Massachusetts

Massachusetts | |

|---|---|

| Commonwealth of Massachusetts | |

| Nickname(s): The Bay State (official) The Pilgrim State; The Puritan State The Old Colony State The Baked Bean State[1] | |

| Motto(s): Ense petit placidam sub libertate quietem (Latin) By the sword we seek peace, but peace only under liberty | |

| Anthem: "All Hail to Massachusetts" | |

Map of the United States with Massachusetts highlighted | |

| Country | United States |

| Before statehood | Province of Massachusetts Bay |

| Admitted to the Union | February 6, 1788 (6th) |

| Capital (and largest city) | Boston |

| Largest county or equivalent | Middlesex |

| Largest metro and urban areas | Greater Boston |

| Government | |

| • Governor | Maura Healey (D) |

| • Lieutenant governor | Kim Driscoll (D) |

| Legislature | General Court |

| • Upper house | Senate |

| • Lower house | House of Representatives |

| Judiciary | Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court |

| U.S. senators | Elizabeth Warren (D) Ed Markey (D) |

| U.S. House delegation | 9 Democrats (list) |

| Area | |

• Total | 10,565[2] sq mi (27,363 km2) |

| • Land | 7,800[3] sq mi (20,202 km2) |

| • Water | 2,715 sq mi (7,032 km2) 26.1% |

| • Rank | 44th |

| Dimensions | |

| • Length | 190 mi (296 km) |

| • Width | 115 mi (184 km) |

| Elevation | 508 ft (150 m) |

| Highest elevation | 3,489 ft (1,063.4 m) |

| Lowest elevation (Atlantic Ocean) | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Population (2023) | |

• Total | |

| • Rank | 16th |

| • Density | 891/sq mi (344/km2) |

| • Rank | 3rd |

| • Median household income | $89,026[6] |

| • Income rank | 2nd |

| Demonym | Bay Stater (official)[7]

Masshole[8][9][10][11][12][13] Massachusite (traditional)[14][15] Massachusettsan (recommended by the U.S. GPO)[16] |

| Language | |

| • Official language | English[17] |

| • Spoken language |

|

| Time zone | UTC−05:00 (Eastern) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC−04:00 (EDT) |

| USPS abbreviation | MA |

| ISO 3166 code | US-MA |

| Traditional abbreviation | Mass. |

| Latitude | 41°14′ N to 42°53′ N |

| Longitude | 69°56′ W to 73°30′ W |

| Website | mass |

| List of state symbols | |

|---|---|

| |

| |

| Poem | Blue Hills of Massachusetts[19][20] |

| Slogan | Make It Yours, The Spirit of America[21] |

| Living insignia | |

| Bird | Black-capped chickadee,[22] wild turkey[23][19] |

| Fish | Cod[19][24] |

| Flower | Mayflower[19][25] |

| Insect | Ladybug[19][26] |

| Mammal | Right whale,[27] Morgan horse,[28] Tabby cat,[29] Boston Terrier[30] |

| Reptile | Garter snake[19][31] |

| Tree | American elm[19][32] |

| Inanimate insignia | |

| Beverage | Cranberry juice[19][33] |

| Color(s) | Blue, green, cranberry[19][34] |

| Dance | Square dance[19][35] |

| Food | Cranberry,[36] corn muffin,[19][37] navy bean,[38] Boston cream pie,[39] chocolate chip cookie,[40] Boston cream doughnut[41] |

| Fossil | Dinosaur Tracks[42] |

| Gemstone | Rhodonite[19][43] |

| Mineral | Babingtonite[19][44] |

| Rock | Roxbury Puddingstone[19][45] |

| Shell | New England Neptune, Neptunea lyrata decemcostata[19][46] |

| Ship | Schooner Ernestina[19] |

| Soil | Paxton[19] |

| Sport | Basketball[47] |

| State route marker | |

| |

| State quarter | |

Released in 2000[48] | |

| Lists of United States state symbols | |

Massachusetts (/ˌmæsəˈtʃuːsɪts/ , /-zɪts/ MASS-ə-CHOO-sits, -zits; Massachusett: Muhsachuweesut [məhswatʃəwiːsət]), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts,[b] is a state in the New England region of the Northeastern United States. It borders the Atlantic Ocean and Gulf of Maine to its east, Connecticut and Rhode Island to its south, New Hampshire and Vermont to its north, and New York to its west. Massachusetts is the sixth-smallest state by land area. With over seven million residents as of 2020,[note 1] it is the most populous state in New England, the 16th-most-populous in the country, and the third-most densely populated, after New Jersey and Rhode Island.

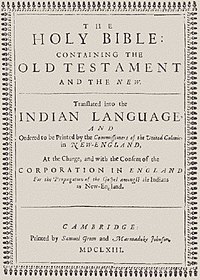

Massachusetts was a site of early English colonization. The Plymouth Colony was founded in 1620 by the Pilgrims of the Mayflower. In 1630, the Massachusetts Bay Colony, taking its name from the Indigenous Massachusett people, also established settlements in Boston and Salem. In 1692, the town of Salem and surrounding areas experienced one of America's most infamous cases of mass hysteria, the Salem witch trials.[49] In the late 18th century, Boston became known as the "Cradle of Liberty"[50] for the agitation there that later led to the American Revolution. In 1786, Shays' Rebellion, a populist revolt led by disaffected American Revolutionary War veterans, influenced the United States Constitutional Convention.[51] Originally dependent on agriculture, fishing, and trade,[52] Massachusetts was transformed into a manufacturing center during the Industrial Revolution.[53] Before the American Civil War, the state was a center for the abolitionist, temperance,[54] and transcendentalist[55] movements.[56] During the 20th century, the state's economy shifted from manufacturing to services;[57] and in the 21st century, Massachusetts has become the global leader in biotechnology,[58] and also excels in artificial intelligence,[59] engineering, higher education, finance, and maritime trade.[60]

The state's capital and most populous city, as well as its cultural and financial center, is Boston. Other major cities are Worcester, Springfield and Cambridge. Massachusetts is also home to the urban core of Greater Boston, the largest metropolitan area in New England and a region profoundly influential upon American history, academia, and the research economy.[61] Massachusetts has a reputation for social and political progressivism;[62] becoming the only U.S. state with a right to shelter law, and the first U.S. state, and one of the earliest jurisdictions in the world to legally recognize same-sex marriage.[63] Harvard University in Cambridge is the oldest institution of higher learning in the United States,[64] with the largest financial endowment of any university in the world.[65] Both Harvard and MIT, also in Cambridge, are perennially ranked as either the most or among the most highly regarded academic institutions in the world.[66] Massachusetts's public-school students place among the top tier in the world in academic performance.[67]

Massachusetts is the most educated[68] and one of the most highly developed and wealthiest U.S. states, ranking first in the percentage of population 25 and over with either a bachelor's degree or advanced degree, first on both the American Human Development Index and the standard Human Development Index, first in per capita income, and as of 2023, first in median income.[68] Consequently, Massachusetts typically ranks as the top U.S. state,[69] as well as the most expensive state, for residents to live in.[70]

Etymology

[edit]The Massachusetts Bay Colony was named after the Indigenous population, the Massachusett or Muhsachuweesut, whose name likely derived from a Wôpanâak word muswachasut, segmented as mus(ây) "big" + wach "mountain" + -s "diminutive" + -ut "locative".[71] This word has been translated as "near the great hill",[72] "by the blue hills", "at the little big hill", or "at the range of hills", in reference to the Blue Hills—namely, the Great Blue Hill, located on the boundary of Milton and Canton.[73][74] Massachusett has also been represented as Moswetuset. This comes from the name of the Moswetuset Hummock (meaning "hill shaped like an arrowhead") in Quincy, where Plymouth Colony commander Myles Standish (a hired English military officer) and Squanto (a member of the Patuxet band of the Wamponoag people, who have since died off due to contagious diseases brought by colonists) met Chief Chickatawbut in 1621.[75][76]

Although the designation "Commonwealth" forms part of the state's official name, it has no practical implications in modern times,[77] and Massachusetts has the same position and powers within the United States as other states.[78] John Adams may have chosen the word in 1779 for the second draft of what became the 1780 Massachusetts Constitution; unlike the word "state", the word "commonwealth" had the connotation of a republic at the time. This was in contrast to the monarchy the former colonies were fighting against during the American Revolutionary War. The name "State of Massachusetts Bay" appeared in the first draft, which was ultimately rejected. It was also chosen to include the "Cape Islands" in reference to Martha's Vineyard and Nantucket—from 1780 to 1844, they were seen as additional and separate entities confined within the Commonwealth.[79]

