H. E. and A. Bown

| H. E. and A. Bown | |

|---|---|

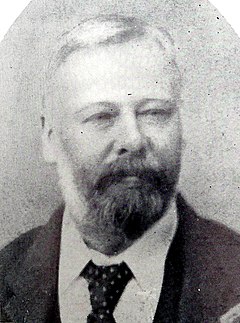

Arthur Bown, in 1902 | |

| Practice information | |

| Firm type | Architectural partnership |

| Partners |

|

| Founded | After 1868 |

| Dissolved |

|

| Location | Harrogate, North Riding of Yorkshire, England |

| Significant works and honors | |

| Buildings |

|

H. E. and A. Bown was an architectural practice in Harrogate, North Riding of Yorkshire, England, in the 19th and early 20th centuries. Its two partners were Henry Edwin Bown who started the business and died at the age of 36, and his brother Arthur Bown, who carried on the business until he retired in 1911.

The firm produced designs for many of Harrogate's villas, especially those in the West Park and Victoria Park estates, the Jubilee Memorial, Harrogate, and Queen's Park Lodge and fountain, Heywood, Greater Manchester, besides The Harrogate Club house, and Harrogate's drill hall. Many of their works are still standing, and the Jubilee Memorial and Queen's Park Lodge and fountain are listed buildings.

Background of the partners[edit]

The two partners of the architectural practice H. E. and A. Bown of Harrogate, West Riding of Yorkshire, were brothers who came from an artisanal background, of Northern England and Midlands stock. Their paternal grandparents were jeweller Peter Bown (1791–1872) born in Matlock, Derbyshire, and Mary Fielding (1785 – 18 June 1881),[1] also from Matlock.[2][3] Their parents were jeweller and china-dealer Edwin Bown (c.1823–1909),[4][5][nb 1] born in Buxton, Derbyshire, and Anne Bown (c.1823–1891),[4][nb 2] from Skircoat Green, near Halifax, West Yorkshire.[6] Ann Bown is listed as an architect in the 1861 Census, however Henry Edwin was a 16-year-old apprentice architect by that time but is listed as a scholar, when boys were schooled up to age 14, so that may be a line-slippage error.[7]

Henry Edwin Bown[edit]

The elder brother was Henry Edwin Bown, who was born in Halifax on 26 March 1845,[8][9][nb 3] but spent his professional years in Harrogate.[10] In 1870 at Knaresborough, he married Sarah Margaret Husband (1849–1899), born in Batley, West Yorkshire, whose father was chemist and druggist James Husband of Batley.[8][11][nb 4] They had three children: architect Percival "Percy" Bown (1873–1953),[12][nb 5] Frank (1876 – 8 June 1929)[13] and Kathleen Carr née Bown (born 1877),[14] all born in Harrogate.[15] H. E. Bown was a member of the Harrogate Horticultural and Floral Society, and would show his roses at its annual flower show: sometimes under the name of his gardener John Pinkney, sometimes under his own name.[16]

From 1877, during the last four years of his life, H. E. Bown spent much time away from his work, attempting relief from tuberculosis, in Bournemouth and Italy.[10] He died in Harrogate on 27 September 1881 after suffering a "long and trying illness".[10][17] The funeral took place on 29 September, and he was buried in Grove Road Cemetery, Harrogate, beside the family's vault where his grandfather Peter Bown lay. The funeral cortège was "headed by a number of gentlemen of the town". It travelled via Beech Grove from his home, Harlow View, to the cemetery, where many mourners had gathered with Rev. G. O. Brownrigg, who took the service. "The coffin (which was of polished oak and gilt furniture) was almost covered with wreaths, and bore upon the breastplate the following inscription: 'Henry E. Bown, died Sept. 27th, 1881, aged 36 years'".[10]

Sarah Margaret Bown, left with three young children, did not remarry; she died a widow in Boston Spa on 22 January 1899, aged 49 years.[18] The Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald said:[10]

To few men does Harrogate owe more than to the lamented [H. E. Bown]. Talented in his profession, endowed with consummate taste and enterprising spirit, he has devoted his life to the manifest improvement of his town, converting wild waste into cultivated order, and barren plots into beauty and fertility.[10]

