Carlo Ponti (photographer)

Carlo Ponti (c. 1823–1893) was a Swiss-born optician and photographer active in Venice from about 1848.[1][2]

Early life[edit]

Carlo Ponti was born in Sagno in Canton Ticino, Switzerland between 1822 and 1824.[3] He moved as an adult to Paris to train for about five years in the workshop of optician Robert-Aglaé Cauchoix,before settling in Venice after 1848.

Career[edit]

Ponti opened an optician’s shop in Piazza San Marco 52,[4][5] near the Caffè Florian,[6] producing high quality instruments, for which he had sole rights, for astronomy and physics and photographic lenses, especially those used for panoramas, as well as selling products of other companies.[3] On 30 May 1854 he was awarded a silver medal for his photographic equipment at the Esposizione Industriale Veneta.

As a photographer and editor Ponti published photographic prints, both his own and others, building an international clientele. From this time he systematically photographed Venice and by 1855 had a catalogue of 160 photographic views of Venetian architecture (Guida fotografica illustrata della città di Venezia), each captioned with historical and aesthetic information, supported by an introductory history of Venetian architecture, which was awarded at the Universal Exhibition in Paris in 1855. He published and distributed postcards, stereographs and travel photographs of Venice and its art and architecture on an industrial scale, issuing thousands of prints a month made by hundreds of employees. Tourists' collections of such photographic spolia were preserved in their own photographic albums, and such distribution popularised classical and Italian Renaissance and Baroque art.[3]

In this industry he collaborated with Francesco Maria Zinelli and Giuseppe Beniamino Coen and provided an outlet for other studio operators such as Antonio Perini, Carlo Naya, and Domenico Bresolin who, on attaining the chair in landscape at the Accademia, transferred his studio and archive to Ponti.[3]

Ponti distributed their work with his own stamp, so that attribution is often in contention; Perini was probably the author of some of the photographs in the catalogue Ponti presented at the Exposition Universelle in Paris in 1855. Some prints in the Eastman House collection formerly attributed to Ponti were found to be marked with numbers corresponding to Naya's catalogues published between 1864 and his death in 1882.[7]

In 1866 Carlo Ponti became official photographer to King Victor Emanuel II of Italy, when Venice was incorporated in the Italian nation. The prestige of his royal appointment brought further business in other cities including Paris, London, Liverpool, Berlin, Stuttgart, Lyons, New York, Chicago, Philadelphia, Boston, Montreal, and San Francisco.[3]

Inventor[edit]

Ponti was an inventor of a sophisticated version of the peep show, the alethoscope (from the Greek “true”, “exact” and “vision”) in 1860 which he presented to the Société française de photographie in 1861, then in April, to the Istituto di Scienze, Lettere ed Arti in Venice, earning an honourable mention there in May.[8] He obtained a patent in January 1862 and commenced marketing it.

A larger version, the megalethoscope,[9] was produced for him by cabinetmaker Demetrio Puppolin, whose name is inscribed on different models, some highly decorated with pearl inlay and marquetry. His invention was awarded Grand Prix at the International Exhibition in London in 1862.[10]

Both devices enlarged photographic views through a wide, thick magnifying lens to create an illusion of the subjects' plasticity, perspective depth and modelling.[1][11] The albumen plates for some versions of the megalethoscope are curved with slotted wooden braces for optical correction of lens aberrations,[12] and pinprick perforations and mechanically thinned areas on the albumen prints have been made for viewing the photographic images under reflected and transmitted light to suggest day or night lighting, fantastic effects (diavoletti) and to add colours.[13][14]

This degree of animation of megalethoscope views was applied to the representaiton of events, and as a way to re-enact history, such as a daylight view of an empty St Mark's Square that could be transformed with back lighting into a night scene showing illuminations and lively crowds celebrating of the annexation of the Veneto by the rest of Italy. Another of the transparencies shows the burning of the Hôtel de Ville, Paris during the Paris Commune. Sets of images take the viewer on a simulated trip along the Grand Canal at night, a popular Venetian tourist experience. Ponti's success benefitted from his familiarity with, and repetition of, traditional painted views, and his distribution network through commercial studios beyond Venice, including that of Francis Frith in the United Kingdom and Pompeo Pozzi in Milan.[6]

Ponti's rights to these devices lapsed after 1866, due to administrative confusion after the after the Third Italian War of Independence, when Venice, along with the rest of the Veneto, became part of the newly created Kingdom of Italy. Despite Ponte's legal battles between 1868 and 1876 to prevent it, Carlo Naya began to manufacture and sell the Aletoscopio, which Ponti tried to counter by issuing variations of the instrument under other names including Amfoteroscopio, Dioramoscopio, Pontioscopio, Cosmorama Fotografico.[3] Well aware of their market value, Naya counter-sued Ponti for the many views that he had taken and were sold with Ponti's megalethoscope, though many were actually taken by Naya's assistants.

