David Wilkie Wynfield

David Wilkie Wynfield | |

|---|---|

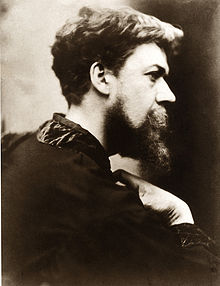

A self-portrait by Wynfield | |

| Born | c. 1837 |

| Died | 26 May 1887 (aged 49–50) |

| Nationality | British |

| Known for | Painting, photography |

David Wilkie Wynfield (c. 1837 – 26 May 1887) was a British painter and photographer who gained recognition for his historical genre paintings and his pioneering use of shallow-focus portrait photography.

He was a founding member of the St John's Wood Clique, a group of artists known for their historical narratives. He often used Medieval or Renaissance Europe as settings for his romantic themes in his paintings.

Although primarily a painter, Wynfield excelled in the practice of photography, with a style that imitated the painterly effects of Old Master artists. His work heavily influenced Julia Margaret Cameron, to whom he passed on his technique of shallow-focus portrait photography.

With a lack of press coverage of his work in his life, Wynfield's legacy was marginalized as a dilettante. His work has gained renewed interest in recent years due to the efforts of his descendants and his connection with Julia Margaret Cameron.

Early life[edit]

David Wilkie Wynfield was born in India[1] to a family of military background, with his father serving as an Indian Army officer.[1] As a child, he returned to England.

Despite his initial intention to become a clergyman,[2] Wynfield's interest in art flourished as a young man.[3] In 1856, he enrolled in James Mathew Leigh's art school, marking the beginning of his formal education in the field.[3]

Career[edit]

Wynfield exhibited his first painting at the Royal Academy in 1859[2] and joined the St. John's Wood Clique, a group of artists known for their historical narratives.[1] Wynfield's paintings often focused on romantic themes and were set in Medieval or Renaissance Europe.[1]

In the 1860s, Wynfield became interested in photography and developed a unique shallow-focus portrait photography technique.[4] He passed this technique on to Julia Margaret Cameron, who credited him as her main influence.[3]

Wynfield's photography often featured members of the St. John's Wood Clique and their friends in historical costumes. The images imitated the painterly effects of Old Master artists.[4][5] In 1864, his photographs were published in a book called The Studio: A Collection of Photographic Portraits of Living Artists, Taken in the Style of Old Masters, by an Amateur.[3] However, the publication of his photographs may have been unsuccessful as Wynfield withdrew them from circulation soon after.[1]

He continued to display his paintings in London exhibitions, particularly at the Royal Academy, until 1887.[2]

Promotion of contemporary art and artists[edit]

Wynfield supported contemporary art and artists in the late 19th century. He joined the committee of the Dudley Gallery in Piccadilly, London, in 1867 and encouraged marginalized artists to exhibit there. Wynfield made a series of photographs of contemporary artists in the 1860s and 1870s to publicise his contemporaries.[3]

During this period, the St John's Wood Clique aimed for popular success, while figures such as Whistler promoted the French notion that the artist should "épater le bourgeois." As a result, the paintings of the St John's Wood Clique were often seen as a contrast to more traditional types of artistic production.

However, this polarisation of artistic styles and schools did not account for the fashionable notion of the time that all artists were brothers. Wynfield vigorously promoted this view and believed that all artists, regardless of style or school, deserved equal recognition and support.[3]

Military service[edit]

Wynfield joined the 38th Middlesex regiment of the Artists' volunteer rifles, a volunteer corps formed in 1859–60 due to the perceived French invasion threat. Unlike his peers, he remained committed to the corps and eventually rose to the rank of captain of H company in 1880.

Wynfield's photographs, including two self-portraits, convey the idea that military and scholarly life can coexist, reflecting a humanist philosophy from the medieval period. Wynfield's interestin genealogy and heraldry influenced this philosophy.[3]

Personal life[edit]

Wynfield resided with his mother, while his sister Anne and her husband moved to the same street in 1865. He remained unmarried throughout his life.

Wynfield passed away on 26 May 1887 due to tuberculosis and was interred at Highgate Cemetery.

Paintings[edit]

Wynfield specialized in a style of art commonly referred to as 'historical genre', characterized by depictions of historical, domestic, or romantic events from medieval and Renaissance periods.[4]

One of Wynfield's most renowned works is The Death of Buckingham, which was displayed in 1871 at the Royal Academy.[4]

In the late 1860s, the artist began producing works that alternated between serious and lighthearted themes, with tragedy frequently featuring in his paintings.[3]

Photography style and technique[edit]

Wynfield was primarily a painter, but also excelled in photography.[4] He rejected the conventions of mainstream Victorian photography and instead used painterly and experimental techniques, such as close-up views, soft focus, and strong contrasts of light and shade.[1] His portraits combined "painterly sfumato with photographic immediacy" due to his use of a close-up format and narrow depth of field.[3][4] Wynfield intentionally blurred the outline of his large-scale head studies by not focusing his camera exactly.[4]

While some critics viewed the soft focus of his photographs as indicative of amateurism, others praised their painterly quality.[1] His work heavily influenced Julia Margaret Cameron, whom he advised starting in 1864.[4]

Wynfield's photographic studies implicitly identified contemporary artists who sat for him as equal to their distinguished forebears. In his portraits, he often used the sepia tonality of Van Dyck's engraved Iconographie, a series of graphic portraits of artists, patrons, soldiers, and statesmen.[4] The costume and heightened chiaroscuro in his photographic studies further highlighted the similarities between his contemporary subjects and their illustrious predecessors.[3]

Legacy[edit]

Wynfield's portraits are displayed in various museums, including the National Portrait Gallery in London and the Victoria and Albert Museum.[4] Julia Margaret Cameron acknowledged him as the most significant influence on her work.[1]

His activities as a photographer have gained slightly more attention in recent years, thanks to his connection with Julia Margaret Cameron and the efforts of his descendants to revive his reputation.

Gallery[edit]

-

Portrait of an unknown man in armour.

-

Portrait of the painter Frederic Leighton in Renaissance costume.

-

Portrait of William Swinden Barber in Medieval costume.

-

Portrait of the painter George Frederic Watts.

-

Portrait of Alphonse Legros.

-

Portrait of the painter Simeon Solomon in oriental costume.

-

Portrait of the painter Valentine Cameron Prinsep, ca. 1860s

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h "David Wilkie Wynfield". Royal Academy of Arts. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c "Wynfield, David Wilkie". Benezit Dictionary of Artists. 2011. doi:10.1093/benz/9780199773787.article.b00199642. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Hacking, Juliet (2004). "Wynfield, David Wilkie". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/73438. Retrieved 15 February 2023. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j "Victorian artists: photographs by David Wilkie Wynfield, 1860s". National Portrait Gallery. Retrieved 15 February 2023.

- ^ Hacking, Juliet, Princes of Victorian Bohemia: Photographs by David Wilkie Wynfield, NPG, 2000.

- 19th-century British painters

- British people in colonial India

- British male painters

- 19th-century English photographers

- Artists' Rifles officers

- 1830s births

- 1887 deaths

- Burials at Highgate Cemetery

- 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- 19th-century English male artists

- Photographers from London

- Tuberculosis deaths in the United Kingdom

- 19th-century British Army personnel

- Volunteer Force officers

- Military personnel of British India