Emin Arslan

Emir Emin Arslan | |

|---|---|

أمين مجيد أرسلان | |

| |

| Born | 13 July 1868 |

| Died | 9 January 1943 (aged 74) |

| Burial place | La Chacarita cemetery |

| Nationality | Ottoman, Argentine |

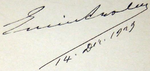

| Signature | |

| |

Emin Arslan (13 July 1868 – 9 January 1943) was a Lebanese author, journalist, editor and consul. He was the Consul General of the Ottoman Empire in Bordeaux, Brussels, Paris and Buenos Aires. He authored books and articles in Arabic, Spanish and French.

He initially supported the ideas of the Young Turks, who favoured a reform so as to restore the Ottoman constitution of 1876 and the parliament and grant rights to all the individuals and nations of the Empire. In 1914, while at office as Ottoman Consul General in Buenos Aires, he broke with the Young Turks government due to its alliance with the German Empire and its entrance in World War I, which Arslan harshly criticized.

He denounced the extermination of Armenians from the review he founded and edited, La Nota, in August 1915. During his stay in Europe he had also condemned the Hamidian massacres from the French press.[1]

After the war Arslan initially supported a provisional Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon. As the Mandate prolonged he denounced it as a corrupt and despotic colonization and adhered to the idea of the independence of former Ottoman Syria as a single sovereign state.[citation needed]

Early years and family[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (August 2017) |

Emin Arslan was born in Choueifat, Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate, Ottoman Empire. He belonged to a distinguished Druze family whose members hold traditionally the title of Emirs until today.

Emin was son of Zahiyya Shihāb and Mağīd Arslān, son of Milḥam, son of Ḥaidar, son of 'Abbās, son of Fakhreddīn.[2][3] He had three brothers: Nouhad, Fouad, Sa'īd and Tawfīq (also transliterated as Toufic). The latter helped found Greater Lebanon in 1920 and fathered Mağīd Arslān II (1908–1983), a Lebanon's independence hero, member of the Lebanese Parliament and government minister. Current traditional chief of the Arslān family, Talal Arslan, is therefore a great nephew of Emin Arslan.

Emin did not marry and had no children; he was succeeded by his nieces Rafīq Sa'īd Arslān, Malik Sa'īd Arslān, Zahiyya Tawfīq Arslān, Majīd Tawfīq Arslān (i.e. Mağīd Arslān II) and Nuhād Tawfīq Arslān.[4]

Political career in Mount Lebanon[edit]

In 1892 he was designated mudīr ('director') of the Far West Directorate (Nāḥyat al-Ġarb al-Aqṣā), in the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate. He resigned in 1893 after a conflict with the mutaṣarrif Na'ūm Pāšā (Naum Pasha). Arslan joined the Freemasonry on 24 August 1889.[5]

Exile in France[edit]

In 1893, he resigned as mudīr [clarification needed] and joined his friend Salim Sarkis in exile. They stopped briefly in Egypt and then went to Paris where, along with other Arab expatriates founded the "Turkish Syrian Committee."[6]

They contacted Ahmed Rıza, a major supporter of the Young Turks movement and editor of Meşveret, a Turkish written political newspaper. The main activity of the exiles was to spread criticism against the Ottoman regime through the general European press and from some party organs. They demanded restoration of the 1876 Ottoman constitution, reestablishment of the parliament and equal rights for individuals and communities.

"Kashf an-Niqāb" newspaper[edit]

Kashf an-Niqāb (كشف النقاب), i.e. "unveiling", was an Arabic written newspaper edited in Paris by Emin Arslan and his friend, writer and journalist Salim Sarkis, from 9 August 1894 until 25 July 1895.[7][8]

According to Sarkis, the Ottoman embassy pressured the French authorities into censoring the magazine and order the concierge to disclose names of visitors.[9]

"Turkiyā al-Fatāt" newspaper[edit]

"Turkiyā al-Fatāt (تركيا الفتاة) – La Jeune Turquie", i.e. "Young Turkey", was a bilingual biweekly edited in Paris in Arabic and French from December 1895 through middle 1897 by Emin Arslan and Ḫalīl Ġānim (خليل غانم) on behalf of the "Turkish Syrian Committee,"[10] self described as "journal of political propaganda." It criticized sultan Abdul Hamid II's government.

