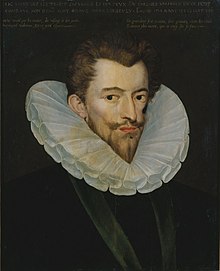

Claude de Bauffremont

Claude de Bauffremont | |

|---|---|

| baron de Sennecey | |

Coat of arms of Bauffremont | |

| Born | c. 1546 |

| Died | c. 1596 |

| Noble family | Maison de Bauffremont |

| Father | Nicolas de Bauffremont |

| Mother | Denise Patarin |

Claude de Bauffremont, baron de Sennecey (c. 1546–c. 1596)[1] was a French noble, governor, military commander and courtier during the latter French Wars of Religion. Born in 1546 into one of the most prominent noble families of Bourgogne, he was the son of Nicolas de Bauffremont and Denise Patarin. He acquired the roles of gentilhomme de la chambre du roi (gentleman of the king's chamber), bailli (bailliff) of Chalon-sur-Saône and second captain of the company of the duc de Guise (duke of Guise). As a client of the Guise, upon the death of the king's brother Alençon in 1584, he was among the founders of the second Catholic Ligue (League) that opposed the prospect of the king's distant Protestant cousin the king of Navarre ascending to the throne upon Henri's death. However, in the war between the ligue and the crown in 1585, Sennecey claimed illness, and remained largely inactive. He would play an important role in the negotiations between the crown and ligue that brought about the very favourable Treaty of Nemours in July of that year, in which Henri capitulated to the ligue and outlawed Protestantism.

In November of that year, the people of Auxonne overthrew their ligueur governor Jean de Saulx. Sennecey was tasked with bringing Guise's protests about the situation to Henri, and made a good impression on the king, and was likewise impressed by Henri's attitude to the situation. Henri decided to establish Sennecey as governor to replaced Saulx, who was clearly unacceptable to the population. The leaders of Auxonne refused to accept another ligueur (leaguer) like Sennecey either however, and a stand off of several months followed until Sennecey was established as governor of Auxonne in August. Auxonne was a key strategic border city and its control was keenly desired by Sennecey's patron the duc de Guise. In 1588 Sennecey served as speaker for the nobility at the Estates General of 1588 and in the civil war that engulfed the kingdom following Henri's decision to assassinate the duc de Guise in December, Sennecey fought with the ligue around the Lyonnais. The new leader of the ligue the duc de Mayenne, brother to the deceased duc de Guise had a disagreement with the lieutenant-general of his government of Bourgogne, and had him arrested. He selected Sennecey as his replacement. Sennecey was not however a reliable ligueur and entertained discussions with the Protestant Navarre, who now styled himself Henri IV on the death of Henri III. From late 1594 he prepared to defect, and secured not only the preservation of his governorship of Auxonne, but also the lieutenant-generalcy of Bourgogne. He died in 1596 and was succeeded by his brother.

Early life and family[edit]

Claude de Bauffremont was born in 1546, the son of Nicolas de Bauffremont and Denise Patarin.[2]

The Bauffremont were an ancient noble family of Lorraine.[2] In the sixteenth century they were among the most senior of the noblesse seconde (secondary nobility) of Bourgogne in the estimation of the historian Henri Drouot, alongside the families the Saulx-Tavannes and Chabot-Charny.[3] Claude's father was the speaker for the nobility at the Estates General of 1576. During this meeting he advocated for avoiding a civil war in favour of enforcing religious unity.[4] Meanwhile, Denise's father, Claude Patarin was the chancellor of the Ducato di Milano (duchy of Milano) and premier président of the Dijon Parlement.[2]

Another Bauffremont also named Claude served as the Bishop of Troyes from 1562.[2] He was the only bishop to involve himself in the St. Bartholomew's Day massacre in 1572.[5]

In 1571 Sennecey married Marie de Brichanteau, sister of the royal favourite Beauvais-Nangis.[6]

Through his life Sennecey was afflicted with gout, and leg pains.[7]

Reign of Henri III[edit]

Sennecey was the governor of Chalon-sur-Saône.[8] He held the position of gentilhomme de la chambre du roi in the court of Henri.[9] Sennecey served as the second captain of the duc de Guise's company of men-at-arms.[8]

Alençon[edit]

