James Reuel Smith

James Reuel Smith | |

|---|---|

James Reuel Smith, photographic self-portrait, c. 1893–1905 | |

| Born | 1852 Skaneateles, New York, U.S. |

| Died | November 12, 1935 (aged 82–83) Yonkers, New York, U.S. |

| Known for | documentary photography |

| Spouse | Elizabeth Thompson |

James Reuel Smith (1852–1935) was an American photographer and amateur historian who worked in the late 19th century to early 20th century. He was known for his documentary photographs of historical springs and wells in New York City before they were buried beneath the concrete of the rapidly growing city.[1][2][3] Many of these natural water resources disappeared as the New York municipal water system developed.[4][5]

Smith's photographs documented a vanishing way of life in urban America. Drawing and fetching water had been an essential activity of daily life prior to the development of the modern municipal water system.[6] In the 1870s New York City undertook efforts to eradicate the natural open wells and springs as they were perceived to be hazardous to health. The official municipal source for city water was the Croton Aqueduct which was endorsed by the NYC sanitation officers, rather than local neighborhood wells and springs.[7]

Early life[edit]

Smith was born in Skaneateles, New York, in 1852.[1] He was the elder of two sons.[7] His mother, Celestia A. Mills, died five years after marrying his father, Reuel Smith, who was known as "Little Smith". His father remarried, and Smith was sent to live at a cousin's home.[1]

His father was a partner in the Smith & Mills shipping firm, and made his fortune shipping rice, sugar and cotton to England.[7]

Work[edit]

Smith's family money allowed him to actively engage in photography as a hobby. The primary subjects of his photographs were the springs and wells of New York City. Between 1897 and 1901 he traveled by bicycle throughout Manhattan and the Bronx investigating and photographing over 160 wells and springs.[8][9] He was a meticulous note-taker, and kept detailed records of the conditions and locations of these historical water resources.[1] The New York Historical Society wrote on its collection of Smith's photographs, "Springs were very important to Mr. Smith. He made careful notes regarding each aquiferous site, and he always had in mind the publication of his findings."[6]

Smith also produced a small collection of photographs of wells in Brooklyn.[10]

Smith's photographs were a contribution to the visual culture of New York City as they documented a vanishing way of life in urban America. The daily act of drawing and fetching water had been an essential activity of life before the development of the modern municipal water system.[6] During the 1870s the city embarked on efforts to eradicate the historical open wells and springs as these natural sources of water were seen as a health hazard by NYC sanitation officers. The Croton Aqueduct fed by the Croton-Hudson Reservoir was at that time the official municipal source for city water.[7]

Smith later traveled to Europe to photograph springs and wells, an activity that led to his book, Springs and Wells in Greek and Roman Literature, Their Legends and Locations (1922).[1][11] The book covered various regions in Italy and Greece including Peloponnesus, Central Greece, Magna Graecia, Greek Islands and Asia Minor, as well as other countriesEurope, Africa and the Middle East.[11]

Smith's photographic work on New York's natural water resources was not made public until after his death, and his book, Springs and Wells of Manhattan and the Bronx, New York City at the End of the 19th Century was published posthumously in 1938.[6] However Smith wrote the introduction to his book before his death,[12] including "In the days, not so very long ago, when nearly all the railroad mileage of the metropolis was to be found on the lower half of the Island, nothing was more cheering to the thirsty city tourist afoot or awheel than to discover a natural spring of clear cold water, and nothing quite so refreshing as a draught of it."[13][2]

Smith also published technical articles on photography.[14]

Personal life[edit]

Smith married Elizabeth Thompson in 1882; the couple had no children.[1] After his father died in 1873, Smith's younger brother, Edmund Reuel Smith (known as "E.R.") inherited the family summer home, the Reuel E. Smith House in Skaneateles, New York.[7]

Smith died at his home at 14 Philipse Place in Yonkers, New York, on November 12, 1935.[15][16]

Collections[edit]

His work is in the permanent collection of the New York Historical Society.[6] The James Reuel Smith Springs and Wells Photograph Collection consists of 17 boxes of materials, including seven boxes of glass negatives as well as acetate negatives.[17] His work is also held in the Library of Congress.[18]

Legacy[edit]

Smith died with an estate worth $328,383 net in 1938 dollars ($6 million in 2021 dollars). Of this, he bequeathed 20 shares (approximately $100,000 in 1938 dollars) to the U.S. government. The remaining shares were given to those he named as heirs including: the American Museum of Natural History; the New York Children's Aid Society; Children's Village Inc. of Dobbs Ferry; Bide-a-Wee Home Association, a "no kill" animal shelter and pet cemetery among other causes.[19]

Contemporary artists' responses[edit]

The works of James Reuel Smith have inspired several contemporary artists who have made works in response to Smith's photographic projects. Jimbo Blachly created a site-specific installation in 2003, About 86 Springs, at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, New York.[20][21] Infrastructure photographer Stanley Greenberg embarked on a project rephotographing all of the well and spring sites in Manhattan and the Bronx. These were published in his 2021 book, Springs and Wells – Manhattan and the Bronx: Stanley Greenberg.[9][22]