Arthur Bown[edit]

The younger brother was Arthur Bown, who was born on 22 January 1851 in Harrogate.[4][19][20][nb 6] He attended school at Knaresborough.[20] His father-in-law was in a trade complementary to his own, making decorative iron railings among other things. At Hick Lane Welseyan Chapel, Hick Lane, Batley on 29 December 1880 Arthur Bown married Jane "Janie" Bagshaw (1857–1917),[4][21][nb 7] whose father was Batley iron founder and engineer John Bagshaw (c.1828–1897) of Stockwell House, Batley.[4][20][nb 8] The couple honeymooned in Torquay.[22] One of their two children was Harrogate architect Harold Linley Bown (1883–1962).[4][23][nb 9] who in 1935 designed a cinema with frontages in Cambridge Road and Oxford Street and adjoining St Peter's Church, Harrogate (since demolished).[24]

Between 1891 and 1916, Arthur Bown's residence was "Hillstead", 11 Grove Road, Harrogate, West Yorkshire.[4][20] Bown died in Harrogate on 3 July 1916. He was buried on 5 July in Grove Road Cemetery,[4] after a service at St Luke's Church, Harrogate.[25] He left £7,092 (equivalent to £511,569 in 2021) gross.[26][27]

Training, partnership and assistants[edit]

Training[edit]

Henry Edwin Bown was articled to architect Richard Dyson of Harrogate. In 1868 he was elected ARIBA,[8] "and early showed marked adaptability for his profession". He was then employed as an assistant to the architect William Hill of Park Square, Leeds. Subsequently, he founded his own practice in Harrogate, "where the high character of his work raised him to a position of importance".[10]

Having been "originally intended for an engineer",[20] Arthur Bown was apprenticed with a Mr Barron, C.E., of Leeds, then with Manning Wardle at Boyne Engine Works in Hunslet, Leeds.[nb 10] After that, he served two years as an improver at the architectural firm of J. Douglas Matthews in London.[4] Thereafter he "erected numerous public and private buildings".[20]

Partnership[edit]

Henry Edwin Bown started the practice alone under the name H. E. Bown from around 1868, working from Beulah House, Chapel Street, Harrogate (1868–1870), then Victoria Buildings, James Street, Harrogate (1871–1881).[8][28] In 1877 Arthur Bown joined in partnership with his brother Henry as H. E. and A. Bown.[4][20][nb 11] Although the partnership was dissolved in 1881 after Henry died,[29] Arthur Bown continued under the original practice name until he retired in 1911.[4] The firm was still trading out of James Street in 1899.[30]

In 1895 Arthur Bown brought a case against engineer W. H. Baxter of Leeds, in that Baxter had not paid Bown for surveying and architectural work carried out on Baxter's stables and residence in Knapping Mount, Harrogate. Baxter counterclaimed for unskilled and improper services on the part of Bown. The case went to arbitration, both were allowed their monetary claims, and Bown had to pay the difference between the sums claimed.[31][32]

Assistants[edit]

One of at least three assistants to Arthur Bown was George R. Bland (b.1866) (fl.1894–1896), who was with the firm between 1885 and 1894. He was later working in partnership as Bland & Bown, with T. Bown, and then H. E. Bown's son Percival Bown. Percival Bown was also articled to Arthur Bown, between 1890 and 1894, and was his assistant until 1897. A third assistant, taken on in 1901, was Walter Clement Barker (1880–1854).[33]

Works: new builds, 1860s – 1881[edit]

After H. E. Bown died in 1881, the Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald credited him with the following works (although some may have involved collaboration with his brother):[10]

Dunorlan, the Colonnade at the Spa, Duchy House, the Congregational Schools, most of the houses on the Franklin Estate, of which he was the founder, and many of the handsome residences of Victoria Park; besides which he laid out the estate of the West End Park Co.[10]

West End Park and Victoria Park, Harrogate, 1870[edit]

According to the Whitby Gazette's article "Progress of Harrogate" in 1870:[34]