Co-editor Khalil Ghanem (Beirut 1847 – Paris 1903) had taken part in the previous reformist movement known as the Young Ottomans. Member of the first Ottoman parliament in 1877, the French Embassy in Constantinople (now Istanbul) granted him political asylum after his mentor Midhat Pasha was deposed.[6] Before meeting Arslan he had founded and edited al-Bassir (al-Bașīr البصير) weekly (Paris, 1881–1882).[11] Ghanem wrote also for the Journal des débats and was named chevalier of the French Legion of Honour in 1879.[12]

In Paris press[edit]

In 1896 Arslan wrote four articles that were published on La Revue Blanche, titled "Les Affaires de Crète", "Les Affaires d'Orient", "Les Troubles de Syrie" and "Les Arménians à Constantinople".[13] The latter was about the Occupation of the Ottoman Bank by Armenian militants and denounced the subsequent brutal retaliation. At those times Arslan frequented French writer Jules Claretie and they assisted together at the fourth International Press Congress in Stockholm in 1897.[14][15]

"Truce" with the Sultan's envoy[edit]

The Ottoman leadership tried to neutralize the exiles' propaganda in Europe. Despite not being too numerous, the exiles managed to get attention in the press. As one of them wrote: "(...) [the sultan] knows that if we are allowed a free hand in Paris our members and papers can do him more harm than ten French men-of-war."[9]

On 29 January 1897, one of their communiques was published by the Official Bulletin of the Kingdom of Italy. It was addressed to "the six powers signatories of the Treatises of Paris and Berlin" and it was signed by "Murād Bey, general deputy of the Young Turkey; Ḫalīl Ġānim, former representative of Syria before the Turkish parliament; Ahmed Rıza Bey; the Emir Emin Arslan; H. Anthony Salmoné", et al., on behalf of the "party of the general reformation in Turkey."[16]

The Ottoman government sent to Paris Ahmed Cemâluddîn with the mission of contacting the opposition and offer a general pardon for political prisoners, restoring the exiles in their former positions and reestablishing the constitution, in exchange for ending their propaganda campaign.[17]

Arslan states in his memories that initially he rejected the agreement despite having direct relatives who would be released with the amnesty. Then he proposed suspending the agreement until the Ottoman government showed progress in abiding by it, which was rejected by Cemâluddîn. He finally agreed and was designated Consul General in Bordeaux.[17]

The sultan fulfilled his promises except for restoring the constitution and reopening the parliament, which would only happen in 1908 with the Young Turks Revolution.

Consul General in Brussels[edit]

Since the 1897 "truce" Emin Arslan was designated Consul General of the Ottoman Empire in Bordeaux and almost immediately transferred to Brussels, where he stayed at office until 1908.

In Belgium Arslan befriended Roland de Marès (1874–1955), director of L'indépendance belge newspaper, and jurist Ernest Nys.

Despite joining the Ottoman consular service Arslan kept publishing articles, sometime with heavy criticism against the government. As a 1900 article in The Nation quoted:

A new advocate for reform in Turkey has risen in Emin Arslan Effendi, the Consul General in Brussels. Last year he sent to Abdul Hamid a detailed report of the sufferings of the peasants in certain of the richest provinces in the empire. He pointed out that, unable to bear the heavy burden of taxation and the arbitrary methods of the farmers of revenue, they were cutting down their trees, tearing up their vines, leaving their lands uncultivated, and even emigrating in vast numbers beyond the seas. America alone, be said, contained more than 100,000 Syrian emigrants, a third of whom were Mohammedans. "Never in the history of Islam has such a thing occurred." In this year’s report he dwells upon the great numbers of high officials and their enormous salaries. There are in the army, for instance, forty-four marshals, and forty-six viziers with the rank of marshal, and there are eighty members of the Council of State—as many as in France and Germany put together. Mukhtar Pasha's salary is four times as large as Lord Cromer's, and the Grand Vizier receives twice as much as Lord Salisbury. But "as the majority of these high officials receive from the Treasury double and sometimes treble their salaries, the financial embarrassment of the empire is but natural."[18]

A novel that Arslan wrote in Spanish years after, "End of a romance" ("Final de un idilio") is staged in Brussels short before WWI. Its main characters are Van Doren, an army officer and aristocrat, and Riette, a French Alsacian girl. It was first edited in Buenos Aires in 1917.[19]

