Biological ornament

A biological ornament is a characteristic of an animal that appears to serve a decorative function rather than a utilitarian function. Many are secondary sexual characteristics, and others appear on young birds during the period when they are dependent on being fed by their parents. Ornaments are used in displays to attract mates, which may lead to the evolutionary process known as sexual selection. An animal may shake, lengthen, or spread out its ornament in order to get the attention of the opposite sex, which will in turn choose the most attractive one with which to mate. Ornaments are most often observed in males, and choosing an extravagantly ornamented male benefits females as the genes that produce the ornament will be passed on to her offspring, increasing their own reproductive fitness. As Ronald Fisher noted, the male offspring will inherit the ornament while the female offspring will inherit the preference for said ornament, which can lead to a positive feedback loop known as a Fisherian runaway. These structures serve as cues to animal sexual behaviour, that is, they are sensory signals that affect mating responses. Therefore, ornamental traits are often selected by mate choice.[1]

Sexual selection

[edit]There are several evolutionary explanations for the presence of ornaments. Darwin was the first to correctly hypothesize that sexual selection by female choice was responsible for the evolution of elaborate plumage and remarkable displays in male birds such as the quetzal and the sage grouse.[2] Sexual selection is selection acting on variation among individuals in their ability to obtain access to mating partners.[3] In his 1871 book The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex, Darwin was perplexed by the elaborate ornamentation that males of some species have because they appeared to be detrimental to survival and have negative consequences for reproductive success. Darwin proposed two explanations for the existence of such traits: these traits are useful in male-male combat or they are preferred by females.[2]

More recently, many alternative theories of sexual selection have been proposed, many of them centered around the idea that elaborate male ornaments allow females to assess the 'quality' of a male's genes so that she can ensure that her offspring get the best genes (health, physical vigor, etc.). In 1975, Amotz Zahavi proposed the handicap principle, which is the idea that elaborate male ornaments are actually a handicap and that males with such ornaments are demonstrating their physical quality by showing that they can survive despite having such a handicap.[4] Potential mates know that the ornament indicates quality because inferior mates could not afford to produce such wastefully extravagant ornaments. More specifically, ornaments may indicate the underlying genetic quality of the male, for example, in peafowls their tail size and symmetry is largely dictated by genetics.[5] In other words, each peafowl grows the best tail they are able to and only those with the highest genetic quality can produce the most impressive tails.[6] The tail of a peafowl is an honest signal for the female in determining the health status of a potential mate.[7]

In 1982, William Hamilton and Merlene Zuk proposed that male ornaments may enable healthy males to advertise the fact that they are free of diseases and parasites, a theory that is now known as the "Bright Male" hypothesis.[8] According to this hypothesis, if an animal was diseased, it would not be able to grow such beautifully colored plumage. Since disease is a major source of juvenile mortality, females would choose the males with the most elaborate ornaments to ensure that they will have healthy offspring.

Honest signalling

[edit]Females may improve survival of offspring by selecting mates on the basis of ornamentation signals that honestly reveal health. Numerous studies have been carried out to test if sexual selection based on the intensity of the expression of ornamentation in males reflects their level of oxidative stress.[9][10] It is considered that female choice may select for traits in males that reliably indicate level of oxidative stress, as such traits would be a good indicator of male quality[9][10] Elevated oxidative stress can lead to increased DNA damage that can contribute to aging or cancer. Female choice thus may promote the evolution of ornaments in males that reliably reveal the level of oxidative stress in potential mating partners.

Examples

[edit]

Ornamentation is a common biological trait seen in birds. The male quetzal has elaborate ornamentation to aid in mating. Male quetzals have iridescent green wing coverts, back, chest and head, and a red belly. During mating season, male quetzals grow twin tail feathers that form an amazing train up to three feet long (one meter) with vibrant colors.[11] Most female quetzals have no ornamentation and are drab. Coloration and tail feather length in quetzals help determine mate choice because the females choose the more elaborately ornamented males.[12]

Other birds that exhibit ornamentation include sage grouses and widowbirds. Sage grouse birds gather in a lek, or a special display area, and strut and display their plumage to attract a mate.[13] Whereas, the extraordinary tail feathers of the male long-tailed widowbird are displayed to choosy females while the male flies above his grassland territory.[12]

Biological ornamentation is also seen in the common roach fish, Rutilus rutilus. Male roach develop sexual ornaments (breeding tubercles) during the breeding season.[14] Roach display lek-like spawning behavior, whereby females choose between males, usually choosing the more elaborately ornamented ones.