Later life[edit]

Ponti retained his Swiss citizenship throughout his life, but remained in Venice. He published catalogues of his images of Venice, but also of other Italian cities, in 1855, 1864, 1866 and 1872.[15] He became totally blind during his latter years, and died in Venice on 16 November 1893.

Exhibitions[edit]

- 1855: Exposition Universelle, Paris

Posthumous[edit]

- 1979: Fotografia italiana dell'Ottocento. Florence[15]

- 1980: Fotografia italiana dell'Ottocento. Venice[15]

- 1994, 23 September: Italien: Sehen und Sterben: Photographien zer Zeit des Risorgimento (1845-1870) exhibition organised by Agfa Foto-Historama. Römisch-Germanisches Museum, Köln[16]

- 1995, 2 March–5 June: Italien: Sehen und Sterben: Photographien zer Zeit des Risorgimento (1845-1870). Reiss-Museum der Stadt Mannheim[16]

- 1996, 31 October—2 February 1997: Un Magicien De L'image = Zauberkünstler Mit Bildern. Musée Suisse De L'appareil Photographique[17]

Collections[edit]

- Museé Suisse de l’Appareil Photographique, Vevey: an example of the Megaletoscopio and albumen prints[3][18]

- Fototeca della Soprintendenza per il Patrimonio Storico, Artistico e Demoetnoantropologico, Brera, Milan[3]

- Museo Nazionale Alinari della Fotografia[3]

- Dietmar Siegert Collection, Münich[3][19]

- Wilfried Wiegand Collection, Frankfurt am Main[3]

- Janos Scholz Collection[20]

- Department of Photography, J. Paul Getty Museum, Malibu[21]

- Musée D'Orsay[22]

- George Eastman House[23]

- Carlo Montanaro Archive[24]

Gallery[edit]

-

Carlo Ponti, 1860s, Venice, Stereograph on card

-

Ponti, Carlo (ca. 1860s) - Venezia - Palazzo Ducale - Dettaglio. Stereograph

-

Carlo Ponti 1870s Bridge of Sighs

-

Carlo Ponti, ca. 1870, Grand Canal: Palace Tiepolo Palais Tiepolo, Pont de Rialto. Venise. Albumen silver print with tissue and applied color (Megalethoscope slide)

-

Transparency attributed to Carlo Ponti. Interlaken, Switzerland ca. 1870. Albumen silver print with tissue and applied color (Megalethoscope slide). Image: 25.5 x 33.6 cm

-

Carlo Ponti (attributed to) Egypt Gizeh - The Three Pyramids ca. 1875. Albumen silver print with tissue and applied color (Megalethoscope slide) 24.8 x 33.8 cm.

-

Ponti, Carlo (ca. 1870s) - Venezia - Palazzo Ducale, cortile, albumen print

-

Ponti, Carlo (ca. 1870s) - Venezia - Church of the Frari - Monument of Doge Giovanni Pesaro

-

Ponti, Carlo (ca. 1860s) - Venezia - Ponte di RIalto

-

Ponti, Carlo (ca. 1860s-1870s) - Venezia - Torre dell'orologio. Albumen print

-

La porta del Palazzo ducale; Carlo Ponti

-

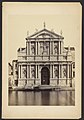

Carlo Ponti 1860–1870 Sainte Marie en Nazareth, vulgairement les Scalzi

-

Carlo Ponti (c.1865) Ponte dei Sospiri

-

Carlo Ponti Basilica SS. Giovanni e Paolo, Venice

-

Chiesa della Misericordia by Carlo Ponti

-

Carlo Ponti Palazzo Dario

-

Carlo Ponti (1862–65) Flower Seller, hand-coloured albumen print

-

A beggar, by Carlo Ponti, hand-coloured albumen print

-

Carlo Ponti Boy with tray around neck

-

Carlo Ponti, copy of Titian's Assunzione di Maria

-

Carlo Ponti copy of relief sculpture Riposo in Egitto

-

La porta del Palazzo ducale; Carlo Ponti

-

Carlo Ponti Trademark, print on card, reverse of photographic print

References[edit]

- ^ a b The History of the Discovery of Cinematography, Chapter Ten: 1860-1869

- ^ Plant, Margaret (2002-01-01). Venice: Fragile City, 1797-1997. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-08386-6.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k Paoli, Sylvia (2013). "Ponti, Carlo (c. 1822–1893) Optician and photographer". In Hannavy, John (ed.). Encyclopedia of Nineteenth-Century Photography. Routledge. pp. 1144–1146. ISBN 978-0-203-94178-2.

- ^ Becchetti, Piero (1978). Fotografi e fotografia in Italia 1839–1880 (in Italian). Rome: Quasar. pp. 124–125. ISBN 9788885020092.

