington Post". The Washington Post. April 5, 1906. p. 4.

- ^ "Sunday Schools, National Republican". National Republican. July 7, 1875. p. 4.

- ^ "Science and Religion. National Republican". National Republican. January 27, 1876. p. 4.

- ^ "The Institute, National Republican". National Republican. March 9, 1876. p. 4.

- ^ "[No Headline], National Republican". National Republican. March 15, 1876. p. 4.

- ^ "[No Headline], The Washington Bee". The Washington Bee. March 29, 1890. p. 3.

- ^ "A New Lyceum, The Washington Bee". The Washington Bee. December 11, 1897. p. 5.

- ^ "Letter from Washington". The Baltimore Sun. May 1882. p. 4.

- ^ "Address on Steam Engineering, Evening Star". Evening Star. November 15, 1905. p. 10.

- ^ "Negro Exhibit at Expo". The Washington Post. December 23, 1906. p. 1.

- ^ a b c "Clipping from The New York Age". The New York Age. August 10, 1929. p. 10.

- ^ "Quarterly Conference, Evening Star (Washington, DC)". Evening Star. July 4, 1907. p. 11.

- ^ "[No Headline], The Washington Bee". The Washington Bee. May 11, 1889. p. 3.

- ^ "[No Headline], The Washington Bee". The Washington Bee. November 21, 1908. p. 5.

- 1852 births

- 1929 deaths

- African-American activists

- 19th-century American educators

- 19th-century American engineers

- 20th-century African-American educators

- 20th-century American educators

- 20th-century American engineers

- Activists from Washington, D.C.

- African-American engineers

- American civil rights activists

- American Freemasons

- Engineers from Washington, D.C.

- Howard University College of Medicine alumni

- Livingstone College alumni

- United States Navy engineering officers

- 19th-century African-American educators