The West End Park, situate opposite the Prince of Wales Hotel, now forms a formidable rival to the Victoria Park. The premium offered by the company, who bought 69 acres here, for the best plan for laying out the estate with sites and first-class villas, was awarded to [John Henry Hirst (1826–1882)],[nb 12] of Bristol, architect. Either a second premium was awarded to Mr H. E. Bown, or an arrangement was come to whereby it was agreed that Mr Hirst should take the premium, and Mr Bown carry out the design. However, Mr Bown appears to have the principal management of the estate. There are above 300 sites, we believe, including a site for a church. Many of the mansions in Victoria Park have also been designed by Mr Hirst and Mr Bown.[34]

Congregational pastor's manse, West End Park, 1870[edit]

This manse in West End Park, adjoining the Leeds Road, was designed by Henry Edwin Bown, at a cost of £1,300 (equivalent to £132,332 in 2021).[26][35] The foundation stone was laid on 17 August 1870 by theological writer Rev. Eustace Conder of East Parade Chapel, Leeds.[35][36] It was designed with "two large bay windows in front, with drawing room, dining room, library etc., with bedrooms and offices ... the house [stood] in its own grounds, and [commanded] extensive views of the Vale of York". The first pastor of the church to inhabit the manse was to be Rev. F. Fox Thomas.[35]

Former detached villa, Station Parade, Harrogate, 1870s[edit]

This was a Gothic Revival villa on Station Parade, Harrogate, North Riding of Yorkshire, England, designed for the developer Victoria Park Company, by Henry Edwin Bown. The crosses on the gable suggest that it may have been a priest's house for St Robert's Church, Harrogate (built 1873) across the road. It was demolished in the 1980s to make way for a Safeways supermarket. A Waitrose supermarket occupies the site, as of 2022.

Queen's Park Lodge and fountain, Heywood, Greater Manchester, 1878–1879[edit]

This lodge, designed by H. E. and A. Bown in 1878,[4] and opened on 9 August 1879,[37] is a listed building.[38] Queen Victoria donated the money for Queen's Park and its buildings for the benefit of the inhabitants of Heywood,[39] hence the lodge is sometimes described as having been built for the Queen.[4] It was originally designed as the main entrance lodge for Queen's Park, Heywood, Greater Manchester. It is described by Historic England as follows:[38]

A second entrance lying to the north of the main entrance [of Queen's Park] gives access to a timber-framed and tile-hung lodge (c.1879) designed by Messrs Bown,[nb 13] architects, of Harrogate ... This was intended to be the main entrance but the main access was changed as part of the redesign of the park in the 1930s.[38]

British Architect described the building in 1879 thus:[39][40]

The walls up to the first floor are constructed of pitch faces (sic) delph stones and above that in half-timber and cement. The gables are filled in with tile hanging, and the roof is covered with chocolate-coloured Staffordshire tiles. The interior woodwork and fittings are in pitch pine.[39][40]

The firm is also credited with the 1878–1879 design of a "grand three-basin ornamental fountain, elaborately decorated with dolphins and swans",[41] at Queen's Park.[29][42] The fountain is a listed building, included in the same listing as the lodge above, although Historic England has spelled Bown's name incorrectly.[38]

Detached house, Holderness Road, Hull, 1880[edit]

This house was designed for Frederick J. Reckitt by H. E. and A. Bown, but since Henry Edwin Bown was ill by this time, the project architect was probably Arthur Bown.[43]

Dunorlan, 2 Park Road, Harrogate, before 1881[edit]

This large villa was designed by Henry Edwin Bown, possibly in collaboration with his brother Arthur.[10] As of 2022 it had been converted into flats.[44]

Works: new builds, 1882 – 1911[edit]

Note: The following works were designed or completed by Arthur Bown, after his brother died in 1881.