History

[edit]Pre-colonization

[edit]Massachusetts was originally inhabited by tribes of the Algonquian language family, including Wampanoag, Narragansett, Nipmuc, Pocomtuc, Mahican, and Massachusett.[80][81] While cultivation of crops like squash and corn were an important part of their diet, the people of these tribes hunted, fished, and searched the forest for most of their food.[80] Villagers lived in lodges called wigwams as well as longhouses.[81] Tribes were led by male or female elders known as sachems.[82]

Colonial period

[edit]

In the early 1600s, European colonists caused virgin soil epidemics such as smallpox, measles, influenza, and perhaps leptospirosis in what is now known as the northeastern region of the United States.[83][84] Between 1617 and 1619, a disease that was most likely smallpox killed approximately 90% of the Massachusetts Bay Native Americans.[85]

The first English colonists in Massachusetts Bay Colony landed with Richard Vines and spent the winter in Biddeford Pool near Cape Porpoise (after 1820 the State of Maine) in 1616. The Puritans, arrived at Plymouth in 1620. This was the second permanent English colony in the part of North America that later became the United States, after the Jamestown Colony. The "First Thanksgiving" was celebrated by the Puritans after their first harvest in the "New World" and lasted for three days. They were soon followed by other Puritans, who colonized the Massachusetts Bay Colony—now known as Boston—in 1630.[86]

The Puritans believed the Church of England needed to be further reformed along Protestant Calvinist lines, and experienced harassment due to the religious policies of King Charles I and high-ranking churchmen such as William Laud, who would become Charles's Archbishop of Canterbury, whom they feared were re-introducing "Romish" elements to the national church.[87] They decided to colonize to Massachusetts, intending to establish what they considered an "ideal" religious society.[88] The Massachusetts Bay Colony was colonized under a royal charter, unlike the Plymouth colony, in 1629.[89] Both religious dissent and expansionism resulted in several new colonies being founded, shortly after Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay, elsewhere in New England. The Massachusetts Bay banished dissenters such as Anne Hutchinson and Roger Williams due to religious and political conflict. In 1636, Williams colonized what is now known as Rhode Island, and Hutchinson joined him there several years later. Religious intolerance continued, and among those who objected to this later that century were the English Quaker preachers Alice and Thomas Curwen, who were publicly flogged and imprisoned in Boston in 1676.[90][91]

By 1641, Massachusetts had expanded inland significantly. The Commonwealth acquired the Connecticut River Valley settlement of Springfield, which had recently disputed with—and defected from—its original administrators, the Connecticut Colony.[92] This established Massachusetts's southern border in the west.[93] However, this became disputed territory until 1803–04 due to surveying problems, leading to the modern Southwick Jog.[94]

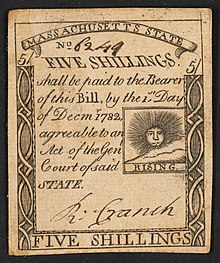

In 1652 the Massachusetts General Court authorized Boston silversmith John Hull to produce local coinage in shilling, sixpence and threepence denominations to address a coin shortage in the colony.[95] Before that point, the colony's economy had been entirely dependent on barter and foreign currency, including English, Spanish, Dutch, Portuguese and counterfeit coins.[96] In 1661, shortly after the restoration of the British monarchy, the British government considered the Boston mint to be treasonous.[97] However, the colony ignored the English demands to cease operations until at least 1682, when Hull's contract as mintmaster expired, and the colony did not move to renew his contract or appoint a new mintmaster.[98] The coinage was a contributing factor to the revocation of the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter in 1684.[99]

In 1691, the colonies of Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth were united (along with present-day Maine, which had previously been divided between Massachusetts and New York) into the Province of Massachusetts Bay.[100] Shortly after, the new province's first governor, William Phips, arrived. The Salem witch trials also took place, where a number of men and women were hanged for alleged witchcraft.[101]

The most destructive earthquake known to date in New England occurred on November 18, 1755, causing considerable damage across Massachusetts.[102][103]

The Revolutionary War

[edit]

Massachusetts was a center of the movement for independence from Great Britain. Colonists in Massachusetts had long had uneasy relations with the British monarchy, including open rebellion under the Dominion of New England in the 1680s.[100] Protests against British attempts to tax the colonies after the French and Indian War ended in 1763 led to the Boston Massacre in 1770, and the 1773 Boston Tea Party escalated tensions.[104] In 1774, the Intolerable Acts targeted Massachusetts with punishments for the Boston Tea Party and further decreased local autonomy, increasing local dissent.[105] Anti-Parliamentary activity by men such as Samuel Adams and John Hancock, followed by reprisals by the British government, were a primary reason for the unity of the Thirteen Colonies and the outbreak of the American Revolution in 1775.[106]

The Battles of Lexington and Concord, fought in Massachusetts in 1775, initiated the American Revolutionary War.[107] George Washington, later the first president of the future country, took over what would become the Continental Army after the battle. His first victory was the siege of Boston in the winter of 1775–76, after which the British were forced to evacuate the city.[108] The event is still celebrated in Suffolk County only every March 17 as Evacuation Day.[109]

On the coast, Salem became a center for privateering. Although the documentation is incomplete, about 1,700 letters of marque, issued on a per-voyage basis, were granted during the American Revolution. Nearly 800 vessels were commissioned as privateers, which were credited with capturing or destroying about 600 British ships.[110]

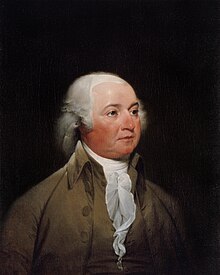

Federal period

[edit]Bostonian John Adams, known as the "Atlas of Independence",[111] was highly involved in both separation from Britain and the Constitution of Massachusetts, which effectively (the Elizabeth Freeman and Quock Walker cases as interpreted by William Cushing) made Massachusetts the first state to abolish slavery. David McCullough points out that an equally important feature was its placing for the first time the courts as a co-equal branch separate from the executive.[112] (The Constitution of Vermont, adopted in 1777, represented the first partial ban on slavery among the states. Vermont became a state in 1791 but did not fully ban slavery until 1858 with the Vermont Personal Liberty Law. The Pennsylvania Gradual Abolition Act of 1780[113] made Pennsylvania the first state to abolish slavery by statute - the second English colony to do so; the first having been the Colony of Georgia in 1735.) Later, Adams was active in early American foreign affairs and succeeded Washington as the second president of the United States. His son, John Quincy Adams, also from Massachusetts,[114] would go on to become the nation's sixth president.

From 1786 to 1787, an armed uprising led by Revolutionary War veteran Daniel Shays, now known as Shays' Rebellion, wrought havoc throughout Massachusetts and ultimately attempted to seize the federal Springfield Armory.[51] The rebellion was one of the major factors in the decision to draft a stronger national constitution to replace the Articles of Confederation.[51] On February 6, 1788, Massachusetts became the sixth state to ratify the United States Constitution.[115]

19th century

[edit]In 1820, Maine separated from Massachusetts and entered the Union as the 23rd state due to the ratification of the Missouri Compromise.[116]

During the 19th century, Massachusetts became a national leader in the American Industrial Revolution, with factories around cities such as Lowell and Boston producing textiles and shoes, and factories around Springfield producing tools, paper, and textiles.[117][118] The state's economy transformed from one based primarily on agriculture to an industrial one, initially making use of water-power and later the steam engine to power factories. Canals and railroads were being used in the state for transporting raw materials and finished goods.[119] At first, the new industries drew labor from Yankees on nearby subsistence farms, though they later relied upon immigrant labor from Europe and Canada.[120][121]

Although Massachusetts was the first slave-holding colony with slavery dating back to the early 1600s, the state became a center of progressivist and abolitionist (anti-slavery) activity in the years leading up to the American Civil War. Horace Mann made the state's school system a national model.[122] Henry David Thoreau and Ralph Waldo Emerson, both philosophers and writers from the state, also made major contributions to American philosophy.[123] Furthermore, members of the transcendentalist movement within the state emphasized the importance of the natural world and emotion to humanity.[123]

Although significant opposition to abolitionism existed early on in Massachusetts, resulting in anti-abolitionist riots between 1835 and 1837,[124] abolitionist views there gradually increased throughout the next few decades.[125][126] Abolitionists John Brown and Sojourner Truth lived in Springfield and Northampton, respectively, while Frederick Douglass lived in Boston and Susan B. Anthony in Adams. The works of such abolitionists contributed to Massachusetts's actions during the Civil War. Massachusetts was the first state to recruit, train, and arm a Black regiment with White officers, the 54th Massachusetts Infantry Regiment.[127] In 1852, Massachusetts became the first state to pass compulsory education laws.[128]