Alternate functions

[edit]

Lures

[edit]There are many instances in which decorations may appear ornamental but actually serve other functions. For example, some species of spiders decorate their webs with shimmering ornaments in order to lure prey.[15] Orb-weaver spiders use elaborate, ultraviolet coloured web ornaments to attract bees that specialize in taking nectar from similarly coloured flowers. In turn, the spider captures the bee in its nest and reaps the food benefits. In this case, what may seem as an ornament to attract mates is actually used as a lure to trap food.

Armaments

[edit]Armaments are anatomical weapons which have evolved amongst species whose males compete intra-sexually for access to females. Armaments are used in direct contests for the opportunity to mate or for the resources needed to attract mates. These weapons such as tusks, antlers, horns, spurs, and lips increase success in rivalry among competitors to gain or maintain dominance, control a harem, or obtain access to territories Examples of animals that use armaments to compete in battle against rival males include deer and antelope; scarabid, lucanid, and cerambycid beetles; certain fish, and narwhales.[16] A buck in peak physical health will shed his antlers later than a weaker buck.[17] Antlers harden just before the breeding season and drop off afterward, and they only occur in males (except in caribou). Antlers are used extensively for fighting and ritualized antler to antler shoving matches.[18]

Use in courtship displays

[edit]

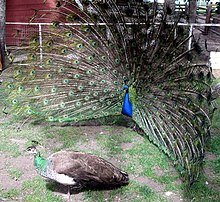

Biological ornaments are used in courtship displays in many species, especially insects, fish, and birds. A well known ornament used in courting displays is seen in peafowls. Male peacocks spread and shake their tails to attract and impress potential mates. Peahens choose the peacocks with the largest number of eyespots on their tails,[19] because only the healthiest peacocks can afford to divert energy and nutrients towards growing expensive and cumbersome plumage,[20] as explained by the handicap principle. More elaborate ornamentation increases the likelihood that a male will mate and has been shown to affect survival of their offspring.[19] The offspring of males with larger eyespots on their ornamented tails have been shown to weigh more and were more likely to be alive after 2 years than the progeny of males with fewer eyespots.[19]

Ornaments that play a role in reproduction develop under the influence of two series of genes.[21] First, it develops from genes in males that determine the presence and characteristics of the ornament, and second it develops from genes in females that draw her to this kind of ornamentation.[18] Important studies concerning this have been conducted in the Stalk-eyed fly, showing that females are attracted to mates that share characteristics with their fathers. Therefore, sexual selection is a mechanism that differently affects both sexes. Initially, an ornament may have been selected for reasons not linked to reproduction, but over time, the characteristic may become exaggerated due to sexual selection.[18] The females will select for more and more elaborate ornamentation, which represents better survival skills because the male with those characteristics must be physically fit enough to handle the unwanted predator attention that comes with the ornament.[18] Therefore, the males with the most extreme ornamentation will have more offspring, and the gene for "showiness" will be passed on. This evolution can then lead to organs of excessive size that may become troublesome for the males, such as large, bushy tails, bright feathers, etc.[18] The point of equilibrium is reached when their ornamentation becomes too much of a handicap on the male's survival, and the "vital" natural selection goes to work, altering the exaggerated characteristic until it reaches an equilibrium point.[18]

Sexually selected ornaments of males may impose survival costs but advance success in the competition for mates.[19] The interesting thing about sexual ornaments is that they impede the male's chances for survival, yet they continue to be passed on from generation to generation. The larger the male peacock's tail feathers are, or the brighter the birds feathers are, the harder it is for them to escape predators and maneuver through trees, and the more food they will need to eat to develop the ornament. A peacock's tail almost certainly reduces survival of the peacock as they reduce maneuverability, power of flight, and make the bird more conspicuous to predators.[1] Ornaments, therefore, have a great effect on the fitness of the animals that carry them, but the benefits of having an ornament must outweigh the costs for them to be passed on.