Bradford Old Banking Company building, James Street, Harrogate, 1885[edit]

This former building designed by Arthur Bown was a replacement of the bank's previous, less convenient, building on the opposite side of the road.[45] It was built on the former site of Vina Villa, and stood at the junction of James Street and Princes Street, Harrogate. It was demolished in 1938 to make way for a branch of Barclays Bank which still stands as of 2022.[46]: 33, 34 The bank's board chose H. E. and A. Bown ...[45][47]

... under whose plans one of the most magnificent and imposing buildings in the town has been erected. Both internally and externally the premises have an elaborate appearance. The building is entirely of stone, carved. The fittings are of polished mahogany, every convenience being provided. The strong room of the bank has had special attention paid, being made practically burglar and fire-proof, and is fitted with Chubb's doors the room being about 24 feet square. The buildings are a decided improvement to the town, and have been much admired while in course of erection, special care having been taken in the external carving, &c.[45]

The Harrogate Club house, Harrogate, 1885–1886[edit]

This unlisted building was designed by Arthur Bown as a club house for The Harrogate Club in 1885, and completed at 36 Victoria Avenue, Harrogate, in 1886.[48][49][50] Historian Malcolm Neesam describes it as follows:[51]: 48–50

[It] stands imperiously ... at 36 Victoria Avenue, its superb frontage seemingly a contradiction of the institution's modern and welcoming character. Outside, an essay in high Victorian exclusiveness, with a raised ground floor reached by a mountain of wide stone steps, and a massive front door flanked by a pair of the finest curved glass windows in Yorkshire ... a noble building ... a landmark in the town ... with its lofty staircase, illuminated by a huge window of beautiful painted glass. [Upstairs, the largest room in the Club] is the great chamber for billiards and snooker, its high glass ceiling carried aloft with wonderful wooden trusses in the Gothic style.[51]: 48–50

Jubilee Memorial, Harrogate, 1887[edit]

This monument consists of a "statue of Queen Victoria below [a] stone canopy" in "Gothic style" in celebration of her Golden Jubilee. It is a listed building,[52] and was designed by Arthur Bown.[4] The marble statue within it was sculpted by W. J. S. Webber. Although H. E. Bown died a few years before the Jubilee Monument was formally opened, the local newspapers credited him along with his brother Arthur for his share in the architectural design, because Arthur Bown continued to use the practice name.[4][53] When the Mayoress of Harrogate, May Jane Ellis, laid the cornerstone of the memorial, Arthur Bown presented her with an engraved silver trowel, engraved thus:[54][55]

Presented to the Mayoress of Harrogate (Mrs Ellis) by the architects and contractor, on the occasion of her laying the cornerstone of Her Majesty's Jubilee Memorial, Station Square, Harrogate, April 14th, 1887.[54]

House for Mr M. Stephenson, near Pannal Ash[edit]

In November 1889, this Tudor Revival house, designed by Arthur Bown, was in the process of construction for M. Stephenson, in Pannal Ash Road, near Pannal Ash, between Otley and Blythe Nook. It was "placed in the centre of park-like grounds of about ten acres in extent laid out and planted". The house entrance was on the south side, and the building was "designed in the Domestic Tudor or what is sometimes also termed Old English style of architecture". Although the interior was intended to match the period style of the exterior, it was "modified to suit the requirements of the 19th century". Ninety people, including all the site workmen, sat down to a dinner, with toasts and speeches, provided by Stephenson at the Prospect Hotel, Harrogate, to celebrate the work while still in process of completion. Among others, Arthur Bown gave a speech in which he mentioned the good relationship between workers, and architect.[56]

Drill Hall, Harrogate, 1894[edit]

This drill hall was designed by Arthur Bown at a cost of £2,300 (equivalent to £278,623 in 2021) for the use of F Company of the 1st VB West Yorks (PWO) Regiment, which previously had to "drill in the street".[26] The foundation stone was laid on 22 May 1894 at the junction of Strawberry Dale and Franklin Road,[nb 14] by Colonel George Kearsley,[nb 15] commander of the regiment, before a large crowd including military and civic personages, and with some ceremony including a military band. The hall alone measured 91 ft × 48 ft (28 m × 15 m), and the building included an orderly room, an armoury, lavatories, a cellar and band room in the basement, and a gymnasium upstairs. The club rooms above the hall were reached via the tower, and included a reading room, a smoking room and a billiard room. There was also a three-bedroom sergeant's house.[57] The building has the insignia of the West Yorkshire Regiment carved into the top of the gable.[58]

Two shops in James Street, Harrogate, 1896[edit]