20th century

[edit]Although the U.S. stock market had sustained steep losses the last week in October 1929, Tuesday, October 29 is remembered as the beginning of the Great Depression. The Boston Stock Exchange, drawn into the whirlpool of panic selling that beset the New York Stock Exchange, lost over 25 percent of its value in two days of frenzied trading. The BSE, nearly 100 years old at the time, had helped raise the capital that had funded many of the Commonwealth's factories, railroads, and businesses. "[129] Governor of Massachusetts Frank G. Allen appointed John C. Hull the first Securities Director of Massachusetts.[130][131][132] Hull would assume office in January 1930, and his term would end in 1936.[133]

With the departure of several manufacturing companies, the state's industrial economy began to decline during the early 20th century. By the 1920s, competition from the American South and Midwest, followed by the Great Depression, led to the collapse of the three main industries in Massachusetts: textiles, shoemaking, and precision mechanics.[134] This decline would continue into the latter half of the 20th century. Between 1950 and 1979, the number of Massachusetts residents involved in textile manufacturing declined from 264,000 to 63,000.[135] The 1969 closure of the Springfield Armory, in particular, spurred an exodus of high-paying jobs from Western Massachusetts, which suffered greatly as it de-industrialized during the century's last 40 years.[136]

Massachusetts manufactured 3.4 percent of total United States military armaments produced during World War II, ranking tenth among the 48 states.[137] After the world war, the economy of eastern Massachusetts transformed from one based on heavy industry into a service-based economy.[138] Government contracts, private investment, and research facilities led to a new and improved industrial climate, with reduced unemployment and increased per capita income. Suburbanization flourished, and by the 1970s, the Route 128/Interstate 95 corridor was dotted with high-tech companies who recruited graduates of the area's many elite institutions of higher education.[139]

In 1987, the state received federal funding for the Central Artery/Tunnel Project. Commonly known as "the Big Dig", it was, at the time, the biggest federal highway project ever approved.[140] The project included making the Central Artery, part of Interstate 93, into a tunnel under downtown Boston, in addition to the re-routing of several other major highways.[141][failed verification] The project was often controversial, with numerous claims of graft and mismanagement, and with its initial price tag of $2.5 billion increasing to a final tally of over $15 billion. Nonetheless, the Big Dig changed the face of Downtown Boston[140] and connected areas that were once divided by elevated highway. Much of the raised old Central Artery was replaced with the Rose Fitzgerald Kennedy Greenway. The project also improved traffic conditions along several routes.[140][141]

Notable 20th century politicians

[edit]

The Kennedy family was prominent in 20th-century Massachusetts politics. The children of businessman and ambassador Joseph P. Kennedy Sr. included John F. Kennedy, who was a senator and U.S. president before his assassination in 1963; Ted Kennedy, a senator from 1962 until his death in 2009;[142] and Eunice Kennedy Shriver, a co-founder of the Special Olympics.[143] In 1966, Massachusetts became the first state to directly elect an African American to the U.S. senate with Edward Brooke.[144] George H. W. Bush, 41st President of the United States (1989–1993) was born in Milton in 1924.[145]

Other notable Massachusetts politicians on the national level included Joseph W. Martin Jr., Speaker of the House (from 1947 to 1949 and then again from 1953 to 1955) and leader of House Republicans from 1939 until 1959 (where he was the only Republican to serve as Speaker between 1931 and 1995),[146] John W. McCormack, Speaker of the House in the 1960s, and Tip O'Neill, whose service as Speaker of the House from 1977 to 1987 was the longest continuous tenure in United States history.[147]

21st century

[edit]On May 17, 2004, Massachusetts became the first state in the U.S. to legalize same-sex marriage. This followed the Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court's decision in Goodridge v. Department of Public Health in November 2003, which determined that the exclusion of same-sex couples from the right to a civil marriage was unconstitutional.[63]

In 2004, Massachusetts senator John Kerry, who won the Democratic nomination for President of the United States, lost to incumbent George W. Bush. Eight years later, former Massachusetts governor Mitt Romney (the Republican nominee) lost to incumbent Barack Obama in 2012. Another eight years later, Massachusetts senator Elizabeth Warren became a frontrunner in the Democratic primaries for the 2020 presidential election. However, she later suspended her campaign and endorsed presumptive nominee Joe Biden.[148]

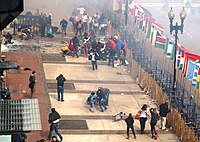

Two pressure cooker bombs exploded near the finish line of the Boston Marathon on April 15, 2013, at around 2:49 pm local time (EDT). The explosions killed three people and injured an estimated 264 others.[149] The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) later identified the suspects as brothers Dzhokhar Tsarnaev and Tamerlan Tsarnaev. The ensuing manhunt ended on April 19 when thousands of law enforcement officers searched a 20-block area of nearby Watertown. Dzhokhar later said he was motivated by extremist Islamic beliefs and learned to build explosive devices from Inspire, the online magazine of al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.[150]

On November 8, 2016, Massachusetts voted in favor of the Massachusetts Marijuana Legalization Initiative, also known as Question 4.[151]

Geography

[edit]

Massachusetts is the seventh-smallest state in the United States.[152] It is located in the New England region of the Northeastern United States.[153] It has an area of 10,555 square miles (27,340 km2),[154] 25.7% of which is water.[155] Several large bays distinctly shape its coast, giving it the nickname "the Bay State".[156] Boston is its largest city.[157]

Despite its small size, Massachusetts features numerous topographically distinctive regions. The large coastal plain of the Atlantic Ocean in the eastern section of the state contains Greater Boston, along with most of the state's population,[61] as well as the distinctive Cape Cod peninsula. To the west lies the hilly, rural region of Central Massachusetts, and beyond that, the Connecticut River Valley. Along the western border of Western Massachusetts lies the highest elevated part of the state, the Berkshires, forming a portion of the northern terminus of the Appalachian Mountains.[citation needed]

The U.S. National Park Service administers a number of natural and historical sites in Massachusetts.[158] Along with twelve national historic sites, areas, and corridors, the National Park Service also manages the Cape Cod National Seashore and the Boston Harbor Islands National Recreation Area.[158] In addition, the Department of Conservation and Recreation maintains a number of parks, trails, and beaches throughout Massachusetts.[159]

Ecology

[edit]The primary biome of inland Massachusetts is temperate deciduous forest.[160] Although much of Massachusetts had been cleared for agriculture, leaving only traces of old-growth forest in isolated pockets, secondary growth has regenerated in many rural areas as farms have been abandoned.[161] Forests cover around 62% of Massachusetts.[162] The areas most affected by human development include the Greater Boston area in the east and the Springfield metropolitan area in the west, although the latter includes agricultural areas throughout the Connecticut River Valley.[163] There are 219 endangered species in Massachusetts.[164]

A number of species are doing well in the increasingly urbanized Massachusetts. Peregrine falcons utilize office towers in larger cities as nesting areas,[165] and the population of coyotes, whose diet may include garbage and roadkill, has been increasing in recent decades.[166] White-tailed deer, raccoons, wild turkeys, and eastern gray squirrels are also found throughout Massachusetts. In more rural areas in the western part of Massachusetts, larger mammals such as moose and black bears have returned, largely due to reforestation following the regional decline in agriculture.[167]

Massachusetts is located along the Atlantic Flyway, a major route for migratory waterfowl along the eastern coast.[168] Lakes in central Massachusetts provide habitat for many species of fish and waterfowl, but some species such as the common loon are becoming rare.[169] A significant population of long-tailed ducks winter off Nantucket. Small offshore islands and beaches are home to roseate terns and are important breeding areas for the locally threatened piping plover.[170] Protected areas such as the Monomoy National Wildlife Refuge provide critical breeding habitat for shorebirds and a variety of marine wildlife including a large population of grey seals. Since 2009, there has been a significant increase in the number of Great white sharks spotted and tagged in the coastal waters off of Cape Cod.[171][172][173]

Freshwater fish species in Massachusetts include bass, carp, catfish, and trout, while saltwater species such as Atlantic cod, haddock, and American lobster populate offshore waters.[174] Other marine species include Harbor seals, the endangered North Atlantic right whales, as well as humpback whales, fin whales, minke whales, and Atlantic white-sided dolphins.[175]

The European corn borer, a significant agricultural pest, was first found in North America near Boston, Massachusetts in 1917.[176]

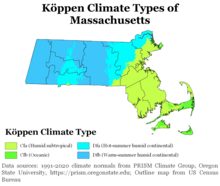

Climate

[edit]Most of Massachusetts has a humid continental climate, with cold winters and warm summers. Far southeast coastal areas are the broad transition zone to Humid Subtropical climates. The warm to hot summers render the oceanic climate rare in this transition, only applying to exposed coastal areas such as on the peninsula of Barnstable County. The climate of Boston is quite representative for the commonwealth, characterized by summer highs of around 81 °F (27 °C) and winter highs of 35 °F (2 °C), and is quite wet. Frosts are frequent all winter, even in coastal areas due to prevailing inland winds. Boston has a relatively sunny climate for a coastal city at its latitude, averaging over 2,600 hours of sunshine a year.