- ^ Plant, Margaret (2002). Venice : fragile city : 1797-1997. Yale University Press. p. 128. ISBN 0-300-08386-6. OCLC 878568503.

- ^ a b Pelizzari, Maria Antonella (2011). Photography and Italy. London: Reaktion Books. pp. 49, 55–58. ISBN 978-1-86189-769-5. OCLC 587209562.

- ^ Buerger, Janet E. (March 1983). "Carlo Naya: Venetian Photographer: The Archaeology of Photography". Image. 26 (March 1983): 1.

- ^ Minici, Carlo Alberto Zotti (2001). Magic visions before the advent of the cinema (in Italian). Il poligrafo. ISBN 978-88-7115-299-8.

- ^ Ponti, Carlo (1862). The megalethoscope, invented by Charles Ponti, optician & photographer. : Its object and use. C. Ponti. OCLC 79947651.

- ^ Ponti Carlo. Charles Ponti Opticien Et Photographe De S.m. Le Roi D'italie : Inventeur Et Fabriquant De L'alethoscope ... : Place S.l Marc N. 52. Venise Riva Degli Schiavoni (Quai) N. 4180. C. Ponti 1862. Advertisement for Ponti's photographs of Venice and Italy. Wood-engraved ill. of the medal awarded Ponti at the London International Exhibition of 1862. Printed on gray wove paper

- ^ Verwiebe, Birgit (September 1995). "L'illusione nel tempo e nello spazio. Il megaletoscopio di Carlo Ponti, un apparecchio fotografi co degli anni 1860". Fotologia (in Italian). 16/17 (Autumn/Winter 1995): 53–61.

- ^ Heylen, Sylke; Maes, Herman (1999). "Megalethoscope Plates: A Case Study: Conservation Treatment of Megalethoscope plates from the Collection of the Museum for Art and History". Topics in Photographic Preservation. 8: 23–30.

- ^ Dune, Corinne (1 September 1996). "La photographie en spectacle : traitements de papiers albuminés peints transparents". Coré (in French). 1 (1996): 26–30. ISSN 1277-2550. OCLC 886969366.

- ^ Iglesias, Rodrigo Martín (2011). "A través de la pantalla". Jornadas Nacionales de Investigación en Arte en Argentina. VIII (2011). La Plata.

- ^ a b c Prandi, Alberto (1979). "Carlo Ponti". In Miraglia, Marina (ed.). Fotografia Italiana Dell'ottocento. Electa ; Alinari 1979 (Catalogue of the exhibition held in Florence, 1979 and in Venice, 1980) (in Italian). Alinari, Milano, Firenze: Electa. pp. 172–174. OCLC 6358323.

- ^ a b Schuller-Procopovici, Karin; de Dewitz, Bodo; Siegert, Dietmar, eds. (1994). Italien : Sehen Und Sterben : Photographien Zer Zeit Des Risorgimento (1845-1870) : Eine Ausstellung Des Agfa Foto-Historama : Römisch-Germanisches Museum Köln 23. September 1994-4. Dezember 1994 : Reiss-Museum Der Stadt Mannheim 2. März-5. Juni 1995. Braus 1994 (in German). Heidelberg: Braus. ISBN 9783894661014. OCLC 799565437.

- ^ Ponti, Carlo (1996). Un Magicien De L'image = Zauberkünstler Mit Bildern : Exposition Au Musée Suisse De L'appareil Photographique Du 31 Octobre 1996 Au 2 Février 1997 (in French). Vevey: Museée Musée suisse de l'appareil photographique. ISBN 9782970012801.

- ^ "The Megaletoscope of Carlo Ponti | Camera Museum". www.cameramuseum.ch. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ "Fotografie in Italien, 1846-1900, Sammlung Dietmar Siegert, Kunstwerke - Ernst von Siemens Kunststiftung". www.ernst-von-siemens-kunststiftung.de (in German). Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Loving, Charles L. (2002). Moriarty, Stephen Roger; O'Neil, Moira (eds.). A Gift of Light: Photographs in the Janos Scholz Collection. Indiana: University of Notre Dame Press. ISBN 0-268-0295-3-9.

- ^ "Carlo Ponti (The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection)". The J. Paul Getty Museum Collection. Retrieved 2023-02-23.

- ^ Musée d'Orsay. Heilbrun, Françoise (ed.). A History of Photography: The Musée D'Orsay Collection, 1839-1925. Norway: Flammarion. p. 57. ISBN 9782080300928.

- ^ "Carlo Ponti, Italian, ca. 1823–1893". Eastman Museum : Collection. Retrieved 23 February 2023.

- ^ "Archivio Carlo Montanaro – Cinema e Pre-cinema a Venezia e oltre…". Archivio Carlo Montanaro (in Italian). Retrieved 2023-02-23.