First French War of Religion in the provinces

Across France Protestants responded to Condé's manifesto and the beginning of the first French War of Religion by seizing cities and taking control of territories. In total around 20 of the 60 largest cities in the kingdom would fall under rebel Protestant control. Among them Lyon, Tours, Amboise, Poitiers, Caen, Bayeux, Dieppe, Blois, Valence, Rouen, Angers, Le Havre, Grenoble, Auxerre, Beaugency, Montpellier, Mâcon and Le Mans. In the areas of Protestant domination iconoclasm and the seizure of churches was often undertaken. Protestant armies attempted to seize more cities that had not fallen to them. Among the leading Protestant commanders were the comte de Crussol (count of Crussol) who assumed a position of leadership in Languedoc and Dauphiné; the baron des Adrets in Dauphiné, the seigneur de Duras (lord of Duras) in Guyenne; the prince de Porcien in Champagne and the comte de Montgommery in Normandie.

This decentralised uprising would not be unopposed, and after initially being caught off guard by the sudden and dramatic nature of the conquests, local Catholic royalist commanders would begin to recapture the territories in their provinces. This included figures such as the seigneur de Monluc in Guyenne and Languedoc, the vicomte de Joyeuse (viscount of Joyeuse) in Languedoc; the comte de Sommerive in Provence; the duc d'Aumale in Normandie and the duc d'Ėtampes in Normandie. This would involve street battles to stop attempted Protestant seizures of cities (as in Toulouse and Bordeaux), the reduction of Protestant held cities (as with Poitiers and Rouen) and field battles (as in the defeat of the Protestant army of Duras by Monluc's army at Vergt in October.

By the end of 1562 the rebel Protestant presence in much of France had been successfully neutralised. However, in Languedoc and Dauphiné they remained entrenched under Crussol's leadeship. Meanwhile Admiral Coligny oversaw the resurgence of their cause in Normandie shortly before the end of the war.

Picardie[edit]

The court moved to assure itself of its control over Picardie and its capital Amiens with the provinces governor in rebellion. Under the legal fiction that Condé was a prisoner of the rebels in Orléans, his brother the cardinal de Bourbon was made governor of Picardie in his stead. Bourbon entered Amiens on 27 July.[1]

Amiens[edit]

The Protestants had enjoyed great success in assuming influence in Amiens, and by 1562, seventeen of the twenty-four échevins (aldermen) were Protestant.[2] During the ascension day procession, the échevins ensured it would be four of their number who carried the important châsse de Saint-Firmin (shrine of Saint-Firmin). A Protestant served as one of the cities schoolmasters. The remaining Catholic échevins were not willing to allow the Protestant success in the city to continue, and both the mayor and the prévôt (provost) were accused by them of being partisans of the Protestants as far as overseeing the prosecutions of the disorders of 7 and 8 December were concerned. It was further implied by the Catholics that they intended to launch a Protestant coup.[3]

The Protestants of Amiens looked to the Protestant lieutenant-general of Picardie, the sieur de Sénarpont and Condé to defend their interests at court. Condé assures them of his protection and for the moment this proved more decisive than the coalition around the bishop of Amiens (which included the bishop of Nantes and Montmorency). Another appeal to the court by the radical Catholic faction was launched on 23 April with the dean of the local chapter travelling to court to get the keys removed from those who currently possess them as 'most of them were Protestants'. Those who travelled to the court highlighted the recent Protestant seizure of Rouen. The court was more sympathetic this time, Condé no longer present to represent the Protestant interests. On 5 May, the mayor and prévôt were replaced by the court, with the latter departing to join Condé in rebellion at Orléans. Within another month, Catherine appointed ten new échevins, all Catholic, giving the Catholics a municipal majority. This new Catholic majority quickly moves to neutralise their Protestant colleagues.[4] The cardinal de Saint-Tryphon visited the city on 22 May to announce that it was the king's will that Protestant worship be proscribed in Amiens and other border cities. The Catholic échevins happily announced the expulsion of Protestant ministers in response. During July the abjuration of all Protestants in Amiens was decreed, with some who refuse to abjure choosing instead to leave the city.[5] In the municipal elections of October a last minute addition to the electoral rules made Protestants ineligible from participating.[6]

Montdidier[edit]

The royalist recapture of Montdidier was undertaken by deception. Having promised that the Protestants of the city would be safeguarded, the royalist force butchered and expelled them.[7]

Calais[edit]

In May, the lieutenant-general of Picardie the sieur de Sénarpont made an abortive attempt to capture Calais.[8]

Champagne[edit]

Troyes[edit]

Condé reached out to his nephew (who happened to also be in the capital when word of Wassy arrived), the Protestant - or at least Protestant sympathetic - governor of Champagne duc de Nevers to source military and financial aid for the cause.[9][10] Nevers had received the charge of governor of Champagne from his father in 1561, the latter having resigned it to him.[11] Nevers passed the request he received on to the Protestant church of Troyes which was already in the process of arming its members.[12][13][14]

In Troyes, close to Wassy, tensions were escalating severely between Protestants and Catholics with both accusing each other of interfering with the electoral process in the city.[12] On 6 April, a representative of the duc de Guise, Esclavolles, passed through Troyes. He decided to preside over the election of the échevins which had been delayed, and excluded Protestants from the process. He further took charge in Troyes and demanded the keys. On 10 April he declared only Catholics would guard the gates.[15] The Protestants dispatched a representative to Nevers to warn him that his authority was being usurped.[16] On 12 April, Protestants seized two of the city gates, assaulting the gate keepers. Though there was bloodshed, it was comparatively bloodless in comparison with cities such as Toulouse.[17] A captain on the way to join Condé passed through Troyes, and reported back from Orléans to the Protestants that Condé desired them to obey Nevers. Nevers arrived near Troyes on 19 April, with the intention of calming religious tensions in the city. He was aware that the Protestant community of Troyes had armed and wished to keep the situation under control. He wrote to the court that agitators from outside the town were attempting to escalate the situation.[18] He was eventually able to persuade the Protestants of Troyes to stand down by promising to protect them.[19] Nevers, now corresponding with the crown, adopted a posture of neutrality. Both religions were to guard the gates, and weapons were to be yielded to him.[20] He hoped this would dispel fears of a new massacre of Wassy.[21] However many Protestants refused to hand over their weapons and instead hid them.[22] Protestant troops that had been raised initially at Nevers' request, slipped out of the city to join with Condé on 5 May.[23] Nevers moved to have those who did not live in Troyes expelled from the city.[18] Nevers was frustrated with the Protestant congregation of Troyes for their having sent troops to join with the Protestant rebels. He preferred the company of the Protestant bishop of Troyes Antonio Carraciolo to his co-religionists in the city.[24]

In July, the Protestant prince de Porcien was in the area, and threatened an attack against Troyes, though it did not materialise. Fearful of a plague, Nevers retired from Troyes, leaving his more firmly Catholic subordinate des Bordes in charge.[25][26] Nevers turned his attention to the nearby settlement of Châlons, where he had heard rumours of religious disorder. He was assured by the city council that while a Protestant preacher had been causing problems, the situation was now under control.[27] In August repression against the local Protestant population began in Troyes.[28]

On 24 August, des Bordes led an assault against the Protestant held town of Bar-sur-Seine. The Protestant cavalry guarding the town fled, and des Bordes oversaw a massacre of 140 Protestant inhabitants.[29] Nevers' gendarme company participated in the killings, and according to Carroll the attack could not have happened without his approval. For Nevers, this was a military action against rebels, and therefore justified.[23] According to the local contemporary historian Nicolas Pithou they tore out the heart of one of the Protestants and then took turns biting it.[30] Those who survived were brought back to Troyes for trial, and then executed.[31]

Bar-sur-Seine once more fell to Protestant forces in January 1563, this prompted a new round of persecutions and killing in Troyes.[31]

Sens[edit]

When the Protestants of Sens initially began pushing to receive churches, the mayor refused on the ground that the edict of Saint-Germain had not been registered. After it was registered he altered course to insisting the preachers of Sens speak out against the edict. On 29 March while returning to Courtenay from Sens where they had held a service a group of Protestants were attacked by Catholic boatmen. Local Protestant gentleman quickly intervened to protect them, but services were nevertheless suspended for the time being.[32]

