Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux

Il n’y a pas d’amour heureux (transl. There Is no Happy Love) is a poem written by Louis Aragon in January 1943, and published in La Diane Française in 1944. The poem reflects on the inherent contradiction between love and the pain that it inevitably brings to those who experience it. An underlying meaning, made explicit in the final stanza, applies this theme to the French Resistance, in which Aragon participated.

History[edit]

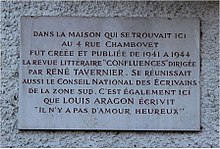

The poem was written in Montchat, a neighborhood in the third arrondissement of Lyon, at the home of Aragon's friend René Tavernier, a fellow poet and resistance member; Tavernier harbored Aragon there during the Occupation along with Aragon's partner Elsa Triolet.[1] The former location of the house, now occupied by Chambovet Park, has been marked since 1993 by a commemorative plaque.[2][3]

In a 1963 interview with Francis Crémieux broadcast on RTF, Aragon explained that at the time he wrote the poem, Triolet intended to leave him due to a Resistance rule that a couple active in the movement could not live together, as this would pose an operational security risk.[4][5][6]

The poem's manuscript was displayed in 1972 at a Bibliothèque nationale exposition on Triolet.[7] René Tavernier's son Bertrand, however, claimed that the poem's original manuscript was still in his father's possession, and that the one displayed at the Bibliothèque nationale was a later copy. The poem was in fact dedicated to his mother Geneviève,[3][8] according to whom Aragon made a second manuscript after the war when the original dedication provoked a quarrel with Triolet.[1][9][10] A facsimile of the Tavernier manuscript was published in 2010 in the review La Règle du jeu.[11]

Adaptations[edit]

Adaptations of the 1950s[edit]

In 1953 the poem, stripped of its final stanza and subjected to minor changes, was set to music and recorded by Georges Brassens, who later reused the same melody for another poem, La prière, by Catholic writer Francis Jammes.[12] Aragon, a lifelong Communist, took offense to this as well as to the abridgment of the poem's conclusion.[13][14] In his estimation, this change altered the entire meaning of his work, which was intended as a poem of the Resistance and not simply a love song. Despite Aragon's objections, the adaptation proved popular and would go on to be covered by such prominent artists as Nina Simone. In 1955, Catherine Sauvage released a recording that reincorporated the final verse.[citation needed]

Other Adaptations[edit]

The work has since been performed by many other artists, including:[15]

- Jacques Douai

- Barbara

- Georges Chelon

- Hugues Aufray

- Nina Simone

- Françoise Hardy

- Keren Ann

- Malek in the album Lhssad (2008)

- Youssou N'Dour

- Danielle Darrieux, in the film 8 Women (2002)

- Élodie Frégé

- Monique Morelli in the album Chansons d'Aragon (1961)

- Marc Ogeret[16]

- Hélène Martin

See also[edit]

- Hedgehog's Dilemma – Metaphor about the challenges of human intimacy

- Le Temps des cerises – another well-known French song/poem with a similar dual theme

References[edit]

- ^ a b Tavernier, Bertrand; Simsolo, Noël [in French] (2011). Le cinéma dans le sang: Entretiens avec Noël Simsolo [Cinema in the Blood: Interviews with Noël Simsolo] (in French). Paris: Écriture. ISBN 978-2-35905-036-3..

- ^ Ferenczi, Aurélien [in French] (July 18, 2008). "Bertrand Tavernier habitait au 4, rue Chambovet, à Lyon". Télérama.

- ^ a b Thévenon, Bruno (10 July 2013). "Confluences, Tavernier, Aragon et les autres". Le Progrès.

- ^ "Louis Aragon : 6ème partie" [Louis Aragon: Part 6]. Inathèque. Entretiens avec. Institut national de l'audiovisuel.. Can be viewed at "Louis Aragon (6/10) : Il y aurait des amours heureuses" À voix nue, France Culture, November 17, 2020 (begins at 13:50).

- ^ Entretiens avec Francis Crémieux: Le fou d'Elsa, l'écoulement du temps, la ponctuation, l'équivoque, le réalisme, le roman, Elsa, et autres sujets [Interviews with Francis Crémieux: Elsa's Fool, the Flow of Time, Punctuation, Ambiguity, Realism, the Novel, Elsa, and Other Subjects]. Paris: Gallimard. 1964. p. 98. BNF 37449108.

- ^ Desanti, Dominique (1983). Les Clés d'Elsa [Elsa's Keys]. Paris: Ramsay. p. 312. ISBN 2-85956-331-8..

- ^ Beaudiquez, M., Massuard, A., Avril, M., Bibliothèque nationale (1972). Elsa Triolet : [exposition], Paris, [Bibliothèque nationale, 10 février-30 mars] 1972. Bibliothèque nationale. p. 16. BNF 35367007.

- ^ Guichoux, Marie (12 March 1999). "Bertrand Tavernier, la lutte filmale". Libération.

- ^ Douin, Jean-Luc (1988). Tavernier. Cinégraphiques (in French). Paris: Édilig. pp. 75–76. ISBN 2-85601-185-3.

- ^ Douin, Jean-Luc (2006). Bertrand Tavernier: Cinéaste insurgé [Bertrand Tavernier: Insurgent Filmmaker]. Ramsay poche cinéma (in French). Paris: Ramsay. p. 108. ISBN 2-84114-813-0.

- ^ Corpet, Olivier (May 2010). "La leçon d'Aragon". La Règle du jeu. 20 (43).

- ^ "Album 'Chanson pour l'Auvergant'". Analyse Brassens.

- ^ Chaline, Thomas (2021). Brassens: une vie en chansons [Brassens: a Life in Songs] (in French). Paris: Hugo Doc. ISBN 978-2-7556-9218-1.

- ^ Winter, Jean-Pierre (2019-04-25). "« Et quand il croit serrer son bonheur, il le broie »" ["And when he believes he embraces his happiness, he crushes it"]. Vous avez dit jouissance ? [You Said Enjoyment?]. Érès. pp. 245–257. doi:10.3917/eres.guily.2019.01.0245. Retrieved 2022-01-02.

- ^ "Il N'y A Pas D'amour Heureux (1953)". All versions of Some musics. 23 January 2011..

- ^ DYM AND DESTROY (2012-11-20). "Marc Ogeret - Il n'y a pas d'amour heureux (Aragon)".