Travel to Constantinople and the Young Turks Revolution[edit]

Arslan resigned as Ottoman Consul General in Brussels in 1908 and travelled to Constantinople. A month before, the Young Turks Revolution had taken over the power although without deposing Sultan Abdul Hamid II.[citation needed]

During the Ottoman countercoup of 1909, a first cousin of Arslan's, Latakia's representative to the Congress Muhammed Mustafa Emir Arslan Bey, was shot and killed close to the Parliament. Emin Arslan had to take care of his remnants and arrange their transport to Beyrouth. The French newspaper Gil Blas published on 15 April 1909, that "the Emir Arslan, representative for Latakia" had been killed. Some European friends of Emin Arslan thought he was the victim.[17]

Consul General in Paris[edit]

Emin Arslan was designated Consul General in Paris in 1909. Paris' Le Temps informed in September 1909, that "the Turkish government resolved to upgrade its Paris consulate to a general consulate" and that Emir Emin Arslan, former Consul General in Brussels, had been designated as Consul General in Paris.[20]

In his biographic writings Arslan states that he looked for an alternative destination, without elaborating on the reasons. By then, ambassador to France was Na'ūm Pāšā, former mutaṣarrif of Mount Lebanon during Arslan's tenure as mudīr in 1893. Apparently Arslan did not have good relations with Na'ūm; 17 years before, a conflict with him had caused his resignation as mudīr and his exile.[21]

Once Arslan found out about the newly established consular relations between the Ottoman Empire and the Argentine Republic, he asked to be transferred to Buenos Aires.[17]

In Buenos Aires[edit]

Consul General of the Ottoman Empire[edit]

On 11 June 1910, the Ottoman Empire and the Argentine Republic signed an agreement on consular relations and exchanged consuls before the treatise was approved by both the parliaments (the Argentine congress sanctioned law 8184 approving the treatise only on 2 September 1911).[22]

Emir Emin Arslan was to be the first and only consul of the Ottoman Empire in Argentina, because in 1914 the Porte removed Arslan and the German Consulate assumed the representation of Ottoman interests in Argentina. Arslan arrived in Buenos Aires on 29 October 1910, on board of the steamboat Chili, belonging to French firm Messageries Maritimes, "to an exuberant welcome by a crowd of 4000 Ottoman subjects."[23]

Before arriving in Buenos Aires, the 'Chili' made a stop at Rio de Janeiro, where Argentine newspapers of the last weeks were available. Other passengers informed Arslan that during a debate in the Argentine Senate, Senator Manuel Láinez had criticized the Syro-Ottoman immigration deeming it "not useful" because it was purportedly composed of peddlers rather than agricultural workers.

Ottoman immigration had been defended by La Rioja Senator Joaquín V. González. The Senate session was on 12 September 1910, few days before Arslan's arrival to Buenos Aires, on 29 October 1910. Since Arslan was aware of that kind of criticism, right from his first press interviews he announced that he was going to favor the dedication of his fellows to agriculture. Short after his arrival he visited Senator González to thank him for his defense of the Syro-Ottoman community. Since they were both fluent in French they could communicate without a translator. They became close friends until González's demise in December 1923.[24]

Although Arslan had arrived in Argentina without any knowledge of Spanish, short after his arrival he published his first articles in Spanish at Caras y Caretas magazine and started writing a novel: "End of a romance" ("Final de un idilio"). In the long "dedication to general Roca" that opens the novel, Arslan states that he wrote part of the book in "La Larga" Roca's ranch, (Estancia La Larga). The former president died in 1914 before a scheduled second visit of Arslan's to La Larga. The novel's first edition was published in 1917.[19]

While at office as Consul General in Buenos Aires, Arslan wrote for the Revista Argentina de Ciencias Políticas (Argentine Review of Political Science), directed by Rodolfo Rivarola, the following articles: "La joven Turquía y Europa" (Young Turkey and Europe, t. II, pp. 200–215, 1911), "La Tripolitania" (The Tripolitania, t. III, pp. 177–87, 379–90, 1911) and "Historia diplomática de la Europa Balcánica" (Diplomatic History of Balcanic Europe, t. VI, pp. 635–66, 1913).[25]

Resignation as Consul General in Buenos Aires and death sentence in absentia[edit]

