European printmaking in the 20th century

Twentieth-century art underwent a profound transformation: in a more materialist, more consumerist society, art was directed to the senses, not to the intellect. The avant-garde movements arose, which sought to integrate art into society through a greater interrelation between artist and spectator, since it is the latter who interprets the work, being able to discover meanings that the artist did not even know.[1]

The most commonly used graphic methods were woodcut, lithography, etching and silkscreen printing, and new techniques such as color aquatint were developed.[2] The offset printing also emerged, which revolutionized graphic art. Offset is a process similar to lithography, consisting of applying an ink on a metal plate, usually aluminum. It was the parallel product of two inventors: in 1875, the British Robert Barclay developed a version for printing on metals (tin) and, in 1903, the American Ira Washington Rubel adapted it for printing on paper.[3]

France[edit]

Voillard[edit]

At the turn of the century, the art dealer and gallery owner Ambroise Vollard became a significant publisher. In 1890 he opened a gallery in Paris, where he exhibited the work of artists such as Paul Gauguin, Henri Matisse, Paul Cézanne and Pierre-Auguste Renoir. In 1901 he organized the first exhibition of works by Pablo Picasso. Vollard was especially concerned with promoting the work of marginal artists, artists rejected by the official salons. A true lover of prints, his success in the sale of paintings allowed him to subsidize the editions of prints purely out of personal interest, since it rarely brought him profits. He was also concerned about the quality of the productions, always trying to have the best materials and the best technicians.[4]

Most of Vollard's production focused on limited editions for collectors, made by the best artists of the day. Another field of publishing for Vollard was the illustrated book for bibliophiles, of which he promoted twenty-two projects between 1900 and 1939. Vollard always selected the artist, whom he sometimes let select the text he would like to illustrate. His first edition was Parallèlement by Paul Verlaine, illustrated by Pierre Bonnard, which was a commercial failure, as was the next, Daphnis and Chloe, also by Bonnard. Made in lithography, for the next edition he opted for the woodcut, more appreciated by collectors: Imitation of Christ, illustrated by Maurice Denis, was a sales success. Among his subsequent editions, the following stand out: Les Amours by Pierre de Ronsard (1915, Émile Bernard), Les Fleurs du mal by Charles Baudelaire (1916, Bernard), Œuvres de maistre François Villon (1919, Bernard), Les Petites Fleurs de Saint François (1928, Bernard), Les âmes mortes by Nikolai Gogol (1924–1925, Marc Chagall), Les Fables by La Fontaine (1926–1931, Chagall), La Belle Enfant ou L'Amour à quarante ans by Eugène Montfort (1930, Raoul Dufy), L'Ancien Testament (1931–1939, Chagall).[5]

During the First World War, due to the difficulty in finding quality materials, he had to resort to photoengraving for some of his editions. Even so, he achieved quality products, especially thanks to the collaboration on the artistic side of Georges Rouault. Vollard's first collaboration with this artist took place in 1912, when Rouault offered him to edit a Miserere on which he was working; Vollard bought it in exchange for illustrating a book written by the dealer himself, Les Réincarnations du Père Ubu, which would not see the light until 1932. The Miserere (1916–1927) is one of the most original and creative series of prints of the 20th century, in which the artist combined different techniques: the drawing was transferred to copper plates by means of heliogravure, on which Rouault worked with acid and etching tools, achieving unique tones and values in the history of printmaking.[6] In the 1920s, Vollard resumed publishing original prints, publishing works by Georges Braque, Marc Chagall, Raoul Dufy, Jules Flandrin, Tsuguharu Foujita, Aristide Maillol and Maurice de Vlaminck.[7] His last two editions, before his death, were of works by Rouault: Cirque de l'étoile filante (1938) and Passioné (1939).[8]

Picasso[edit]

Vollard's best editorial fruit was undoubtedly his collaboration with Pablo Picasso, which gave rise to one of the best series of prints made in the century: the Vollard Suite. Picasso started making prints in Barcelona, where in 1899 he made The Left-Hander, a work that did not fully satisfy him. He continued his graphic work in Paris, where he was influenced by Toulouse-Lautrec, as can be seen in his poster for Els Quatre Gats or his illustrations for the magazines Joventut and Catalunya Artística. In 1904, installed in Montmartre, he made La comida frugal, an original composition that he elaborated in copper plate, where he portrays the misery of a poor couple. The following year he elaborated the series of Saltimbanquis, one of his favorite subjects of the rose period, a set of fourteen prints published by Vollard in 1913. From then until 1920 he only made prints sporadically and on commission, mostly by friends of his, such as the Poems by André Salmon (1905), the Saint Matorel by Max Jacob (109–1910)—already in cubist style—and The Siege of Jerusalem, also by Jacob (1914). In 1922 he produced a series of Bathers, published by Marcel Guiat.[9]

In the 1920s, Picasso's relationship with Vollard grew closer: a series of etchings made by Picasso in 1927 on the theme of the artist and his model was acquired by the dealer to illustrate The Unknown Masterpiece by Honoré de Balzac, published in 1931. It was then that Vollard commissioned a series of prints that the artist produced between 1930 and 1937, and which was published in 1939: the Vollard Suite. It is a set of one hundred prints—most of them etchings and some drypoint—of diverse subject matter, divided into several sequences; the largest (about forty) revolve around the theme The sculptor's workshop, centered on the relationship between a sculptor, his model and his work, an autobiographical reference in which the model is Marie-Thérèse Walter, his partner at the time; another group revolves around the theme of The Rape, while there are several dedicated to the figure of The Minotaur, among which stands out Blind Minotaur in the Dark, considered one of the best of the series; there are also three portraits of Vollard. At the same time, in 1931 he illustrated for the publisher Albert Skira The Metamorphoses by Ovid. In 1935 he made La minotauromaquia, an etching on copper plate, where he takes up again the figure of the minotauro; it is considered one of the stylistic precedents of Guernica. Between 1936 and 1937 he illustrated Historia natural by Buffon (published in 1942), again commissioned by Vollard, a set of thirty-one sugar etchings in a realistic style. In 1937, he made Sueño y mentira de Franco, a set of eighteen small vignette-like images engraved on two copper plates, as a denunciation against the Spanish Civil War and against Francisco Franco; a thousand copies were printed and sold at the Pabellón de la República Española of the Exposición Internacional de París of that year.[10]