Before taking action, the Protestants looked to Nevers for leadership, but none came. While they stalled, the royalist Catholics of the city took the initiative. A militia was established (financed by the clergy), the gates secured and the artillery seized. A meeting was held among the Catholic grandees of Sens to decide how to proceed.[33] It was decided to raze the Protestant church in Sens, on the day of the pilgrimage for St Savinien, when their numbers would be able to overpower the Protestants strong representation among the magistracy of the city. On the day the Catholic militia stood guard as the people of Sens tore down the church.[34] Arrests of the Protestant leadership then began, and though chaotic did not descend into bloodshed in the morning. In the afternoon the Protestant captain returned and began preparing for a counter offensive, uniting with a band of co-religionists in a fortified house and then bursting out to attempt to push the Catholics back out of the neighbourhood. The captain attempted to make contact with a gendarmerie company of Coligny's. The Catholics brought up artillery and the captain was killed, with his unit dispersed. The general massacre then began. Canons invited peasants from the surrounding countryside into Sens to participate in the killing.[35] According to the Protestants, 52 houses were pillaged and around 100 killed. Not all the killed were Protestants, with one Catholic magistrate being killed as he left mass.[36] The parlement would investigate the incident but did not find anyone guilty.[37]

Reims[edit]

In Reims, there was relatively little risk of any Protestant uprising, the city would not be subject to any external attack or internal disorder during the war. Nevertheless, the baron de Cerny was appointed governor of the city in July. He ordered the council draw up a list of Protestants in the city, which was happily complied with by the city council.[38] They provided Cerny a list of 25 names in September.[39] No action was taken with the information on this list, as it was apparent the named were either not actually Protestants or presented no military threat to the city.[38]

The duc de Nevers led an assault on a Protestant held château near Reims. He and his 1,600 soldiers tricked the garrison into emerging from the château and then slaughtered them.[23]

Porcien's campaign[edit]

The prince de Porcien spent the spring pillaging the countryside of Champagne. He operated primarily from a base at Montcornet in northern Champagne. He initially made his way to join with Condé in Orléans, attempting to surprise Provins on route with the support of the towns Protestant bailli (baillif). After a couple of months with Condé he returned to Champagne via Strasbourg.[40] In Strasbourg he recruited 100 cavalrymen.[41] In July he was back in Champagne, operating around Joinville with the support of the seigneur d'Esternay who had been dispatched to the province by Condé.[42] In response to the military threat his presence in the province posed, the town of Châlons introduced a garrison of around 300 soldiers for its defence against him.[43] This was not satisfactory for the governor, the sieur de Bussy who tried to push another three companies on Châlons on the grounds that many Protestants were in the area, and could surprise Châlons at any moment. The city council rebuffed this offer, content in the services of their royal captain the sieur de Castel for their security.[39] They argued more troops would worsen the plague, and moreover the number they had was sufficient. Bussy began selling off the property of Protestants that had fled from Châlons in August. While the council acquiesced to this, it refused Bussy's request for a list of all the Protestants resident in Châlons.[44] During Autumn, Porcien returned, and his force began pillaging the area between the Meuse and Marne.[45]

On 25 August, Porcien began a siege of Sainte-Menehould, which was governed by the sieur de Bussy. He brought to bear 4,000 foot soldiers and a further 800 cavalry. Bussy had entrusted the defence of Sainte-Menehould to a captain Lescouardin, who was able to repulse Porcien's attack. During the combat Porcien was wounded, and lifted the siege, his forces returning to plundering the surrounding countryside. The abbeys of Châtrices, Moirement, Moutier and Beaulieu were sacked by his men. During September his force successfully captured the château and priory of Sermaize.[40]

Normandie[edit]

Iconoclastic action and church seizures would occur in many Norman towns and cities including: Rouen, Dieppe, Caen, Caudebec, Jumièges, Saint-Martin-de-Boscherville, Bayeux, Elbeuf, Barentin, Limesy, Coutances, Avranches, Sées, Saint-Lô, Saint-Wandrille and Le Tréport. Now led by the more 'respectable' elements of Protestant society the iconoclasm was more systematic with inventories drawn up and auctions organised. The funds were to be used to fund the movement in the province.[46]

During May Saint-Lô, Bayeux, Falaise, Vire, Lisieux, Carentan, Pont de l'Arche and Le Havre fell to Protestant rebel control.[47]

Bouillon's party[edit]

The Protestant governor of Normandie did not affiliate with the rebel Protestants, or the crown and instead established a third party the purpose of which revolved around reinforcing his own authority in the province.[47]

Governor Bouillon was furious that the duc d'Aumale and the seigneur de Matignon had been provided with powers of lieutenant-generalcy in Normandie on 14 May to restore order in the province.[48] Matignon was a client of the queens, and she hoped he would serve as a counterweight to Aumale.[49] Even though Aumale was his uncle-in-law, Bouillon saw these commissions as attacks on his authority. He therefore established a headquarters in the château de Caen and with the support of local Protestants besieged Matignon in Cherbourg.[47][50] Matignon undertook to increase the defences of Cherbourg while he awaited reinforcements.[49]

Protestants and Catholics were able to exist together peaceably under Bouillon's auspices.[51] Indeed, on 19 March 1563, Bouillon would introduce a policy of religious coexistence inside Sedan, a territory over which he was prince.[52]

Bouillon corresponded with the court, complaining that the money he was owed for the campaigns he was conducting went unpaid. With the intervention of Guise and the duc de Montpensier at court in his favour the commissions of his captain Berteville were recognised and he was granted commission over three companies while Bouillon was allowed to utilise the treasury of Caen.[53]

Late in 1562, he tried to put his captains in place, and gain acceptance for the return of Protestant refugees to the towns of Saint-Lô and Bayeux both of which were under Catholic control. They refused, and Bouillon declared the towns to be enemies of the king, lodging an appeal with the court.[54]

Caen[edit]

On 28 April, the duc de Bouillon wrote to the officers of the baillage of Caen. He thanked them for the diligence they had shown in the maintenance of the city to this point. He informed them the crown had granted full powers to the captain d'Hugueville to act as governor. Soon thereafter, d'Hugueville ordered the stockpiling of foodstuff in the château. Dauvin thus speculates that d'Hugueville anticipated an attack.[55]

According to a Catholic eyewitness the minister announced his intention to see the town rid of 'idols' in front of the judiciary of the city.[56] With d'Hugueville seemingly preparing for an attack, a great wave of iconoclasm broke out on the evening of 8 May and continued through 9 May.[57] This came shortly after the destruction of images in Rouen on 3–4 May.[58] According to the later account of Bourgueville all the churches and monasteries were attacked with their images destroyed, windows shattered, ornaments pillaged and flammable elements all thrown into fires. One of the first targets for destruction was a fifteen feet tall cross under the window of one of the présidial judges. The city militia despite being close to much of the action maintained a complicit neutrality.[59] Bourgueville would estimate the damage of the two days to be at the value of 100,000 écus. According to the historian it was only the arrival of Matignon which prevented an assault on the château from following the destruction of the churches.[57]

The présidial court was divided between Protestants of a legalist persuasion who disapproved of iconoclasm, and those of a more revolutionary persuasion who approved of the acts.[58] Bourgueville states (as an eyewitness) that when the iconoclasts presented themselves before the body after conducting their deeds, one of the Protestant justices absolved them of any criminal liability.[57] The iconoclasts were paid for the work they had undertaken.[56] By the violence of these days Catholic worship was de facto suspended. However the Protestants of Caen remained divided on whether to seize the opportunity and impose Protestantism on the city.[59] While control would be assumed over many churches, the civic bodies of the city would continue to function as before, and the Protestants had failed to secure the château.[60]

Catherine entrusted the duc de Bouillon with overseeing the preservation of Caen for the royalist cause. Bouillon arrived in front of the château on 20 May with two companies of soldiers.[61] Bouillon made d'Hugueville depart his charge and then the city, alleging that the captain wished to establish Aumale over Caen.[61] Locking himself up in the château, Bouillon had the nearby collegiate church destroyed with cannons on the grounds that its elevated position near the château was a security risk. He ordered the systematic looting of the remaining silverware from the churches of Caen to finance several companies of light horse under the Protestant commanders the sieur de Fervaques and Jean de Pellevé both of whom had been or would be responsible for the destruction of Catholic religious property.[62][63] [64]

On 4 September, Bouillon oversaw the ousting of the majority of the recently elected échevins replacing them with his own Protestant appointees. In doing this he took advantage with royal frustration with the municipal authorities of Caen.[65]