Arslan opposed the entry of the Ottoman Empire in World War I and his relation with the Ottoman Foreign Ministry was damaged. He resigned in late 1914. The Ottoman Empire then entrusted its consular relations with Argentina to the German Consul General in Buenos Aires, Rodolfo Bobrik, who demanded Arslan to surrender the consulate and its documentation. Arslan replied that he had not received an official communication from Constantinople ordering him to hand down consular documentation to a foreign official. The German Consul General filed a case before Argentine's Supreme Court. The Court upheld the claim.[26][27]

In an article published in June 1916 on La Nota magazine, Arslan wrote about the death sentence in absentia passed against him after he was declared "firārī", i.e. fugitive. The review's staff organized a banquet in his honor at a restaurant called "Ferrari" after his owner's surname, and published the news under the title "A death sentence celebrated with a banquet." [28]

Creation and direction of La Nota magazine[edit]

Arslan founded and directed weekly La Nota, whose first issue was published on 14 August 1915. During 1916 Carlos Alberto Leumann was its editor-in-chief. A total of 312 issues were edited until discontinuation in 1921.[29]

La Nota was one of the main Argentine literary magazines of its time and among its contributors were Emilio Becher, Arturo Cancela, Juan Pablo Echagüe, Martín Gil, José Ingenieros, Leopoldo Lugones, Ricardo Rojas, José Enrique Rodó, Eduardo Talero, Manuel Ugarte, Joaquín de Vedia, Joaquín V. González, Alfredo L. Palacios, Francisco Grandmontagne, Víctor Pérez Petit, Charles de Soussens, Arturo Marasso, Carlos Ibarguren, Baldomero Fernández Moreno, Carlos Alberto Leumann, Ataliva Herrera, Julio V. González, Enrique Banchs, Arturo Capdevila, Alfonsina Storni, Evar Méndez, Mario Bravo, Alfredo R. Bufano, Alberto Mendióroz, José Gabriel, Pablo Rojas Paz, Alberto Gerchunoff, Juan Carlos Dávalos, Ricardo Güiraldes, Roberto Mariani, Antonio Herrero, Ricardo E. Molinari, Enrique Méndez Calzada, Héctor Lafleur, Sergio Provenzano, Fernando Alonso, Carlos López Buchardo, Ricardo Rojas, Francisco Sicardi, Joaquín de Vedia, Francisco A. Barroetaveña, Juan Zorrilla de San Martín, Amado Nervo and Rubén Darío.[30][31]

La Nota had a strongly anti-German posture during World War I. For instance, poem "Apóstrofe", by Almafuerte, a diatribe against German emperor William II, appeared twice: 15 January and 5 February 1916.[31]

Alfonsina Storni published some of her first works on La Nota during 1916. She was a permanent contributor from 28 March until 21 November 1919.[32][33][34] Her poems “Convalecer” and “Golondrinas” were published in the magazine.

Miguel de Unamuno wrote in a letter to Pedro Jiménez Ilundain on 20 February 1916: "I read quite a lot and write a bit, almost always about the war, especially for Argentina, for La Nación and La Nota (do you know this weekly?)."[35] He considered La Nota "quite an interesting and frankly germanophobe magazine."[36]

During 1916 Pablo Rojas Paz headed the literary criticism section of the magazine.[37]

Argentine citizenship[edit]

In 1921, during the disintegration of the Ottoman Empire, Arslan acquired the Argentine citizenship and made public his reasons:

- (...) I had already taken the resolution of quitting politics and establishing in Argentina seven years ago. The reason is quite simple and I expressed it to the Grand Visir in my aforementioned memorandum: either if Germany triumphed or was defeated we would be defeated. Because our victory would turn us into their subalterns and their defeat would allow the dismantlement of our unity and turn our country into a group of colonies. And I, rather than being the subject of a colony, preferred to be a citizen in a respected State, particularly if it had such an illustrious status as the Argentine State.[38]

Creation and direction of El Lápiz Azul magazine[edit]

In 1925 Arslan founded the "humoristic, political and literary weekly "El Lápiz Azul" (i.e. "The Blue Pencil"). Editor-in-chief was Celso Tíndaro (born Pedro B. Franco, 1894–1947). 47 issues were published from May 1925 to May 1926, including texts from Leopoldo Lugones, Alberto Williams, Eugenio d'Ors and Eduardo Acevedo Díaz.[39][40]