Parental favoritism in nestlings

[edit]

Biological ornamentation has been shown to affect parental favoritism in nestlings. This can be observed several species of water birds.[22] For example, baby American coots hatch out with long, orange-tipped plumes on their backs and throats which provide signals to parents used to determine which individuals to feed preferentially.[19] In experiments in which ornaments have been physically altered on baby coots, elaborate ornamentation has been proven to be beneficial to young offspring.[19] Ornamented individuals received more frequent feedings from parents. Therefore, the relative growth rates of ornamented chicks were much higher compared with the experimentally altered chicks.[19]

Female ornamentation

[edit]Male animals are typically more elaborately ornamented than females.[23] The classic sexual selection theory notes that because sperm are cheaper to produce than eggs, and because males generally compete more intensely for reproductive opportunities and invest less in parental care than females, males can obtain greater fitness benefits from mating multiple times.[24] Therefore, sexual selection typically results in male-biased sex differences in secondary sexual characteristics, which are non-reproductive body parts that help distinguish between sexes in a species.[24]

Female ornamentation has long been overlooked because of the greater prevalence of elaborate displays in males.[24] However, the circumstances under which females would benefit from honestly signaling their quality are limited.[24] Females are not expected to invest in ornamentation unless the fitness benefits of the ornament exceed those from investing the resources directly into offspring.[24] An example of a scenario in which female ornamentation occurs is in the pipefish. Within this species of fish, sex roles are reversed so the male is responsible for the postzygotic care. Accordingly, females must compete for access to male parental care. Thus, females have been selected for ornamentation as the benefit of producing the ornamentation, namely male paternal care, outweighs the costs, such as the energy requirements. Most notably, their venter becomes more colourful during breeding season. Males tend to prefer females with more colourful venters, with research showing that there is a positive association between this ornament and the condition of the female. As this ornamentation reliably indicates mate quality, it can be considered an honest signal.[25] In the phalaropes and the Eurasian dotterel, females are more brightly colored than males, and it is the males who are primarily responsible for parental care.

It has been proposed that when females gain direct benefits from mating, females may instead be selected for ornamentation that deceives males about their reproductive state.[24] In empidid dance flies, males frequently provide nuptial gifts and it is usually to only the female that is ornamented.[24] Female traits in empidids, such as abdominal sacs and enlarged pinnate leg scales, have been suggested to 'deceive' males into matings by disguising egg maturity.[24]

References and notes

[edit]- ^ a b van Dijk, D; Sloot, P.M.A.; Tay, J.C.; Schut, M.C. (May 2010). "Individual-based simulation of sexual selection: A quantitative genetic approach" (PDF). Procedia Computer Science. 1 (1): 2003–2011. doi:10.1016/j.procs.2010.04.224.

- ^ a b Darwin, C., ed. (1871). The Descent of Man. Prometheus Books.

- ^ Kappeler, P., ed. (2010). Animal Behavior: Evolution and Mechanisms. Springer.

- ^ Zahavi, A. (1975). "Mate selection - a selection for a handicap" (PDF). Journal of Theoretical Biology. 53 (1): 205–214. Bibcode:1975JThBi..53..205Z. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.586.3819. doi:10.1016/0022-5193(75)90111-3. PMID 1195756.

- ^ Møller A. P. (1990). "Fluctuating asymmetry in male sexual ornaments may reliably reveal male quality". Animal Behaviour. 40 (6): 1185–1187. doi:10.1016/S0003-3472(05)80187-3. S2CID 53149623.

- ^ Sundie J. M.; Kenrick D. T.; Griskevicius V.; Tybur J. M.; Vohs K. D.; Beal D. J. (2011). "Peacocks, Porsches, and Thorstein Veblen: conspicuous consumption as a sexual signaling system". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 100 (4): 664–680. doi:10.1037/a0021669. PMID 21038972.