After a few years of graphic inactivity, after World War II he took up lithography, generally on zinc plate. Between 1945 and 1951 he made several portraits of Françoise Gilot, his new partner, mother of his children Claude and Paloma. During this period he also tackled subjects such as fauns, doves and still lifes, as well as several versions of Cranach's Susanna in the Bath. Among his works of those years stand out: La mujer sentada y la mujer dormida (1947), Retrato de Góngora (1947), Los faunos músicos (1948) and his famous Paloma (1949), which was taken as the logo of the World Peace Congress. Since 1955, his relationship with Jacqueline Roque, his second wife, led him to a stylistic turn, whereby he returned to expressionist deformation and grotesque and erotic themes. His love for bullfighting returned and, in 1957, he illustrated the life of the bullfighter Pepe-Hillo, working mainly in linoleum. In 1966 he returned to etching, with an increasingly sexual theme, in which the women are huge, fat figures. Between 1970 and 1971 he produced a series of 156 prints for the Leiris gallery, generally of women lying down and men looking at them.[11]

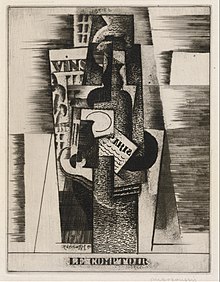

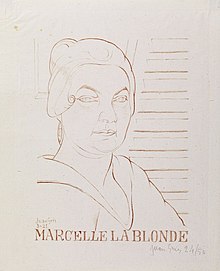

Picasso was the most prominent representative of Cubism, a movement based on the deformation of reality through the destruction of the spatial perspective of Renaissance origin, through an organization of space according to a geometric plot, with simultaneous vision of objects and a range of cold and muted colors. The members of this group contributed a new conception of the work of art, thanks to the introduction of collage.[12] Other exponents of this movement in the graphic field were Georges Braque, Juan Gris, Louis Marcoussis and Jacques Villon. Braque was, together with Picasso, the father of cubism. His printmaking started late, once he had already abandoned cubism and in a neoclassical style, as can be seen in his etchings for the Theogony of Hesiod (1931).[13] The Spaniard Juan Gris began in humorous drawing in magazines such as Le Charivari and Le Cri de Paris. In 1912 he switched to cubism, with an orthodox style but with a strong personality. He produced thirty-four lithographs and etchings, in compositions similar to his pictorial work.[14] He illustrated several books: Ne coupez pas, Mademoiselle, ou les erreurs des P. T.T. by Max Jacob (1920), Mouchoir des nuages by Tristan Tzara (1925), A Book concluding with as a wife has a cow a love story by Gertrude Stein (1925) and Denise by Raymond Radiguet (1926). He also did some portraits in lithography (Marcelle la Brunette, Marcelle la Blonde, Jean the Musician).[15] Marcoussis went through Impressionism and Fauvism before arriving at Cubism. A virtuoso draughtsman, he worked as a caricaturist for several newspapers. He began printmaking in 1912, but devoted himself more intensely to it between 1930 and 1940: Aurelia by Gérard de Nerval (1930), Tables of Salvation (1931), Alcoholes by Apollinaire (1934–1935), plus a hundred portraits (Gertrude Stein, 1934; Miró, 1938).[16] Villon, brother of Marcel Duchamp, was initiated into printmaking at the age of six by his grandfather, Émile Nicolle. Gifted in drawing, he worked for several newspapers and magazines. From 1899 he engraved for the publisher Edmond Sagot; among his first works are the series Minnie's Bath (1907) and Nudes (1909–1910). Already in the cubist period he made his Equilibrista (1913), one of the best prints of this style. In 1920 he made Tablero de ajedrez, a reproduction of the painting of the same name. The following year he illustrated the Architectures by Paul Valéry. Between 1923 and 1930 he made reproductions of works by Picasso, Matisse, Cézanne, Renoir and Van Gogh to make ends meet. In 1939 his Three Orders wqas followed by series of landscapes, among which his Orchards series (1940–1941) stands out. Later, Cuarto de buey (1941) and Globo celeste (1944) stand out.[17]

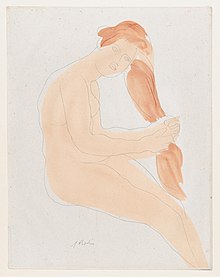

Cubism was one of the first avant-garde movements, together with Fauvism and Expressionism. Fauvism involved experimentation in the field of color, which was conceived in a subjective and personal way, to which they applied emotional and expressive values, independent of nature. For these artists, colors had to generate emotions, through a subjective chromatic range and brilliant workmanship.[18] Prominent among their ranks was Henri Matisse, who practiced lithography, generally with the collaboration of the printmaker Auguste Clot. Between 1906 and 1913 he produced a series of lithographs in which he denotes the influence of Rodin, with a linear, fluid and elegant language.[19] Other exponents were André Derain, Raoul Dufy and Maurice de Vlaminck. Derain engraved mostly on wood, in illustration of books such as Apollinaire's Enchanter rotting (1909), Max Jacob's Les Œuvres burlesques et mystiques de Frère Matorel, mort au couvent de Barcelone (1912), André Breton's Monte de Piedad (1916) and Antonin Artaud's Heliogabalo (1934).[20] Dufy began in woodcut (Bestiary of Orpheus by Apollinaire, 1910), to switch to lithography after World War I (La Belle Enfant ou L'Amour à quarante ans by Eugène Montfort, 1930, for the publisher Vollard).[21] Vlaminck, self-taught, produced woodcuts and lithographs, in a style similar to his paintings, which are difficult to classify chronologically, as he never dated them.[22]

Germany[edit]

Expressionism emerged in Germany. As a reaction to Impressionism, the Expressionists advocated a more personal and intuitive art, where the artist's inner vision -the "expression"- predominated over the representation of reality -the "impression"-. In their works they reflected a personal and intimate theme with a taste for the fantastic, deforming reality to accentuate the expressive character of the work. It was an eclectic movement, with multiple tendencies at its heart and a diverse variety of influences, from post-impressionism and symbolism to fauvism and cubism, as well as some aniconic tendencies that would lead to abstract art (Kandinski).[23]

Its first reference was the group Die Brücke, founded in Dresden in 1905 by Ernst Ludwig Kirchner, Fritz Bleyl, Erich Heckel and Karl Schmidt-Rottluff; later Emil Nolde, Max Pechstein and Otto Mueller joined. Influenced by German Gothic—Kirchner studied Durero's woodcuts in depth—African art, Arts and Crafts, Jugendstil, the Nabis and artists such as Van Gogh, Gauguin and Munch, were interested in a type of subject matter centered on life and nature, reflected in a spontaneous and instinctive way, so their main themes are the nude -whether indoors or outdoors-, as well as circus and music-hall scenes, where they find the maximum intensity they can extract from life.[24] Die Brücke gave special importance to graphic works: their main means of expression was woodcut, a technique that allowed them to capture their conception of art in a direct way, leaving an unfinished, raw, wild look, close to the primitivism they admired so much. These woodcuts present irregular surfaces, which they do not disguise and take advantage of in an expressive way, applying spots of color and highlighting the sinuosity of the forms. They also used lithography, aquatint and etching, giving reduced chromaticism and stylistic simplification.[25]