Creation and direction of Al-Istiklal[edit]

In June 1926, Arslan founded Al-Istiklal (الإستقلال), The Independence. The magazine was in Arabic but part of its commercial ads were in Spanish. It came into being as a political and intellectual response to the upheaval caused by the Great Syrian Revolt,[41] and was one of the main Arabic anti-French organs from Argentina/Brazil. Moreover, it represented a particular strand within local pan-Arab/nationalist anti-colonial thought and activism.[42]

Arslan kept editing this newspaper until his demise in January 1943.[43]

Creation of the Druze Benefit Society[edit]

In 1926 Arslan founded the Druze Benefit Society, currently known as Druze Benefit Association (Asociación de Beneficencia Drusa) and located in Buenos Aires.[44]

In popular culture[edit]

- Emir Arslan is a character in Leopoldo Lugones' tale "El puñal" ("The Poignard"), which is part of his 1924 book "Cuentos fatales" ("Fatal Tales").

- A mainly fictional Arslan takes part in one episode of "Roma & Lynch," by Lautaro Ortiz y Pablo Tunica, in Revista Fierro monthly comic magazine.[45]

- Arslan used to spend holidays in Punta del Este since after his arrival in Argentina in 1910. In 1920 he hired French-born architect Eduardo Le Monnier to build a chalet he called "La Chaumière". It was located at the point currently limited by streets Los Muergos, Los Arrecifes, Resalsero and Rambla General Artigas. The contiguous beach is called "El Emir" in his honor.[46]

Works[edit]

- History of Napoleon I (in Arabic), 1892

- The Secrets of the Palaces (in Arabic), 1897[47]

- The Rights of Nations and the Conventions of States (in Arabic), 1900[48]

- The Truth about Hareem (in Spanish), 1916

- End of a Romance (in Spanish), 1917[19]

- Oriental Memoirs (in Spanish), 1918

- The Syrian Revolution against the French Mandate (in Spanish), 1926

- Memoirs (in Arabic), 1934

- Oriental Mysteries (in Spanish), 1932[49]

- The True Story of the Disenchanted (en español), 1935

- The Arabs, Historical-Literary Summary and Legends (in Spanish), 1941[50]

Unpublished works[edit]

Most editions of Arslan's books include a list of unpublished theatrical works that are today lost:

- The Sultana (in 4 acts)

- The Liberator (Life of San Martín, a prologue and 4 acts).

- Love in Diplomacy (3 acts)

- It Was Written (3 acts)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Tornielli, Pablo (July 2015). "El cónsul otomano en Buenos Aires y el genocidio armenio" [The Ottoman consul in Buenos Aires and the Armenian genocide]. Todo es Historia (in Spanish) (576): 26–27. ISSN 0040-8611. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Ziriklī, al, Ḫair ad-Dīn (2002). قاموس تراجم لأشهر الرجال والنساء من العرب والمستعربين والمستشرقين [The Sages. Biographical Encyclopedia of most famous men and women among Arabs, arabists and orientalists] (in Arabic). Vol. II (15 ed.). Beirut: دار العالم للملايين. p. 19.

- ^ "Arslan – أرسلان". Arab Encyclopedia – الموسوعة العربية (in Arabic). Vol. I. Damascus. 1981. p. 888. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link)[permanent dead link] - ^ Arslan, Emin s/ Sucesión – Legajo 32698 – (judicial file). Buenos Aires: Archivo General del Poder Judicial de la Nación, Juzgado Civil 9.

- ^ "La Franc-Maçonnerie au Liban". Grand Orient Arabe Œcuménique (G.O.A.O.) Obédience Maçonnique. Archived from the original on 26 February 2017. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Kayalı, Hasan (1997). Arabs and Young Turks: Ottomanism, Arabism, and Islamism in the Ottoman Empire, 1908–1918. University of California Press. p. 42. ISBN 9780520917576. Retrieved 16 March 2017.

- ^ Daya, Jean (26 June 1999). "أعداد أولى لدوريات مجهولة . "كشف النقاب" الباريسية" [First Issues of Unknown Periodicals: "Kashf an-Niqāb"]. Al Hayat (in Arabic). No. 13258. p. 23. Archived from the original on 13 February 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Arabic Newspapers – K – Kashf al-niqab – Kaschf-ul-nicab". British Library. Archived from the original on 2 December 2014. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Sarkis, Salim (7 September 1901). "France and the Sultan. To the Editor of The New York Times". The New York Times. p. 8. Archived from the original on 20 March 2017. Retrieved 20 March 2017.