- ^ Loyau, Adeline; Jalme, Michel Saint; Cagniant, Cécile; Sorci, Gabriele (2005-05-03). "Multiple sexual advertisements honestly reflect health status in peacocks (Pavo cristatus)". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 58 (6): 552–557. doi:10.1007/s00265-005-0958-y. ISSN 0340-5443. S2CID 27621492.

- ^ Hamilton, W. D. & M. Zuk. (1982). "Heritable true fitness and bright birds: A role for parasites?" (PDF). Science. 218 (4570): 384–387. Bibcode:1982Sci...218..384H. doi:10.1126/science.7123238. PMID 7123238.

- ^ a b von Schantz, T.; Bensch, S.; Grahn, M.; Hasselquist, D.; Wittzell, H. (1999). "Good genes, oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 266 (1414): 1–12. doi:10.1098/rspb.1999.0597. PMC 1689644. PMID 10081154.

- ^ a b Garratt, M.; Brooks, R. C. (2012). "Oxidative stress and condition-dependent sexual signals: More than just seeing red". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 279 (1741): 3121–3130. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0568. PMC 3385731. PMID 22648155.

- ^ Lebbin, D. J. (2007). "Nesting Behavior and Nestling Care of the Pavonine Quetzal (Pharomachrus pavoninus)". The Wilson Journal of Ornithology. 119 (3): 458–463. doi:10.1676/06-138.1. JSTOR 20456032. S2CID 85749023.

- ^ a b Alcock, J., ed. (2005). Animal Behavior (8th ed.). Sinauer Associates. [page needed]

- ^ Gibson R.M. & J. W. Bradbury (1985). "Sexual selection in lekking sage grouse: phenotypic correlates of male mating success". Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology. 18 (2): 117–123. doi:10.1007/bf00299040. JSTOR 4599870. S2CID 33338688.

- ^ Taskinen, J. & R. Kortet. (2002). "Dead and alive parasites: sexual ornaments signal resistance in the male fish, Rutilus rutilus". Evolutionary Ecology Research. 4: 919–929.

- ^ Chenga, R.C. & I.-Min Tso. (2007). "Signaling by decorating webs: luring prey or deterring predators?". Behavioral Ecology. 18 (6): 1085–1091. doi:10.1093/beheco/arm081.

- ^ ) Stearns, Stephen C., and Rolf F. Hoekstra. Evolution: an Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2005.

- ^ Robb, Bob. “Why Do Deer Shed Their Antlers?” Grand View Outdoors, 4 June 2015, www.grandviewoutdoors.com/big-game-hunting/why-do-deer-shed-their-antlers/.

- ^ a b c d e f Goss, R.J., ed. (1983). Deer antlers: Regeneration, function, and evolution. Academic Press.

- ^ a b c d e f g Alcock, J., ed. (1997). Animal Behavior: an Evolutionary Approach (6th ed.). Sinauer Associates. ISBN 9780878930098.

- ^ Pinker, S., ed. (2002). Animal Behavior: an Evolutionary Approach. Penguin. [dubious – discuss]

- ^ Panafieu, J., ed. (2007). Evolution. Seven Stories.

- ^ Krebs, Elizabeth A.; Putland, David A. (2004), "Chic chicks: the evolution of chick ornamentation in rails", Behavioral Ecology, 15 (6): 946–951, doi:10.1093/beheco/arh078

- ^ Rubenstein, D. & I. Lovette. (2009). "Reproductive Skew and Selection on Female Ornamentation in Social Species". Nature. 462 (7274): 786–789. Bibcode:2009Natur.462..786R. doi:10.1038/nature08614. PMID 20010686. S2CID 4373305.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Lebas, Natasha R.; Hockham, Leon R.; Ritchie, Michael G. (2003). "Nonlinear and correlational sexual selection on 'honest' female ornamentation". Proceedings of the Royal Society of London. Series B: Biological Sciences. 270 (1529): 2159–2165. doi:10.1098/rspb.2003.2482. PMC 1691484. PMID 14561280.

- ^ Thornhill, Randy; Gangestad, Steven W. (2008). The evolutionary biology of human female sexuality. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 79. ISBN 978-0-19-534098-3.