| Location | July (°F) | July (°C) | January (°F) | January (°C) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Boston | 81/65 | 27/18 | 36/22 | 2/−5 |

| Worcester | 79/61 | 26/16 | 31/17 | 0/−8 |

| Springfield | 84/62 | 27/17 | 34/17 | 1/−8 |

| New Bedford | 80/65 | 26/18 | 37/23 | 3/−4 |

| Quincy | 80/61 | 26/16 | 33/18 | 1/−7 |

| Plymouth | 80/61 | 27/16 | 38/20 | 3/−6 |

Environmental issues

[edit]Climate change

[edit]Climate change in Massachusetts will affect both urban and rural environments, including forestry, fisheries, agriculture, and coastal development.[178][179][180] The Northeast is projected to warm faster than global average temperatures; by 2035, according to the U. S. Global Change Research Program, the Northeast is "projected to be more than 3.6°F (2°C) warmer on average than during the preindustrial era".[180] As of August 2016, the EPA reports that Massachusetts has warmed by over two degrees Fahrenheit, or 1.1 degrees Celsius.[181]

Shifting temperatures also result in the shifting of rainfall patterns and the intensification of precipitation events. To that end, average precipitation in the Northeast United States has risen by ten percent from 1895 to 2011, and the number of heavy precipitation events has increased by seventy percent during that time.[181] These increased precipitation patterns are focused in the winter and spring. Increasing temperatures coupled with increasing precipitation will result in earlier snow melts and subsequent drier soil in the summer months.[182]

The shifting climate in Massachusetts will result in a significant change to the state's built environment and ecosystems. In Boston alone, costs of climate change-related storms will result in $5 to $100 billion in damage.[181]

Warmer temperatures will also disrupt bird migration and flora blooming. With these changes, deer populations are expected to increase, resulting in a decrease in underbrush which smaller fauna use as camouflage. Additionally, rising temperatures will increase the number of reported Lyme disease cases in the state. Ticks can transmit the disease once temperatures reach 45 degrees, so shorter winters will increase the window of transmission. These warmer temperatures will also increase the prevalence of Asian tiger mosquitoes, which often carry the West Nile virus.[181]

To fight this change, the Massachusetts Executive Office of Energy and Environmental Affairs has outlined a path to decarbonize the state's economy. On April 22, 2020, Kathleen A. Theoharides, the state's Secretary of Energy and Environmental Affairs, released a Determination of Statewide Emissions limits for 2050. In her letter, Theoharides stresses that as of 2020, the Commonwealth has experienced property damage attributable to climate change of more than $60 billion. To ensure that the Commonwealth experiences warming no more than 1.5 °C of pre-industrialization levels, the state will work towards two goals by 2050: to achieve net-zero emissions, and to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 85 percent overall.[183]

Power initiatives

[edit]The State of Massachusetts has developed a plethora of incentives to encourage the implementation of renewable energy and efficient appliances and home facilities. The Mass Save program, formed in conjunction with the State by several companies that provide power and gas in Massachusetts, provides homeowners and renters with monetary incentives to retrofit their homes with efficient HVAC equipment and other household appliances. Appliances such as water heaters, air conditioners, washers and driers, and heat pumps are eligible for rebates in order to incentivize change.[184]

The concept of Mass Save was created in 2008 by the passing of the Green Communities Act of 2008, during Deval Patrick's tenure as governor. The main goal of the Green Communities Act was to reduce the consumption of fossil fuels in the State and to encourage new, more efficient technologies. Among others, one result of this act was a requirement for Program Administrators of utilities to invest in saving energy, as opposed to purchasing and generating additional energy where economically feasible. In Massachusetts, eleven Program Administrators, including Eversource, National Grid, Western Massachusetts Electric, Cape Light Compact, Until, and Berkshire Gas, jointly own the rights to this program, in conjunction with the MA Department of Energy Resources (DOER) and the Energy Efficiency Advisory Council (EEAC).[185]

The State Revenue Service provides incentives for the installation of solar panels. In addition to the Federal Residential Renewable energy credit, Massachusetts residents may be eligible for a tax credit of up to 15 percent of the project.[186] Once installed, arrays are eligible for net metering.[187] Certain municipalities will offer up to $1.20 per watt, up to 50 percent of the system's cost on PV arrays 25 kW or less.[188] The Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources also offered low-interest, fixed-rate financing with loan support for low-income residents until December 31, 2020.[189]

As a part of the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources' effort to incentivize the usage of renewable energy, the Massachusetts Offers Rebates for Electric Vehicles (MOR-EV) initiative was created. With this incentive, residents may qualify for a state-provided incentive of up to $2,500 for the purchase or lease of an electric vehicle, or $1,500 for the purchase or lease of a plug-in hybrid vehicle.[190] This rebate is available in addition to the tax credits offered by the United States Department of Energy for the purchase of electric and plug-in hybrid vehicles.[191]

For income-eligible residents, Mass Save has partnered with Massachusetts Community Action Program Agencies and Low-Income Energy Affordability Network (LEAN) to offer residents assistance with upgrades to their homes that will result in more efficient energy usage. Residents may qualify for a replacement of their heating system, insulation installation, appliances, and thermostats if they meet the income qualifications provided on Mass Save's website. For residents of 5+ family residential buildings, there are additional income-restricted benefits available through LEAN. If at least 50 percent of the residents of the building qualify as low income, energy efficiency improvements like those available through Mass Save are available. Residential structures operated by non-profit organizations, for profit operations, or housing authorities may take advantage of these programs.[192]

In late 2020, the administration of Massachusetts governor Charlie Baker released a decarbonization roadmap to aim for net-zero greenhouse gas emissions by 2050. The plan calls for major investments in offshore wind and solar energy. It would also require all new cars sold in the state to be zero-emissions (electric or hydrogen powered) by 2035.[193][194]

Demographics

[edit]

| Census | Pop. | Note | %± |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1790 | 378,787 | — | |

| 1800 | 422,845 | 11.6% | |

| 1810 | 472,040 | 11.6% | |

| 1820 | 523,287 | 10.9% | |

| 1830 | 610,408 | 16.6% | |

| 1840 | 737,699 | 20.9% | |

| 1850 | 994,514 | 34.8% | |

| 1860 | 1,231,066 | 23.8% | |

| 1870 | 1,457,351 | 18.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,783,085 | 22.4% | |

| 1890 | 2,238,947 | 25.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,805,346 | 25.3% | |

| 1910 | 3,366,416 | 20.0% | |

| 1920 | 3,852,356 | 14.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,249,614 | 10.3% | |

| 1940 | 4,316,721 | 1.6% | |

| 1950 | 4,690,514 | 8.7% | |

| 1960 | 5,148,578 | 9.8% | |

| 1970 | 5,689,170 | 10.5% | |

| 1980 | 5,737,037 | 0.8% | |

| 1990 | 6,016,425 | 4.9% | |

| 2000 | 6,349,097 | 5.5% | |

| 2010 | 6,547,629 | 3.1% | |

| 2020 | 7,029,917 | 7.4% | |

| 2023 (est.) | 7,001,399 | −0.4% | |

| [195][196] | |||

At the 2020 U.S. census, Massachusetts had a population of over 7 million, a 7.4% increase since the 2010 United States Census.[197][198] As of 2015, Massachusetts was estimated to be the third-most densely populated U.S. state, with 871.0 people per square mile,[199] behind New Jersey and Rhode Island. In 2014, Massachusetts had 1,011,811 foreign-born residents or 15% of the population.[199] As of July 2023, the population is estimated to be 7,001,399.[5]

Most Massachusetts residents live within the Boston metropolitan area, also known as Greater Boston, which includes Boston and its proximate surroundings but also extending to Greater Lowell and to Worcester. The Springfield metropolitan area, also known as Greater Springfield, is also a major center of population. Demographically, the center of population of Massachusetts is located in the town of Natick.[200][201]

Like the rest of the Northeastern United States, the population of Massachusetts has continued to grow in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. Massachusetts is the fastest-growing state in New England and the 25th fastest-growing state in the United States.[202] Population growth has been driven primarily by the relatively high quality of life and a large higher education system.[202]