In September the Protestant commander Montgommery was operating around Caen with around 3,000 footsoldiers and 800 horsemen.[66] With the duc de Bouillon absent, he attempted to seize the city but the attempt was foiled with the conspirators inside Caen hanged.[63]

Bouillon sponsored a delegation from Caen that plead with the court for liberty of conscience. The court responded on 21 October with an order that all Protestant preachers in Caen must depart on pain of death, with public Protestant worship prohibited. The governor of Normandie was able to broker a compromise by which public worship would cease but liberty of conscience and private practice of Protestantism would be permitted. This was published on 3 November.[54] Nevertheless, Protestant ministers would have to depart from Caen.[67] On 29 November the crown established a new captain of the château and city, the sieur de Renouard, a client of Jean III d'Annebault. While some of the Protestants of the city sought to make a good impression on their new commander, others felt with the loss of Bouillon a new protector was required.[68]

Renouard undertook the disarmament of the population of Caen and saw to the transfer of all municipal arsenals contents to the château. By these means the Protestants of the city feared they would soon be subject to a similar repression as their co-religionists in Rouen.[69]

On 14 February Coligny entered Caen. According to de Bèze the Protestant occupation came as a response to governor Renouard attempting to undertake a massacre of the cities Protestant population before being stopped and pushed back by some exiles from Rouen. Meanwhile, according to the local historian Bourgueville, the Protestants took advantage of the poor authority enjoyed by the governor to see the gates opened for Coligny.[69] Dauvin, highlighting an incident with the bell a couple of days prior finds the latter account more credible.[70] Coligny's entry without need for a prolonged siege was a great scandal.[71] With the city secured Coligny turned to the château where Renouard was held up and put it to siege. He was aided in his efforts by 2,000 English soldiers under Throckmonton. On 2 March Elbeuf surrendered the château to him. From 5 March de Bèze preached for ten days in Caen.[70] Coligny departed Caen on 16 March after ordering the removal of the lead roofing of the abbey church, which would be melted down and sold for 80,000 livres. Montgommery was established as the cities new governor.[72]

Dieppe[edit]

No sooner did word arrive of what had transpired at Wassy than Dieppe entered into a state of disorder with the Protestants assuming control of the city on 22 March.[47] In the violence that followed 150 Protestants and Catholics would be killed.[73] The Protestant captain of Dieppe, Ponsard was a client of Coligny's.[48]

The governor of Normandie, the duc de Bouillon visited Dieppe in April. He was granted a ceremonial entry into the city, but was informed his choice of governor for the city (a Catholic) was unacceptable. His failure to restore either Dieppe or Rouen to obedience with the crown led to his replacement as military leader of Normandie by the duc d'Aumale.[74]

The Protestants of Dieppe, now in control came to the aid of nearby co-religionists who were more vulnerable. Cany, Veules and Saint-Valéry-en-Caux were thus attacked from Dieppe when news reached the city that there were 2,000 Catholic peasants in the area.[75]

The commander of Dieppe, the seigneur de Briquemault was appointed as commander of Rouen in September. However, Briquemault would remain in Dieppe, writing appeals to Elizabeth for support without result. With the city subject to a siege he agreed to its surrender on 30 October.[76] The English garrison was expelled on condition that private Protestant worship be respected. This surrender came in part from fear at seeing the brutal sack which Rouen had recently been subjected to.[77] The Protestant governor who had replaced Bricquemalt, the sieur de La Curé was chased out of the city after the surrender.[78]

In early 1563 Dieppe was again besiged. This time the comte de Brissac in command of a royalist force led the effort. Command of the defence was in the hands of the comte de Montgommery.[79]

Rouen[edit]

In Rouen, word of the massacre of Wassy inspired panic and preparation from the cities Protestant population. This was then combined with word of Condé's manifesto. Therefore, when two Norman royal recruiters visited the city to raise soldiers, they were attacked, accused of plotting a new Wassy. One of them received injuries while the other was killed.[80] The bailli of Rouen, Villebon visited the city a few days later. Villebon was an ultra-Catholic who over the prior years had developed an infamous reputation with the cities Protestants.[81] Protestants accused him (either genuinely or disingenuously) of plotting to seize the weapons in the hôtel de ville (city hall) and therefore on 15 April the Protestants seized first the convent of the Celestines, and then the hôtel de ville. The beleaguered Villebon was besieged in the cities château.[82] He quickly surrendered and fled, leaving the Protestants the masters of Rouen on 17 April, his lieutenant who was held up in the Vieux Palais having likewise surrendered.[83] Control of Rouen (and Le Havre) allowed the Protestants to dominate the lower Seine.[84] On 19 April the duc de Bouillon arrived in the city.[83] The new leaders of the city stressed their continued loyalty to the king, arguing that they had only acted to prevent a new Wassy. Frustrated that the city would not in fact actually return to obedience, Bouillon departed, leaving his lieutenant the sieur de Martel in the city. In the city Catholic Mass was allowed to continue, and the Catholic members of the city council were left in place. This could not contain the more radical in the city, and Protestants went from church to church smashing Catholic paraphernalia and pulling it from the churches to burn in large bonfires.[85] Catholic homes were invaded and arms seized. Therefore, by the end of May, most Catholics had departed Rouen. On 14 May, in the wake of the Protestant iconoclasm, Bouillon's lieutenant Martel withdrew from Rouen.[48] The Parlement left into exile, and the Council of Twenty Four became solely Protestant in June.[86] The Protestants of the city began a systematic weighing and melting down of precious metals in the city, and by this means raised around 57,000 livres which was put towards paying the garrison and preparing the cities fortifications.[87]

Catherine negotiated with the city during this time, offering leniency in return for re-admission of royal officials into Rouen. The Rouennais leaders demanded that the recent commission granted to the duc d'Aumale to raise troops across the region be revoked. Catherine could not consent to this. On 28 May, Aumale arrived before Rouen and demanded the gates be opened to him, the city refused. He began a weak siege, lacking enough in the way of force (possessing only around 3,000 men) to truly threaten the city. He contented himself to harass the city. Meanwhile, he issued commissions to sympathetic nobles such as Villebon, and the clients of Brissac.[49] Protestant soldiers from around Rouen flocked to the cities defence. The combined Rouennais and external Protestant forces launched raids on nearby towns, such as Darnétal, Elbeuf and Caudebec.[88] The Protestant commander in charge of Rouen at this time was the seigneur de Morvilliers who oversaw the receipt of reinforcements to resist Aumale from Orléans.[89] Morvilliers could count on around 4,000 men in the city during June.[90]

The exiled parlement, established at Louviers radicalised quickly, devoid of its chief moderates the minority ultra faction took charge.[91] The parlement issued an arrêt in which they declared that Protestant worship would be prohibited in the regions of Normandie under royalist control.[92] The parlements penchant for hanging random Protestants forced the court to despatch Michel de Castelnau in August to restrain their extreme impulses.[91]

Aumale returned for a second attempt at besieging Rouen on 29 June, installing batteries in front of forte Sainte-Catherine. He would however achieve little more success at reducing the city than he had in his prior siege. He contented himself with giving licence to the nearby peasantry to attack the Protestant nobility.[93] He financed himself through plunder, requisitioning the cloth of the Rouennais merchants that was at Brionne.[94] In September Morvilliers found himself in conflict with his co-religionist Montgommery over the latters desire to supplement the cities defence with English forces and withdrew from the city.[90] To replace Morvilliers the seigneur de Bricquemault was chosen, however he could not reach Rouen.[76]

Honfleur[edit]

On 21 July, Honfleur was seized by the duc d'Aumale.[7]

Bayeux[edit]

The bishop of Bayeux was captured by Protestants, but the Catholic townspeople were able to successfully see to his release.[95]

Le Havre[edit]

On 16 April, Le Havre was seized by the Protestant commander Maligny, who had been involved in the conspiracy of Amboise. In assuming control he expelled from command the Catholic lieutenant Jean de Cros.[55] This came as a blow to the royalist cause as it facilitated contact with England.[73] His seizure of Le Havre was of considerable concern to the government, as it was the primary port of supply.[50] As a term of the treaty of Hampton Court, Le Havre was to be handed over to the English. An English force departed Portsmouth on 1 October and received Le Havre on 4 October.[96]

