Helen Appo Cook

Helen Appo Cook | |

|---|---|

Appo Cook in 1898. | |

| Born | Helen Appo July 21, 1837 New York, United States |

| Died | November 20, 1913 (aged 76) Washington, D.C., United States |

| Occupation(s) | women's club leader, community activist |

| Spouse | |

| Children | 5 |

| Parent(s) | William Appo Elizabeth Brady |

Helen Appo Cook (July 21, 1837 – November 20, 1913) was a wealthy, prominent African-American community activist in Washington, D.C., and a leader in the women's club movement. Cook was a founder and president of the Colored Women's League, which consolidated with another organization in 1896 to become the National Association of Colored Women (NACW), an organization still active in the 21st century.[1] Cook supported voting rights and was a member of the Niagara Movement, which opposed racial segregation and African American disenfranchisement.[2] In 1898, Cook publicly rebuked Susan B. Anthony, president of the National Woman's Suffrage Association, and requested she support universal suffrage following Anthony's speech at a U.S. Congress House Committee on Judiciary hearing.[3][4]

Early life[edit]

Helen Cook was born to William Appo, a prominent musician, and Elizabeth Brady Appo, who owned a millinery business in New York.[5] Because of William Appo's music career, the family lived in various cities, such as Baltimore and Philadelphia before settling permanently in New York.[6]

As a teenager, Helen Cook attended meetings about women's rights with her mother. She self-identified with the women's cause:

I was born to an inheritance of appreciation and sympathy for the cause of women's rights, my mother before me being so ardent a supporter of its doctrines that I felt myself, in a measure, identified with it. Among my earliest recollections are the Sunday afternoon meetings, held at the home of Lucretia Mott, on Arch street, in Philadelphia... on one of those occasions...I heard that eloquent advocate of human freedom, the English abolitionist, George Thompson.[3]

As an adult, Cook attended the first suffrage convention held in Washington, D.C., in January 1869 and organized by the Universal Franchise Association.[3]

Leadership and activism[edit]

National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children[edit]

In 1864 the National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children was incorporated by an act of the United States Congress to provide "suitable home, board, clothing, and instructions, and to bring them under Christian influences".[7] Elizabeth Keckley, seamstress and confidant to former first lady Mary Todd Lincoln, was one of the founding association member.[8] Helen Cook was a member for nearly 35 years and held various leadership positions. In 1880, she was the first African-American woman to be elected secretary of the association, a position she held for ten years.[9][10] African-American men also supported the association. Frederick Douglass paid for life membership in 1866. Dr. Charles B. Purvis and James Wormely, an owner of the Wormley's Hotel in Washington, D.C., joined the Board of Trustees in 1872. John F. Cook, Jr., Helen Cook's husband, joined the board in 1885, provided financial assistance, and helped influence Congress for continued funding.[11] Congressional appropriations, though, ended in 1892.[8] The Association maintained a building for people without housing and orphans at Eighth and Euclid Streets, Northwest, with standing committees on Admission and Dismission, Household Management, Education, and Clothing. At the time of her death, Helen Cook was President of the association.[12]

Colored Women's League[edit]

In 1892, Helen Cook, Ida B. Wells, Anna Julie Cooper, Charlotte Forten Grimké, Mary Jane Peterson, Mary Church Terrell, and Evelyn Shaw formed the Colored Women's League in Washington, D.C. The goals of the service-oriented club were to promote unity, social progress, and the best interests of the African-American community. Helen Cook was elected president.[13]

Cook wrote the first "Washington Letter" about the activities of the Colored Women's League (CWL) in The Woman's Era (1894–1897), the first national newspaper published for and by African American women.[14] Cook shared the CWL's 1894 accomplishments that included raising $1,935 towards a permanent league home; hosting a series of public lectures for girls at a local high school and at Howard University; establishing CWL-sponsored classes in German, English literature and hygiene; the establishment of a sewing school and mending bureau with 88 students and ten teachers; the payment of tuition for two nursing students and part salary to hire a kindergartner teacher.[15] CWL member Mary Church Terrell provided subsequent updates from Washington, D.C., league efforts to the newspaper.[16]

In May 1898, Helen Cook spoke at the Second Annual Convention of the National Congress of Mothers, held in Washington, D.C. The National Congress of Mothers was the forerunner to today's National Parent Teachers Association. In her speech "We Have Been Hindered: How Can We Be Help?", she denounced those who identify negative behavior traits as inherent among African-American instead of looking at the negative traits as a response to the effects of poverty and prejudice.[17] W.E.B. DuBois also appeared at the Congress of Mothers Conference and, on May 6, presented a paper titled "The History of the Negro Home".[18][19]