Foreign immigration is also a factor in the state's population growth, causing the state's population to continue to grow as of the 2010 census (particularly in Massachusetts gateway cities where costs of living are lower).[203][204] Forty percent of foreign immigrants were from Central or South America, according to a 2005 Census Bureau study, with many of the remainder from Asia. Many residents who have settled in Greater Springfield claim Puerto Rican descent.[203] Many areas of Massachusetts showed relatively stable population trends between 2000 and 2010.[204] Exurban Boston and coastal areas grew the most rapidly, while Berkshire County in far Western Massachusetts and Barnstable County on Cape Cod were the only counties to lose population as of the 2010 census.[204] In 2018, The top countries of origin for Massachusetts' immigrants were China, the Dominican Republic, Brazil, India and Haiti.[205]

By sex, 48.4% were male, and 51.6% were female in 2014. In terms of age, 79.2% were over 18 and 14.8% were over 65.[199]

According to HUD's 2022 Annual Homeless Assessment Report, there were an estimated 15,507 homeless people in Massachusetts.[206][207]

Race and ancestry

[edit]

| Race and Ethnicity[209] | Alone | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| White (non-Hispanic) | 67.6% | 71.4% | ||

| Hispanic or Latino[c] | — | 12.6% | ||

| African American (non-Hispanic) | 6.5% | 8.2% | ||

| Asian | 7.2% | 8.2% | ||

| Native American | 0.1% | 0.9% | ||

| Pacific Islander | 0.02% | 0.1% | ||

| Other | 1.3% | 3.6% | ||

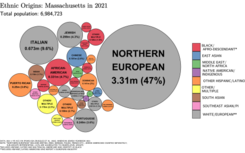

The state's most populous ethnic group, non-Hispanic white, has declined from 95.4% in 1970 to 67.6% in 2020.[199][210] As of 2011, non-Hispanic whites were involved in 63.6% of all the births,[211] while 36.4% of the population of Massachusetts younger than age 1 was minorities (at least one parent who was not non-Hispanic white).[212] One major reason for this is that non-Hispanic whites in Massachusetts recorded a total fertility rate of 1.36 in 2017, the second-lowest in the country after neighboring Rhode Island.[213]

As late as 1795, the population of Massachusetts was nearly 95% of English ancestry.[214] During the early and mid-19th century, immigrant groups began arriving in Massachusetts in large numbers; first from Ireland in the 1840s;[215] today the Irish and part-Irish are the largest ancestry group in the state at nearly 25% of the total population. Others arrived later from Quebec as well as places in Europe such as Italy, Portugal, and Poland.[216] In the early 20th century, an increasing number of African Americans migrated to Massachusetts, although in somewhat fewer numbers than many other Northern states.[217] Later in the 20th century, immigration from Latin America increased considerably. More than 156,000 Chinese Americans made their home in Massachusetts in 2014,[218] and Boston hosts a growing Chinatown accommodating heavily traveled Chinese-owned bus lines to and from Chinatown, Manhattan in New York City. Massachusetts also has large Dominican, Puerto Rican, Haitian, Cape Verdean and Brazilian populations.[219] Boston's South End and Jamaica Plain are both gay villages, as is nearby Provincetown, Massachusetts on Cape Cod.[220]

The largest ancestry group in Massachusetts are the Irish (22.5% of the population), who live in significant numbers throughout the state but form more than 40% of the population along the South Shore in Norfolk and Plymouth counties (in both counties overall, Irish-Americans comprise more than 30% of the population). Italians form the second-largest ethnic group in the state (13.5%), but form a plurality in some suburbs north of Boston and in a few towns in the Berkshires. English Americans, the third-largest (11.4%) group, form a plurality in some western towns. French and French Canadians also form a significant part (10.7%),[221] with sizable populations in Bristol, Hampden, and Worcester Counties, along with Middlesex county especially concentrated in the areas surrounding Lowell and Lawrence.[222][223] Lowell is home to the second-largest Cambodian community of the nation.[224] Massachusetts is home to a small community of Greek Americans as well, which according to the American Community Survey there are 83,701 of them scattered along the state (1.2% of the total state population).[225] There are also several populations of Native Americans in Massachusetts. The Wampanoag tribe maintains reservations at Aquinnah on Martha's Vineyard and at Mashpee on Cape Cod—with an ongoing native language revival project underway since 1993, while the Nipmuc maintain two state-recognized reservations in the central part of the state, including one at Grafton.[226]

Massachusetts has avoided many forms of racial strife seen elsewhere in the US, but examples such as the successful electoral showings of the nativist (mainly anti-Catholic) Know Nothings in the 1850s,[227] the controversial Sacco and Vanzetti executions in the 1920s,[228] and Boston's opposition to desegregation busing in the 1970s.[229]

Historical racial and ethnic composition

Massachusetts – Racial and Ethnic Composition

(NH = Non-Hispanic)

Note: the US Census treats Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic category. This table excludes Latinos from the racial categories and assigns them to a separate category. Hispanics/Latinos may be of any race.

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2000[230] | Pop 2010[231] | Pop 2020[232] | %2000 | %2010 | %2020 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| White alone (NH) | 5,198,359 | 4,984,800 | 4,748,897 | 81.88% | 76.13% | 67.55% |

| Black or African American alone (NH) | 318,329 | 391,693 | 457,055 | 5.01% | 5.98% | 6.5% |

| Native American or Alaska Native alone (NH) | 11,264 | 10,788 | 9,378 | 0.18% | 0.16% | 0.13% |

| Asian alone (NH) | 236,786 | 347,495 | 504,900 | 3.73% | 5.31% | 7.18% |

| Pacific Islander alone (NH) | 1,706 | 1,467 | 1,607 | 0.03% | 0.02% | 0.02% |

| Some Other Race alone (NH) | 43,586 | 61,547 | 92,108 | 0.69% | 0.94% | 1.31% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (NH) | 110,338 | 122,195 | 328,278 | 1.74% | 1.87% | 4.67% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 428,729 | 627,654 | 887,685 | 6.75% | 9.59% | 12.63% |

| Total | 6,349,097 | 6,547,629 | 7,029,917 | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Languages

[edit]The most common varieties of American English spoken in Massachusetts, other than General American, are the cot-caught distinct, rhotic, western Massachusetts dialect and the cot-caught merged, non-rhotic, eastern Massachusetts dialect (popularly known as a "Boston accent").[233]

| Language | Percentage of population (as of 2010)[234] |

|---|---|

| Spanish | 7.50% |

| Portuguese | 2.97% |

| Chinese (including Cantonese and Mandarin) | 1.59% |

| French (including New England French) | 1.11% |

| French Creole | 0.89% |

| Italian | 0.72% |

| Russian | 0.62% |

| Vietnamese | 0.58% |

| Greek | 0.41% |

| Arabic and Khmer (Cambodian) (including all Austroasiatic languages) (tied) | 0.37% |

As of 2010, 78.93% (4,823,127) of Massachusetts residents 5 and older spoke English at home as a first language, while 7.50% (458,256) spoke Spanish, 2.97% (181,437) Portuguese, 1.59% (96,690) Chinese (which includes Cantonese and Mandarin), 1.11% (67,788) French, 0.89% (54,456) French Creole, 0.72% (43,798) Italian, 0.62% (37,865) Russian, and Vietnamese was spoken as a primary language by 0.58% (35,283) of the population over 5. In total, 21.07% (1,287,419) of Massachusetts's population 5 and older spoke a first language other than English.[199][234]

Religion

[edit]Religious self-identification, per Public Religion Research Institute's 2022 American Values Survey[235]

Massachusetts was founded and settled by Brownist Puritans in 1620,[87] and soon after by other groups of Separatists/Dissenters, Nonconformists and Independents from 17th century England.[236] A majority of people in Massachusetts today remain Christians.[199] The descendants of the Puritans belong to many different churches; in the direct line of inheritance are the various Congregational churches, the United Church of Christ and congregations of the Unitarian Universalist Association. The headquarters of the Unitarian Universalist Association, long located on Beacon Hill, is now located in South Boston.[237][238] Many Puritan descendants also dispersed to other Protestant denominations. Some disaffiliated along with Roman Catholics and other Christian groups in the wake of modern secularization.[239]

As of the 2014 Pew study, Christians made up 57% of the state's population, with Protestants making up 21% of them. Roman Catholics made up 34% and now predominate because of massive immigration from primarily Catholic countries and regions—chiefly Ireland, Italy, Poland, Portugal, Quebec, and Latin America. Both Protestant and Roman Catholic communities have been in decline since the late 20th century, due to the rise of irreligion in New England. It is the most irreligious region of the country, along with the Western United States; for comparison and contrast however, in 2020, the Public Religion Research Institute determined 67% of the population were Christian reflecting a slight increase of religiosity.[240] A significant Jewish population immigrated to the Boston and Springfield areas between 1880 and 1920. Jews make up 3% of the population. Mary Baker Eddy made the Boston Mother Church of Christian Science serve as the world headquarters of this new religious movement. Buddhists, Pagans, Hindus, Seventh-day Adventists, Muslims, and Mormons may also be found. The Satanic Temple has its headquarters in Salem. Kripalu Center in Stockbridge, the Shaolin Meditation Temple in Springfield, and the Insight Meditation Center in Barre are examples of non-Abrahamic religious centers in Massachusetts. According to 2010 data from The Association of Religion Data Archives, (ARDA) the largest single denominations are the Catholic Church with 2,940,199 adherents; the United Church of Christ with 86,639 adherents; and the Episcopal Church with 81,999 adherents.[241]

In 2014, 32% of the population identified as having no religion;[242] in a separate 2020 study, 23% of the population identified as irreligious, and 67% of the population identified as Christians (including 26% as white Protestants and 20% as white Catholics).[240] As of 2022, a plurality of Massachusettsans were irreligious,[240] and the state is considered to be a part of the Unchurched Belt.[243]

Native American tribes

[edit]What is today Massachusetts was originally inhabited by the Wampanoag, the Nipmuc, the Massachusett, the Pocumtuc, the Nauset, the Pennacook and a few other tribes.[244][245] Some of these tribes are still represented among the population of the state today.