In 1581, the duc d'Alençon (brother of king Henri) had established himself as king in Nederland. To support his position in his kingdom he required the raising of troops in France. To this end he requested of Sennecey that three companies of light horse be raised from Champagne. In May, the lieutenant-general of Champagne wrote to Sennecey forbidding him from providing the troops to Alençon. Sennecey therefore dispersed the troops he had raised in July, and was greeted by a furious letter from Alençon, and a congratulatory missive from Henri.[10][11]

After his disgrace in 1582, the royal favourite Beauvais-Nangis looked for a new network of allies. He turned to La Châtre, and his brothers-in-law Vitry and Sennecey, finding them all united in purpose with him in their shared hatred of the arch-favourite Épernon.[12]

Ligue crisis[edit]

In June 1584, Henri's brother the duc d'Alençon died. As Henri had no children, the heir to the throne according to salic law became Henri's distant cousin the Protestant king of Navarre. This was seized upon as unacceptable by a segment of the Catholic nobility, chief among them the duc de Guise. In September, three months after the duc d'Alençons death, Guise his brother the duc de Mayenne, his other brother the Cardinal de Guise, the Norman noble the seigneur de Maineville and Sennecey met at Nancy and agreed to form a Catholic Ligue (League) to oppose the succession of Navarre, and a series of other royal policies they disapproved of. They agreed the Catholic faith was to be protected, while Protestantism would be expunged from the kingdom.[13] Maineville acted as the representative for their alternate candidate to succeed Henri III, the Cardinal de Bourbon (who would reign as Charles X).[14][15][16]

Sennecey and the baron de Rosne succeeded in seducing Beauvais-Nangis into being a partisan of the duc de Guise and the Catholic ligue. They accomplished this by letting Beauvais-Nangis know, that if he were to defect in his allegiance, Guise would reward him when he was ascendant with the post of colonel-general of the infantry.[17] Their coup would be a short term one, Beauvais-Nangis, upon realising that their promise Guise would provide the office of colonel-general would not come to pass, quickly retreated into political neutrality.[18]

War with the crown[edit]

The ligue of which Sennecey was a member entered civil war with the crown in March 1585.[19] Sennecey himself would not be particularly involved in the fighting, on the grounds of an alleged 'sickness'. The historian Niepce believes this may reflect a caution Sennecey felt towards the ambitions of the ligueur princes and desire to wait and see how the situation developed.[7] After several months of inconclusive fighting, the crown capitulated to the demands of the ligue in the Peace of Nemours.[20] The baron de Sennecey served as a negotiator between the crown and the duc de Guise in the attempts to reach this peace through the summer of 1585.[21]

Crisis of the ligue in Bourgogne[edit]

Sennecey's brother, the comte de Cruzille (count of Cruzille), another ally of the Guise, was governor of Mâcon, and in late 1585 he was ousted from his governate by the population. The citadel of Mâcon was demolished and Cruzille temporarily imprisoned.[22]

Auxonne[edit]

The city of Auxonne in Bourgogne had great strategic value, offering a strong defence against Spanish and other foreign efforts to invade France. It also held symbolic value as a testament to France's victory over the duché de Bourgogne in the fifteenth century. With peace between the ligue and crown the Protestant forces were re-arming in preparation for a new campaign against them, and to this end were likely to be requesting the support of German reiters. [23]

The ligueur governor of Auxonne, Jean de Saulx found himself overthrown in a coup on 1 November.[24] He was a client of the Guise and therefore the duc de Guise sought to protest against this development to the king. Indeed, some suspected the involvement of Henri in the coup.[25] Guise instructed Sennecey to travel to the court and present his grievances with developments in Bourgogne (at both Auxonne and Mâcon). Sennecey arrived on 8 November 1585. He quickly liaised with Catherine de Lorraine (the duc de Guise's sister) as to how to proceed. She informed Sennecey that she had already spoken with the king who had assured her of his good favour towards the Guise.[26] Further, Henri had told her he was keen to maintain one of the 'keys to the kingdom' (by which he meant Auxonne) in the hands of the Guise.[27]

Sennecey informed Guise that he was content with the reception that Catherine had received, and felt that it met the needs of his diplomatic mission.[27] The king wrote to Mayenne, who was campaigning against the Protestants in Guyenne, assuring him of his goodwill towards the house of Lorraine. He informed Mayenne that while he could not reinstall Jean de Saulx as governor, due to the overwhelming opposition to him in the population, he would select another of Mayenne's confidents.[28]