Gallery[edit]

-

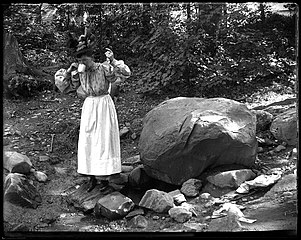

A Woman Drinks at the Carmen Spring, on West 175th Street and Amsterdam Avenue, New York City, by James Reuel Smith, C. 1897-1902

-

Unidentified man drinking from the spring at W. 110th Street, Central Park, 50 feet west of Seventh Avenue, New York City, October 16, 1897

-

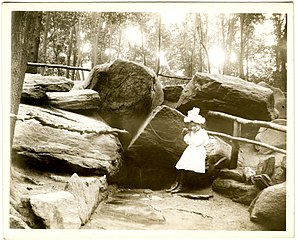

Unidentified girl drinking at Montaigne's Spring, McGown's Pass, Central Park, New York City, July 23, 1898

-

Unidentified girl at the water pump at the rear of 65 E. 87th Street, north side between Madison and Park, New York City, April 21, 1898

-

Unidentified boy at a spring on the northeast corner of Riverside Drive and W. 91st Street, New York City, April 2, 1898

-

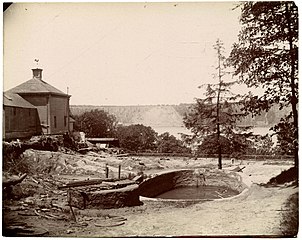

Haven Lane Spring (Buckman's well) between W. 181st and W. 182nd Streets, Northern Avenue and Riverside Drive, New York City, May 31, 1898

-

Unidentified boy using Weissbein's roadhouse pump well, Caton Street, Brooklyn, New York City, November 1, 1898

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Digital Culture of Metropolitan New York – New York Historical Society Collections – Photographs of New York City and Beyond". New York Historical Society. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b New York Historical Society (17 September 2019). "Drink Deep! A Look at Turn-of-the-20th-Century New York's Lost Natural Springs". Urban Archive: New York Historical Society. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (2 July 2006). "City of Angles". The New York Times. ProQuest 433364596. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Steinberg, Ted (2014). Gotham unbound: the ecological history of greater New York. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4767-4124-6.

- ^ Palmer, Matthew I. (April 2015). "Gotham unbound: four centuries of environmental change in America's largest city". Ecology. 96 (4): 1156–1157. JSTOR 43494776. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e Bradley, Henry. "Introducing: the James Reuel Smith Collection from the New-York Historical Society". Urban Archive. Retrieved 1 July 2021.

- ^ a b c d e "Springs And Wells Of Harlem Photographer, James Reuel Smith, 1890 And 1915's". Harlem World Magazine. 26 June 2017. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (4 July 2009). "Manhattan: An Island Always Diverse". The New York Times. ProQuest 434139679. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b Ford, Lauren Moya. "A Photographer Retraces New York's Forgotten Springs and Wells". Hyperallergic. Retrieved 31 July 2021.

- ^ "James Reuel Smith springs and wells photograph collection 1893–1902 – Brooklyn collection". New York Historical Society digital collection. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ a b Smith, James Reuel (1922). Springs and Wells in Greek and Roman Literature. New York and London: G.P. Putnam's Sons. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Smith, James Reuel; Barck, Dorothy C. "Springs and Wells of Manhattan and the Bronx, New York City". New York Historical Society. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Piepenbring, Dan (May 2016). "The Natural Springs of New York City, and Other News". The Paris Review. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Smith, James Reuel (1901). ""A Decimal View Finder"". The International Annual of Anthony's Photographic Bulletin and American Process Year-book. 14: 141–148.

- ^ "U.S. Gets $97,855 in Author's Will". Reading Times (Reading, Pennsylvania). 27 April 1938. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "James R. Smith (obituary notice)". The New York Times. 14 November 1935. ProQuest 101329018. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Unidentified boy at a spring on the northeast corner of Riverside Drive and W. 91st Street, New York City, April 2, 1898". New York Heritage Digital Collections. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Catalog of Public Documents". Library of Congress. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Uncle Sam is left $100,000 In James Reuel Smith's Will: Appraisal Sets Estate at $328,384". The Herald Statesman (Yonkers, New York). 26 April 1938. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Jimbo Blachly: About 86 Springs Dec 14, 2002 – Mar 10, 2003". Sculpture Center. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ Cotter, Holland (13 December 2002). "Prospecting for Clear Springs In the Grittiest Urban Settings". The New York Times. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

- ^ "Inside Art: Springs, Wells, Trees and Shelters with Stanley Greenberg". Brooklyn Public Library. Retrieved 2 July 2021.

External links[edit]

- Drink Deep! A Look at Turn-of-the-20th-Century New York's Lost Natural Springs

- Springs and Wells in Greek and Roman Literature: Their Legends and Locations

- New York Heritage Digital Collection of Photographs by James Reuel Smith

- James Reuel Smith "Springs and Wells" Photographs and Papers at New York Historical Society