Later in 1898, W.E.B. DuBois invited Helen Cook to submit a paper for the third annual Atlanta Conference of Negro Problems held at Atlanta University.[20] The purpose of the conference series (1896–1914) was to identify difficulties the African American community faced and suggest solutions. Others invited to submit papers included Rev. Henry Hugh Proctor of First Congregational Church (Atlanta, Georgia), journalist and attorney Lafayette M. Hershaw, and Miss Minnie L. Perry, board member of the Carrie Steele Orphanage. Helen Cook's paper outlined the accomplishments of the CWL, including the enrollment of more than 100 children in its kindergartens.[21]

Over time, the Colored Women's League established a training center for kindergarten teachers and maintained seven free kindergartens and several day nurseries.[22] The league also established sewing schools, night schools and penny-saving banks.[23]

By 1903, the league had a permanent building at 1931 12th Street, Northwest, which offered temporary room, board, and a day nursery.[24] Additionally, with Helen Cook still the elected president, the organization had the largest membership of any African American women's club in the country, according to historian Fannie Barrier Williams.[25]

League members envisioned a national organization from its inception, according to an 1893 article by founding member Mary Church Terrell. "The Colored Women's League recently organized in Washington has cordially invited women in all parts of the country to unite with it so that we may have a national organization," she wrote.[26]

First National Conference of Colored Women of America[edit]

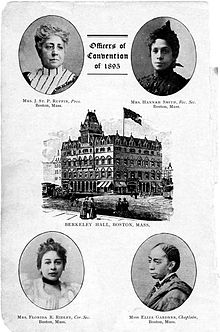

Historical Records of Conventions of 1895-96 of the Colored Women of America][27]

In 1895, Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, president of the Woman's Era Club of Boston, invited all African American women to convene for a three-day conference in Boston to discuss critical issues related to Black women's "moral, mental, physical and financial growth and well-bring" following disparaging remarks about the character of African American women by John Jacks, president of the Missouri Press Association.[1][28]

The Colored Women's League and twenty-four other clubs nationally attended the First National Conference of Colored Women of America July 29–31, 1895. Officers of the Convention were responsible for making conference arrangements and included Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, president; Mrs. Hannah Smith, recording secretary, Mrs. Florida Ruffin Ridley, corresponding secretary, and Miss. Eliza Gardner, chaplain.[1] Elected convention officers included Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin, president; Helen A. Cook and Margaret Murray Washington, vice-presidents; Eliza Carter and Mrs. Hannah Smith, secretaries.[1][29]

On the convention's first day, Helen Cook gave an address titled "The Ideal National Union", calling for unity and outlining the goals and purpose of a national organization supporting Black women.[29][30][31] Cook also spoke about a vision for a national organization on the last day of the conference. Mrs. Victoria Earle Matthews presented a resolution to form a national organization. An additional day was added to the convention and held at Charles St. Church to discuss creating a national organization. The resolution passed, and a committee was formed to work through the details of a national organization.[1]

Second National Conference of Colored Women of America[edit]

A year later, African-American women's clubs from across the country gathered in Washington, D.C., for a convention of the National Federation of Afro-American Woman with Mrs. Booker T. Washington presiding. On July 20, 1896, the second day of the convention, a motion passed for a committee to create a union between the National Federation of Afro-American Women and the Colored Women's League. The new organization, the National Association of Colored Women, elected Mary Church Terrell as its first president.[1]

Admonishing Susan B. Anthony[edit]

On February 15, 1898, the House Committee on Judiciary heard from representatives of the National Woman's Suffrage Association (NWSA) on a proposition to amend the United States Constitution and grant women's suffrage. Women's rights activist and NWSA president Susan B. Anthony spoke at the hearing of "ignoramuses who held the elective franchise".[4] Anthony suggested the proposed Fifteenth Amendment, which would give citizens the right to vote, regardless of race, color, or previous condition of servitude, humiliated [white American] women. Anthony said, according to one news account, "[T]he ballot ...is put in the hands of every man outside the State Prison, whether they have sufficient sense to cast their ballots or not, yet the women of the country were compelled to humiliate themselves in pleading for rights that should have been accorded them long ago."[4] Anthony continued and "drew comparisons between many of the ex-slaves and the large number of women of high intellectual rank compelled to acknowledge their political inferiority to these".[4]

Days later, Helen Cook responded "with pained surprise" to Susan B. Anthony's congressional testimony through a letter published in The Washington Post outlining Cook's history engaged with women's rights.[3] Cook appealed to Anthony to promote the cause of universal suffrage over disparaging "a noble manhood" or African American men.[3] Cook noted Anthony's "great influence with other women...[and] power to direct their thoughts and endeavors" and suggested Anthony support universal suffrage before negative views about Black men and their suffrage gained greater popularity.[3]