Arthur Bown designed two shops and made alterations to a property in James Street, Harrogate in 1896.[59]

Factory, offices and stables, Manchester, 1896[edit]

In 1996, Arthur Bown was calling for building contractors, to build a factory, offices and stables in Stockport Road, Manchester, for the Chemists′ Aerated Mineral Waters Association Limited.[60]

Salvation Army Barracks, Harrogate, 1897[edit]

The eight memorial stones (or foundation stones) for this building were laid on 23 January 1897, on the former site of Volta House and garden, Harrogate. The stones were laid by several local worthies, including the Mayor of Harrogate, Councillor J. H. Wilson, in the presence of a "large attendance" including various significant local personages and Salvation Army officers. All those who laid the stones were presented with a trowel and inscribed mallet by the contractor Rhodes of Shipley, and Arthur Bown who designed the building. The plans included shops, cellars, a large hall to accommodate 500 people and a junior soldiers' room for 100, retiring rooms, officers' rooms, a crush room, and a band room.[61]

7 and 8 Springfield Avenue, Harrogate, 1898[edit]

This pair of semi-detached villas was designed by Arthur Bown, "showing the same strong neo-Tudor influences as their western neighbours" on the same street.[51]: 53

Six houses and shops, Longsight, Manchester, 1899[edit]

E. H. and A. Bown were calling for contractors for this job from 18 March 1899. It involved "the erection and completion of six dwelling-houses and shops" in Longsight, a suburb of Manchester, and the client was Aerated Mineral Waters Association Limited.[30]

Duchy House, Harrogate, before 1902[edit]

This Harrogate building was originally a residence for G. R. Cartwright, the Surveyor General to the Duchy of Lancaster. It was designed by Arthur Bown, possibly in collaboration with his brother, and on the Duchy Estate, which is still owned by the Duchy of Lancaster.[4][62] The above Queen's Park Lodge and its surrounding park was "enclosed, laid out, planted and ornamented under the immediate superintendence of the Surveyor-general of the Duchy [of Lancaster], Mr Cartwright",[37] so it was for that client that the residence was designed by Bown.[nb 16]

This is possibly Duchy House, 59 Duchy Road, Harrogate, which is on the Duchy of Lancaster Estate and is of the style which was being built in Harrogate in 1902.[63]

Works: restorations, additions and extensions[edit]

Alterations to Trinity Church, Ripon, 1873[edit]

This was a seven-month job for Henry Edwin Bown, involving alterations and improvements to Trinity Church, Ripon. The Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer said:[64]

The old-fashioned pews have given way to low open seats of pitch pine; the west end gallery has been restored to its original dimensions – it having been removed some years back. The pulpit has been remodelled, and the old reading desk replaced by one of pitch pine, varnished, and a neat brass lectern has been provided. New porches have been added at the two west entrances, and the chancel window has been filled with stained glass. The church has been redecorated, and this and the alterations are from designs furnished by Mr H. E. Bown, architect, Harrogate.[64][nb 17]

As of 2022 the pews, pulpit, reading desk and lectern were gone, but the east window was still there. In 1873, before the alterations were quite completed, there was an opening service, with a procession of clergy headed by Robert Bickersteth, Bishop of Ripon. There was an organ voluntary, a service, and a sermon by the bishop, who said that the bill for the works had been £900 (equivalent to £84,840 in 2021) and the church still owed £150 (equivalent to £14,140 in 2021). "The offertory box realised £19 2s 3d" (equivalent to £1,795.78 in 2021).[64][26]

Restoration of the former St Mary's Church, Harrogate, 1874[edit]

After the designs were agreed and drawn up, this job was completed on site within three months. Henry Edwin Bown made his initial call for builders in February 1874.[65]

On 14 May 1874, this church in Westcliffe Grove, Harrogate (built 1822, demolished after 1903)[66] was reopened on Ascension Day after Bown's restoration, at a cost of £600 (equivalent to £59,263 in 2021),[26][67] mostly raised by subscription. "The old low roof and flat ceiling [had] been removed, and a new high-pitched roof, with open timbers, [had] been erected, and other improvements made". The original flat ceiling had been supported by pillars, but now "the walls above the pillars [had] been raised several feet ... This roof [was] lined with pitch pine and supported by open timbers, all stained and varnished to match the open sittings of the church. The chief timbers of the roof [sprang] from carved stone corbels".[67][68]