The English commander of Le Havre, the earl of Warwick was besieged by Marshal de Vielleville during December. Vielleville based himself out of Caudebec for the purpose of the siege.[97] During January around 7,000 German mercenaries were involved in the siege, and they terrorised the countryside around Le Havre.[98]

Vire[edit]

In August there would be Catholic riots in Vire, with the duc de Bouillon re-establishing order.[53]

Caudebec[edit]

The day after the capture of Le Havre, the Protestants secured Caudebec by means of an uprising. Troops loyal to the Protestant cause had been secreted into the city in prior days, which enabled Caudebec to resist an attempted siege by a local royalist force.[73]

Lisieux[edit]

On 5 May the Protestant bailli of Évreux and the captain of Tancarville, a client of Longueville's, jointly pillaged the cathedral town of Lisieux.[48]

When the duc de Bouillon arrived at Lisieux he ensured the resumption of Catholic worship in the town. He would however provide a Protestant governor to counterbalance this restoration.[63]

Tancarville[edit]

The Protestant prince Longueville's château at Tancarville became a haven for Protestant fleeing from Catholic attacks. In October Longueville wrote to the captain of Tancarville instructing him to surrender the château to the royalists.[99]

Valognes[edit]

Peace was initially maintained between Catholics and Protestants in Valognes. A bi-confessional assembly of notables agreed to resist calls to arm and expel populations and instead abide by the king's edicts together in peace. A bi-confessional militia was able to keep the peace when there was an incident around Pentecost. However, on 7 June Catholic militia-men fired on a group of Protestant notables. Most of the Protestants were able to escape thanks to the protection of their Catholic neighbours. The killing would not go unavenged, and a local Protestant force entered the town and killed a Franciscan monk.[100]

Bouillon for his part despatched a military provost to Valognes to punish the perpetrators. The Catholics of Valognes threw the provost into prison and declared that their loyalty was not to Bouillon but rather to the lieutenant-general Matignon in Cherbourg. Bouillon therefore attacked and conquered Valognes with 2,200 men and had some of the rioters hanged, before making preparations to attack Cherbourg.[63]

Lyonnais[edit]

Lyon[edit]

It was not possible to establish the Edict of Saint-Germain in the kingdom's second city as it was increasingly consumed by more extreme factions of Protestants (who wanted total freedom of worship) and Catholics determined to resist the edicts application.[101]

The governor the comte de Sault, who though not Protestant himself, was sympathetic to Protestantism, was suspected of involvement in the Protestant coup that seized the city on the night of 29 April.[102] He had been appointed to the charge in 1561.[103] In the proceeding months, the administration of Lyon had paid La Motte-Gondrin to quarter his troops outside the city proper (leaving him in the faubourg de Vaise) and turned down a request by Saint-André to construct a fortified gate on the Saône bridge, by which means the more Protestant parts of the city could have been isolated.[101]

Only the canons of Saint-Jean and the governor put up resistance to the Protestant coup that acquired the city.[104] The church of Saint-Nizier and the hôtel de ville were seized, the former protected with guards. The towers that guarded the squares were likewise conquered.[105] The cathedral of Lyon was subject to a sacking, with a Protestant pastor invading the cathedral sword in hand to this end.[106] Thus the Protestants acquired what they had failed to seize in September 1560.[107] One of the Protestant ministers of Lyon, Jacques Ruffy was particularly involved in the violent seizure of the city who even bore arms. This action was reported to Genève, and earned Ruffy a rebuke from Calvin, with Calvin going on to chide the ministers of the city generally for their role in the coup.[108] Calvin highlighted that he had been informed Ruffy had confronted the governor of Lyon with a pistol and boasted of the Protestant forces in the city.[109] Soon after the Protestant conquest, the baron des Adrets arrived, he had not been given a commission to govern Lyon (his authority limited to Dauphiné), but he assumed it unilaterally. There was little protest to his acquisition, as it was assumed he would soon depart back to Dauphiné.[105]

The new Protestant administration of Lyon prohibited the participation of Catholics in the cities consulate. Many of the bankers of the city were Catholic and departed, however some affiliated themselves with the Protestant administration.[110] Lyon was governed by the brutal Protestant commander the baron des Adrets from May to July. He had the former clerical property of the city carefully inventoried while other items were destroyed. His brutal command was so displeasing to Condé and Coligny that he was replaced in the city by the sieur de Soubise in July.[111] Soubise wrote to Catherine explaining that he remained totally loyal to the king and that as soon as Charles and Catherine were at liberty he would restore Lyon to their control and obey all their commands.[112] In September, orders were issued in the 'name of the king' by which blasphemy and gaming were outlawed, with attendance of Protestant services made mandatory. Commerce was to be prohibited during hours of worship.[113]

The city held out against attempts by the royalist duc de Nemours to reduce it. The Protestants would hold Lyon until 1563 when it was returned to the royalist fold through negotiation as opposed to military force.[114][115]

After the disgrace of Adrets from the Protestant cause, the seigneur de Montbrun would assume the military role he had held over the Lyonnais, Dauphiné and Vivarais.[116]

Maine[edit]

The royalist Catholic sieur de Champagne et de Parcé was responsible for the conduct of various atrocities in Maine.[117] He had suspected Protestants thrown into a deep lake, and was reported to have remarked as he did that he would make them 'drink from his big bowl'.[118][119]

Le Mans[edit]

In Le Mans, the Protestants forced their bishop Charles d'Angennes to flee from the city around the time of the Massacre of Wassy. A meeting was conducted to plan for the seizure of the city on 1 April at the hôtel de Vignolles under the leadership of the seigneur de la Rochère featuring various grandees of the city.[120] Control of Le Mans itself was secured by the rebels on 3 April. The Protestant seizure was accompanied by a wave of pillage against the churches and convents of the city. Treasures were removed from the cathedral, manuscripts were set ablaze. The cardinal de Luxembourg was disinterred from his resting place.[121] The primary offenders in this destruction were the bourgeois and 'notables' segments of the Protestant population.[122][123] With the Catholic population fleeing, the city remained in the hands of Protestant soldiers for three months.[124] The cities Protestant military leader was La Motte Thibergeau and he was supported by the future comte de La Suze (a cousin of the sieur de Champagne's).[120][119] On 29 April, the Protestants of Le Mans' remonstrated the king, echoing the manifesto that Condé had issued, they plead with the king to hear their arguments about the cruelty of Guise, the 'architect of Wassy'. On 11 July, the bishop returned at the head of a military company and re-secured the city for the royalists.[125][126] Back in power, the bishop went house to house across the nobility of Le Mans securing participation in a Catholic League he had founded.[127] La Motte Thibergeau led an exodus of Protestants into Normandie.[120]

Anjou[edit]

The governor of Anjou, Touraine and Maine, the duc de Montpensier, found himself short on artillery for the conduct of his local campaign. He therefore made request of the governor of Bretagne, Étampes, who informed him that no captain in his province would provide such resources to him without his explicit authorisation. After Étampes wrote to the local commanders, Montpensier would receive Breton powder.[128]

Angers[edit]

In Angers, Montpensier oversaw brutalities against Protestants. At his instruction the Protestants were variously hanged, beheaded and beaten.[129]

The city was conquered for the rebel Protestant cause by an alliance of the urban and rural nobility.[130] La Rochefoucauld was operating around Angers in May, keen to revenge himself for Montpensier's cruelties.[8]

Touraine[edit]

Tours[edit]

Montpensier, governor of Touraine, oversaw the execution of a butcher of Tours who was found to be selling meat during Lent. Following this some Protestants were imprisoned in the residence of the archbishop.[131] Montpensier then retired to his estates at Champigny, leaving the field open to the Protestants.[132]

On 30 March, prior even to Condé's capture of Orléans, a group of several hundred Protestants captured the château de Tours with little resistance.[132] A few days later the rest of the city fell to them.[133] Representatives from Condé in Orléans soon arrived. With the city in their hands the cathedral of Tours was subject to iconoclastic violence alongside the abbey of Saint-Martin where the shrine was broken on 5 April. Precious metals were melted down and sent off to pay Condé's emerging army in Orléans.[132] Saints remains were also burned, as was the fate of saint François de Paule who was kept in Plessis-lès-Tours.[134]