France has prevented Ahmad Riza Bey and Khalil Ganem from publishing in Paris the organ of our party, Mashuarat, and even went so far as preventing them from mailing the Turkish edition. Emir Emin Arslan and myself were not allowed to continue publishing in Paris our paper Kashf-ul-nicab, and I remember that the concierge at 21 Rue Valette was ordered by the French police to report the names of our visitors.

- ^ Mardin, Şerif (Spring 1962). "Libertarian Movements in the Ottoman Empire 1878–1895". Middle East Journal. 16 (2): 176. ISSN 0026-3141. JSTOR 4323469.

- ^ Ayalon, Ami (1987). Language and Change in the Arab Middle East: The Evolution of Modern Political Discourse. Oxford University Press. p. 176. ISBN 9780195041408. Retrieved 18 March 2017.

- ^ "Nouvelles diverses". Journal des débats (in French). Paris. 12 October 1879. p. 2. Retrieved 22 March 2017.

Par décret du 27 septembre et sur la proposition du ministre des affaires étrangères, le Président de la république a nommé notre collaborateur Khalil Ghanem chevalier de l'Ordre de la Légion-d'Honneur.

- ^ "La Revue Blanche, v. X and XI". BnF Gallica (in French). Slatkine Reprints. 1896. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Claretie, Jules (1900). "Prologue". Sarcey, Francis, Quarante Ans de Théatre (Feuilletons dramatiques) (in French). Paris: Bibliothéque des Annales Politiques et Littéraires. p. 2.

- ^ Claretie, Jules (1910). Quarante ans Après; Impressions d'Alsace et de Lorraine, 1870–1910 (in French). Paris: Bibliothéque-Charpentier.

- ^ Bey, Murad; Ganem, Halil; Rıza, Ahmed; Arslan, Emin; Salmoné, H. Antony (29 January 1897). "Diario Estero". Gazetta Ufficiale del Regno d'Italia (in Italian) (23). Rome: Project AU.G.U.STO – Automazione Gazzetta Ufficiale Storica: 540. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ a b c d Arslan, Emin (1918). Recuerdos de Oriente (in Spanish) (second ed.). Buenos Aires: Talleres Gráficos La Lectura. pp. 117, 211–212.

- ^ "Notes". The Nation. Vol. 70, no. 1820. New York. 17 May 1900. p. 378. hdl:2027/pst.000068744175. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

- ^ a b c Arslan, Emin (1917). Final de un idilio [End of a Romance] (in Spanish) (first ed.). Buenos Aires: Rodríguez Giles. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ "Emir Emin Arslan, ancien consul général à Bruxelles, est nommé consul général à Paris" [Emir Emin Arslan, former Consul General in Brussels, is designed Consul General in Paris]. Le Temps (in French). No. 17612. Paris: BnF Gallica. 16 September 1909. p. 3. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ نويهض, عجاج; نويهض, خلدون (2010). الأمير أمين أرسلان؛ ناشر ثقافة العرب في الأرجنتين [Emir Emin Arslan: Diffuser of the Arab Culture in Argentine] (in Arabic) (first ed.). Beirut: دار الإستقلال للدراسات والنشر. p. 64. ISBN 9789953570006. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Law 8184 – Approval of a Treatise of Consular Relations between the Argentine Republic and the Ottoman Empire". Sistema Argentino de Información Jurídica (SAIJ). Ministry of Justice. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Hyland, Stephen (August 2011). "'Arisen from Deep Slumber': Transnational Politics and Competing Nationalisms among Syrian Immigrants in Argentina, 1900–1922". Journal of Latin American Studies. 43 (3). Cambridge University Press: 547–574. doi:10.1017/S0022216X11000770. S2CID 147628628. Retrieved 21 March 2017.