Additions to Skerry Grange farm house and buildings, nr Sicklinghall, 1891[edit]

This job involved "additions to tenant's house and farm buildings at Skerry Grange Farm, near Sicklinghall, for R.J. Foster Esq.".[69]

Yorkshire Hospital for Chronic and Incurable Diseases, Harrogate, 1895[edit]

The Yorkshire Hospital for Chronic and Incurable Diseases, Harrogate, is as of 2022 converted into flats, and has been renamed as Chapman House, Chapman Square. The same building contained a different environment altogether when in 1895, Arthur Bown designed plans for two additional large rooms, holding ten patients each, to separate those suffering from cancer and tuberculosis from the other patients.[70] The cost of this extension was £250 (equivalent to £30,722 in 2021).[26][71]

Institutions[edit]

Henry Edwin Bown, and possibly his brother Arthur, served on the Harrogate Improvement Commissioners' Board, alongside other local architectural worthies including Isaac Thomas Shutt.[72] Henry Bown was elected ARIBA in 1868.[8] Arthur Bown was a member of the Leeds Architectural Association, the London Architectural Association, and the Arboricultural Association.[20]

Notes[edit]

- ^ GRO: Deaths Mar 1909 Bown Edwin. 86 Knaresbro' 9a 92

- ^ GRO: Deaths Jun 1891 Bown Anne 68 Knaresbro' 9a 105

- ^ GRO: Births Jun 1845 Bown Henry Edwin Halifax XXII 201. Deaths Sep 1881 Bown Henry Edwin 36 Knaresbro' 9a 77.

- ^ GRO: Marriages Dec 1870 Bown Henry Edwin and Husband Sarh Margaret Knaresbro' 9a 189 and 9a 182

- ^ Percy Bown FRIBA was a partner in the Harrogate architectural firm Bland and Bown (dissolved 8 September 1916). He was working at least from 1900 in Harrogate, and extended the Cairn Hotel, Harrogate in 1908.

- ^ GRO: Births Mar 1851 Bown Arthur Knaresboro XXIII 434. Deaths Sep 1916 Bown Arthur 64 Knaresbro 9a 108.

- ^ GRO: Births Dec 1857 Bagshaw Jane Dewsbury 9b 416. Deaths Mar 1917 Bown Jane 59 Knaresbro 9a 155. Marriages Dec 1880 Bagshaw Jane, and Bown Arthur, Dewsbury 9b 985

- ^ This was John Bagshaw of J. Bagshaw & Sons (est.1834), Victoria Foundry, Batley. GRO: Deaths Jun 1897 Bagshaw John 68 Knaresbro' 9a 76.

- ^ GRO: Births Mar 1884 Bown Harold Linley Knaresbro' 9a 106. Deaths Mar 1962 Bown Harold L. 78 Claro 2c 151

- ^ It was customary during the 19th century to complete a full apprenticeship at around 21 years of age.

- ^ The joint partnership would have been instituted when, or after, Arthur was 23 years old, i.e. during or after 1874

- ^ see Harrogate Herald, 12 July 1882, for details of John Henry Hirst

- ^ Historic England has misprinted "Bonn" for "Bown" in its 1001541 listing. There was no architectural practice called "Bonn" in Harrogate at that time.

- ^ The address of the Drill Hall is now Commercial Street, Harrogate

- ^ See File:Memorial to George Kearsley in Ripon Cathedral.jpg

- ^ The identity of the Harrogate residence for G.R. Cartwright, the Surveyor General to the Duchy of Lancaster has not yet been established.

- ^ 19th-century stained glass was very expensive, and a large east window would have cost Trinity Church several thousand pounds in 1873.

References[edit]

- ^ "Deaths". Knaresborough Post. British Newspaper Archive. 25 June 1881. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "1851 England Census HO/107/2282. p.4. 6 Park Parade, Harrogate". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1851. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "West Riding Christmas sessions". Bradford Observer. British Newspaper Archive. 5 January 1854. p. 6 col.3. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p "Arthur Bown". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Architects of Greater Manchester 1800–1940. Retrieved 1 October 2022.