In July Saint-André put Tours to siege. The Protestants negotiated their safe withdrawal and surrendered the city. Saint-André proved either unable or unwilling to honour this agreement. Hundreds were massacred and thrown into the river Loire. The Protestant mayor was dismissed and all Protestants still alive in the city were to swear a confession of faith to Catholic judges or depart the city. When Montpensier arrived in the city he ordered a list of all the Protestants in the administration be drawn up so that they might be purged.[132]

Montpensier did not find governing easy in this period. In December 1562, he wrote to the court protesting that all his requests for royal favours for his clients went unanswered, leaving him unable to command respect or maintain his fidelity network properly. It was only through his personal funds that Montpensier was able to reward those who served him, he protested.[135]

Chinon and Loudon[edit]

Guise oversaw the recapture of Chinon and Loudon for the royalist cause.[7]

Bourgogne[edit]

After the departure of the governor Aumale to Normandie, the duc de Guise was established as governor in his absence.[136]

Dijon[edit]

A Protestant plan to seize Dijon by internal coup was foiled.[137] The mayor and city council of Dijon wrote to Aumale, pleading with him to greenlight the arrest of all Protestants who violated the Edict of Saint-Germain. This was despite the fact the council had little intention to register the edict or enforce its terms of toleration. Among many grievances voiced by the council to their governor the centrepiece was the Protestant attacks on the Eucharist.[138] In total they made twelve complaints to Aumale which covered the range of social life from the election of the previous year to observance of feast days.[139] Tavannes, the lieutenant-general of the province, began acting without waiting for word from Aumale. On 8 May he ordered all Protestant preachers in Dijon present themselves before the hôtel de ville the next morning, so that they could receive safe conduct out of Dijon. Any who did not leave would be liable to be hanged without judicial process. Tavannes was encouraged in his efforts by Catherine, who wrote to him in June that he should continue his efforts to cleanse Bourgogne from the 'plague of heresy' introduced by preachers into the region.[140] The lieutenant-general ordered the council to undertake a survey of Dijon in which all heads of households would be asked to swear that they would live and die as Catholics. They also supplied him with a force of 500 men to expel from Dijon those who refused.[141] Tavannes would later boast in his memoires that he had expelled around 1500 valets huguenots from Dijon, largely Swiss and German immigrants.[142]

Of the cities roughly 500-600 Protestants, many fled the city before the government of Dijon could begin to suppress them.[143]

Mâcon[edit]

After the Protestant seizure of Mâcon in Bourgogne, the lieutenant-general of Bourgogne Tavannes prepared to counter-attack. He requested 200 militiamen from Dijon to support him in the attack against Mâcon, the Dijon council despatched 500 to him instead.[144] Mâcon fell to the royalists sometime before 2 September. This proved disheartening to Protestant refugees from Toulouse who fled to Genève.[145]

Auxerre[edit]

Upon the Catholic recapture of Auxerre a large scale massacre followed at the impetus of the troops. According to Protestant accounts around 100 people were killed.[146]

Tavannes campaign[edit]

Tavannes succeeded in gaining mastery over the Saône valley during June. He captured Châlon from the Protestant seigneur de Montbrun (who had taken the city on 31 May) then succeeded in capturing Mâcon by a surprise assault.[147][148] He further repulsed an attempted move of 6,000 Swiss soldiers out from Lyon, forcing them to retreat to the city.[149] He was assisted in these campaigns, by 4,000 Swiss of his own, which had arrived in June.[150]

Trois-Évêchés[edit]

In the Trois-Évêchés (Three-Bishoprics) the rebel Protestants attempted to undertake an attack on Verdun during 1562. The attack stalled before one of the city gates over which there was a niche featuring Mary. According to the defenders Mary turned to face them to indicate her support for their cause, and this began a tradition in the city.[151]

Poitou[edit]

In Poitou, the Protestants seized Fontenay, Luçon, La Châtaigneraie, Chantonnay, Le Puybelliard, Foussais, Monsireigne, Thiré and Pouillé. The Cathedral of Luçon was subject to a thorough sack of what could be found inside on 30 April. In the surrounding areas of pillaged churches only Protestant worship existed.[152] Catholic counter-attacks result in reprisals and revenge killings.[153] Fontenay was recaptured by Catholic forces in July 1562, the Protestants of the town either leaving or being arrested.[154]

Poitiers[edit]

Condé's manifesto reached Poitiers on 13 April. Initially the Catholics and Protestants of the city decided to collaborate in control of the gates. After the Catholics at the gates denied entry to a Protestant noble to the city, the Protestants took over the Tranchée gate and let in the troops of their co-religionists.[155] This was not however the end of attempts to compromise in Poitiers, and while there were incidents of iconoclastic violence, others swore to maintain the peace.[156]

Both sides manoeuvred to assure themselves of control of the château, and by May the receveur général François Pineau was in firm control of the château, while all the gates were in the hands of the Protestants. Condé dispatched the sieur de Sainte-Gemme as his governor of the city. After his arrival he confiscated all the gate keys, the valuables of the churches and insisted the Catholics disarm. He allowed troops under the seigneur de Grammont to pass through the city, and during their stay they sacked many of the churches. Despite Sainte-Gemme's overarching control of Poitiers, he lacked control of the château. Pineau resisted all attempts towards his removal.[156]

The sieur de Sainte-Gemme served as the rebel replacement to the royal lieutenant-general of Poitou, the comte de Lude, who responded by retreating to Niort.[157]

When forces under Saint-André and Villars arrived outside the city and began an attack, Pineau allied himself with the cities attackers, turning the guns of the château on the defenders of the city, aiding their victory. The siege of Poitiers lasted ten days. The victorious royal army subjected Poitiers to a thorough sack on 31 May.[158][159] Saint-André had the Protestant mayor Herbert hanged alongside many other Protestants of the city.[157]

Condé had entrusted a force under the command of La Rochefoucauld with frustrating Saint-André's campaign, however he was driven into Saintonge by Saint-André.[84]

Saint-Maixent[edit]

In Saint-Maixent the Protestants engaged in iconoclasm and then seized the church of the Cordeliers.[152] After some Protestants passed by on their way to Poitiers, the Protestants claimed that the Catholic prior of the town had committed an offence against their pastor during his prayers. He was arrested but this was not sufficient for the Protestants. They approached the mayor and échevins under arms, asking that the prior be handed over to them so they could kill him. Facing refusal they marched on the château but were dispersed by forces of the lieutenant Cherray.[160]

Angoumois[edit]

The Protestants seized Angoulême, Cognac and Aubeterre in the Angoumois. After the capture of the former, the tomb of the French king Jean II was subject to abuses. The other cities were subject to looting also.[161]

After the royal recapture of Poitiers, the Protestant held cities of Angoulême and Cognac were recaptured, each one witnessed reprisals and violence with its recapture.[161]

Saintonge[edit]

The Protestant nobility of Saintonge came together in April and chose Saint-Martin de La Coudre as their leader. In combination with forces from neighbouring Poitou and the Angoumois this force marched north to rendezvous with Condé at Orléans. The nobility had taken the lead over the clerical elements of Protestantism, which in Saintonge had met in Saint-Jean-d'Angély to issue the call to arms.[162]

Saint-Jean-d'Angély[edit]

A Protestant synod of some description was held in Saint-Jean-d'Angély on 25 March. Noblemen and ministers were present for a discussion as to whether armed resistance was justified in response to the 'captivity' of the royal family and to defend liberty of conscience (Kingdon notes that at this time Guise and Navarre had yet to assume control of Catherine and Charles).[163] The assembly concluded that they did possess the right in that circumstance to assume arms. The call to arms also pre-dated the seizure of Orléans.[164]

During October, the comte de La Rochefoucauld was in the process of besieging Saint-Jean-d'Angély until word arrived of the defeat of the seigneur de Duras by Monluc, and he hurried to put himself at the head of the remaining Protestant forces from the battle so they could still make it north to Orléans.[165]

Aunis[edit]

La Rochelle[edit]

In La Rochelle, a degree of order was maintained at first. Though the city elected a Protestant mayor in response to the massacre of Wassy, the governor assured Catherine the city was largely composed of good men. He urged Catherine to further expand religious liberties, and reinforce his gendarmerie to keep the peace in the city. Neither request was responded to. Condé's appeal for financial aid was answered by a Rochelais pastor, but Jarnac and the council were able to counter this by having him expelled. On 31 May a wave of iconoclastic violence swept La Rochelle with many churches being sacked. The Protestant mayor and Jarnac condemned the acts.[166] La Rochefoucauld entreated La Rochelle and Jarnac to declare for Condé over the course of several embassies however Jarnac refused and the council sent deputies to the king professing their loyalty to the crown. La Rochefoucauld decided to organise a coup in La Rochelle, however it was discovered shortly before it was due to go off on 26 September. Jarnac confronted the rebel Protestants firing on them with cannons from the arsenal, driving them from the city.[167]