The largest Native American tribes in Massachusetts according to the 2010 census are listed in the table below:[246]

| Tribal grouping | American Indian and

Alaska Native alone |

AIAN in combination with

one or more other races |

Total AIAN alone or

in any combination |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total AIAN population | 18850 | 31855 | 50705 |

| Cherokee | 885 | 3654 | 4539 |

| Wampanoag | 1674 | 1642 | 3316 |

| Micmac | 623 | 1166 | 1789 |

| South American Indian | 817 | 930 | 1747 |

| Blackfeet | 298 | 1347 | 1645 |

| Mexican American Indian | 1131 | 449 | 1580 |

| Iroquois | 457 | 984 | 1441 |

| Central American Indian | 635 | 332 | 967 |

| Nipmuc | 305 | 550 | 855 |

| Abenaki | 197 | 469 | 666 |

| Sioux | 186 | 463 | 649 |

| Tribe not specified | 9421 | 16535 | 25956 |

Education

[edit]

In 2018, Massachusetts's overall educational system was ranked the top among all fifty U.S. states by U.S. News & World Report.[248] Massachusetts was the first state in North America to require municipalities to appoint a teacher or establish a grammar school with the passage of the Massachusetts Education Law of 1647,[249] and 19th century reforms pushed by Horace Mann laid much of the groundwork for contemporary universal public education[250][251] which was established in 1852.[128] Massachusetts is home to the oldest school in continuous existence in North America (The Roxbury Latin School, founded in 1645), as well as the country's oldest public elementary school (The Mather School, founded in 1639),[252] its oldest high school (Boston Latin School, founded in 1635),[253] its oldest continuously operating boarding school (The Governor's Academy, founded in 1763),[254] its oldest college (Harvard University, founded in 1636),[255] and its oldest women's college (Mount Holyoke College, founded in 1837).[256] Massachusetts is also home to the highest ranked private high school in the United States, Phillips Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, which was founded in 1778.[257]

Massachusetts's per-student public expenditure for elementary and secondary schools was eighth in the nation in 2012, at $14,844.[258] In 2013, Massachusetts scored highest of all the states in math and third-highest in reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress.[259] Massachusetts' public-school students place among the top tier in the world in academic performance.[67]

Massachusetts is home to 121 institutions of higher education.[260] Harvard University and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, both located in Cambridge, consistently rank among the world's best private universities and universities in general.[261] In addition to Harvard and MIT, several other Massachusetts universities rank in the top 50 at the undergraduate level nationally in the widely cited rankings of U.S. News & World Report: Tufts University (#27), Boston College (#32), Brandeis University (#34), Boston University (#37) and Northeastern University (#40). Massachusetts is also home to three of the top five U.S. News & World Report's best Liberal Arts Colleges: Williams College (#1), Amherst College (#2), and Wellesley College (#4).[262] It is also home to the oldest Catholic liberal arts college, College of the Holy Cross (#33).[263] Boston Architectural College is New England's largest private college of spatial design. The public University of Massachusetts (nicknamed UMass) features five campuses in the state, with its flagship campus in Amherst, which enrolls more than 25,000.[264][265]

As of 2021, Massachusetts has the highest percentage of adults over the age of 25 with a bachelor's degree (46.62%) and a graduate degree (21.27%) of any state in the country.

Economy

[edit]The United States Bureau of Economic Analysis estimates that the Massachusetts gross state product in 2020 was $584 billion.[266] The per capita personal income in 2012 was $53,221, making it the third-highest state in the nation.[267] As of January 2023, Massachusetts state general minimum wage is $15.00 per hour while the minimum wage for tipped workers is $6.75 an hour, with a guarantee that employers will pay the difference should a tipped employee's hourly wage not meet or exceed the general minimum wage.[268] This wage was set to increase to a general minimum of $15.00 per hour and a tipped worker minimum of $6.75 per hour in January 2023, as part of a series of minimum wage amendments passed in 2018 that saw the minimum wage increase slowly every January up to 2023.[269]

In 2015, twelve Fortune 500 companies were located in Massachusetts: Liberty Mutual, Massachusetts Mutual Life Insurance Company, TJX Companies, General Electric, Raytheon, American Tower, Global Partners, Thermo Fisher Scientific, State Street Corporation, Biogen, Eversource Energy, and Boston Scientific.[270] CNBC's list of "Top States for Business for 2023" has recognized Massachusetts as the 15th-best state in the nation for business,[271] and for the second year in a row in 2016 the state was ranked by Bloomberg as the most innovative state in America.[272] According to a 2013 study by Phoenix Marketing International, Massachusetts had the sixth-largest number of millionaires per capita in the United States, with a ratio of 6.73 percent.[273] Billionaires living in the state include past and present leaders (and related family) of local companies such as Fidelity Investments, New Balance, Kraft Group, Boston Scientific, and the former Continental Cablevision.[274]

Massachusetts has three foreign-trade zones, the Massachusetts Port Authority of Boston, the Port of New Bedford, and the City of Holyoke.[275] Boston-Logan International Airport is the busiest airport in New England, serving 33.4 million total passengers in 2015, and witnessing rapid growth in international air traffic since 2010.[276]

Sectors vital to the Massachusetts economy include higher education, biotechnology, information technology, finance, health care, tourism, manufacturing, and defense. The Route 128 corridor and Greater Boston continue to be a major center for venture capital investment,[277] and high technology remains an important sector. In recent years tourism has played an ever-important role in the state's economy, with Boston and Cape Cod being the leading destinations.[278] Other popular tourist destinations include Salem, Plymouth, and the Berkshires. Massachusetts is the sixth-most popular tourist destination for foreign travelers.[279] In 2010, the Great Places in Massachusetts Commission published '1,000 Great Places in Massachusetts' that identified 1,000 sites across the commonwealth to highlight the diverse historic, cultural, and natural attractions.[280]

While manufacturing comprised less than 10% of Massachusetts's gross state product in 2016, the Commonwealth ranked 16th in the nation in total manufacturing output in the United States.[281] This includes a diverse array of manufactured goods such as medical devices, paper goods, specialty chemicals and plastics, telecommunications and electronics equipment, and machined components.[282][283]

The more than 33,000 nonprofits in Massachusetts employ one-sixth of the state's workforce.[284] In 2007, Governor Deval Patrick signed into law a state holiday, Nonprofit Awareness Day.[285]

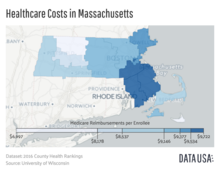

In February 2017, U.S. News & World Report ranked Massachusetts the best state in the United States based upon 60 metrics including healthcare, education, crime, infrastructure, opportunity, economy, and government. Massachusetts ranked number one in education, number two in healthcare, and number five in the handling of the economy.[286]

Agriculture

[edit]As of 2012, there were 7,755 farms in Massachusetts encompassing a total of 523,517 acres (2,120 km2), averaging 67.5 acres (27.3 hectares) apiece.[287] Greenhouse, floriculture, and sod products – including the ornamental market – make up more than one third of the state's agricultural output.[288][289] Particular agricultural products of note also include cranberries, sweet corn and apples are also large sectors of production.[289] Fruit cultivation is an important part of the state's agricultural revenues,[290] and Massachusetts is the second-largest cranberry-producing state after Wisconsin.[291]