The next day Sennecey enjoyed a personal audience with the king which reinforced the opinions he had received from Catherine de Lorraine as to Henri's favour towards the Guise. Henri let it be known he was keen to see Auxonne preserved in the orbit of the Guise. He added however that Guise must renounce any efforts to assist Jean de Saulx in returning to his charge, as it was necessary this man be put on trial for his various corrupt dealings. Sennecey was satisfied with this, believing the duc de Guise's critiques had been satisfactorily addressed.[28]

It seemed Sennecey did not much care of Jean de Saulx was deprived of his office. This can be explained by the fact that Catherine de Lorraine had recommended Sennecey to take command of Auxonne on at least a temporary basis pending a decision on who to replace the disgraced governor by Mayenne.[29]

Governor of Auxonne[edit]

Guise continued to advocate for the re-establishment of the former governor, however in December Henri announced his intention to see the appointed of Sennecey to fill the office of governor of Auxonne in a letter to the inhabitants of the city. Sennecey rushed to the court to receive this appointment, meanwhile in Auxonne Léonor Chabot, comte de Charny the lieutenant-general of Bourgogne was put in temporary command. To allow for a smooth transition of command to Sennecey, Henri amnestied many of the coup participants in Auxonne for their actions against their former governor.[30]

Struggle for Auxonne[edit]

In Auxonne, the captain of the château the sieur de Pluvault was ascendent, his opinion was key in the decision of Auxonne to disobey Henri's commands.[31] On 29 December, the comte de Charny arrived in front of Auxonne and his messenger entered the city. Pluvault and the inhabitants had already met to discuss the prospect of Sennecey acquiring Auxonne. It was agreed that they would resist the appointment of Sennecey, and moreover that they would provide funds to Pluvault to raise soldiers. Charny expressed his frustration that Auxonne had chosen this path.[32] In an appeal to the king, the people of Auxonne protested that they wished to be subordinate to the crown and not a ligueur (leaguer) like Sennecey.[32]

In the following months, Pluvault held a secret audience with an advisor to the Protestant prince de Condé. These discussions were seized upon by Jean de Saulx who denounced the leaders of Auxonne as entering the Protestant camp. For the king and ligueur princes, these dealings forced them to moderate their plans to remove Pluvault by force and look to persuade him to stand down instead.[33]

Sennecey remained invested in the affairs of Auxonne during this period.[33] He was fearful the resolution of the conflict between the ligueur princes and Pluvault could end disfavourably for his interests, and therefore instructed a gentleman (Jean de Boyer, sieur de Chanlecy) who was liaising between Guise and Pluvault to keep him informed of developments.[34] Pluvault justified himself to the representative of Guise sent to negotiate with him that the inhabitants of Auxonne were entirely opposed to Sennecey, so he could not therefore persuade them to allow the admission of the new governor.[35]

In January the sieur de La Croisette, uncle of Pluvault, attempted to bring Auxonne over to Sennecey, but his effort was a failure.[36] By February, it was clear that Pluvault could not be talked down, and Guise turned towards the possibilities of force to establish Sennecey. A few days earlier, Jean de Saulx had escaped from the captivity he had been placed in by means of a rope, and he therefore found himself in a position to put pressure on Guise.[37] Saulx also undertook an attempt on Auxonne himself, which failed, and led to a burst of recruitment for Auxonne's defences.[38] Guise met with the king in March, and attempted to discuss the matters of Auxonne and Angers, both of which had thrown off their Guisard clients (in Angers - the comte de Brissac). He failed to convince the king, only being granted a single audience with him, but let it be known he was looking out for his clients.[36]

La Croisette was sent out again to receive the submission of Auxonne, but the city demanded that in return for doing so that no supporters of the ligue be permitted entry into the city. La Croisette refused to accede to this, and therefore on 17 April Auxonne again refused to submit.[39]

Siege of Auxonne[edit]

At this point the king informed Guise that he was willing to use force to see Sennecey installed. The comte de Charny was dispatched to give one final offer of submission to Auxonne in mid May 1586, however the king was by this point somewhat two faced, and though the city was threatened with being declared guilty of lèse majestė, the baron de Lux also informed those he was entreating with that the king wished for them to continue resisting.[40] Auxonne was already undertaking a significant recruitment of soldiers, and efforts to improve the fortification of the château had been began in early 1586.[38]