Niagara Movement[edit]

At nearly seventy years old, Helen Cook and her husband, John F. Cook, Jr., traveled to Harpers Ferry, West Virginia to attend the August 1906 national meeting of the Niagara Movement.[32] The Niagara Movement (1905–1910) was an African American civil rights organization founded a year earlier by W. E. B. Du Bois and William Monroe Trotter to oppose racial segregation and African American disenfranchisement.[33] John Cook attended as a member of the organization. At the meeting, after debate, it was decided women could become associate members, and Helen Cook became an associate member.[34]

Marriage and children[edit]

Helen and John Francis Cook, Jr. married in 1864. He became the wealthiest African American resident in Washington, D.C., with a reported worth of $200,000 in 1895. His professional endeavors included an appointment as D.C.'s chief tax collector (1874 to 1884), serving as a trustee of Howard University (1874-1908), and partnering with his brother, George F. T. Cook, and former congressman George Henry White in the firm Cook, Cook and White, which manufactured bricks from 1904 to 1906.[35]

The Cooks had five children, including Elizabeth Appo Cook (1864–1953), John Francis Cook, III (1868–1932), Charles Chaveau Cook (abt 1871–1910), George Frederick Cook (1874–1927), and Ralph Victor Cook (1875–1949).[36]

Death[edit]

Helen Cook died from pneumonia and heart failure on November 20, 1913, in Washington, D.C., at the family Cook residence (1118 Sixteenth Street, Northwest).[36] One African American newspaper noted that she was "easily the wealthiest colored woman in the District of Columbia. The Cook estate has been considered to be worth not less than a quarter of a million dollars...Mrs. Cook was greatly interested in Negro organizations and charity work and was a woman of kindly heart and broad sympathies."[37] Cook was buried at Columbian Harmony Cemetery, along with her late husband, John F. Cook, Jr. and other Cook family members.[38] The law firm Carlisle, Luckett & Howe handled Cook's estate.[39]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f "Historical Records of Conventions of 1895–96 of the Colored Women of America" (PDF). University of Chicago Library. 1902. Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Carle, Susan D (2015). Defining the struggle: national organizing for racial justice, 1880–1915. Oxford University Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9780190235246. OCLC 907510485.

- ^ a b c d e f Gordon, Ann D. (2013). The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony: An Awful Hush, 1895 to 1906. Rutgers University Press. p. 204. ISBN 9780813553450.

- ^ a b c d "Women Plead for Equal Suffrage". The Times. Philadelphia, PA. February 16, 1898. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 6, 2019. Retrieved August 6, 2019 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ "Mrs. E.A. Appo. Plain and Fashionable Milliner and Dress Maker". New York Colored American. July 11, 1840.

- ^ Smith, Jessie Carney (1996). "Helen Cook". Notable Black American women: book II. Gale Research. p. 138. ISBN 9780810391772. OCLC 960050891.

- ^ First annual report of the National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children. McGill & Witherow. 1864. p. 6. OCLC 255405778.

- ^ a b "Merriweather Home for Children/Elizabeth Keckly, African American Heritage Trail". culturaltourismdc.org. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Twenty-fourth annual report of the National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children, for the year ending January 1, 1887 ..." Library of Congress. Archived from the original on July 17, 2019. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ "Image 5 of Thirty-seventh annual report of the National Association for the Relief of Destitute Colored Women and Children, for the year ending January, 1900 ..." Library of Congress. Retrieved July 17, 2019.

- ^ Mjagkij, Nina (2013). Organizing Black America. Routledge. p. 328. ISBN 9781135581237.

- ^ Plummer, Nellie Arnold (1997). Out of the depths, or, The triumph of the cross. G.K. Hall ; Prentice Hall International. pp. 218–223. ISBN 9780783814254. OCLC 36817196.

- ^ Smith, Jessie Carney (1992). "Josephine Beall Bruce". Notable Black American women (v1 ed.). Gale Research Inc. p. 123. ISBN 9780810347496. OCLC 34106990.

- ^ The woman's era, vol.1, no.1 (March 24, 1894). Ruffin, Josephine St. Pierre; Ridley, Florida R. (Florida Ruffin); Baldwin, Maria.

- ^ "EWWRP : Women's Advocacy Collection : The Woman's Era, Volume 1 : Club News 0". womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ "EWWRP: Women's Advocacy Collection: Women's Era". womenwriters.digitalscholarship.emory.edu. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Report of the Proceedings of the Second Annual Convention of the National Congress of Mothers, Held in the City of Washington, D.C., May 2nd-7th, 1898. Philadelphia, PA: Geo. F. Lasher. 1899. p. 50.