- ^ "Deaths". Leeds Mercury. British Newspaper Archive. 30 March 1909. p. 4 col.2. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ "1871 England Census RG10/4291 p.17. Regent Parade, Harrogate". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1871. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "1861 England Census, 5 Royal Parade, Harrogate (in Pannal parish). RG9/3206, page 14". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1861. Retrieved 17 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e Darlington, Neil (2022). "Henry Edwin Bown". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Architects of Greater Manchester 1800–1940. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "England census 1871. Ref. RG10/4290 p.17, schedule 34". ancestry.co.uk. H. M. Government. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Death of Mr Henry Edwin Bown". Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald. 1 October 1881. p. 5 col.3. Retrieved 28 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1851 England Census HO/107/2322. p.14. schedule 365. Commercial Street, Batley". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1851. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "1900 – houses at Harrogate, Yorkshire". archiseek.com. Archiseek. 4 January 2011. Retrieved 7 October 2022.

- ^ "Deaths". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 18 June 1929. p. 8 col.1. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Marriages". Leeds Mercury. 29 September 1904. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "1881 England Census. RG11/2170.. p.2. Barton Road, Kingskerswell, Devon". ancestry.co.uk. H.M. Government. 1881. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ "Harrogate floral and bird show". Boston Spa News. 14 July 1876. p. 5 col.1. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Deaths". Leamington Spa Courier. 1 October 1881. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 28 October 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Deaths". Yorkshire Gazette. 28 January 1899. p. 7 col.6. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "England census 1871 Ref.RG10/4291 p.17". ancestry.co.uk. Retrieved 28 October 2021.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Scott, W. Herbert (1902). Pike, W.T. (ed.). Central West Riding of Yorkshire at the opening of the 20th century, contemporary biographies (1 ed.). Brighton, UK: W.T. Pike & Co. p. 363.

- ^ "Marriages". Knaresborough Post. 8 January 1881. p. 8 col.5. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Marriage of Miss J. Bagshaw". Dewsbury Reporter. 1 January 1881. p. 7 col.4. Retrieved 2 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "A realistic model railway". Harrogate Herald. 19 March 1947. p. 7 cols 4–6. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "£60,000 cinema for Harrogate". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 22 May 1935. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Deaths". Leeds Mercury. 5 July 1916. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d e f UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 11 June 2022.

- ^ "Latest wills". Sheffield Daily Telegraph. 21 October 1916. p. 10 col.1. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "To builders". Richmond & Ripon Chronicle. 20 June 1874. p. 1 col.2. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b Darlington, Neil (2022). "HE and A Bown". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Architects of Greater Manchester 1800–1940. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ a b "To contractors". Manchester Courier. 18 March 1899. p. 12 col.3. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Arbitration case at Harrogate". Pateley Bridge & Nidderdale Herald. 25 May 1895. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Arbitration case at Harrogate". Knaresborough Post. 25 May 1895. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Dictionary of British Architects, 1834–1914. Vol.1. A-K. London: Continuum. 2001. ISBN 0-8264-5513-1. Retrieved 11 October 2022. (downloadable pdf)

- ^ a b "Progress of Harrogate". Whitby Gazette. 5 March 1870. p. 4 col.4. Retrieved 4 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c "New Congregational manse at Harrogate". Knaresborough Post. 20 August 1870. p. 4 col.4–5. Retrieved 6 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The Rev. Dr Conder". Leeds Mercury. 9 July 1892. p. 17 col.2. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "Heywood and the opening of the Queen's Park. The procession and the opening ceremony". Rochdale Times. 9 August 1879. p. 7 cols 1–3. Retrieved 2 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b c d Historic England. "Queen's Park, Rochdale (1001541)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ a b c Darlington, Neil (2022). "Entrance Lodge, Queen's Park, Heywood". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Architects of Greater Manchester 1800–1940. Retrieved 2 October 2022.

- ^ a b Anon (18 April 1879). "untitled". British Architect: 164.