After the failure of this conspiracy, the duc de Montpensier, who was commanding royal forces in Guyenne, made known his desire to visit La Rochelle. To assuage urban concern he promised it would only be with a personal retinue of 40 men. This was a lie, and along with Jarnac, who was aggrieved by La Rochefoucauld's attempted coup, he introduced several hundred of his soldiers into La Rochelle disguised as common people. On 27 October they assumed control of the city and allowed a regiment of Montpensier's troops into La Rochelle.[167] In the wake of the coup, Jarnac became loathed by many in La Rochelle, and he left on 3 November, threatened with assassination. Montpensier banned Protestantism in La Rochelle and expelled Protestant pastors. He further deposed the Protestant mayor. The moderate Protestants of La Rochelle were driven into the arms of the more radical. The residents of the city unable to militarily oppose Montpensier's force raised an indemnity of 10,000 livres which persuaded him to leave on 15 November, leaving behind a garrison of 1,200 men.[168] On 27 December citizens of La Rochelle attacked the garrison, seizing gates and towers in such a way as to divide the force in the city. The captains fled La Rochelle, and the remains of the garrison negotiated their withdrawal.[169]

Emboldened, an agent of La Rochefoucauld's attempted another coup in favour of Condé. On 8 February a small force of outsiders were introduced to La Rochelle and linked up with militant parts of the population.[169] La Rochefoucauld's captain would however become bogged down besieging a gate, allowing the former Protestant mayor to regroup the moderates and scatter the coup plotters. The captain and some of his subordinates were tried and executed for treason on the advice of the lieutenant-general Burie.[170]

Atlantic islands[edit]

On the Île d'Oléron the citadel of Saint-Pierre was attacked. On the nearby Île de Ré, the Protestants adopted an attitude of neutrality in the conflict. This did save them from being subjected to pillage and depredations by the Catholic commander Monluc and a monk named Richelieu.[160]

Berry[edit]

Bourges[edit]

Bourges was brought into the civil war in May, with its church being destroyed in the violence. The city was captured by the Protestants on 27 May.[89] The destruction was led by the troops under the command of the comte de Montgommery.[171] The grave of Louis XII's wife was violated. [129] As Montgommery's troops entered the city they had taken shots at the scene of the last judgement which was part of the city gates.[172]

Orléanais[edit]

Orléans[edit]

In Orléans, radical Protestants burned the preserved heart of the recently deceased king François II. His entrails were thrown to the dogs.[129][173] Busts of Louis XI and Louis XII that adorned the cities hôtel de ville were destroyed.[174] On 7 August a munitions depot in Orléans exploded, and Montmorency wrote that the situation was becoming dim for the rebel Protestants who were beginning to 'lose hope.[175]

One of the most senior Protestant captains, the seigneur de Piennes earned himself a poor reputation among his co-religionists by his conduct in Orléans.[66]

During 1563, after the conduct of morning prayers, the Protestant priests of Orléans would oversee the reinforcing of the cities fortifications.[176]

Cléry[edit]

In Cléry similar actions against the royal body were undertaken, with the tomb of Louis XI being violated.[173] A copper statue of the king was also decapitated. For some Protestants, Louis XI was a particularly objectionable king.[122]

Beaugency[edit]

Condé decided to strike at Beaugency in July and subjected the city to bombardment. A hole was made in the wall through which the soldiery was able to enter on 3 July.[177] The capture of Beaugency by Protestant forces on was accompanied by a bloody sack of the city. Rapes, murders and pillage followed.[178][179] Neither Protestant or Catholic households were safe from the rampage of the troops.[180] The Protestant captain La Noue commented that the soldiers had more fury for the civilian population than they did for the garrison of Beaugency.[177]

Bretagne[edit]

While Protestant captains, such as Louis d'Acingé the captain of Tréguier or Christophe du Matz, the captain of the diocese of Nantes, had been begrudgingly tolerated by Étampes in the years before the war, by 1562 the governor of Bretagne felt it necessary to purge them from the ranks. Instead of using the arrière ban to bring to bear a quantity of nobles, he would look instead for more carefully chosen companies to conduct his military efforts.[181] Indeed, during June he expressed to the crown that rather than feudal service he would rather have a paid army at his disposal.[182] During April the baron de Vassé took charge of Laval so that it could not be betrayed to the Protestant rebels. Étampes was aware of disorders in neighbouring Anjou, but wished to ensure that he would not be seen as overstepping his authority by launching campaigns across the provincial borders, and therefore wrote to the king to ask permission to campaign outside his governate. Well aware of the apprehensions of the governor to work across provincial borders, rebel Protestants tried to exploit the border area to avoid suppression, as with a band from Montaigu who crossed the border to sack a Breton church near Clisson.[183] In May Étampes announced that unless there was aggression against Bretagne from a neighbouring province, he would not strike out of the border, by this means he in part sort to appease the Protestants of Bretagne. In June Montpensier directly appealed for his support, but Étampes would not leave without royal instruction (he was also aware the terms of the arrière ban did not apply to service outside the home province of the noble).[184] Though on a pacific footing, Étampes had assembled a sizable force by this time, boasting around 7,000 men for the repelling of any thrusts by the English.[185]

With the successes of the royal army in July the pressure for Étampes to campaign into the interior lessened and indeed he received explicit royal orders in August that his priorities should be to fend off any potential English attacks from the north and maintain the peace in Bretagne. This policy was interrupted by the intrusion of the Protestant army of Montgommery into several parishes of the province around Pontorson.[184] Étampes returned to requesting of the court that he be granted permission to clear the effected border area of Protestants, and was supported in this by the Catholics of Pontorson who requested of him on 12 August that he provide support to ensure the town remained in royal hands. They highlighted if Montgommery captured Pontorson it would both allow for English landings on the mainland, but also enable him to menace Saint-Lô, Caen, Rennes, Dinan, Fougères, Le Mans and Angers.[186]

Étampes' Normandie campaign[edit]

In August Étampes wrote to the crown to protest that no further taxes be raised. He argued that those already imposed had caused Protestants to begin a new spree of iconoclasm.[187] As a result of the situation in Normandie, Catherine resolves that while the royal army would capture Protestant held Rouen, Étampes would be used for the purpose of restoring order in lower Normandie and rescuing the lieutenant-general Matignon.[185] Before departing on his campaign into Normandie, Étampes needed to be assured of the security of several châteaux and settlements where the Protestant Laval family had influence. He therefore imposed lieutenants with authority over the town and château de Vitre and those of Montfort.[188] Nobles who joined him on the campaign across the border into Normandie would be paid volunteers. Even with pay many nobles remained uninterested and Étampes looked to other men to form his army.[182] As he moved into Normandie he found himself at the head of around 3,500 men. Weak in artillery, he took two pieces on loan from Rennes alongside the arsenal of Lamballe. Aware of his plans the Protestants attempted to seize the arsenal, but without success. On 16 August his force arrived in Fougères, from there he made to Pontorson, securing the town on 26 August to the delight of the Catholics. In front of Ducey, a stronghold of Montgommery on 30 August he put it to siege. A few days later on 2 September he secured Avranches before capturing Vire from Montgommery on 6 September. As he got deeper into Normandie he found himself increasingly facing Protestant skirmishing parties, but he was able to brush them aside with ease. His force was augmented by troops under the command of two of the Lorraine brothers, the duc d'Aumale and the grand prieur. Matignon also offered a small force to his army. The joint presence of the lieutenant-generals of Normandie eased any concerns Étampes might have had about overstepping his prerogatives, he made a great show of deferring to Matignon and involving him in his processes. Over the coming month he moved back and forth over the conquered territories increasingly concerned with his supply situation.[189] Étampes' force arrived in Bayeux around October.[190] Étampes resolves to watch over four strongholds, Bayeux, Saint-Lô, Avranches, and Granville. Greatly concerned by his successes, Condé and Coligny urge Elizabeth to organise an invasion of Bretagne though this would not come to pass. By October's end Étampes resolves to join with the main royal army, and makes his way to join the besieging army in front of Rouen. He ensures that he avoids the governor of Normandie who was held up in Caen on his journey to the siege lines.[191] He would stay with the royal army until the end of the year, his troops distinguishing themselves in front of Paris, his nephew Martigues and the troops fighting at Dreux while Étampes remains with the royal family.[191]