After the crowd had waited for more than three hours, Arslan's ship, flying the Ottoman flag at full mast, docked, and bands from the Young Ottoman Society and the Israelite Society performed the Argentine national anthem, the Ottoman hymn and the Marseillaise. Consul Arslan offered words of thanks to the throng of compatriots and to Argentina for its generosity. The reception committee then ushered Arslan into a waiting car and set off for the Plaza Hotel, the fanciest hotel in the capital. The excitement grew when Argentine spectators from the balconies overlooking the famed Calle Florida began saluting the 'colectividad otomana', or Ottoman community, as the marchers below praised Argentina. Once at the hotel, Arslan appeared on a balcony overlooking the assembled Ottoman subjects and the Plaza San Martín and offered his thanks to the organising committee..

- ^ Tornielli, Pablo (March 2015). "El primer cónsul otomano en la Argentina" [The first Ottoman consul in Argentina]. Todo es Historia (in Spanish). 47 (572). Buenos Aires: 6–19. ISSN 0040-8611. Archived from the original on 27 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "Estudio e Índice General 1910–1920" (PDF). Revista Argentina de Ciencias Políticas (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Academia Nacional de Ciencias Morales y Políticas. ISSN 0325-4763. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ El asunto del consulado otomano ante la Suprema Corte. La demanda del cónsul alemán. Contestación del Emir Emin Arslan Archived 19 November 2015 at the Wayback Machine. La Nota, 163–164.

- ^ Corte Suprema de Justicia de la Nación, Fallos 122:129 (1915), "Bobrik, Rodolfo, cónsul general de Alemania c/ Arslan, Emir Emin, cónsul general de Turquía".

- ^ La Nota, Buenos Aires, 10 June 1916, "Reflexiones de un condenado a muerte", nº 44, pp. 862–863 y "Una condena festejada con un banquete".

- ^ Delgado, Verónica (2010). Revista La Nota: antologÌa 1915–1917 (in Spanish) (first ed.). La Plata: Universidad Nacional de la Plata. ISBN 9789503406793. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Lafleur, Héctor René; Provenzano, Sergio D.; Alonso, Fernando (2006). Las revistas literarias argentinas, 1893–1967 (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: El 8vo. loco. p. 80. ISBN 9789872268510. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ a b Minellono, María. "La problemática textual en la poesía de Almafuerte" (PDF) (in Spanish). Poitiers: University of Poitiers, Centre de Recherches Latino-Américains: XXXII. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Diz, Tania (2005). "Periodismo y tecnologías de género en la revista La Nota 1915–18" (PDF). Revista Científica de la Universidad de Ciencias Empresariales y Sociales (in Spanish). IX (1). Buenos Aires: 89–108. ISSN 1514-9358. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Méndez, Claudia Edith (28 July 2004). "Alfonsina Storni: Análisis y contextualización del estilo impresionista en sus crónicas". Digital Repository. Languages, Literatures, & Cultures Theses and Dissertations (in Spanish). College Park, MD: University of Maryland. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Quereilhac, Soledad (20 June 2014). "Con la mira en la mujer futura". La Nación (in Spanish). Buenos Aires. Archived from the original on 28 February 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Unamuno, Miguel de; Robles, Laureano (1996). Epistolario americano (1890–1936) (in Spanish). Salamanca, Spain: Universidad de Salamanca. p. 430. ISBN 9788474819816.