Its main exponent was Kirchner, a temperamental artist who left one of the most relevant graphic works of the first half of the century. His early works denote the influence of Japanese printmaking and Félix Vallotton: Man and Woman (1904), Bathers (1906). In 1915 he illustrated Peter Schlemihl's Peter Schlemihl by Chamisso. A prolific author, he left 971 woodcuts, 665 etchings and 458 lithographs, mostly landscapes, nudes, portraits and self-portraits, as well as a considerable output of distinctly erotic content.[26]

The second phase of German Expressionism was the group Der Blaue Reiter, founded in Munich in 1911, where a number of artists were grouped together who rather than a common stylistic stamp shared a certain vision of art, in which the creative freedom of the artist and the personal and subjective expression of his works prevailed.[27] Its main exponent in graphic art was Vasili Kandinsky, a Russian artist initiated in the Jugendstil and who, since 1908, was evolving towards abstraction, in paintings where the importance of the work resided in the form and color, creating pictorial planes by confrontation of colors.[28] He practiced mainly woodcut and lithography, generally colored. One of his first works was the poster for the 1st Exhibition of the Phalanx in 1901, an association of artists he had founded in Munich. It was followed by woodcuts such as The Singer (1903), Farewell (1903) and The Night (1903). Between 1908 and 1912 he wrote several lyrical texts that he published accompanied by woodcuts (Sonidos, 1913). In 1909 he also made the woodcut series Poemas sin palabras and Xilografías. In 1911 he wrote and edited De lo espititual en el arte, a theoretical book that he accompanied with woodcut illustrations, already close to abstraction. Between the end of 1915 and the beginning of 1916 he produced in Stockholm a series of etchings of grotesque tone, which he exhibited at the Gummeson Gallery. During his stay in Russia, until 1921, he continued with this technique. Back in Germany, where he taught at the Bauhaus, he made the series Small worlds (1922), consisting of twelve prints (lithographs, woodcuts and etchings) that emulate his pictorial universe.[29] He also theorized about printmaking in Point and Line on the Plane (1926), where he postulated that each of the three main graphic techniques has specific characteristics both formally and sociologically.[30]

Another member of Der Blaue Reiter was Franz Marc, an artist who died prematurely in the world war. Particularly interested in the representation of animals, with which he symbolized communion with nature, he left sixty-three prints, made between 1908 and 1916.[31] Also worth mentioning is the sculptor Ernst Barlach, who was also an engraver and playwright. His graphic work spanned from 1910 to 1930, in lithography and woodcut: in the former technique he illustrated his own dramas (Der Tote Tag, 1912; Der arme Vetter, 1919), while in the latter he produced more stylized images (Der Kopf, 1919; Walpurgisnacht, 1923; Lied an die Freude, 1927).[32] In Austria, Oskar Kokoschka, an expressionist of personal inspiration, stood out, author of such lithographic series as Dreaming Children (1908), King Lear (1963), Odyssey (1963–1965), Saul and David (1966–1968) and Trojans (1971–1972).[33]

In Germany, after World War I, the group Neue Sachlichkeit (New Objectivity) emerged, which, as a reaction movement against expressionism, returned to realistic figuration and the objective representation of the surrounding reality, with a marked social and vindictive component.[34] Its main representatives were Otto Dix, George Grosz and Max Beckmann. Dix denounced in his works the brutality of war and the depravity of a decadent society. In his series of etchings The War (1924) he made a powerful anti-war plea, with crude images of intense realism.[35] Grosz worked as a caricaturist before the war, so his style reflects the properties of that genre, marked by linearity. His images denounce social hypocrisy, with ugly and caricatured figures, generally in profile.[35] He was the author of the series Gott mit uns (1920) and Ecce homo (1923), in which he portrayed a society dominated by stripes, frock coat, cassock and safe.[36] Beckmann showed a strong influence of German Gothic. In 1909 he produced the lithographic series The Return of Eurydice, but soon after switched to drypoint (Small Self-Portrait, 1912). During the war he made a series of prints showing the drama of war: Declaration of War (1914), Granada (1915). After the war he followed a realistic line in which he continued to show the drama of war, as in the lithograph series Viaje berlinés (1922). He then produced portraits, still lifes, landscapes, nudes and circus themes (Funámbulo, 1921). In 1947 he settled in United States, where he evolved to a personal style of symbolic and dreamlike cut (Day and Dream, 1946).[37]

The Bauhaus School, was founded in 1919 by Walter Gropius, who took over the direction of the School of Arts and Crafts in Weimar and reoriented it towards a multidisciplinary curriculum that addressed both architecture and design and decorative arts; students at the school learned theories of form and design, as well as workshops in stone, wood, metal, clay, glass, weaving and painting. The school moved to Dessau in 1925 and to Berlin in 1932, until the following year when it was closed by the school's management in the face of systematic harassment by the Nazi authorities.[38] At the school there was also a printmaking workshop, run between 1919 and 1924 by Lyonel Feininger, an American artist based in Germany. In his beginnings he worked as a caricaturist, with a modernist style inspired by Beardsley, Toulouse-Lautrec and Steinlen. He also went through cubism, expressionism and futurism. He worked mainly in woodcut, a technique that influenced the spatial organization of his pictorial production. His style is characterized by the use of large black masses and short, irregular lines, in parallel or convergent configurations that create volumes. He produced several series, among which Zwölf Holzschinitte (1923) stands out. After the closure of the Bauhaus he returned to his country, where he practiced lithography, especially in landscapes: Manhattan II (1951), Dorfkirche (1954).[39] Another teacher who practiced printmaking was Josef Albers, in charge of the school's preparatory course and glass painting workshop. He practiced woodcut, lithography, drypoint and linoleum, with a stylistic evolution ranging from expressionism to an abstraction of constructivist influence, in which he gave all the prominence to the straight line and a black and white chromaticism. He later settled in the United States, where he taught at Black Mountain College and Yale University, where he produced his Structural Constellations series (1953–1958).[40] Another teacher was Oskar Schlemmer, successively director of the workshops of stone sculpture, mural painting and theater. After passing fleetingly through expressionism and cubism he evolved towards abstraction, with images in which he reduces the human figure to linear outlines, within a geometric composition.[41] The Bauhaus printmaking workshop produced in 1921 a five-delivery letterbook with works by Bauhaus teachers, as well as German, Italian and Russian artists. It also produced commissioned works, and many artists from outside the school printed their works there. In 1923 they also founded a publishing house, which among other works published the book for the Bauhaus exhibition of that year.[42]

Italy and Futurism[edit]