Nantes[edit]

In April various measures were undertaken to reinforce the city of Nantes. The watch was increased, provisions audited and the cities water gate sealed. The Protestants would at first be allowed to maintain themselves in Nantes in line with the Edict of Saint-Germain. The Cathedral chapter was even unable to prevent the continued sale of Protestant literature.[192]

In Nantes, Étampes protested the diverse commands that were being sent out by the royal authorities. He complained that Navarre ordered him to seize the arms of the local Protestants while Montmorency urged him to drive Protestants from the territory.[193] Similar complaints about contradictory orders from the royal centre would be levied by the comte de Lude, the lieutenant-general of Poitou.[193] He further protested the royal suggestions that he fund himself by seizing the treasuries of Catholic held towns, which was argued to him on the grounds that it would prevent neutral Protestants from becoming rebels. He protested that this would be a cause for tumult.[194] Étampes warned that if he was forced to dismiss his men for lack of pay, they would join the rebels as they would 'follow the money'.[195]

In July, Étampes held a disputation between several Protestant and Catholic notables at the château de Nantes. As with Poissy this failed to find any unity, however his aim was to show that coexistence was possible, clients of Rohan and Andelot were invited, who may have been tempted to join with their patrons in rebellion.[192] In August Étampes and Martigues had to depart from Nantes to fight rebels in southern Normandie. Recognising things might descend into violence without his presence, Étampes ordered a prohibition of Protestant worship before he left.[196] That month royal orders arrived in Bretagne ordering the removal of all Protestant ministers from the province, these orders were received by the governor of Nantes, Sanzay.[197] The bourgeois of Nantes attempted a purge of suspected Protestants from the présidial court. While many Protestants of Nantes fled to Protestant strongholds such as Blain, some remained and continued to practice in Nantes. Protestantism continued to be tolerated as long as it was in the privacy of ones home and did not involve public non-conformity.[198] With the threat of an English presence on the Loire a captain de La Tour was despatched by the crown to protect Nantes with a request that 300 soldiers be raised for him. Sanzay however preferred to rely on a local militia, and expanded this body to 400 men. He complained to Étampes that La Tour's force was an unnecessary burden on the city.[197] By December he protested that he lacked funds to pay the garrison, the château was devoid of provisions and his orders were increasingly disregarded.[199]

Guérande, Blain and La Roche-Bernard[edit]

In these towns where Protestant lords held sway, the massacre of Wassy was responded to with the assumption of arms and the strengthening of defences. However this did not precipitate fighting.[200] Blain in particular, a fief of the Rohan family was fortified.[201]

Dinan[edit]

Étampes was suspicious that the captain of Dinan, Jacques de Forsans was a Protestant, there was therefore a risk that he could betray the town to the Protestants. He could not however dismiss the captain, who enjoyed close relations to the Albret and Navarre families. Therefore, Étampes installed a lieutenant for the town named Jean de Rieux, sieur de Châteauneuf whose authority would supersede the captains. The captain was greatly aggrieved by this usurpation but resigned himself to his situation submitting to Rieux's command of the town.[202]

Though he had protested his loyalty to Étampes after the appointment of Rieux, a month later when Rieux began to impose himself more fully on Dinan with a review of the nobility he had mobilised, Forsans defected to the Protestant rebels.[203]

Belle Île[edit]

During the war, the governor of the island of Belle Île was offered command of the town of Vire by one of the lieutenant-generals of Normandie (the seigneur de Matignon, but declined. He justified his refusal by his fear that if something were to happen in his governate in his absence he would find himself in trouble.[204]

Brest[edit]

A captain of 100 soldiers in the city of Brest was found to be absent from his charge, Étampes therefore had them replaced by the captain of the city, Jérôme de Carné.[204]

Île de France[edit]

Paris[edit]

During the war Paris would be entrusted first to the lieutenant-generalcy of the comte de Brissac in May, before being transferred to his brother, the seigneur de Gonnor a few months later. Both men worked to protect the capital against threats, and acted as intermediaries between the royal family and the administration of the city.[205]

In May there was a scare that the Protestants were about to stage an attack on the capital, however it turned out to be a simple quarrel between some boatmen. Nevertheless, the Parisians had already chained the street in preparation for the attacks.[206] On 28 May the cardinals de Guise and de Lorraine carried the Ciborium aloft in a procession through the city, every corner crowded with soldiers from Metz and Calais.[207] Due to the fact the king had departed Paris, the remaining Protestants in the city were ordered to depart by Navarre within 48 hours on 26 May. He declared that their property was forfeit, which was met with delight in the capital.[208] Those who chose to stay to protect their property or because they couldn't leave were ordered to convert or leave immediately. The rebaptism of a Protestant girl into the Catholic faith was attended by 10,000 Parisians.[209] Book burnings were undertaken at the place Maubert, and the Catholic population enjoyed firebrand preaching from the cardinal de Lorraine. Lorraine chose a sermon which affirmed the real presence while the Papal nuncio stood by.[209] Processions against heresy were undertaken.[210] In June, the Paris parlement undertook to receive confessions of Catholic faith from all its judges. 31 of the courts 143 members chose to absent themselves on the day that the public declaration of their Catholicism was to be made. While this does mean all 31 were necessarily Protestant, it was a not insignificant minority of the courts membership.[211] Even among those who did not absent themselves, there were those who were suspected of Protestant sympathies, such as Christophe de Harlay.[212] The université de Paris followed on from the example of the parlement in requiring oaths of Catholicism.[213] After an incautiously worded declaration from the Paris parlement, vigilante killings began in July. Suspected Protestants were given mock trials and killed, or struck down in the street.[214] For example, during the procession on the feast of the holy-innocents, an observer who made an incautious comment was murdered by those around them.[215] The parlement revoked its edict and insisted on the following of regular legal channels.[213] Houses that were not draped in tapestries were subject to looting.[209]

The violence was in part motivated by developments around Paris. When nearby Meaux was seized by the Protestants, fuelling paranoia that the cities food supply would be cut off. Measures were taken to ease potential food shortages. It was now ordered that even Protestants who had converted to Catholicism were to leave the city, searches were undertaken for arms.[214] The prisons of Paris filled with religious prisoners, so much so that they could not be fed and began to starve in the petit châtelet. Some arrests were undertaken solely to protect individuals from the wrath of crowds.[216]

On 28 January a gunpowder store detonated in the arsenal. It caused significant damage to the surrounding houses, and as a crowd gathered to look at the damage word spread that the explosion had been set off by the Protestants. Before the arrival of Marshal Montmorency the crowd had killed at least one. Another several would be killed the following day.[217]

Provence[edit]

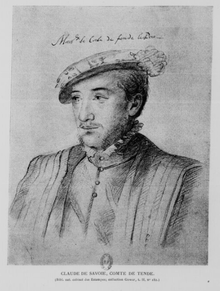

In Provence, the governor the comte de Tende was not openly Protestant, but was at least sympathetic to Protestantism. His second son the comte de Cipierre and second wife Françoise de Foix-Candalle were both openly Protestant.[218] In opposition to the governor and the comte de Crussol, the seigneur de Flassans who had been pushed out of Aix destroyed a royal company and pillaged the countryside around the city.[219] In early March Tende was able to defeat Flassans' forces, that had terrorised the Protestants of Provence during 1561. Flassans was driven out of Provence by a combined army of Tende and Mauvans.[220] Flassans defeat came despite the 500 reinforcements he had received.[221] Tende, Mauvans and Crussol sacked the Flassans stronghold of Barjols on 6 March. Tende did not approve of the massacre that followed, and entrusted his son in law Jacques de Cardé with stopping the violence. Flassans himself was able to escape the slaughter of his men. He fled to the Île de Porquerolles. [222][223][220] In the wake of the massacre of Barjols, Crussol's commission was challenged at the court on the grounds of his Protestant sympathies.[219]

