Eureka Stockade (fortification)

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Eureka Rebellion |

|---|

|

|

|

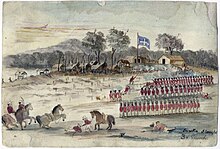

The Eureka Stockade was a crude battlement built and garrisoned by rebel gold miners at Ballarat in Australia during the Eureka Rebellion of 1854. It stood from 30 November until the Battle of the Eureka Stockade on 3 December. The exact dimensions and location of the stockade are a matter of debate among scholars. There are various contemporary representations of the Eureka Stockade, including the 1855 trial map and Eureka Slaughter by Charles Doudiet.

Fortification of the Eureka lead[edit]

After the oath swearing ceremony where Peter Lalor mounted the stump and called for liberty and the formation of paramilitary companies, about 1,000 rebels marched in double file from Bakery Hill to the Eureka lead behind the Eureka Flag being carried by Henry Ross, where construction of the stockade took place between 30 November and 2 December.[1][2] The stockade itself was a ramshackle affair described in Raffaello Carboni's 1855 memoirs as "higgledy piggledy."[3] There were existing mines within the stockade,[4] and it consisted of diagonal wooden spikes made from materials including pit props and overturned horse carts.

According to Lalor, the stockade "was nothing more than an enclosure to keep our own men together, and was never erected with an eye to military defence."[5] However, Peter FitzSimons asserts that Lalor may have downplayed the fact that the Eureka Stockade may have been intended as something of a fortress at a time when "it was very much in his interests" to do so.[6] The construction work was overseen by Frederick Vern, who had apparently received instruction in military methods. John Lynch wrote that his "military learning comprehended the whole system of warfare ... fortification was his strong point."[7] Les Blake has noted how other descriptions of the stockade "rather contradicted" Lalor's recollection of it being a simple fence after the fall of the stockade.[8] Testimony was heard at the high treason trials for the Eureka rebels that the stockade was four to seven feet high in places and was unable to be negotiated on horseback without being reduced.[9]

The location of the stockade has been described as "appalling from a defensive point of view," as it was situated on "a gentle slope, which exposed a sizeable portion of its interior to fire from nearby high ground."[10][note 1] A detachment of 800 men, which included "two field pieces and two howitzers" under the commander in chief of the British forces in Australia, Major General Sir Robert Nickle, who had also seen action during the 1798 Irish rebellion, would arrive after the insurgency had been put down.[12][13] In 1860, Withers stated in a lecture that "The site was most injudicious for any purpose of defence as it was easily commanded from adjacent spots, and the ease with which the place could be taken was apparent to the most unprofessional eye."[14]

Debate over the exact dimensions and location of the Eureka Stockade[edit]

As the materials used by the rebels to fortify the Eureka lead were quickly removed and the landscape subsequently altered by mining, the exact location of the Eureka Stockade is unknown.[15] Various studies have been undertaken that have arrived at different conclusions. Jack Harvey (1994) has conducted an exhaustive survey and has concluded that the Eureka Stockade Memorial is situated within the confines of the historical Eureka Stockade.[16][17]

It encompassed an area said to be one acre; however, that is difficult to reconcile with other estimates that have the dimensions of the stockade as being around 100 feet (30 m) x 200 feet (61 m).[18] Contemporaneous descriptions and representations vary and have the stockade as either rectangular or semi-circular.[19] Harvey believes the existing evidence points to a semi-circular stockade that occupied an area of three acres.[20]

High Treason trial witnesses and map[edit]

Three witnesses in the 1855 Victorian High Treason trials were questioned about the size and shape of the stockade.

Sub-inspector C. J. Carter testified, "It formed a parallelogram...I should think it was about 100 yards wide and double that length," or about four acres. Lieutenant T. B. Richards and Police Magistrate C. P. Hackett could not say if the stockade's perimeters met at a specific angle. Still, they both had the impression of sides, not the curved perimeter, in Huyghue's plan.[21]

Others were asked whether the stockade was fully enclosed or open at one corner, as seen in the trial exhibit. Goodenough and Carter believed it was fully enclosed. G. A. Amos stated:

"The slabs...were three or four foot separated in some places by other slabs placed crosswise, in some places by carts, and in some places by mounds of earth ... The portion which was open there was slightly defended by several mounds of earth. The earth taken out of the holes formed several mounds..."[22]

The only known contemporary map showing the stockade's geographical location was exhibited at the trials. It was prepared before the first trial in February 1855. Based on W. S. Urquhart's 1852 survey, the map reveals that the stockade was erected on the edge of "Urquhart's diggings," more commonly referred to as the gravel pits. It contains the dated signatures of Redmond Barry (four times), and on the reserve side, there is a cartoon figure and the words "one of the volunteers" and William a Beckett's initials "W.A.B." At the trials, Amos, Webster, Langley, Hackett and Richards all agreed that the map exhibit was generally true and correct. It features the route of the besieging forces, and two of the aforementioned witnesses have used a pencil to make relevant points. Commissioner Amos wrote "Bakery" for Bakery Hill and "E" for the police outpost, which Captain Thomas estimated to be 440 yards from the stockade. The camp in the trial map is 428 yards from the stockade. Another witness has made two notations concerning the arrest of Timothy Hayes near the stockade after the battle. The artist shows the Eureka Stockade built over a track. Government surveyor Thomas Burr, draftsman James Gaunt, and Eugene Bellairs, whose party was fired upon from the area a couple of days prior, all knew the location of the stockade but were not examined as to the fidelity of the trial map when called as witnesses. Concerning the trial map Attorney General William Stalwell told the jury in the trial of John Joseph that:

A plan has been prepared to enable you to understand the description more accurately. This stockade encompassed three sides of a parallelogram, leaving one end completely open, and it enclosed a number of tents; some of those tents were vacated at once, but in others some of the men remained, some of them sympathising with those men...[23]

MacFarlane notes that the defence counsels never directly called the accuracy of the trial map into question. However, they did request that "stricter evidence of its accuracy should be given by the survey officer who made it."[24]

Other eyewitness accounts[edit]

In his 1885 memoirs Raffaello Carboni said the stockade was "simply fenced in by a few slabs placed at random"[25] and that:

"Vern had enlarged the stockade across the Melbourne road and down the Warrenheip Gully...an acre of ground on the surface of a hill...The shepherd's holes inside the lower part of the stockade had been turned into rifle pits."[26]

Samuel Huyghue recalled that "the irregular enclosure of the Stockade comprised about an acre" and that "this rude barricade was continued between the mounds of earth thrown up in mining, the open spaces separating the 'claims' being thus filled up and rendered defensible."

Charles Evans' diary says it was "between one and two hundred yards in circumference..." Harvey notes that a circle of 100 yards circumference would have an area of only one-sixth of an acre and that Evan's might be referring to its diameter instead.[27]

Henry Powell, a miner from Creswick Creek, in a deposition stated that he "Looked in the ring," which appears to imply a circular perimeter.[27]

Other contemporary representations[edit]

There are two known drawings of the battle dating from 1854. Charles Doudiet was an associate of Henry Ross and aided the wounded rebel, noting his death at the Free Trade Hotel two days later in his sketchbook. He was present at the burning of Bentley's Hotel, the oath swearing ceremony on Bakery Hill and may have been an eyewitness to the early morning battle. Doudiet depicted these scenes from Eureka Rebellion, among others from the travels in Australia and time in Ballarat. His sketchbook, now under preservation at the Art Gallery of Ballarat, includes Eureka Slaughter, which has the stockade as a ring of defences.[28]

J.B Henderson's 1854 Eureka Stockade Riot was drawn by an eyewitness to the aftermath. It features the clash between the forlorn hope and the rebel garrison at the perimeter of the stockade.[29]

Also in the collection of the Art Gallery of Ballarat is Eureka Stockade by Samuel Huyghue, completed in 1882. Huyghue was an eyewitness to the Eureka Rebellion and was employed as a government clerk.[30]

See also[edit]

- Alamo Mission, site of a celebrated siege during the Texas Revolution in 1836

Notes[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. xiii, 196.

- ^ Carboni 1855, p. 59.

- ^ Carboni 1855, pp. 77, 81.

- ^ Blake 1979, p. 76.

- ^ Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement 1965, p. 37.

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, note 13.

- ^ Lynch 1940, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Blake 1979, pp. 74, 76.

- ^ The Queen v Joseph and others, 29 (Supreme Court of Victoria 1855).

- ^ Blake 2012, p. 88.

- ^ Harvey 1994, p. 91.

- ^ Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham 1978, p. 7.

- ^ Blake 1979, p. 93.

- ^ Harvey 1994, p. 24.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 190.

- ^ Harvey 1994.

- ^ Harvey, J.T., 'Locating the Eureka Stockade: Use of Geographical Information Systems (GIS) in a Historiographical Research Context: Computers and the Humanities', Vol. 37, No. 2, May 2003.

- ^ FitzSimons 2012, p. 648, note 12.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 190–191.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 257.

- ^ Harvey 1994, p. 87.

- ^ Harvey 1994, pp. 88–89.

- ^ MacFarlane 1995, p. 167-168.

- ^ MacFarlane 1995, p. 180.

- ^ Carboni 1855, p. 80.

- ^ Carboni 1855, pp. 80, 96.

- ^ a b Harvey 1994, p. 88.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, pp. 156–157.

- ^ Corfield, Wickham & Gervasoni 2004, p. 265.

- ^ Harvey 1994, pp. 39–40.

Bibliography[edit]

- Blake, Gregory (2012). Eureka Stockade: A ferocious and bloody battle. Newport: Big Sky Publishing. ISBN 978-1-92-213204-8.

- Blake, Les (1979). Peter Lalor: the man from Eureka. Belmont: Neptune Press. ISBN 978-0-90-913140-1.

- Carboni, Raffaello (1855). The Eureka Stockade: The Consequence of Some Pirates Wanting on Quarterdeck a Rebellion. Melbourne: J. P. Atkinson and Co. – via Project Gutenberg.

- Corfield, Justin; Wickham, Dorothy; Gervasoni, Clare (2004). The Eureka Encyclopedia. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Services. ISBN 978-1-87-647861-2.

- FitzSimons, Peter (2012). Eureka: The Unfinished Revolution. Sydney: Random House Australia. ISBN 978-1-74-275525-0.

- Harvey, Jack (1994). Eureka Rediscovered: In search of the site of the historic stockade. Ballarat: University of Ballarat. ISBN 978-0-90-802664-7.

- Hotham, Charles (1978). Three Despatches From Sir Charles Hotham. Melbourne: Public Record Office. ISBN 978-0-72-411706-2.

- Historical Studies: Eureka Supplement (2nd ed.). Melbourne: Melbourne University Press. 1965.

- Lynch, John (1940). Story of the Eureka Stockade: Epic Days of the Early Fifties at Ballarat (Reprint ed.). Melbourne: Australian Catholic Truth Society.

- MacFarlane, Ian (1995). Eureka from the Official Records. Melbourne: Public Record Office Victoria. ISBN 978-0-73-066011-8.

- Withers, William (1999). History of Ballarat and Some Ballarat Reminiscences. Ballarat: Ballarat Heritage Service. ISBN 978-1-87-647878-0.