The next avant-garde to emerge was futurism, a movement of Italian origin that exalted the values of the technical and industrial progress of the 20th century and emphasized aspects of reality such as movement, speed and the simultaneity of action.[43] Its main representatives, Umberto Boccioni, Giacomo Balla, Gino Severini and Carlo Carrà, practiced printmaking very occasionally. It is worth mentioning in the graphic field Giorgio Morandi, an artist only temporarily ascribed to futurism and of personal evolution. He focused mainly on the representation of objects—often still lifes—in a style that combined classicism and cubism, with a certain cézannian influence. He worked in etching, where he demonstrated a great technical mastery, with which he achieved effects of a timeless, almost magical reality.[44] In Italy, it is worth mentioning the Gruppo Romano Incisori Artisti (Roman Group of Engraving Artists), which emerged in 1921 on the initiative of Federico Hermanin and brought together some twenty-five artists of diverse styles who exhibited collectively in various Italian art competitions.[45]

Russia and Suprematism[edit]

In Russia emerged around 1915 Suprematism, a style of abstract cut based on fundamental geometric shapes, especially the square and the circle, with a restricted chromatic range, especially black and white. One of its exponents was El Lissitzky, architect, painter, designer, photographer and typographer, creator of the proun ("Projects for the affirmation of the new"), a type of geometric abstract design intended as a synthesis between painting and architecture, which he developed in paintings, prints and drawings.[46]

Dada[edit]

The next of the new styles was dadaism, a movement of reaction to the disasters of World War I, which involved a radical approach to the concept of art, which loses any component based on logic and reason, and claims the doubt, chance, the absurdity of existence. This translated into a subversive language, where both the themes and the traditional techniques of art were questioned, experimenting with new materials and new forms of composition, such as collage, the photomontage and the readymade.[47] Among its representatives is Jean Arp, painter, sculptor and poet, one of the founders of the movement in Zürich. In 1916 he illustrated Tristan Tzara's 25 Poems and made the woodcut series Symmetry Studies, of abstract cut. Since then he continued to produce etchings and, above all, woodcuts, with a sober style in carving and sharp in ink, with images that move between abstraction and morphology. He also illustrated his own texts: Sailboat in the forest (1957), 1, rue Gabrielle (1958), Towards the infinite white (1960).[48] Also notable was Kurt Schwitters, who produced in 1923 a series of six lithographs of his work Merz, in a numbered edition of fifty copies. He elaborated it on papers of different colors, so it obtained a certain appearance of collage.[49] Another exponent was Christian Schad, a contributor to the magazine Sirius, for which he produced one woodcut per issue, and for whose publisher he created a booklet of ten woodcuts in 1915.[50]

Surrealism[edit]

Between the 1920s and 1940s, Surrealism developed, a movement that placed special emphasis on imagination, fantasy and the world of dreams, with a strong influence of psychoanalysis, with a figurative and an abstract tendency.[51] One of its greatest exponents was Salvador Dalí, who evolved from a formative phase in which he tried various styles (impressionism, futurism, cubism, fauvism) to a figurative surrealism strongly influenced by Freudian psychology.[52] In the graphic field he devoted himself preferably to book illustration, such as The Songs of Maldoror by Count of Lautréamont (1934), Don Quixote by Cervantes (1957) and Divine Comedy by Dante (1960). In 1957 he versioned Los caprichos by Goya. Also noteworthy is his Surrealist Tauromaquia, from 1976.[53]

Joan Miró practiced especially lithography, as he sought the result most similar to painting—it used to be said of him that he painted as he engraved and engraved as he painted -. Particularly noteworthy is his series Barcelona (1944), a graphic version of his pictorial series Constellations, a set of fifty lithographs in which he recreated his personal world, with generally abstract images in which human or animal figures are occasionally perceived, as well as some of his usual motifs such as stars and birds. The set stands out for its dramatic essence, motivated by the artist's pessimism in the face of war.[54] He also illustrated bibliophile books: Parler seul by Tristan Tzara (1948–1950), À toute épreuve by Paul Éluard (1958, Le miroir de l'homme par les bêtes by André Frénaud (1972), Oda a Joan Miró by Joan Brossa (1973).[55]

Other Surrealist artists who practiced printmaking were Paul Klee, Max Ernst, André Masson and Yves Tanguy. Klee started in the Jugendstil and was a member of the expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, before turning to surrealism. He recreated in his work a fantastic and ironic world, close to that of children or madmen. In his compositions he was especially interested in aspects such as color, light, time and movement. He worked mainly in lithography: Sommeil d'hiver (1938), Tête d'enfant (1939).[56] Ernst went through expressionism, Dadaism and surrealism, with an original work of strong personality. His first prints (1911–1912), in linocut, are related to the group Die Brücke. In his Dadaist stage he elaborated the lithographic series Fiat modes, pereat ars (1919), where he shows the influence of metaphysical Giorgio de Chirico. He later practiced other techniques such as collage, photomontage and frottage.[57] Of particular note is his novel-collage Une semaine de bonté (1933), engraved in woodcut, in a realistic style charged with humor and eroticism, with a certain Goyaesque influence.[58] Masson was initiated in cubism until leading to a surrealism marked by graphic automatism. He illustrated books such as Justine by Marquis de Sade (1928) and Martinique, enchantress of snakes by André Breton (1941), as well as various works by Mallarmé, Coleridge and Malraux.[59] Tanguy was characterized by a type of imagery in desert plains of infinite horizon and milky light populated by biomorphic beings, which he transferred to his graphic work.[60]

In England the sculptor Henry Moore, who was also a draftsman and engraver. In 1931 he produced the woodcut series Sculpted Figures. During the Second World War, when he was appointed War Artist, he made a series of drawings on shelters that he transferred to lithographs. In 1969 he made twenty-eight drypoints inspired by the skull of an elephant, from which he recreated imaginary caves, landscapes and architectures, denoting the influence of Piranesi.[61] Belatedly attached to surrealism, the Cuban Wifredo Lam made lithographs in which he fused this style with certain cubist tendencies.[62]

The interwar period saw the emergence in France of the so-called School of Paris, a heterodox group of artists linked to various artistic styles such as post-impressionism, expressionism, cubism and surrealism. The term encompasses a wide variety of artists, both French and foreign, who resided in the French capital in the interval between the two world wars.[63] In the graphic field, Russian-born Marc Chagall stood out, who developed a style denoting Fauvist and Cubist influences, although interpreted in a personal way, with a work of dreamlike tone and intense chromaticism. He began printmaking at the age of thirty-six, with the illustrations for Paul Cassirer's autobiography Mein Leben (1923), twenty-six etchings and drypoints. Already established in Paris, he carried out several commissions for the publisher Vollard: Les âmes mortes by Nikolai Gogol (1924–1925), Les Fables by La Fontaine (1926–1931), L'Ancien Testament (1931–1939). Exiled in the United States between 1941 and 1948, he produced here the lithographic series Four Tales from the Arabian Nights. Back in France, he produced several series of lithographs: Daphnis and Chloe (1961), Circus (1967), In the Land of the Gods (1967); as well as etchings, aquatints, monotypes and the woodcut series Poems (1968).[64] Also worth mentioning in this school are: Louis Jou, devoted himself to woodcuts intended for the illustration of books in luxury editions; André Dunoyer de Segonzac devoted himself to intaglio, in which he was a prolific author (1600 plates), his main work was the illustration of the Georgics of Virgil (1947); Luc-Albert Moreau excelled in lithography; in poster art, Paul Colin, Jean Carlou and Cassandre stood out, renewing and modernizing the genre.[65]