- ^ Farland, Maria (2006). "W. E. B. DuBois, Anthropometric Science, and the Limits of Racial Uplift". American Quarterly. 58 (4): 1017–1045. doi:10.1353/aq.2007.0007. ISSN 0003-0678. JSTOR 40068404. S2CID 145448171.

- ^ "The bulletin of Atlanta University - On the Campus". hbcudigitallibrary.auctr.edu. p. 1. Archived from the original on July 21, 2019. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (1994). W. E. B. Du Bois, 1868-1919: Biography of a Race. Henry Holt and Company. p. 219. ISBN 9781466841512. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ DuBois, W.E.B. (May 25, 1898). Some Efforts of American Negroes for Their Own Social Betterment (Third Conference for the Study of the Negro Problems ed.). Atlanta University: Atlanta University Press. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Lerner, Gerda (1974). "Early Community work of Black Club Women". The Journal of Negro History. 59 (2): 162. doi:10.2307/2717327. JSTOR 2717327. S2CID 148077982.

- ^ Kletzing, H. F; Crogman, W. H (1987). "Club Movement Among Negro Women". Progress of a race, or, The remarkable advancement of the Afro-American Negro from the bondage of slavery, ignorance, and poverty to the freedom of citizenship, intelligence, affluence, honor and trust. Atlanta, GA: J.L. Nichols & Co. p. 207. OCLC 1013367734.

- ^ "For Charity's Sake: Benevolent Women of the Nation's Capital Work for Sweet Charity's Sake - The Election of Officers". The Colored American. Washington, D.C.: 10 January 31, 1903.

- ^ Kletzing, H. F; Crogman, W. H (1987). "Club Movement Among Negro Women". Progress of a race, or, The remarkable advancement of the Afro-American Negro from the bondage of slavery, ignorance, and poverty to the freedom of citizenship, intelligence, affluence, honor and trust. Atlanta, GA: J.L. Nichols & Co. p. 207. OCLC 1013367734.

- ^ Leslie, LaVonne Jackson (2012). History of the National Association of Colored Women's Clubs, inc.: a legacy of service. Xlibris. p. 29. ISBN 9781479722631. OCLC 821218626.

- ^ "Historical Records of Conventions of 1895-96 of the Colored Women of America" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on May 19, 2016. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ Hendricks, Wanda A. (1998). Gender, Race, and Politics in the Midwest: Black Club Women in Illinois. Indiana University Press. p. 18. ISBN 9780253334473. Retrieved July 18, 2019.

- ^ a b "COLORED WOMEN IN CONFERENCE; National Association for Their Betterment Formed in Boston". timesmachine.nytimes.com. July 30, 1895. p. 6. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Smith, Jessie Carney (1996). "Helen Appo Cook". Notable Black American women book II book II (v2 ed.). Gale Research. p. 139. ISBN 9780810391772. OCLC 960050891.

- ^ "Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin: A pioneer in the black women's club movement". The Bay State Banner. February 3, 2016. Archived from the original on July 20, 2019. Retrieved July 20, 2019.

- ^ Carle, Susan D (2015). Defining the struggle: national organizing for racial justice, 1880–1915. Oxford University Press. pp. 200–201. ISBN 9780190235246. OCLC 907510485.

- ^ Jones, Angela (2011). African American Civil Rights: Early Activism and the Niagara Movement. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9780313393617. OCLC 751692272.

- ^ Carle, Susan D. (2015). Defining the Struggle: National Organizing for Racial Justice, 1880-1915. Oxford University Press. p. 200. ISBN 9780190235246. Retrieved July 21, 2019.

- ^ Justesen, Benjamin R (2012). George Henry White: an even chance in the race of life. Louisiana State University Press. p. 377. ISBN 9780807144770. OCLC 809766906.

- ^ a b Smith, Jessie Carney (1996). "Helen Appo Cook". Notable Black American women book II book II (v2 ed.). Gale Research. pp. 137–138. ISBN 9780810391772. OCLC 960050891.

- ^ "Mrs. Helen A. Cook Passes Away". The Freeman (Indianapolis, IN): 1. November 29, 1913.

- ^ Major, Gerri; Saunders, Doris (1976). Gerri's Major's Black Society. Johnson Publishing Company Inc. p. 230.

- ^ "Legal Notices". The Washington Post. June 19, 1914. p. 13.

External links[edit]

- Cook Family Papers, Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University, Washington, D.C.

- National Association of Colored Women's Club

- Genealogy of the Cook Family of Washington, D.C., by Stanton L. Wormley.