- ^ Tarín-Iglesias, Josefina de; Robles Carcedo, Laureano (October 2000). "Epistolario Miguel de Unamuno – Joaquín Montaner". Cuadernos de la Cátedra Miguel de Unamuno (in Spanish). 35. Salamanca, Spain: Ediciones Universidad de Salamanca: 286. ISSN 0210-749X. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Quién es quién en la Argentina: Biografías contemporáneas [Who is Who in Argentina. Contemporary biographies] (in Spanish) (6 ed.). Buenos Aires: Kraft. 1955. p. 546. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Tornielli, Pablo (30 June 2015). "Hombre de tres mundos. Para una biografía política e intelectual del emir Emín Arslán" [Man of Three Worlds. For a political and intelectual biography of Emir Emin Arslan]. Dirāsāt Hispānicas. Revista Tunecina de Estudios Hispánicos (in Spanish). I (2). Institut Supérieur des Sciences Humaines de Tunis: 157–181. ISSN 2286-5977. Archived from the original on 12 July 2020. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Gasió, Guillermo; García Cedro, Gabriela (2011). Que sean libros en blanco (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Teseo. p. 152. ISBN 9789871354863. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ "El Lápiz Azul". Catálogo de Revistas Culturales Argentinas (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: CeDInCI. Archived from the original on 17 March 2017. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Logroño Narbona, María del Mar (2007). "The 'Woman Question' in the Aftermath of the Great Syrian Revolt: A Transnational Dialogue from the Arab-Argentine Immigrant Press". Al-Raida. XXIV (116). Beirut: Institute for Women's Studies in the Arab World, Lebanese American University: 1–5. ISSN 0259-9953. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Bruckmayr, Philipp (2013). "Arabic Newspapers and Magazines in Latin America". In Ropper, Geoffrey (ed.). Historical Aspects of Printing and Publishing in Languages of the Middle East: Papers from the Symposium at the University of Leipzig, September 2008. BRILL. p. 259. ISBN 9789004255975. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Gasquet, Axel (July 2012). "Historia, leyendas y clichés del Oriente en la obra de Emir Emin Arslán" [History, legends and clichés of the East in the work of Emir Emin Arslan]. Cuadernos del CILHA (in Spanish). 13 (1). Mendoza, Argentina: Centro Interdisciplinario de Literatura Hispanoamericana, Facultad de Filosofía y Letras, Universidad Nacional de Cuyo. ISSN 1852-9615. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Montenegro, Silvia (15 September 2015). "Institutionalizing Islam in Argentina: Comparing Community and Identity Configurations". In Logroño Narbona, María del Mar; Pinto, Paulo G.; Karam, John Tofik (eds.). Crescent Over Another Horizon: Islam in Latin America, the Caribbean, and Latino USA. University of Texas Press. p. 87. ISBN 9781477302293. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Ortiz, Lautaro; Tunica, Pablo (September 2007). "Roma & Lynch". Fierro – la Historieta Argentina (in Spanish) (11). Buenos Aires: Pagina/12: 52–55. ISSN 1514-6855.

- ^ Ponte, Cecilia; Mazzini, Andrés (2001). "Le Monnier en el Uruguay". Le Monnier; arquitectura francesa en la Argentina (in Spanish). Buenos Aires: Fundación CEDODAL. pp. 33–34, 181. ISBN 9871033001. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Arslan, Emin (1897). Asrār al-quṣūr: riwāyaẗ siyāsiyyaẗ tārīẖiyyaẗ ġarāmiyyaẗ adabiyyaẗ [The Secrets of the Palaces – Political, historical and romantic novel] (in Arabic). Cairo. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ Arslan, Emin (1900). Ḥuqūq al-milal wa-muʿāhidāt al-duwal. al-qism al-rābiʿ: fī al-ḥarb [The Rights of Nations and the Conventions of States. Fourth part: On war] (in Arabic) (first ed.). Cairo: Al-Hilal. Retrieved 17 March 2017.

- ^ Arslan, Emin (1932). Misterios de Oriente [Oriental Mysteries] (in Spanish) (2 ed.). Buenos Aires: Tor. Retrieved 19 March 2017.

- ^ Arslan, Emin (1943). Los árabes: reseña histórico-literaria y leyendas [The Arabs, Historical-Literary Summary and Legends] (in Spanish) (3 ed.). Buenos Aires: Sopena.

External links[edit]

- Revista La Nota, digitized by ISLA – Institute of Spanish, Portuguese and Latin American Studies- University of Augsburg.

- Sobre los vínculos entre España y Argentina en La Nota (1915–1917), by Delgado, Verónica, in Memoria Académica, Facultad de Humanidades y Ciencias de la Educación, Olivar, 11 (14), 103–114, 2010.

- Telegraph exchange of Emir Emin Arslan during his tenure as Ottoman Consul General in Brussels.

- Notable personalities of Choueifat, official municipal web site (in Arabic, Emin Arslan is listed in second place).

- Gildas Brégain, « L’influence de la tutelle mandataire française sur l’identification des élites syriennes et libanaises devant la société argentine (1900–1946)», Revue européenne des migrations internationales, vol. 27 – n°3 | 2011, published 1 December 2014, consulted 16 September 2015.

- 1868 births

- 1943 deaths

- People from Aley District

- Arslan family

- Argentine Druze people

- Lebanese emigrants to Argentina

- Emigrants from the Ottoman Empire to Argentina

- Lebanese writers

- Argentine writers in French

- Young Turks

- Lebanese Freemasons

- Argentine Muslims

- Syrian nationalists

- Naturalized citizens of Argentina

- Burials at La Chacarita Cemetery