In the 1930s, the use of offset lithography for artistic printing began to become generalized. The pioneer was the French painter based in the United States Louis Henri Jean Charlot, who in 1933 published in Los Angeles his Picture book in thirty-two lithographs on zinc plate printed in offset. The printmaker was Lynton Kistler, who worked for many modern artists, and was joined by Albert Carman in New York. Shortly thereafter it came to the United Kingdom, where it was practiced by Barnett Freedman, Paul Nash and John Piper. These artists popularized the offset in the 1930s and 1940s, in unlimited print runs and at low cost, a fact that in turn produced a certain discredit of this technique, considered inferior in artistic quality to the artisanal techniques of traditional printmaking.[66]

In the United States, the work of John French Sloan, a painter and engraver of the Ashcan school, a realist style trend characterized by its urban genre scenes, is also noteworthy. He preferably painted scenes of everyday life in New York, focusing mainly on the objective description, without critical or moral evaluations, although sometimes with a certain dramatic component. A good example is his etching Windows at Night (1910).[67] To the same school belonged George Wesley Bellows, author of urban scenes of New York, with a preference for images of boxing and baseball. He devoted himself to lithography, a technique in which he illustrated several books, especially by H. G. Wells.[68] Edward Hopper was a representative of the so-called American Realism or American Scene, with urban scenes of anonymous and lonely characters. In his early days he worked as an illustrator to make ends meet, a period that includes his series of etchings Night Shadows (1921) and Train and bathers (1930).[69]

Spain[edit]

In the Spain of the first decades, apart from the work of great artists such as Picasso, Dalí and Miró, it is worth remembering: Carlos Verger, painter, poster artist and engraver, author of reproductions and original works, such as Beethoven, Carmen, Lavanderas and Foro Romano;[70] Ricardo Baroja practiced etching and aquatint with Goyaesque influence, author of landscapes and popular themes;[71] Francisco Iturrino, Fauvist style, focused on images of nudes, horses and gardens, with some influence of Regoyos;[72] Xavier Nogués, in the novecentista style, was a notable watercolorist, with a certain satirical and caricatured vein, with the illustration of El sombrero de tres picos by Pedro Antonio de Alarcón standing out among his works;[73] Daniel Vázquez Díaz, somewhere between realism and cubism, produced etchings and lithographs on World War I, as well as landscapes and social scenes;[74] José Gutiérrez-Solana, linked to expressionism, combined traditional and contemporary art, with a rough and dramatic style, focusing on sordid and gloomy themes inspired by España negra (popular characters, processions, bullfights);[75] Antoni Clavé was a painter, sculptor, engraver and set designer, and practiced lithography, etching and aquatint equally, generally in book illustration (Lettres d'Espagne by Prosper Mérimée, 1943; Candide by Voltaire, 1948; Gargantuaby François Rabelais, 1950).[76] In 1910 the Society of Spanish Engravers was founded. Some artists of this society created in 1928 the group Los Veinticuatro, which three years later was renamed Agrupación Española de Artistas Grabadores.

Post-war[edit]

After World War II, the historical avant-garde gave way to a new series of movements ranging from figurative to abstract art, from the most traditional art to action art or conceptual art. One of the first, in the immediate postwar period, was Informalism, a set of trends based on the expressiveness of the artist and the renunciation of any rational aspect of art (structure, composition, preconceived application of color). It was an eminently abstract style, where the material support of the work gained relevance, which took the leading role over any theme or composition. At the same time, in the United States we find abstract expressionism—also called action painting—an equally abstract style in which the artist's gestures stand out.[77]

Among his European exponents and within graphic art it is worth naming: Jean Dubuffet, an artist who combined abstraction with some biomorphic references and allusions to graffiti, as in his lithograph The Walls (1949);[78] Lucio Fontana, founder of spatialism, created a type of abstract images that he called "spatial concepts", characterized by their monochromatism and by the introduction of space in the image through tears and holes, which he also transferred to printmaking;[79] and Hans Hartung, creator of a graphic universe of abstract cut that he developed in a self-taught way, with a work that includes about two hundred plates in various techniques, especially intaglio and lithography.[80] In the United States it is worth mentioning: Jackson Pollock, creator of dripping or dripping paint on canvas, in generally abstract compositions, although he also produced figurative or partially figurative works in black and white (Untitled, 1945, etching);[44] Mark Rothko, of Russian origin, was noted for his rectangular formats, intense coloring and blurred contours, which he transferred to his graphic production;[81] Willem de Kooning was one of the few painters who introduced the human figure in his works, although immersed in abstract scenes and with fragmented forms, as if dislocated, in curvilinear, dynamic spaces, with a graphic work centered on etching and lithography, in compositions similar to his pictorial work.[82]

Antoni Tàpies, who created his own style in which tradition and innovation were combined in an abstract style full of symbolism that gave great relevance to the material substratum of the work. He started out in the group Dau al Set, some of whose members also practiced printmaking, such as Modest Cuixart, Joan Ponç and Joan-Josep Tharrats; between 1948 and 1956 the group published the magazine of the same name, which showed some of his works. Alone, Tàpies practiced printmaking in a secondary way to his painting, but he left works of great quality with diverse techniques: he practiced lithography, intaglio and serigraphy, as well as typographic stencils. His work includes the series Cataluña, in large silkscreen prints, as well as illustrations of books such as La nuit grandissante by Jacques Dupin (1967), Air by André Bouchet (1971) and La clau del foc by Pere Gimferrer (1973).[83]

Another exponent of Spanish informalism was Antonio Saura, one of the founders of the group El Paso (1957–1959), which also included Manolo Millares, Rafael Canogar, Luis Feito, Juana Francés, Manuel Rivera, Martín Chirino, Manuel Viola and the sculptor Pablo Serrano; all of them were creators of prints.[84] Saura was perhaps the most outstanding member, author of gestural, expressive works, of sober colors—preferably black and white—in images where he does not exclude figuration, some deformed figures resembling monsters.[85] It is also worth mentioning the Basque sculptor Eduardo Chillida, who was also a notable engraver, author of some two hundred prints -some of them murals- and book illustrations: Les chemins des devins suivi de menerbes by André Frénaud (1966), Meditation in Kastilien by Max Hölzer (1968), Die Kunst und der Raum by Martin Heidegger (1969), Más allá by Jorge Guillén (1973), Le sujet est la clairiere de son corps by Charles Racine (1975), Adoración by José Miguel Ullán (1977). Almost all his production revolves around the spatial reflection on the sculptural plane and volume.[86]