Sennecey learned in early June, that it was the intention of the comte de Charny, lieutenant-general of Bourgogne to install not himself (Sennecey) as governor, but rather his own brother the sieur de Brion. Sennecey stepped up his efforts to push Guise to lead a reduction of Auxonne upon learning this.[41] On 17 July the forces of Guise's lieutenants Jean de Saulx, Chrétien de Savigny, the baron de Rosne and Antoine de Saint-Paul put Auxonne under blockade. They lacked the numbers for a full siege but aimed to block any further reinforcements arriving.[41] Guise for his part raised forces in Lorraine with the support of the duc de Lorraine, and despatched Sennecey to request more aid from Henri.[42] Instead of providing more forces directly, Henri authorised the comte de Charny to undertake a siege instead. With his forces, and those of the duc d'Elbeuf, a siege could at last be undertaken.[43] Charny was to bring his landsknechts and some insufficient artillery to bear on Auxonne.[44]

Ultimately the city would be reduced, not by siege guns but rather composition. On 10 August a conference was undertaken at Tillenay, led by the Parlement président Pierre Jeannin. Mayenne hoped that Jeannin could prevent his brother from leading the negotiations and avoid military conflagration engulfing his governate.[45] It was agreed that Pluvault would be bought off, and an abbey granted to his son, meanwhile Auxonne itself would be granted 12,000 écus (crowns) to compensate them for damages done and exempted from taxes for 9 years.[46] In return for these various concessions Auxonne undertook to respect the installation of Sennecey as governor.[47]

While this agreement was generous to Pluvault, contemporaries believed Guise had little method by which to undertake an effective siege and it was cheaper for him to take a victory that allowed the installation of one of his clients. He further showed himself as a good servant of the king in respecting the decisions undertaken by Henri in December.[48]

Guise entered Auxonne in force, with 150 horse and visited the château d'Auxonne, two days after this visit he established Sennecey as the new governor of the city on 24 August 1586. Sennecey offered Guise the advantage of diluting his brothers authority in his governate.[49][21]

Between two parties[edit]

Sennecey occupied a strong position in Bourgogne, and inspired confidence.[50] Despite his proximity to the duc de Guise he maintained lines of communication with king Henri. A testament to this was his place as a member of the conseil privé (privy council) sometime before 1588.[9]

New war with the crown[edit]

At the Estates General of 1588, Sennecey served as the speaker for the second estate (nobility), just as his father had done at the Estates General of 1576. The three orders agreed to swear to uphold the Edict of Union alongside the king.[9] In December, with tensions at the Estates escalating between Guise and Henri, Henri resolved that the only course of action to take was to assassinate the duc de Guise, this accomplished on 24 December 1588 a new war between the crown and the ligue was brought about with the ligue seizing many cities across France, including Paris, and establishing the duc de Mayenne as their lieutenant-general of the kingdom.[51][52][53][54]

In early 1589 Sennecey took up residence in the hôtel de Guise in Paris, the building acting like a mini fortress in the city.[8]

With open civil war with the crown, Mayenne acted as a sovereign power in his governate of Bourgogne. He presented the ligueur Articles of Union to the Parlement of Dijon in March without even mentioning the authority of Henri. He instructed his lieutenant-general in the province Fervaques to use the troops he was dispatching from Paris to 'cleanse the province of vermin', by which he meant enemies of the ligue, be they Protestant or royalist.[55]

Fervaques would prove a poor choice, and he frustrated Mayenne by refusing to swear the oath to the ligue himself, declaring that he was a faithful servant of the king. Mayenne responded by having Fervaques locked in a château. To replace him as a more reliable lieutenant-general of Bourgogne, Mayenne turned to Sennecey. His appointment of Sennecey pre-empted any royal replacement of Fervaques.[55]

Reign of Henri IV[edit]

Sennecey was renowned for his caution, and acquired the nickname 'Fabius'.[50] He would prove no more reliable than Fervaques had been.[55] Indeed, he informed the Protestant Navarre, now styled Henri IV after the assassination of Henri III, that he had great loyalty to the deceased king. He was rewarded for this by Henri with the granting of the Abbey of Tournus.[9]

Despite this, he fought around Lyon for the ligue, and was involved in the capture of the future Marshal Ornano.[9]