- ^ "The opening of Queen's Park". heywoodhistory.com. Heywood History. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Dar, Neil (2022). "Fountain: Queen's Park, Heywood". manchestervictorianarchitects.org.uk. Architects of Greater Manchester 1800–1940. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ "To builders". Leeds Mercury. 23 June 1880. p. 1 col.6. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The best penthouse in Yorkshire? Take a look inside £1.5m Harrogate apartment". Harrogate Advertiser. 17 April 2018. Retrieved 4 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Opening of new bank buildings". York Herald. 21 December 1885. p. 3 col.2. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Neesam, Malcolm (2005). Harrogate (Pocket Images). The History Press Ltd. ISBN 978-1845881498.

- ^ "To contractors and builders". Leeds Mercury. 8 March 1884. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "36 Victoria Avenue". The Harrogate Club. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ Chalmers, Graham (7 March 2019). "Harrogate's 'secret' Victorian club is revived". Harrogate Advertiser. Retrieved 23 September 2022.

- ^ "Restoring Harrogate's mysterious The Club that Sherlock Holmes creator loved". Yorkshire Post. 31 March 2016. Retrieved 11 August 2021.

- ^ a b c Neesam, Malcolm (2018). Harrogate in 50 Buildings. Amberley Publishing. ISBN 978-1445681115.

- ^ Historic England. "Jubilee memorial (1315844)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 March 2021.

- ^ "Unveiling the statue of Queen Victoria at Harrogate". Leeds Mercury. 7 October 1887. p. 3 col.4. Retrieved 14 July 2021 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ a b "The Mayor's Jubilee Memorial. Laying the foundation stone". Knaresborough Post. 16 April 1887. p. 4 col.5. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "The dedication of the Mayor's memorial statue". Knaresborough Post. 25 June 1887. p. 5 cols 2–7. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Workmen's supper at the Prospect Hotel". Harrogate Advertiser and Weekly List of the Visitors. 23 November 1889. p. 5 col.2. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "New drill hall for Harrogate. Laying the foundation stone". Knaresborough Post. 26 May 1894. p. 6 cols 1–4. Retrieved 6 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Harrogate – West Riding". drillhalls.org. The Drill Hall Project. Retrieved 6 October 2022.

- ^ "To contractors, tenders". Leeds Mercury. 21 November 1896. p. 2 col.2. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "To builders". Manchester Courier. 18 July 1896. p. 1 col.6. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Salvation Army Barracks. Laying of memorial stones". Knaresborough Post. 30 January 1897. p. 6 cols 4–5. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Grainger, John (12 August 2021). "The Duchy Estate – Harrogate's leafy suburb of 'forever homes'". Harrogate Advertiser. Retrieved 3 October 2022.

- ^ "50 Duchy Road, Harrogate, England". instantstreetview.com. Street View. May 2022. Retrieved 12 October 2022.

- ^ a b c "Ecclesiastical news. Reopening of Trinity Church, Ripon". Yorkshire Post and Leeds Intelligencer. 28 November 1873. p. 3 col.7. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "To builders". Leeds Mercury. 14 February 1874. p. 12 col.5. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ Chalmers, Graham (28 August 2020). "Where now for Harrogate's much-loved St Mary's Church after decades of decline and deterioration". Harrogate Advertiser. Retrieved 5 October 2022.

- ^ a b "Restoration and re-opening of St Mary's Church". Knaresborough Post. 16 May 1874. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 5 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Building intelligence: churches and chapels: Harrogate". Building News. 22 May 1874. p. 31/571 cols 2–3. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "To builders". Boston Spa News. 24 July 1891. p. 4 col.1. Retrieved 8 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Yorkshire Hospital for Incurables". Leeds Mercury. 27 October 1885. p. 5 col.4. Retrieved 6 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Yorkshire Home for Chronic Diseases". Knaresborough Post. 31 October 1885. p. 8 col.1. Retrieved 7 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

- ^ "Harrogate Improvement Commissioners". Knaresborough Post. 8 July 1871. p. 4 col.6. Retrieved 3 October 2022 – via British Newspaper Archive.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to H. E. and A. Bown at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to H. E. and A. Bown at Wikimedia Commons