Taxation

[edit]Depending on how it is calculated, state and local tax burden in Massachusetts has been estimated among U.S. states and Washington D.C. as 21st-highest (11.44% or $6,163 per year for a household with nationwide median income)[292] or 25th-highest overall with below-average corporate taxes (39th-highest), above-average personal income taxes, (13th-highest), above-average sales tax (18th-highest), and below-average property taxes (46th-highest).[293] In the 1970s, the Commonwealth ranked as a relatively high-tax state, gaining the pejorative nickname "Taxachusetts". This was followed by a round of tax limitations during the 1980s—a conservative period in American politics—including Proposition 2½.[294]

As of January 1, 2020, Massachusetts has a flat-rate personal income tax of 5.00%,[295] after a 2002 voter referendum to eventually lower the rate to 5.0%[296] as amended by the legislature.[297] There is a tax exemption for income below a threshold that varies from year to year. The corporate income tax rate is 8.8%,[298] and the short-term capital gains tax rate is 12%.[299] An unusual provision allows filers to voluntarily pay at the pre-referendum 5.85% income tax rate, which is done by between one and two thousand taxpayers per year.[300]

The state imposes a 6.25% sales tax[298] on retail sales of tangible personal property—except for groceries, clothing (up to $175.00), and periodicals.[301] The sales tax is charged on clothing that costs more than $175.00, for the amount exceeding $175.00.[301] Massachusetts also charges a use tax when goods are bought from other states and the vendor does not remit Massachusetts sales tax; taxpayers report and pay this on their income tax forms or dedicated forms, though there are "safe harbor" amounts that can be paid without tallying up actual purchases (except for purchases over $1,000).[301] There is no inheritance tax and limited Massachusetts estate tax related to federal estate tax collection.[299]

Energy

[edit]Massachusetts's electricity generation market was made competitive in 1998, enabling retail customers to change suppliers without changing utility companies.[302] In 2018, Massachusetts consumed 1,459 trillion BTU,[303] making it the seventh-lowest state in terms of consumption of energy per capita, and 31 percent of that energy came from natural gas.[303] In 2014 and 2015, Massachusetts was ranked as the most energy efficient state the United States[304][305] while Boston is the most efficient city,[306] but it had the fourth-highest average residential retail electricity prices of any state.[303] In 2018, renewable energy was about 7.2 percent of total energy consumed in the state, ranking 34th.[303]

Transportation

[edit]

Massachusetts has 10 regional metropolitan planning organizations and three non-metropolitan planning organizations covering the remainder of the state;[307] statewide planning is handled by the Massachusetts Department of Transportation. Transportation is the single largest source of greenhouse gas emissions by economic sector in Massachusetts.[308]

Regional public transportation

[edit]The Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority (MBTA), also known as "The T",[309] operates public transportation in the form of subway,[310] bus,[311] and ferry[312] systems in the Metro Boston area.

Fifteen other regional transit authorities provide public transportation in the form of bus services in the rest of the state.[313] Four heritage railways are also in operation:

- The Cape Cod Central Railroad, operating from Hyannis to Buzzards Bay[314]

- The Berkshire Scenic Railway, operating from Lee to Great Barrington[315]

- Edaville Railroad in Carver[316]

- The Lowell National Historical Park Trolley Line in Lowell[317]

Long-distance rail and bus

[edit]Amtrak operates several inter-city rail lines in Massachusetts. Boston's South Station serves as the terminus for three lines, namely the high-speed Acela Express, which links to cities such as Providence, New Haven, New York City, and eventually Washington DC; the Northeast Regional, which follows the same route but includes many more stops, and also continues further south to Newport News in Virginia; and the Lake Shore Limited, which runs westward to Worcester, Springfield, and eventually Chicago.[318][319] Boston's other major station, North Station, serves as the southern terminus for Amtrak's Downeaster, which connects to Portland and Brunswick in Maine.[318]

Outside of Boston, Amtrak connects several cities across Massachusetts, along the aforementioned Acela, Northeast Regional, Lake Shore Limited, and Downeaster lines, as well as other routes in central and western Massachusetts. The Amtrak Hartford Line connects Springfield to New Haven, operated in conjunction with the Connecticut Department of Transportation, and the Valley Flyer runs a similar route but continues further north to Greenfield. Several stations in western Massachusetts are also served by the Vermonter, which connects St. Albans, Vermont to Washington DC.[318]

Amtrak carries more passengers between Boston and New York than all airlines combined (about 54% of market share in 2012),[320] but service between other cities is less frequent. There, more frequent intercity service is provided by private bus carriers, including Peter Pan Bus Lines (headquartered in Springfield), Greyhound Lines, OurBus, BoltBus and Plymouth and Brockton Street Railway. Various Chinatown bus lines depart for New York from South Station in Boston.[321]

MBTA Commuter Rail services run throughout the larger Greater Boston area, including service to Worcester, Fitchburg, Haverhill, Newburyport, Lowell, and Kingston.[322] This overlaps with the service areas of neighboring regional transportation authorities. As of the summer of 2013 the Cape Cod Regional Transit Authority in collaboration with the MBTA and the Massachusetts Department of Transportation (MassDOT) is operating the CapeFLYER providing passenger rail service between Boston and Cape Cod.[323][324]

Ferry

[edit]Most ports north of Cape Cod are served by Boston Harbor Cruises, which operates ferry services in and around Greater Boston under contract with the Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority. Several routes connect the downtown area with Hingham, Hull, Winthrop, Salem, Logan Airport, Charlestown, and some of the islands located within the harbor. The same company also operates seasonal service between Boston and Provincetown.[325]

On the southern shore of the state, several different passenger ferry lines connect Martha's Vineyard to ports along the mainland, including Woods Hole, Hyannis, New Bedford, and Falmouth, all in Massachusetts, as well as North Kingstown in Rhode Island, Highlands in New Jersey, and New York City in New York.[326] Similarly, several different lines connect Nantucket to ports including Hyannis, New Bedford, Harwich, and New York City.[327] Service between the two islands is also offered. The dominant companies serving these routes include SeaStreak, Hy-Line Cruises, and The Steamship Authority, the latter of which regulates all passenger services in the region and is also the only company permitted to offer freight ferry services to the islands.[328]

Other ferry connections in the state include a water taxi connecting various points in Fall River,[329] seasonal ferry service connecting Plymouth to Provincetown,[330] and a service between New Bedford and Cuttyhunk.[331]

Rail freight

[edit]As of 2018, a number of freight railroads were operating in Massachusetts, with Class I railroad CSX being the largest carrier, and another Class 1, Norfolk Southern serving the state via its Pan Am Southern joint partnership. Several regional and short line railroads also provide service and connect with other railroads.[332] Massachusetts has a total of 1,110 miles (1,790 km) of freight trackage in operation.[333][334]

Air service

[edit]

Boston Logan International Airport served 33.5 million passengers in 2015 (up from 31.6 million in 2014)[276] through 103 gates.[335][336] Logan, Hanscom Field in Bedford, and Worcester Regional Airport are operated by Massport, an independent state transportation agency.[336] Massachusetts has 39 public-use airfields[337] and more than 200 private landing spots.[338] Some airports receive funding from the Aeronautics Division of the Massachusetts Department of Transportation and the Federal Aviation Administration; the FAA is also the primary regulator of Massachusetts air travel.[339]

Roads

[edit]

There are a total of 36,800 miles (59,200 km) of interstates and other highways in Massachusetts.[340] Interstate 90 (I-90, also known as the Massachusetts Turnpike), is the longest interstate in Massachusetts. The route travels 136 mi (219 km) generally west to east, entering Massachusetts at the New York state line in the town of West Stockbridge, and passes just north of Springfield, just south of Worcester and through Framingham before terminating near Logan International Airport in Boston.[341] Other major interstates include I-91, which travels generally north and south along the Connecticut River; I-93, which travels north and south through central Boston, then passes through Methuen before entering New Hampshire; and I-95, which connects Providence, Rhode Island with Greater Boston, forming a partial loop concurrent with Route 128 around the more urbanized areas before continuing north along the coast into New Hampshire.[342]

I-495 forms a wide loop around the outer edge of Greater Boston. Other major interstates in Massachusetts include I-291, I-391, I-84, I-195, I-395, I-290, and I-190. Major non-interstate highways in Massachusetts include U.S. Routes 1, 3, 6, and 20, and state routes 2, 3, 9, 24, and 128. A great majority of interstates in Massachusetts were constructed during the mid-20th century, and at times were controversial, particularly the intent to route I-95 northeastwards from Providence, Rhode Island, directly through central Boston, first proposed in 1948. Opposition to continued construction grew, and in 1970 Governor Francis W. Sargent issued a general prohibition on most further freeway construction within the I-95/Route 128 loop in the Boston area.[343] A massive undertaking to bring I-93 underground in downtown Boston, called the Big Dig, brought the city's highway system under public scrutiny for its high cost and construction quality.[140]