As a reaction to informalist abstraction, the so-called Neofiguration emerged, a movement that recovered figurative art, with a certain expressionist influence and total freedom of composition. Although they were based on figuration does not mean that this was realistic, but could be deformed or schematized to the taste of the artist.[87] Among its components are: Francis Bacon, creator of a universe centered on the human figure isolated or in small groups, generally deformed, in closed but undefined spaces, which he also transferred to prints;[88] Bernard Buffet illustrated several publications, such as The Songs of Maldororor by Count of Lautréamont (1952), The Passion of Christ (1954), Jean Cocteau's Human Voice (1957), Cyrano de Bergerac's Les Voyages Fantastiques (1958) or Dante's The Inferno (1976);[89] Lucian Freud specialized in portraits and nudes, with a stark realism, generally working in etching, a technique that allowed him to develop his draftsman qualities optimally (A Couple, Woman's Head, The Painter's Mother, Beautiful);[90] the chilean Roberto Matta also excelled in illustration: The Songs of Maldoror by Lautréamont (1938), The Word is Péret's by Benjamin Péret (1941), Arcanum 17 by André Breton (1945), Employment of Time by Michel Butor (1956), Watchtowers on White by Henri Michaux (1959).[91] The members of the CoBrA group (Karel Appel, Asger Jorn, Corneille, Pierre Alechinsky, Constant Nieuwenhuys) also practiced printmaking, especially lithography, in works notable for their thick strokes and vivid colors.[92]

From 1950, kinetic art (also called op-art, "optical art") developed, a style that emphasized the visual aspect of art, especially optical effects, which were produced either by optical illusions (ambiguous figures, lingering images, moiré pattern effect), or through movement or plays of light. It was an abstract but rational, compositional style, unlike Informalism.[93] Notable among its members were Victor Vasarely and Eusebio Sempere. Vasarely worked in his beginnings as a graphic designer for advertising agencies. Later he produced a remarkable graphic work in which he recreated his kinetic universe, based on optical effects. He worked mainly in silkscreen: Chell (1949), Album Vasarely (1958), Album III (1959), Constellations (1967).[94] Sempere focused his work on studies of light and optical vibrations, sometimes starting from landscapes or figurative elements that he converted into abstractions of intense lyricism. In 1969 he made a series of serigraphs on poems by Góngora.[95]

An unclassifiable artist who began to be successful in the 1950s was M. C. Escher, who created a fantastic work where he recreated imaginary worlds and impossible objects. He practiced woodcut, lithography and mezzotint, with some four hundred originals of which dozens, hundreds or thousands of reproductions were made, depending on the work. His images combine geometric and mathematical concepts, as well as figures of fantastic animals and other products of his imagination.[96]

Between the 1960s and 1970s there was a revaluation of lithography, especially in the United States. Influenced by Picasso's unorthodox use of this technique between 1945 and 1950, in which he drew and scratched on stone, many artists worked lithography with unconventional methods. In 1960, June Wayne founded in Los Angeles the Tamarind Lithography Workshop, which profoundly marked the American graphic production of those decades. Other companies followed, such as Universal Limited Art Editions (ULAE) and Gemini GEL. Many artists worked with those companies, such as Josef Albers, Jasper Johns, Robert Rauschenberg, Robert Motherwell, Elaine de Kooning, Richard Diebenkorn, Jim Dine, Gego, Mel Ramos, Edward Ruscha, Sam Francis, Rufino Tamayo, Louise Nevelson, Philip Guston, etc.[97]

In those years, pop art developed in the United States, a style with a marked component of popular inspiration that took images from the world of advertising, photography, comics and the mass media.[98] One of its main exponents was Andy Warhol. He used to work by silkscreen, in series ranging from portraits of famous people such as Elvis Presley, Marilyn Monroe, Jacqueline Kennedy or Mao Tse-tung, through his gruesome Catastrophes series, Electric Chairs and Race Riots, to all kinds of objects, such as his series of Campbell's Soup Cans or Coca-Cola, elaborated with a garish, strident colorism and a pure, impersonal technique.[99] Warhol chose his images from the mass media, stereotypical images, which he cut out and framed to send to the silkscreen workshop, where they were enlarged, the format and color chosen and the print run made, on paper or canvas, in unnumbered series. His work is cold, indifferent, uniform and mechanized, suitable for an industrialized society geared towards consumption. Even death is treated in the same distant and cold way, as it is still a common image in the media.[100] Another American exponent was Roy Lichtenstein, who was inspired by comics, with images in vignettes that often show the stippling typical of printed editions. These are trivial, almost vulgar images, but emphasized in such a way as to convey the emotions of the characters, albeit with a cold and mechanical look.[101]

Pop art also appeared in the United Kingdom, where Richard Hamilton and David Hockney stood out. Hamilton elaborated images based on popular culture, influenced by advertising, to which he gave a critical character. He generally worked in mixed media, such as his Figurine (1969–1970), a lithographic photo-fset with silkscreen in collage, stencil and cosmetics.[102] Hockney moved away in his work from the popular and commercial aspect of his contemporaries, with images of interior evocation and fantastic component, poetic and ironic allusions, and with certain references to caricature and the picturesque.[101]

In Spain, a realist reaction arose in the 1960s in the face of the informalist current, which had as its exponent the group Estampa Popular, founded in 1958 in Madrid by José García Ortega, along with the outstanding Agustín Ibarrola and Ricardo Zamorano. Influenced by pop art and French New Realism, their style is realistic, in simple images, of clear and simple composition, marked by their political commitment anti-Francoist.[103] A split from the previous one was the Equipo Crónica, founded in 1964 in Valencia by Manolo Valdés, Rafael Solbes and Juan Antonio Toledo, with a realistic style influenced by pop art and mass media.[104] Other Spanish artists of these years who practiced printmaking were: Luis Gordillo, Juan Genovés, Joan Hernández Pijuan, Albert Ràfols Casamada, Josep Maria Subirachs, Eduardo Arroyo, José Hernández and Javier Mariscal.[105]

The 1960s saw the emergence of post-painterly abstraction, an abstracting movement that led shortly afterwards to minimalism, with works of marked simplicity, reduced to a minimal motif.[106] One of its exponents was Frank Stella, author of images of flat design centered on geometric figures, in whose printed version he used to employ metallic and fluorescent inks (Star of Persia I, 1967).[107]