After the defeat of Flassans, Flassans' brother, the comte de Carcès recruited Tende's eldest son who had remained Catholic to the radical cause.[221] Therefore, in May his eldest son, the lieutenant-general of Provence, the seigneur de Sommerive declared himself in rebellion against his father. He wrote a letter to his father announcing this decision as his 'very humble, very obedient, and very sorry son and servant'.[221] Sommerive secured the rallying of the majority of the important city governors of Provence in opposition to the comte de Tende. Tende had raised levies, but was soon forced to disband them due to his inability to pay them. The disbanded troops spread out as gangs attacking Protestants across Provence.[224] Tende wrote mournfully to Catherine bemoaning how divided the province was.[225] In Aix, the Protestant members of the garrison disrupted a Catholic procession by throwing grains into the path it was to take, causing injury to the bare footed pilgrims. Tende was unable to prevent the Catholic counterstroke, which was to massacre the Protestants of the city, even when he appealed to the parlement in the city.[226][227] Six of those parlementaires who had supported the registration of the edict of Saint-Germain fled the city, while the seventh was murdered.[228] The parlement chose to recognise Sommerive as the governor of the province. Sommerive declared the arrière ban, raised taxes and announced that his father was a captive of the Protestants, making his orders null. Both Aix and Marseille fell under his control, and he received troops from the Papal States.[229] Catholic successes began in Provence earlier than they did in the rest of the south. Thus it was on 6 June that Orange was recaptured from the Protestants by a combined force of Carcès in alliance with the Papal commander Fabrizzio Serbelloni. The capture was accompanied by a bloody series of reprisals.[178] Naked corpses of raped women were hanged from trees, and pages of the gospel were stuffed into the mouths of the dead.[230] The violence was largely undertaken irrespective of religion, the Papal army butchering both Catholics and Protestants.[131] In response to this coup, having been informed by Provençal Protestants of the Papal brutality, the baron des Adrets invaded the Papal States in July.[149][180] Alongside Carcės, Sommerive then proceeded to drive Tende from the province, forcing him into exile in Savoia. The Protestants would take refuge in Sisteron during September.[231] When put to siege by the Catholic forces, the comte de Cipierre would face off against his elder brother Somerive.[232] Sisteron fell to the Catholic forces that same month. Its fall would see brutal reprisals carried out against those inside the town including further instances of sexual violence.[233][178][234]

Aix[edit]

By July some of the consuls that had been purged by the commissioners were reinstated to their charges. This process was completed in September, with Flassans returning to his office.[235]

Mornas[edit]

After the Protestant capture of Mornas by a force under the command of Montbrun on 8 July, the defenders of the city would be massacred, their corpses put into the river with a sign which urged the people of Avignon to let the corpses pass as they had 'paid the toll' of Mornas.[178][111]

Noves and Saint-Rémy[edit]

Crussol's troops in Provence which were stationed at Noves and Saint-Rémy were accused of mistreating the towns priests and elements of the population. Crussol responded to reports of this behaviour by ordering his captain at Saint-Rémy to respect the people of the town.[236]

Guyenne[edit]

In Guyenne, Condé entrusted the seigneur de Duras as his deputy. Initially the wave of Protestant urban seizures completely overwhelmed the Catholic commander Monluc. He marched towards Montauban only for it to defect to the Protestants, he then heard that Agen was also with the rebels. He moved then towards Villeneuve d'Agen and Port-Sainte-Marie, finding similar situations in both. Monluc, a man of pitched battles, had to adapt to the new style of warfare by urban coup. Only Bordeaux stood for the king in Guyenne.[231]

Monluc's campaigns[edit]

In April 1562, the Catholic commander and future Marshal of France Blaise de Monluc took Villefranche at the request of Cardinal d'Armagnac, by this means Catholic worship was re-established in the cities churches.[125] Viewing the local authorities as insufficiently harsh he intervened to have several hanged from the town hall windows.[117] In the summer of 1562, Monluc began a campaign against the queen of Navarre in southern France. Unlike the royal court, he recognised the danger of the Albret dynasty with their deep ties and connections in the south.[237]

Navarre had learned of the iconoclasm that had transpired during his wife's stay in Vendôme on 21 May and was furious. His immediate plan was for Charles to have her lands handed over to him and for her to be sentenced to life imprisonment.[238] Having established herself in Pau a secretary was despatched south to her by Navarre. Navarre was aware Felipe would want the annexation of Navarre to be accomplished legally.[239] This secretary brought with him a procuration allowing Navarre to trade her rights to the kingdom of Navarre for a new kingdom Navarre was to gain from the Spanish in Sardinia. Navarre was informed of the great wealth of Sardinia, abundant in pasture and cities.[240] With royalist troops in Guyenne, and the Spanish to her back, the queen of Navarre signed, though included a secret disclaimed allowing her to re-open the discussion at a later date.[241] The declaration would never be delivered to the king of Navarre prior to his death regardless.[242] The king of Navarre meanwhile instructed Monluc to see to his wife's capture, but Monluc was unable to intercept her before she reached her seigneurial lands in Béarn.[243]

Monluc developed a reputation for brutality. Protestant pastors and laymen were summarily executed under his orders either by being hanged or thrown into wells.[244] The commander bemoaned that the poor state of his soldiers pay forced him to ransom prisoners as opposed to executing them all.[150] For Monluc the brutality was a necessary part of warfare given the risks that faced royal authority in times of rebellion.[245]

Monluc aided in the preservation of Toulouse and Bordeaux for the royalist cause. As concerned Toulouse he had been able to prevent Protestant reinforcements under the seigneur de Lanta and Arpajon from making it to the city.[246] He had hurried to Bordeaux in early June to provide support for the seigneur de Burie who was having difficulty holding the city.[247] On route to Bordeaux he was told by a representative of the queen of Navarre's that the situation in the city was fine, and that she had left France to her sovereign lands to cool tensions. This left Monluc in a difficult position, unsure whether the court would approve of an aggressive attitude towards the queen's territories.[248] On 3 July he captured Castelvieux with the support of Spanish forces who would be a continual asset to him during his campaign.[249] In August he took Monségur and had the garrison executed, including a captain he had served with in the Italian Wars. He also captured Penne during this month. This was followed with the capture of Terraube in September during which a general slaughter of the population was undertaken, the bodies thrown into the well.[117] On 9 September, Réalville fell to him.[249] Monluc then recaptured Bergerac, Sainte-Foy and Lectoure (2 October), which had been taken by the Protestants.[250][149][251] His conquests were accompanied by hundreds of deaths.[252] In Bordeaux, he installed his protégé Tilladet who took charge of the town's Catholic league (which dated back to 1560) and allied with a league under the comte de Candalle later during the war.[229][102][253]

Monluc was kept from invading Navarre's sovereign lands by Catherine, on the understanding that the queen of Navarre would maintain a technical neutrality in the conflict. From his base at Agen, Monluc therefore focused his attentions in the south against local Protestant forces.[254] The local Protestant commander Duras who commanded around 4,000 soldiers was advised by the queen of Navarre to retire to Orléans.[255] Though she framed this in correspondence with Catherine as evidence of her desire for peace, it conformed with the rebel strategy for forces to be concentrated at Orléans.[248] Duras ignored the advise to proceed to Orléans and instead made an assault on Bordeaux which failed.[251] After this he decided to hunker down at Montauban, the final major city held by the Protestants in Guyenne with his consolidated force of around 8,000 men.[256] Catherine was not idle however, and re-installed Monluc and the local sénéchaux with military authority over the Albret lands of Armagnac and Foix. The queen of Navarre's bishops were warned they would forfeit their office if they did not return to Catholicism.[257]

The presence of Spanish forces in Pamplona and Fuenterrabia served to dissuade another Protestant commander, the seigneur de Grammont, who headed Gascon infantry from proceeding north to join with Condé.[258][259]

With orders to rendezvous with Condé, Duras began to make the way north.[256] Monluc first fought the Protestants in a battle from 5–8 October on the Dordogne with the support of a Spanish contingent under don Carbajal.[249] On 9 October Monluc intercepted the Protestant army of Duras at the Battle of Vergt in the Périgord and came out the victor. Duras lost about 1,400 men in the battle and his army was prevented from unifying with the main Protestant force.[233][256] Thompson attributes the Protestant defeat at the battle of Dreux to the battle of Vergt.[150] La Rochefoucauld took the battered remnants of Duras' force north to Orléans.[149] After his departure from towns in the Périgord Monluc endeavoured to leave in his wake leagues of gentleman to assume military control and protect against any counter-attack.[250]