Government and politics

[edit]

Massachusetts has a long political history; earlier political structures included the Mayflower Compact of 1620, the separate Massachusetts Bay and Plymouth colonies, and the combined colonial Province of Massachusetts. The Massachusetts Constitution was ratified in 1780 while the Revolutionary War was in progress, four years after the Articles of Confederation was drafted, and eight years before the present United States Constitution was ratified on June 21, 1788. Drafted by John Adams, the Massachusetts Constitution is the oldest functioning written constitution in continuous effect in the world.[344][345][346] It has been amended 121 times, most recently in 2022.[347]

Massachusetts politics since the second half of the 20th century have generally been dominated by the Democratic Party, and the state has a reputation for being the most liberal state in the country.[348] In 1974, Elaine Noble became the first openly lesbian or gay candidate elected to a state legislature in US history.[349] The state's 12th congressional district elected the first openly gay member of the United States House of Representatives, Gerry Studds, in 1972[350] and in 2004, Massachusetts became the first state to allow same-sex marriage.[63] In 2006, Massachusetts became the first state to approve a law that provided for nearly universal healthcare.[351][352] Massachusetts has a pro-sanctuary city law.[353]

In a 2020 study, Massachusetts was ranked as the 11th easiest state for citizens to vote in.[354]

Government

[edit]

The Government of Massachusetts is divided into three branches: executive, legislative, and judicial. The governor of Massachusetts heads the executive branch, while legislative authority vests in a separate but coequal legislature. Meanwhile, judicial power is constitutionally guaranteed to the independent judicial branch.[355]

Executive branch

[edit]As chief executive, the governor is responsible for signing or vetoing legislation, filling judicial and agency appointments, granting pardons, preparing an annual budget, and commanding the Massachusetts National Guard.[356] Massachusetts governors, unlike those of most other states, are addressed as His/Her Excellency.[356] The governor is Maura Healey and the incumbent lieutenant governor is Kim Driscoll. The governor conducts the affairs of state alongside a separate Governor's Council made up of the lieutenant governor and eight separately elected councilors.[356] The council is charged by the state constitution with reviewing and confirming gubernatorial appointments and pardons, approving disbursements out of the state treasury, and certifying elections, among other duties.[356]

Aside from the governor and Governor's Council, the executive branch also includes four independently elected constitutional officers: a secretary of the commonwealth, an attorney general, a state treasurer, and a state auditor. The commonwealth's incumbent constitutional officers are respectively William F. Galvin, Andrea Campbell, Deb Goldberg and Diana DiZoglio, all Democrats. In accordance with state statute, the secretary of the commonwealth administers elections, regulates lobbyists and the securities industry, registers corporations, serves as register of deeds for the entire state, and preserves public records as keeper of the state seal.[357] Meanwhile, the attorney general provides legal services to state agencies, combats fraud and corruption, investigates and prosecutes crimes, and enforces consumer protection, environment, labor, and civil rights laws as Massachusetts chief lawyer and law enforcement officer.[358] At the same time, the state treasurer manages the state's cash flow, debt, and investments as chief financial officer, whereas the state auditor conducts audits, investigations, and studies as chief audit executive in order to promote government accountability and transparency and improve state agency financial management, legal compliance, and performance.[359][360]

Legislative branch

[edit]The Massachusetts House of Representatives and Massachusetts Senate comprise the legislature of Massachusetts, known as the Massachusetts General Court.[356] The House consists of 160 members while the Senate has 40 members.[356] Leaders of the House and Senate are chosen by the members of those bodies; the leader of the House is known as the Speaker while the leader of the Senate is known as the President.[356] Each branch consists of several committees.[356] Members of both bodies are elected to two-year terms.[361]

Judicial branch

[edit]The Massachusetts Supreme Judicial Court (a chief justice and six associates) are appointed by the governor and confirmed by the Governor's Council, as are all other judges in the state.[356]

Federal court cases are heard in the United States District Court for the District of Massachusetts, and appeals are heard by the United States Court of Appeals for the First Circuit.[362]

Federal representation

[edit]The Congressional delegation from Massachusetts is entirely Democratic.[363] The Senators are Elizabeth Warren and Ed Markey while the Representatives are Richard Neal (1st), Jim McGovern (2nd), Lori Trahan (3rd), Jake Auchincloss (4th), Katherine Clark (5th), Seth Moulton (6th), Ayanna Pressley (7th), Stephen Lynch (8th), and Bill Keating (9th).[364]

In U.S. presidential elections since 2012, Massachusetts has been allotted 11 votes in the electoral college, out of a total of 538.[365] Like most states, Massachusetts's electoral votes are granted in a winner-take-all system.[366]

Politics

[edit]

For more than 70 years, Massachusetts has shifted from a previously Republican-leaning state to one largely dominated by Democrats; the 1952 victory of John F. Kennedy over incumbent Senator Henry Cabot Lodge Jr. is seen as a watershed moment in this transformation. His younger brother Edward M. Kennedy held that seat until his death from a brain tumor in 2009.[367] Since the 1950s, Massachusetts has gained a reputation as being a politically liberal state and is often used as an archetype of modern liberalism, hence the phrase "Massachusetts liberal".[368]

Massachusetts is one of the most Democratic states in the country. Democratic core concentrations are everywhere, except for a handful of Republican leaning towns in the Central and Southern parts of the state. Until recently, Republicans were dominant in the Western and Northern suburbs of Boston, however both areas heavily swung Democratic in the Trump era. The state as a whole has not given its Electoral College votes to a Republican in a presidential election since Ronald Reagan carried it in 1984, and not a single county has voted for a Republican presidential candidate since 1988 . Additionally, Massachusetts provided Reagan with his smallest margins of victory in both the 1980[369] and 1984 elections.[370] Massachusetts had been the only state to vote for Democrat George McGovern in the 1972 presidential election. In 2020, Biden received 65.6% of the vote, the best performance in over 50 years for a Democrat.[371]

Democrats have an absolute grip on the Massachusetts congressional delegation; there are no Republicans elected to serve at the federal level. Both Senators and all nine Representatives are Democrats; only one Republican (former Senator Scott Brown) has been elected to either house of Congress from Massachusetts since 1994. Massachusetts is the most populous state to be represented in the United States Congress entirely by a single party.[372]

As of the 2018 elections, the Democratic Party holds a super-majority over the Republican Party in both chambers of the Massachusetts General Court (state legislature). Out of the state house's 160 seats, Democrats hold 127 seats (79%) compared to the Republican Party's 32 seats (20%), an independent sits in the remaining one,[373] and 37 out of the 40 seats in the state senate (92.5%) belong to the Democratic Party compared to the Republican Party's three seats (7.5%).[374] Both houses of the legislature have had Democratic majorities since the 1950s.[375]

| Party registration as of August 2024[376] | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Total voters | Percentage | |||

| Unenrolled | 3,256,754 | 64.43% | |||

| Democratic | 1,327,704 | 26.27% | |||

| Republican | 418,899 | 8.29% | |||

| Other | 51,182 | 1.01% | |||

| Total | 5,054,539 | 100.00% | |||

Despite the state's Democratic-leaning tendency, Massachusetts has generally elected Republicans as Governor: only two Democrats (Deval Patrick and Maura Healey) have served as governor since 1991, and among gubernatorial election results from 2002 to 2022, Republican nominees garnered 48.4% of the vote compared to 45.7% for Democratic nominees.[377] These have been considered to be among the most moderate Republican leaders in the nation;[378][379] they have received higher net favorability ratings from the state's Democrats than Republicans.[380]

A number of contemporary national political issues have been influenced by events in Massachusetts, such as the decision in 2003 by the state Supreme Judicial Court allowing same-sex marriage[381] and a 2006 bill which mandated health insurance for all Massachusetts residents.[352] In 2008, Massachusetts voters passed an initiative decriminalizing possession of small amounts of marijuana.[382] Voters in Massachusetts also approved a ballot measure in 2012 that legalized the medical use of marijuana.[383] Following the approval of a ballot question endorsing legalization in 2016, Massachusetts began issuing licenses for the regulated sale of recreational marijuana in June 2018. The licensed sale of recreational marijuana became legal on July 1, 2018; however, the lack of state-approved testing facilities prevented the sale of any product for several weeks.[384] However, in 2020, a ballot initiative to implement Ranked-Choice Voting failed, despite being championed by many progressives.[385]

Massachusetts is one of the most pro-choice states in the Union. A 2014 Pew Research Center poll found that 74% of Massachusetts residents supported the right to an abortion in all/most cases, making Massachusetts the most pro-choice state in the United States.[386]