As a reaction to the previous one, hyperrealism emerged simultaneously, a style characterized by its superlative and exaggerated vision of reality, which is captured with great accuracy in all its details, with an almost photographic aspect.[108] One of its most prominent representatives was Chuck Close. In his Self-Portrait/White Ink (1978), he produced in etching and aquatint a photographic-looking self-portrait of himself made from a gridded grid, in which he worked out each grid in isolation based on the tones of the aquatint.[109] In Spain, it is worth mentioning Antonio López García, who developed a work of an almost photographic realism not without a certain lyricism and evocations of surrealist tone.[110] He mainly practiced lithography (Rosa y Membrillo, 1992).[111]

Also in the 1960s emerged the so-called action art, various trends based on the act of artistic creation, where the important thing is not the work itself, but the creative process, in which in addition to the artist often involves the public, with a large component of improvisation. It encompasses various artistic manifestations such as happening, performance, environment or installation.[112] Although by its nature it did not have much reflection in graphic art, some of its exponents practiced printmaking, such as Joseph Beuys, a multifaceted German artist who was a painter, sculptor, teacher and art theorist. He practiced etching, aquatint and lithography: Schwurhand: Kalb mit Kinder (1980), Schwurhand: Zelt und Lichtstrahl (1980), Zirkulationszeit: Meerengel 2 Robben (1982), Tränen: Frauentoroso (1985).[113]

From the middle of that decade the conceptual art tendencies were appearing, focused on the dematerialization of art. It includes trends such as arte povera, body art and land art, as well as feminist art and various other manifestations.[114] By its nature, this current did not work especially in prints, but some of its artists used it to disseminate their works, such as the Bulgarian Christo, author of environmental installations, many of which consisted of wrapping objects or monuments. In his graphic work he used mixed techniques, such as Wrapped Monument of Vittorio Emanuele (1975), where he used lithography and a collage of fabric, photography, twine, staples and tape.[115]

During the student protests of May '68, the Atelier Populaire (popular workshop) emerged within the Paris School of Fine Arts, a group of students who were in charge of the elaboration of propaganda posters for their actions, which they placed all over the city. They designed some three hundred and fifty posters, most of them made in silkscreen printing, which stood out for their visual impact and the strength of their slogans, and became emblematic of the protests.[116]

Since 1975, the art proper to postmodernism or postmodern art developed as opposed to the so-called modern art. These artists assumed the failure of the avant-garde movements as the failure of the modern project: the avant-garde intended to eliminate the distance between art and life, to universalize art; the postmodern artist, on the other hand, is self-referential, art talks about art, they do not intend to do social work.[117] One of its exponents with achievements in graphic art is Eric Fischl, an American artist of realist style with a strong expressive character, influenced by Max Beckmann, Lucian Freud or Edward Hopper. His subject matter focused mainly on sexuality, with abundant representations of naked bodies, in erotic attitudes, but with a certain enigmatic, anguished, oppressive air, which is emphasized by his muted, grayish chromatic range, with a lighting of strange intensity that accentuates the expressive style of his works.[118] The Spaniard Miquel Barceló has developed a versatile oeuvre in which multiple influences can be perceived -among which African art stands out-, with the use of diverse artistic techniques and procedures, from painting, sculpture and prints to ceramics and casting. He has worked with etching, aquatint, drypoint, lithography and serigraphy, in individual works (Suite Tres Caprichos, 1988) or in book illustrations, such as Divine Comedy by Dante or La música callada del toreo by José Bergamín (2015).[119][120]

Within postmodern art there were several movements such as the Italian transvavantgarde or German neoexpressionism. In the former, it is worth mentioning Francesco Clemente, painter and poet, influenced in his work by Cy Twombly and Indian art. In both his paintings and prints he combines abstraction with figuration.[121] In the second are artists such as Georg Baselitz, Sigmar Polke and A. R. Penck. Baselitz is a painter, sculptor and printmaker, with an oeuvre focused on overcoming the contrast between figurative and abstract painting. One of his hallmarks is the inversion of the images, which are seen upside down, with bright and intense colors.[122] Polke was a painter and printmaker, influenced in his work by pop art, with a style that mixes modern painting with elements taken from advertising and mass media, with a certain tendency to kitsch.[123] Penck is a painter, sculptor and graphic artist, influenced by primitive art he developed a style of totemic appearance, in which one can also glimpse influences of Paul Klee and Jackson Pollock.[124]

In 1992, the International Olympic Committee celebrated the centenary of its founding by publishing a graphic work titled Olympic Centennial Suite, a set of fifty lithographs produced by various artists from around the world, including: Eduardo Chillida, Luis Gordillo, Antoni Tàpies, Sol LeWitt, Antonio López, Arman, César, Jiří Georg Dokoupil, Nam June Paik, Erró, Dennis Oppenheim, Mimmo Paladino, Corneille, Jean Tinguely, Wolf Vostell, Jesús Rafael Soto and other representatives of the art scene of the time.[125]

In the last decades of the century, the computer revolution led to the emergence of a new technique, digital printing, in which the graphic design is done by computer. This new modality has been criticized because it is almost entirely based on computer technology and has therefore lost the artisanal component of traditional printmaking. However, its advocates emphasize the creative act, the original design that marks the artist's work. Be that as it may, over the years digital printmaking has been accepted by the art world in general, and many artists now use this technique, either alone or in hybrid form with other graphic procedures. Also, many galleries and institutions already have digital creations among their funds and collections. In 1998, the Calcografía Nacional de España held an exhibition entitled La Estampa Digital, where it showed some of the main novelties of this technique.[126]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, pp. 757–758)

- ^ Morant (1980, p. 456)

- ^ "Impresión Offset – La magia de la impresión profesional".[permanent dead link]

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 86–90)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 103–106)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 112–113)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 106)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 113)

- ^ Cassou (1976, pp. 236–242)

- ^ Cassou (1976, pp. 242–244)

- ^ Cassou (1976, pp. 245–248)

- ^ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, pp. 776–777)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 266)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 865)

- ^ "Cronología biográfica". Archived from the original on 5 October 2018. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 1283–1284)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 2074)

- ^ Dempsey (2002, pp. 66–69)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 144)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 505)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 539)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 2078)

- ^ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, pp. 325–327)

- ^ Dube (1997, p. 31)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, pp. 16–19)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1065)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, pp. 29–30)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, pp. 34–38)

- ^ Becks-Malorny (2007, pp. 14–140)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 147–148)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1280)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 153)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1077)

- ^ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, pp. 702–703)

- ^ a b Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 146)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 868)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 177)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 168)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 623)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 42)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1817)

- ^ "Historia de la Bauhaus".

- ^ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, p. 784)

- ^ a b Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 151)

- ^ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 161)

- ^ "El Lissitzky, la expresión total al servicio del arte y la revolución".

- ^ Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (1991, p. 253)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 99)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 148)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1810)

- ^ Azcárate Ristori, Pérez Sánchez & Ramírez Domínguez (1983, pp. 830–831)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 478)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 122–123)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 123)

- ^ Gallego (1999, p. 472)

- ^ "Paul Klee". Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 571)

- ^ "LA BOUE, L´EAU, LE FEU, LE SANG, LE NOIR, LA VUE, INNCONNU…".