Sennecey found himself caught up in the rivalry between the ligueur duc de Nemours and Nemours' nominal ally Mayenne. In pursuit of his rivalry with Mayenne, and as revenge for Mayenne's interference in the affairs of the Lyonnais, Nemours oversaw Sennecey's arrest in August 1591.[50]

On occasion Sennecey agreed to conduct 'harvest truces', which proved very popular.[9]

Loyalist[edit]

In 1593 he was entrusted by Mayenne with conducting an embassy to Roma, however he returned with little to show for his efforts. Seeing which way the wind was blowing by late 1594, he refused to hand over his governate of Auxonne to Mayenne and entered talks with Henri for his submission in early 1595. In April of that year Auxonne made its submission to Henri, and Sennecey secured the continuity of his governorship of the city.[9]

By December 1595, Sennecey had secured the continuity of his position as lieutenant-general of Bourgogne from Henri. He died in 1596 and was succeeded by his brother the comte de Cruzille.[9]

Sources[edit]

- Baumgartner, Frederic (1986). Change and Continuity in the French Episcopate: The Bishops and the Wars of Religion 1547-1610.

- Bourquin, Laurent (1994). Noblesse Seconde et Pouvoir en Champagne aux XVIe et XVIIe Siècles. Éditions de la Sorbonne.

- Carroll, Stuart (2011). Martyrs and Murderers: The Guise Family and the Making of Europe. Oxford University Press.

- Chevallier, Pierre (1985). Henri III: Roi Shakespearien. Fayard.

- Cloulas, Ivan (1979). Catherine de Médicis. Fayard.

- Constant, Jean-Marie (1984). Les Guise. Hachette.

- Constant, Jean-Marie (1996). La Ligue. Fayard.

- Holt, Mack (2002). The Duke of Anjou and the Politique Struggle During the Wars of Religion. Cambridge University Press.

- Holt, Mack P. (2020). The Politics of Wine in Early Modern France: Religion and Popular Culture in Burgundy, 1477-1630. Cambridge University Press.

- Jouanna, Arlette (1998). Histoire et Dictionnaire des Guerres de Religion. Bouquins.

- Knecht, Robert (2010). The French Wars of Religion, 1559-1598. Routledge.

- Knecht, Robert (2016). Hero or Tyrant? Henry III, King of France, 1574-1589. Routledge.

- Le Person, Xavier (2002). «Practiques» et «practiqueurs»: la vie politique à la fin du règne de Henri III (1584-1589). Librairie Droz.

- Roberts, Penny (1996). A City in Conflict: Troyes during the French Wars of Religion. Manchester University Press.

- Le Roux, Nicolas (2000). La Faveur du Roi: Mignons et Courtisans au Temps des Derniers Valois. Champ Vallon.

- Salmon, J.H.M (1979). Society in Crisis: France during the Sixteenth Century. Metheun & Co.

References[edit]

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 1482.

- ^ a b c d Jouanna 1998, p. 701.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 437.

- ^ Holt 2002, p. 80.

- ^ Baumgartner 1986, p. 152.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 430.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 464.

- ^ a b c Le Roux 2000, p. 289.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Jouanna 1998, p. 703.

- ^ Bourquin 1994, p. 117.

- ^ Jouanna 1998, p. 1248.

- ^ Le Roux 2000, p. 432.

- ^ Chevallier 1985, p. 563.

- ^ Cloulas 1979, p. 494.

- ^ Knecht 2016, pp. 229–231.

- ^ Constant 1996, p. 112.

- ^ Constant 1984, p. 122.

- ^ Constant 1996, p. 342.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 233.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 236.

- ^ a b Jouanna 1998, p. 702.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 457.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 463.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 446.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 462.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 459.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 460.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 461.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 465.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 478.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 481.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 482.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 488.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 489.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 491.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 499.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 492.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 508.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 500.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 503.

- ^ a b Le Person 2002, p. 509.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 513.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 514.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 515.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 517.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 518.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 519.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 520.

- ^ Le Person 2002, p. 415.

- ^ a b c Salmon 1979, p. 265.

- ^ Knecht 2016, p. 266.

- ^ Roberts 1996, p. 174.

- ^ Carroll 2011, p. 289.

- ^ Knecht 2010, p. 72.

- ^ a b c Holt 2020, p. 173.