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1302)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1927)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1375)

- ^ "Wifredo Lam".

- ^ Historia del arte 26. Vanguardias artísticas I (1991, pp. 53–55)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 447)

- ^ Historia del arte 26. Vanguardias artísticas I (1991, pp. 75–76)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 119)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 151–152)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 188–189)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 944)

- ^ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 334)

- ^ Esteve Botey (1935, p. 337)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 158–159)

- ^ Gallego (1999, pp. 432–433)

- ^ Gallego (1999, p. 444)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 880–881)

- ^ Gallego (1999, pp. 475–476)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 5–7)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 152–153)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 153)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 896)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 1609–1610)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 152)

- ^ Gallego (1999, p. 479)

- ^ Gallego (1999, p. 491)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, p. 64)

- ^ Gallego (1999, p. 514)

- ^ González (1991, pp. 17–20)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, pp. 133–134)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 288)

- ^ "Lucian Freud, el pintor que graba".

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1308)

- ^ "Appel, CoBrA y el Grabado".

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 22–25)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 2030)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1831)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 153–154)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 120–121)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 10–15)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 10–17)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, p. 96)

- ^ a b Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 156)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 155–156)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, pp. 126–127)

- ^ García Felguera (1993, pp. 120–121)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 127)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 26–29)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 157)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 30–32)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 157)

- ^ Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (1988, p. 1188)

- ^ "Antonio López". Archived from the original on 27 January 2021. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ González (1991, pp. 35–38)

- ^ "Joseph Beuys". Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ González (1991, pp. 31–34)

- ^ Carrete & Vega (1993, p. 157)

- ^ Dempsey (2002, p. 289)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, pp. 33–41)

- ^ Cirlot (1990, p. 41)

- ^ "Miquel Barceló". Archived from the original on 21 February 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Miquel Barceló en su papel gráfico". 20 November 2015.

- ^ "Francesco Clemente".

- ^ "Georg Baselitz". Archived from the original on 17 January 2020. Retrieved 2 November 2022.

- ^ "Sigmar Polke".

- ^ "A. R. Penck".

- ^ "Suite Olympic Centennial".

- ^ "La estampa digital". 13 January 2010.

References[edit]

- Azcárate Ristori, José María de; Pérez Sánchez, Alfonso Emilio; Ramírez Domínguez, Juan Antonio (1983). Historia del Arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Anaya. ISBN 84-207-1408-9.

- Becks-Malorny, Ulrike (2007). Kandinsky. Köln: Taschen. ISBN -978-3-8228-3539-5.

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo M.; Esteban Lorente, Juan Francisco; Álvaro Zamora, Isabel (2010). Introducción general al arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 978-84-7090-107-2.

- Historia del grabado, ESTEVE BOTEY, Francisco, Barcelona, Labor, 1935

- Carrete, Juan; Checa, Fernando; Bozal, Valeriano (2001). Summa Artis XXXI. El grabado en España (siglos XV-XVIII) (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-239-5273-8.

- Carrete, Juan; Vega, Jesusa (1993). Grabado y creación gráfica (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Cassou, Jean (1976). Picasso (in Spanish). Barcelona: Círculo de Lectores. ISBN 84-226-0868-5.

- Chilvers, Ian (2007). Diccionario de arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza Editorial. ISBN 978-84-206-6170-4.

- Cirlot, Lourdes (1990). Las últimas tendencias pictóricas (in Spanish). Barcelona: Vicens-Vives. ISBN 84-316-2726-3.

- de la Plaza Escudero, Lorenzo; Morales Gómez, Adoración (2015). Diccionario visual de términos de arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 978-84-376-3441-8.

- Dempsey, Amy (2002). Estilos, escuelas y movimientos (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-89396-86-8.

- Diccionario enciclopédico Larousse (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta. 1990. ISBN 84-320-6070-4.

- Diccionario Larousse de la Pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta-Agostini. 1988. ISBN 84-395-0976-6.

- Dube, Wolf-Dieter (1997). Los Expresionistas (in Spanish). Barcelona: Destino. ISBN 84-233-2909-7.

- Enciclopedia del Arte Garzanti (in Spanish). Madrid: Ediciones B. 1991. ISBN 84-406-2261-9.

- Esteve Botey, Francisco (1935). Historia del grabado (in Spanish). Barcelona: Labor.

- Fahr-Becker, Gabriele (2008). El modernismo. Potsdam: Ullmann. ISBN 978-3-8331-6377-7.

- Fatás, Guillermo; Borrás, Gonzalo M. (1990). Diccionario de términos de arte y elementos de arqueología, heráldica y numismática (in Spanish). Madrid: Alianza. ISBN 84-206-0292-2.

- Fernández Polanco, Aurora (1989). Fin de siglo: Simbolismo y Art Nouveau (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Gallego, Antonio (1999). Historia del grabado en España (in Spanish). Madrid: Cátedra. ISBN 84-376-0209-2.

- García Felguera, María Santos (1993). El arte después de Auschwitz (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- García Felguera, María Santos (1993). Las vanguardias históricas (y 2) (in Spanish). Madrid: Historia 16.

- Gibson, Michael (2006). El simbolismo. Colonia: Taschen. ISBN 978-3-8228-5030-5.

- González, Antonio Manuel (1991). Las claves del arte. Últimas tendencias (in Spanish). Barcelona: Planeta. ISBN 84-320-9702-0.

- Gutiérrez, Fernando G. (1967). Summa Artis XXI. El arte del Japón (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Hofstätter, Hans H. (1981). Historia de la pintura modernista europea (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-7031-286-3.

- Honour, Hugh; Fleming, John (2002). Historia mundial del arte (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 84-460-2092-0.

- Laneyrie-Dagen, Nadeije (2019). Leer la pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Larousse. ISBN 978-84-17720-32-2.

- Lucie-Smith, Edward (1991). El arte simbolista (in Spanish). Barcelona: Destino. ISBN 84-233-2032-4.

- Morant, Henry de (1980). Historia de las artes decorativas (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe. ISBN 84-239-5267-3.

- Rivière, Jean Roger (1966). Summa Artis XX. El arte de la China (in Spanish). Madrid: Espasa Calpe.

- Souriau, Étienne (1998). Diccionario Akal de Estética (in Spanish). Madrid: Akal. ISBN 84-460-0832-7.

- Sturgis, Alexander; Clayson, Hollis (2002). Entender la pintura (in Spanish). Barcelona: Blume. ISBN 84-8076-410-4.

- Historia del arte 26. Vanguardias artísticas I (in Spanish). Barcelona: Salvat. 1991. ISBN 84-345-5361-9.